1. Background

Streptococcus Pneumonia is the major cause of community-acquired pneumonia and meningitis (1) which may affect patients in all age groups, particularly those underlying medical conditions (1). The emergence of Penicillin resistance and multidrug-resistant in pneumococcal strains has become a global concern. Since late 1980s, antibiotic-resistant Pneumococcisp. has been markedly increased worldwide and is recognized as globally spread pathogens (2). Traditionally, laboratories screened clinically significant isolates of S. Pneumonia to evaluate the Penicillin resistance with a 1-mg oxacillin disk (3). Several reports have demonstrated a correlation between increased MICs of Penicillin and increased MICs of Cephalosporins and other β-lactam antibiotics (4-6), showing that pneumococcal resistance to Penicillin may predict an unfavorable response to other antibiotics (2).

Penicillin-resistant Pneumococci is particularly common in Europe, South Africa, Latin America and United States (7-9), and the prevalence have been increased through the time. For instance, in the United States, resistance to Penicillin was 5% before 1989 (including 0.02% of isolates for which MICs were 2.0 mg/mL). However, this amount was 6.6% in 1991-1992, 9.5% in 1994-1995, 21.5% in 1999-2000, and decreased to 14.6% in 2004-2005, after introduction of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (10-12). Resistant Pneumococci may spread from one country to another hence widened and intensified surveillance is needed in all areas, especially in countries where resistance is relatively uncommon (13, 14). Given the significant rate of Penicillin resistance, broad spectrum Cephalosporins (especially Ceftriaxone) are the proper choices for pneumococcal infections (15-17). All in all, there are studies reporting the increase in Ceftriaxone resistance among pneumococcal isolates (18-20), it is important to monitor the changing pattern and prevalence of antibiotic resistance in order to provide reliable information to refer to in empirical treatments of clinical infections.

2. Objectives

To consider the Ceftriaxone pneumococcal resistance pattern, one of the most prescribed antimicrobial agents in our region, microbiological survey was performed on pneumococcal strains during a two-year period. This study investigated the in vitro activities of isolated organisms, using E-test.

3. Patients and Methods

In the present study, 35 strains of Pneumococci were isolated from blood samples of 35 different patients admitted to two educational hospitals in Mashhad, North East of Iran. Minimal inhibitory concentration to Ceftriaxone determined, using E-test method based on the manufacturer instructions. Interpretation of the results was carried out according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) definitions (21). According to the CLSI definition for non-meningeal isolates, a microorganism is considered as a susceptible isolated if MIC ≤ 1µg/mL, intermediately resistant if MIC = 2µg/mL, and resistant if MIC ≥ 4µg/mL.

4. Results

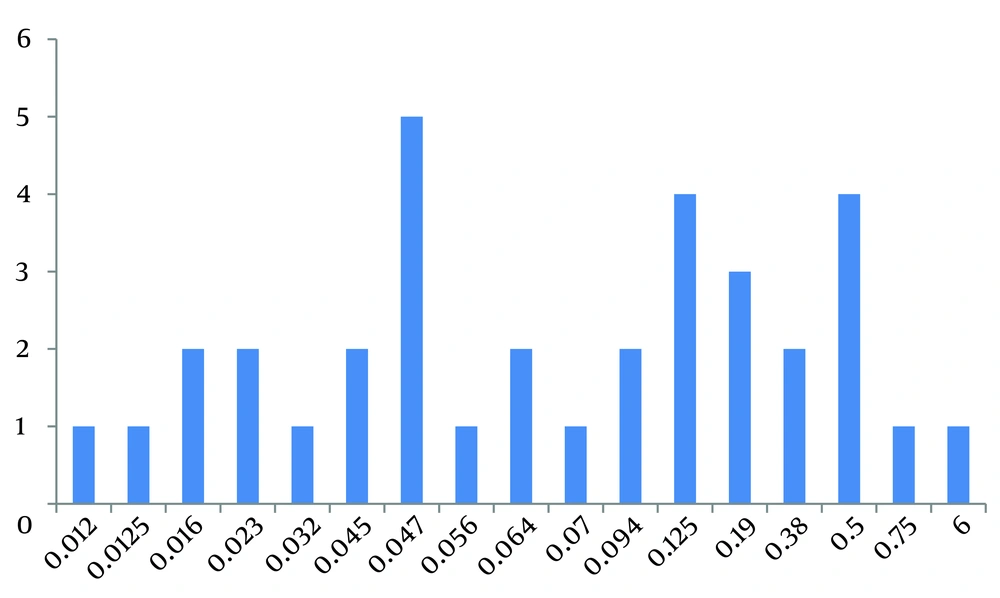

Amongst 35 clinical isolates evaluated in this study, based on CLSI guidelines, only one isolate (2.86%) was resistant to Ceftriaxone (MIC > 1) and 34 isolates (97.14%) were sensitive to this antibiotic (Figure 1).

5. Discussion

As reported in many studies, there is a high frequency of Penicillin resistance among pneumococcal isolates, but the resistance to Ceftriaxone is variable. There are some studies in which the trends of Ceftriaxone susceptibility have been evaluated. In a ten-year study (1998 - 2007) conducted in Calgary, Canada, 1.7% of 1170 pneumococcal isolates were resistant to Ceftriaxone (22). Despite low level of resistance in previous study, in a retrospective study in a university hospital in Taiwan (2000 - 2007), 18.4% of non-meningeal and 34.9% of meningeal isolates (a total number of 3729 isolates) were not susceptible to Ceftriaxone (23). Moreover, in a study conducted in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, from February 2000 and November 2001, including 78 isolates of S. Pneumonia from different samples (blood, cerebrospinal fluid, bone, and peritoneal fluid) only 1.28% of isolates were resistant to Ceftriaxone (24) although authors suggested Ceftriaxone for treating invasive pneumococcal infections other than the central nervous system infections (25). A large study included 1,000 clinical isolates of S pneumonia, collected by U.S. laboratories in 2001-2002 showed that nearly 2% of isolates were resistant to Ceftriaxone (26). The rate of resistance to Ceftriaxone in our study was similar to the other studies (2.86%).

It is noticeable that studies on pediatric patients' samples, revealed higher rates of resistance, it showed that 35% of S. Pneumonia isolated from nasopharyngeal swabs of children from Darwin, Australia, and 24.7% of S. Pneumonia isolated from hypopharynx aspirate specimens collected from children admitted to 4 Children’s hospital in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, China were resistant to Ceftriaxone (27, 28). Another study on 46 strains of S. Pneumonia isolated from children with different infections referred to an emergency ward of a pediatric hospital in Rumania, during January 2001 - September 2002, revealed 26.09% resistance to Ceftriaxone (29). In a study which was conducted in Isfahan, Iran 98 pneumococcal isolates obtained from pediatric patients aged 5 - 10 years old, 89.1% and 81.5% of non-meningeal and meningeal isolates were susceptible to Ceftriaxone. MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.25 and 1.5, respectively; thus the authors suggested to administer Ceftriaxone in suspected cases of pneumococcal infection (30, 31).

Considering the low rates of Ceftriaxone resistance amongst isolated Pneumococci in this study, administering of Ceftriaxone alone for the treatment of adult patients with invasive pneumococcal infections (other than CNS infections) is effective; but pediatric patients and patients with CNS infections should be treated with Ceftriaxone and Vancomycin. It appears that the diminution in Vancomycin use has been resulted in decreased resistance rate of other bacteria which are sensitive to these antimicrobial agents (such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococci).