1. Background

Candida spp. are members of a genus, including closely related fungal species, such as Candida albicans (C. albicans), C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, and in addition, distantly related organisms including C. glabrata and C. krusei (1, 2). Candida spp. are among common causative agents of nosocomial infections in the United States, Europe and other parts of the world (3). Candida albicans remains the predominant species in related infections, although recent studies suggest an increase in the proportion of species other than C. albicans, such as C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis and C. krusei (4, 5). Candida spp. commonly colonize the gut, oral and vaginal cavity in healthy individuals. However, they are also capable of causing disease under circumstances that prosper their overgrowth and damage of the host (6). The range of diseases caused by the species varies from superficial and benign infections of the mucosae, such as oropharyngeal or vulvovaginal candidiasis, to severe life-threatening conditions of disseminated or invasive candidiasis; especially in immune-compromised patients (7-10). The most important factors predisposing individuals to mucosal related infections include Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, diabetes, antibiotic consumption and use of immunosuppressive drugs and extremes of age (11-13). Vulvovaginal candidiasis is common in certain conditions, even in otherwise healthy females (14). Risk factors for UTIs include female gender, age of 65 years or older, deficiency of immune system, and urinary catheters (15). Although candiduria is often associated with a benign outcome (16), several large studies of hospitalized patients have demonstrated decreased survival of patients with candiduria in comparison with respective control populations (17, 18). Candiduria leads to systemic infection or candidemia only in 0 - 8% of the cases (19-21). Therefore, it remains unclear if candiduria leads directly to mortality or alternatively merely constitutes a surrogate marker.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was the assessment of prevalence of candiduria and vulvovaginitis candidiasis among patients attending a referral laboratory in Neyshabur during 2013 - 2015.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients and Collection of Fungal Species

This cross-sectional epidemiologic study was carried out in Neyshabur and countryside rural areas between 2013 and 2015 to determine the prevalence of candiduria in Neyshabur district. A total of 421 vulvovaginitis samples were collected in this study. Patients of all ages, all ethnicities and from both rural and urban areas were included. Patients from other cities were excluded. Moreover, Candida spp. from other infection sites other than UTI were excluded.

Samples were collected from patients complaining of urinary tract pains, dysuria or discharge and pus secretions.

3.2. Identification Procedures

Briefly, 10 μL of each un-centrifuged sample was cultured on CHROM agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 hours, aerobically. Candida species were identified based on colony morphology on CHROM agar (CHROM agar Candida®, France), germ tube production and micro-morphology on corn meal agar including 1% Tween 80.

The materials and methods were tested for quality and confirmation was achieved with the following approaches: the micro tubes had been sterile, samplers had been calibrated, the CHROM agar medium was prepared from a valid corporation, and the culture of samples was conducted under sterile conditions and using 70% ethanol for disinfection. Furthermore, a valid microscope was employed for morphology diagnosis.

Support for this study was obtained from the research and technology deputy of ACECR, Mashhad Branch.

Several variables were assessed such as age, gender, years and months and living in rural or urban places. These criteria were considered in some previous published studies found in our literature search (22-24). However, some of variables may not specifically or certainly be related to the predisposition of candiduria.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with the SPSS software version 20 (IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 20, Armonk, NY, IBM Corp.), using the chi-square and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. T- and F-tests were employed when needed (between two groups or amongst more, respectively).

3.4. Ethical Approval

This work was supported by ACECR and ethical approval was provided by this center.

The patients provided consent for this study, and no animal model was examined here.

4. Results

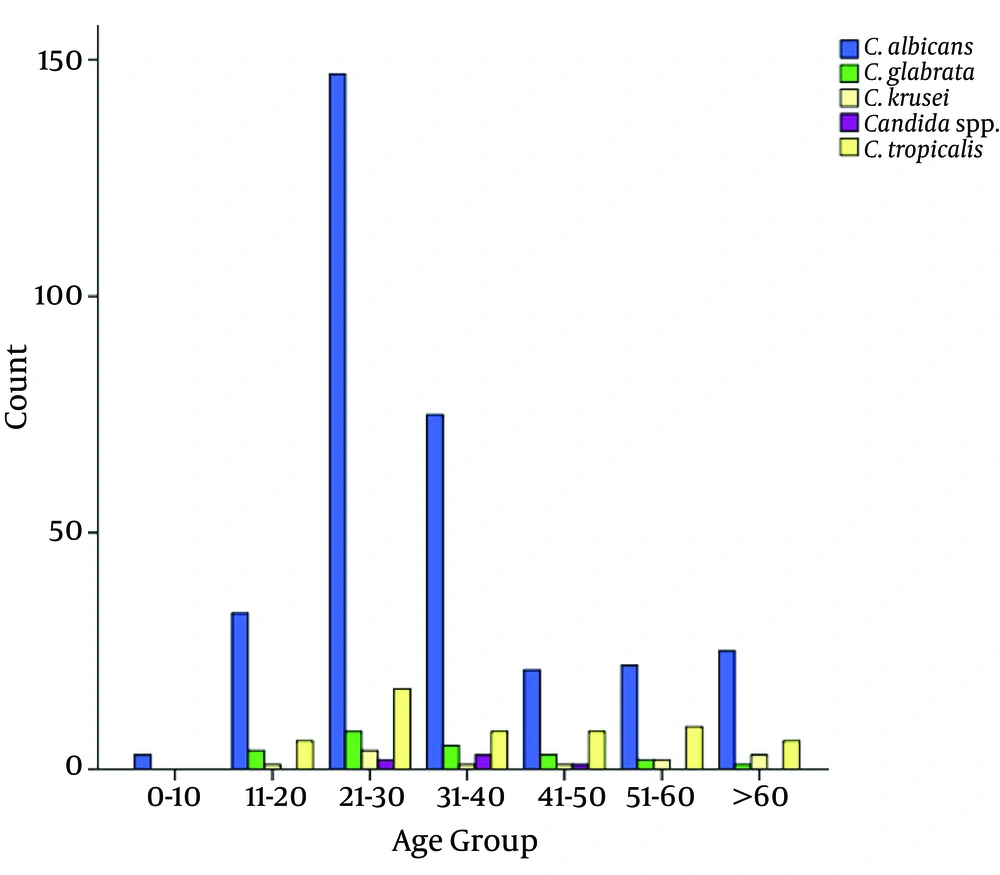

The mean age of the patients was 34.7 ± 16.3. From Table 1 and Figure 1, it is obvious that C. albicans was the predominant species isolated. Moreover, age groups of 21 to 30 and 0 to 1 years were the most and the least infected individuals. Moreover, Candida spp. were significantly more common in female than male patients (P value < 0.001, Table 2).

| C. albicans | C. glabrata | C. krusei | C. spp. | C. tropicalis | Total | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| 0 - 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.12 |

| 11 - 20 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 44 | 0.001 |

| 21 - 30 | 147 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 17 | 178 | 0.001 |

| 31 - 40 | 75 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 92 | < 0.001 |

| 41 - 50 | 21 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 34 | 0.033 |

| 51 - 60 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 35 | 0.012 |

| > 60 | 25 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 35 | 0.003 |

| Total | 326 (77.4) | 23 (5.46) | 12 (2.85) | 6 (1.42) | 54 (12.8) | 421 (100) |

The Prevalence of Candida spp. Among Various Age Groups

| C. albicans | C. glabrata | C. krusei | C. spp | C. tropicalis | Odds ratio | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 321 | 23 | 12 | 6 | 51 | 4.46 | 413 | < 0.0001 |

| Male | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.33 | 8 | |

| Total | 326 (77.4) | 23 (5.46) | 12 (2.85) | 6 (1.42) | 54 (12.8) | 421 (100) |

The Candida spp. Distribution Between Male and Female Patients

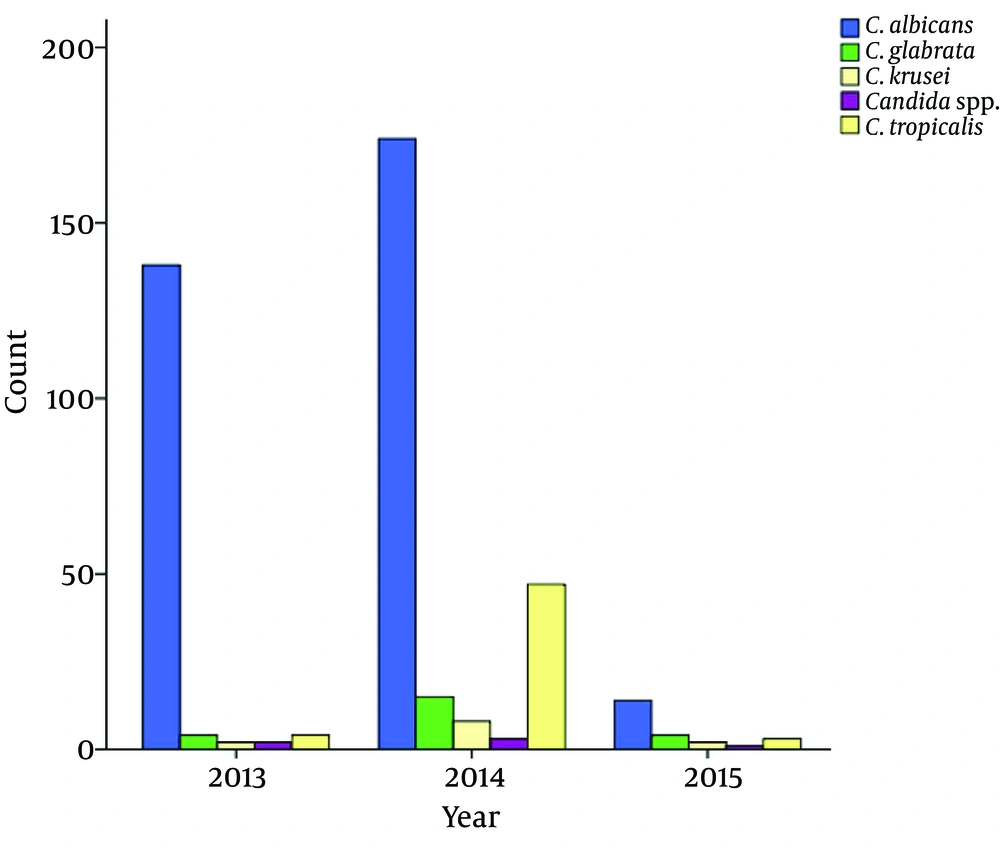

It was demonstrated that the prevalence of C. albicans was significantly declined from 2013-2014 to 2015. Furthermore, the prevalence of C. tropicalis was significantly higher in 2014 compared to 2013 and 2015 (Table 3 and Figure 2). Fifteen patients showed mixed infection of C. albicans, E. coli and Enterobacter aerogenes isolates. Moreover, all species had a colony count of > 103 (Table 4).

| Year | C. albicans | C. glabrata | C. krusei | Candida spp. | C. tropicalis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 138 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 150 |

| 2014 | 174 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 47 | 247 |

| 2015 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 24 |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.276 | 0.412 | 0.0012 | 0.044 |

| Total | 326 (77.4) | 23 (5.46) | 12 (2.85) | 6 (1.42) | 54 (12.8) | 421 (100) |

The Incidence of Candida spp. According to Year

| Colony Count (CFU) | < 1000 | 1001 - 5000 | 5001 - 10000 | > 10000 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 59 | 39 | 79 | 149 | 326 (77.4) |

| C. glabrata | 2 | 9 | 1 | 11 | 23 (5.46) |

| C. krusei | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 12 (2.85) |

| C.spp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 (1.42) |

| C. tropicalis | 9 | 1 | 18 | 26 | 54 (12.8) |

| Total (%) | 73 (17.3) | 52 (12.4) | 98 (23.3) | 198 (47) | 421 (100) |

The Colony Counts of Candida spp. and the Prevalence in Each Count

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study assessing the prevalence of Candida spp. in patients from Neyshabur, North-east of Iran. In the current study, the mean age of patients was 34.7 ± 16.3. From Table 1 and Figure 1, it is obvious that C. albicans was the predominant species isolated. This result is similar to a study from south of Iran, in which C. albicans was predominant (48%) followed by C. krusei (16.1%), C. glabrata (13.5%), C. kefyr (7.4%), C. parapsilosis (4.8%), C. tropicalis (1.7%) and other species (8.5%) (25). Moreover, age groups of 21 to 30 and 0 to 1 years were the most and the least infected individuals. One of reasons for more urethral infection among young adults compared to children and other ages, may be because of higher sexual activities. Moreover, Candida spp. exhibited significantly higher rates amongst female than male patients (P value < 0.001), indicating the greater vulnerability of females to candida UTI. In this study, C. albicans was the most common species (77.4%) followed by C. tropicalis (12.8%), C. glabrata (5.46%), C. krusei (2.85%) and other candida spp. (1.42%) remaining unspecified. In agreement with our results, a study by Shokohi showed that C. albicans was the predominant species (77.5%), followed by C. glabrata (15%), C. tropicalis (5%) and C. krusei (2.5%) by Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) (26). In another study by Zarei Mahmoudabadi, the prevalence of Candida spp. among 300 females was determined as 49%. On the other hand, recurrent and acute vaginal candidiasis was 48.3% and 51.7%, respectively. In addition, C. albicans was the most prevalent species among the isolates followed by C. glabrata, C. dubliniensis and other Candida species (27). Rad’s study demonstrated that C. albicans was the most common (67%) species amongst single and mixed infections and other identified species included: C. glabrata (18.3%) followed by C. tropicalis (6.8%), C. krusei (5.8%), C. parapsilosis (1.6%) and C. guilliermondii (0.5%) (28). These studies revealed that C. albicans is the most common candida in vulvovaginitis. In another study, it was confirmed that C. albicans and C. glabrata were the predominant species isolated from the specimens. However, the difference amongst previous studies and the present study includes epidemiological differences, different years on which the study was conducted, different sample sizes and sources of infections, ages and gender of patients.

The mixed infection of C. albicans and C. glabrata was demonstrated among 29 patients, while mixed infection of C. albicans, Escherichia coli and Enterobacter aerogenes isolates was observed among 15 patients. In a study by Mohammadi, a mix of C. glabrata and C. albicans was the most usual mixed infection from a total of 855 yeast strains isolated from different clinical specimens (29).

It was demonstrated that the prevalence of C. albicans has significantly declined from 2013-2014 to 2015. Furthermore, the prevalence of C. tropicalis was significantly higher in 2014 compared to 2013 and 2015. Moreover, all the species had a colony count of > 103. The weak points of the current study were lack of molecular method for the identification of species, narrow area of study, lack of antibiotic susceptibility test of species, and vagueness in the education level and economic status of patients. The strong points include the relatively high number of isolates collected from the study area for three years.

In this study, the most common mixed infection was the combination of C. albicans and C. glabrata. Individuals, who were sexually active and those with urogenital sex were more likely to have recurrent vulvovaginal and urethral candidiasis.

5.1. Conclusion

In this study, C. albicans was the most common species isolated from vulvovaginitis and urethral infection. The prevalence of Candida spp. was significantly declined from 2013 to 2015. Moreover, the Candida spp. counts were mostly higher than 103cfu/mL. The mixed infection of C. albicans, C. glabrata, Escherichia coli and E. aerogenes was observed among several patients.