1. Background

Listeria monocytogenes, a bacterium that causes foodborne infections, can result in abortion and diseases as severe as encephalomeningitis, septicemias and gastroenteritis. It is a facultative intracellular and Gram-positive bacterium, presented in pregnant women by flu-like symptoms (1-3). Along with the occurrence of listeriosis in adults, it is especially important in fetuses, since around 40% of all cases are pregnancy-related, where the disease can cause miscarriage, premature birth, stillbirth, and neonatal disease (2, 4). The incidence of listeriosis among pregnant women is 17 times as high as the general population (12 per 100000 vs. 0.7 per 100000, respectively) (5).

L. monocytogenes has six basic virulence genes including prfA, plcA, hlyA, mpl, actA, and plcB, located together in one virulence gene cluster between the house keeping genes idh and prs (6). L. monocytogenes is identified by selective enrichments and biochemical analyses. One of the best instruments that has a tremendous potential for detection of foodborne pathogens is polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and therefore it has been one of the most sought-after methods in food microbiology in recent years(7-9).

2. Objectives

The objective of the present study was detecting the virulence-associated gene(s) in L. monocytogenes by PCR and culture methods among women with abortion. Finally, we compared the two results.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Samples Collection

In this pilot and cross-sectional study, a total of 96 samples including vaginal swabs were collected by convenience samplings method from patients with spontaneous abortions who had been admitted to educational medical centers of Tehran, Iran, during June 2012 to May 2013. All the specimens were transferred on ice to the Microbiology Research Laboratory of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria was the swab of a sample of abortion under 20 weeks of pregnancy, and exclusion criteria was the swab of a sample of pregnancy tissues more than 20 weeks of pregnancy.

3.3. Enrichment, Culturing, and Morphological and Biochemical Identification

Briefly, the vaginal swabs were placed in 10 mL tryptic soy broth with yeast extract (TSBYE); the samples were incubated at 4°C. After a one-week period or a one to three month period of incubation, aliquots from the enrichment broth (TSBYE) were streaked onto PALCAM agar (Merck, Germany) and blood agar (Merck, Germany) and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 hours. Green shiny colonies with diffused black shadows around them on PALCAM agar and yellow small colonies with ß-hemolysis on blood agar were suspected to be Listeria. The isolates were confirmed by Gram staining, catalase reaction, oxidase test, tumbling motility at 20-25ºC, methyl red-Voges Proskauer (MR-VP) tests, and fermentation of sugars (xylose, rhamnose and mannitol). All the biochemically characterized isolates were tested for haemolysis on sheep blood agar.

3.4. DNA Extraction

DNA extraction was performed by AccuPrepgenomic DNA extraction kit (Bioneer Co., Korea). After one week, the vaginal swab specimens with TSBYE were incubated at 4°C; then 20 μL of proteinase K and 200 μL of binding buffer were added to 200 μL of samples; after mixing, they were incubated at 60°C for 20 minutes; 100 μL of isopropanol was added to the mixtures. The lysates were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for one minute; washing buffer one and then two were added to the tubes, respectively. After the centrifuge, 200 μL of the elution buffers were added and the final mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for one minute. The eluted genomic DNA was stored at -20°C for further analyses.

3.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction

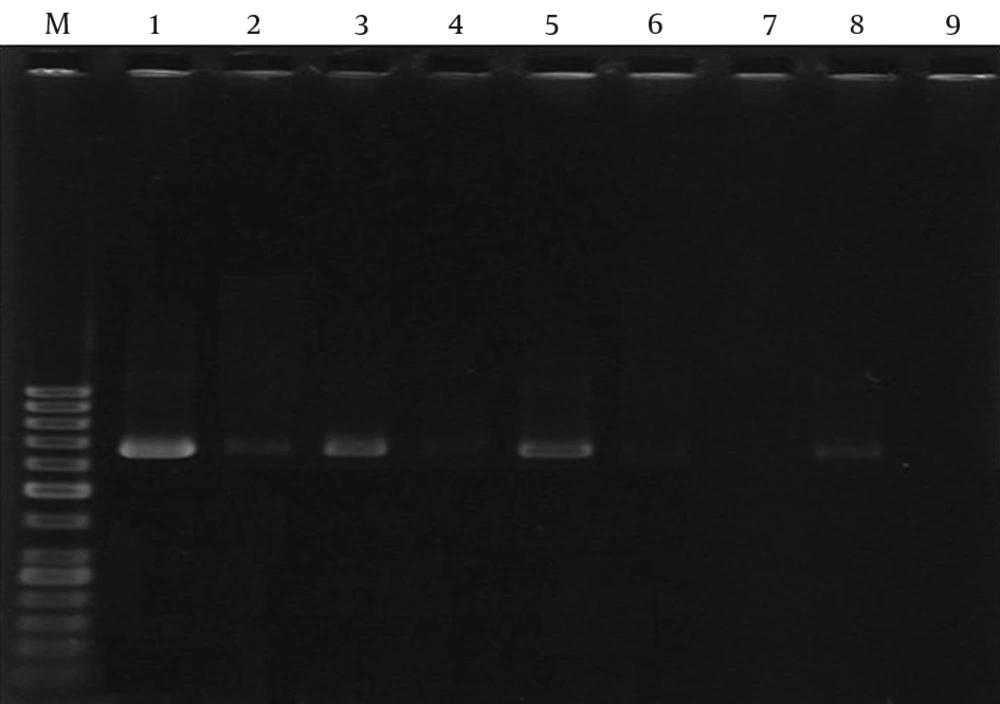

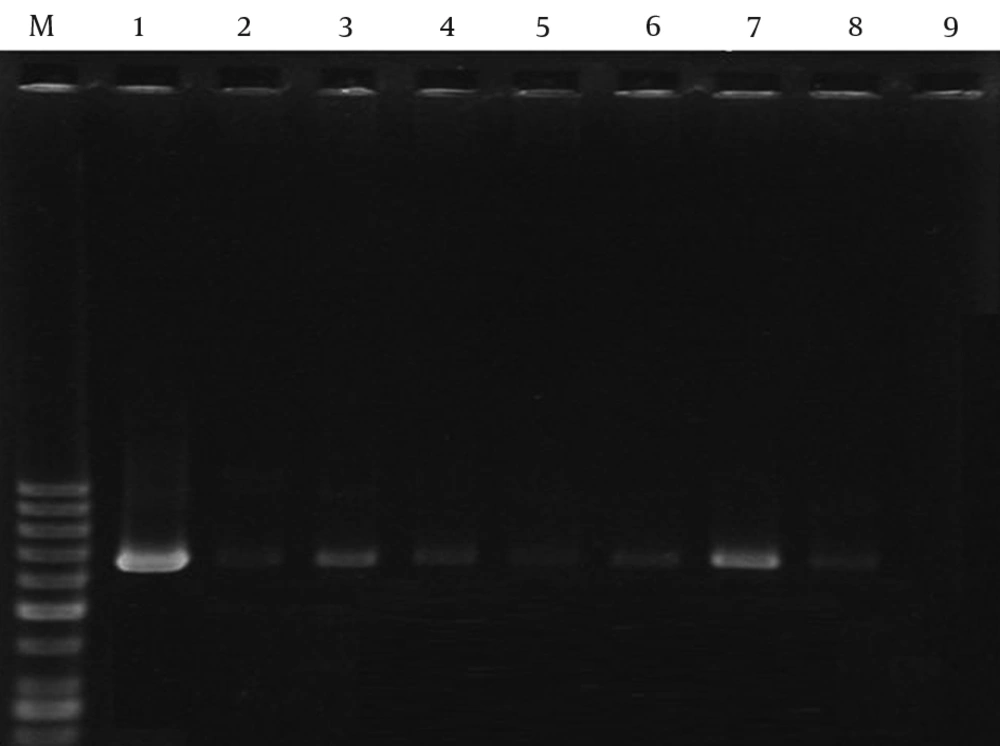

The PCR was standardized for detecting two virulence associated genes of L. monocytogenes, namely plcA, hlyA, using primer pairs of 5'-ATCAGT GAAGGGAAAATGCAAGAAG-3' and 5'-TTGTATAAGCAATGGGAACTCCTGG-3' specific for hlyA and 5'-ATGTTAAGTTGAGTACGAATTGCTC-3' and 5'-TACGATGAGCTATAACGGAGACATG-3'specific for plcA. The specificity of the standardized PCR was tested by screening the standard strain of L. monocytogenes (ATCC 7644). PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 μL, containing 12 μL PCR master mix, 8 vμL double distilled water (DDW), 1 μL (each) primer targeting the plcA or hlyA gene and 3 μL of the template DNA. The amplifications were carried out in master cycler (Eppendorf Co., Germany) using the following program for hlyA: 95°C for one minute, followed by 40 cycles (95°C for 30 seconds, 59 °C for 35 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds) and 72°C for five minutes; the amplification program for plcA was 95°C for one minute, followed by 40 cycles (95°C for 30 seconds,51°C for 35 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds) and 72°C for five minutes. The PCR products bands were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel at 95 V for 45 minutes in Tris-Borate-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TBE) 1X containing ethidium bromide under UV irradiation. The sequencing method was performed by Bioneer Company (Korea) and then the sequences were analyzed with Chromas 1.45 software and BLAST in NCBI.

3.6. Data Analysis:

All data were compiled, and analysis was done using spss version 17 and for survey of significance, χ2 (Chi-square test) was calculated. Minimal level of significance was considered P < 0.05.

4. Results

Among 96 samples from spontaneous abortions, four specimens were positive for L. monocytogenes by microbiological tests. The standardized PCR allowed amplification of virulence-associated genes of L. monocytogenes, namely plcA and hlyA, to 659 and 451 bp PCR products, respectively. Among 96 samples, L. monocytogenes was found in 16 samples entailing plcA and hlyA genes according to the PCR results (Figures 1 and 2).

Statistically, there was a significant difference between these two methods (P = 0.003). This study showed that PCR was more sensitive and specific than culture method.

The average age of the 96 women was 30.9 ± 4.7 years old and the average age of patients with positive L. monocytogenes PCR results was 33.5 ± 7.2 years old. Of 96 samples, 27 patients (28.1%) were low educated, 53 (55.2%) had a high school diploma and 16 (16.7%) had a college degree. High school graduates and low-educated patients had the highest incidence of Listeria compared with higher educated ones (11, 68.8%). Therefore, there was a significant association between patients positive forListeria and control samples regarding education; 95% CI [2.3-85.7 OR=12.2] (P = 0.00).

Of 96 patients, 12 (12.5%) had more than one abortion before and 84 (87.5%) did not have any abortion history. Of 16 patients positive for L. monocytogenes, 6 (37.5%) had abortion precedent. There was a significant association between patients with abortion precedence and with non-abortion precedence; 95% CI [1.7-33.5 OR=74] (P =0.001).

Analysis of all the samples indicates that of 16 patients positive for L. monocytogenes, 11 (68.8%) and 5 (31.2%) were housewives and employed women, respectively. Hence, there was no significant association between the housewives and the employed women (P = 0.9). The investigation of contraception methods also showed that there was no significant association between women with positive and negative Listeria regarding the contraception methods (Table 1). We did not encounter any missing value, either.

| Variables | Prevalence of L. monocytogenes by PCR | Prevalence of L. monocytogenes by Culture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Education | ||||||

| Low level of education | 3 | 24 | 27 | 2 | 25 | 27 |

| High school diploma | 11 | 42 | 53 | 2 | 51 | 53 |

| Higher than diploma | 2 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 16 | 16 |

| Total | 16 | 80 | 96 | 4 | 92 | 96 |

| Age | ||||||

| Lower than 20 years | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 21-30 Years | 8 | 33 | 41 | 3 | 38 | 41 |

| 31-41 Years | 8 | 46 | 54 | 1 | 53 | 54 |

| Total | 16 | 80 | 96 | 4 | 92 | 96 |

| Abortion precedence | ||||||

| Abortion precedence | 6 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Non-abortion Precedence | 10 | 74 | 84 | 2 | 82 | 84 |

| Total | 16 | 80 | 96 | 4 | 92 | 96 |

| Job | ||||||

| Housewife | 11 | 66 | 77 | 3 | 74 | 77 |

| Employed | 5 | 14 | 19 | 1 | 18 | 19 |

| Total | 16 | 80 | 96 | 4 | 92 | 96 |

| Contraception methods | ||||||

| Natural | 7 | 27 | 34 | 2 | 32 | 34 |

| Other methods | 9 | 53 | 62 | 2 | 60 | 62 |

| Total | 16 | 80 | 96 | 4 | 92 | 96 |

aAbbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

bData are presented as No.

5. Discussion

Few human listeriosis cases have been reported in Iran. This can be due to imperfect identification or isolation methods, lack of awareness, and low incidence rate in some regions. Approximately, one-third of reported human listeriosis is associated with pregnancy, causing spontaneous abortions, especially in the second or third trimester (10).

In the present study, 16 and four isolates of L. monocytogenes were recovered from human abortion cases by PCR and culture, respectively. The rate of L. monocytogenes identified by PCR was 16.7%. The result of the used methods as well as the data analysis showed that L. monocytogenes can be a causative agent of abortion in pregnant women.

A number of factors are involved in manifestation of L. monocytogenes virulence. Detection of only one virulence-associated gene by PCR is not always sufficient to identify L. monocytogenes(11, 12). Moreover, two genes (plcA and hlyA) were investigated in our study. L. monocytogenes phospholipases are essential determinants of pathogenicity and thus, we investigated them as well (5). plcA and hlyA existed in all the positive cases (16). In a study by Kaur et al. the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in India reported four isolates from 305 samples comprising blood, urine, and placental bits, faecal and vaginal swabs that were collected from 61 patients with spontaneous abortion samples. Another result of this research was that plcA and its expression had key roles in virulence determination of L. monocytogenes (5).

Shayan et al. reported 36 isolates of L. monocytogenes in Iran with PCR method and 7 isolates with culture, among 100 vaginal samples. In accordance with this study, PCR was faster, more sensitive and more specific than culture method for identifying L. monocytogenes in vaginal swabs. Because of some factors like the number of samples and country similarity, the results of this research were similar to our results (13).

In a research study conducted by Kargar et al. in Iran, out of 311 samples (urine, blood, placenta and cervix), no positive cases were detected by culture method, but 10.28% prevalence for L. monocytogenes by PCR for hlyA was identified. There was similarity between Kargar’s research and our study in abortion precedence. This similarity can be related to country conditions and similar applied methods (14). Based on the survey of Ahmed et al., 71 examined seafood samples, 20 (28.2%) were identified with L. monocytogenes, 15 (75%) of which were confirmed as virulent strains. In addition, of 50 human stool samples, only 1 (2%) was identified with virulent L. monocytogenes (15).

The results of the study of Chao et al. in china showed that of 548 samples, 32 strains (5.8%) were isolated from pre-prepared foods in markets and the average prevalence was 13.06% by PCR method for hlyA. The study showed that the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in pre-prepared foods in markets was significantly higher than those in cooked foods of hotels and restaurants. The difference of results between our study and that of Chao’s can be explained by samples differences (16).

Based on Jahangirsisakht et al. study in Iran, among 311 samples collected from 107 pregnant women (including urine, blood, placenta and cervix swab), 190 specimens were from pregnant women with a history of abortion and 120 from cases with normal delivery. Among 107 pregnant women, L. monocytogenes hlyA gene was detected in 11 (10.28%), with the highest frequency in the age group of 26-30 years old. The mean age of participants was 26.7 years old and almost 64% of positive samples were taken from cervix. The results of this survey were similar to the outcomes of our study; in addition, the samples and the studied genes were alike in both (17).

The result of Goudarzi et al. study showed that out of a total of 87 blood samples, 12 were detected positive for L. monocytogenes using both culture and PCR methods. The results also showed a significant statistical relationship between recurrent abortions and level of education using PCR (P < 0.05). Because of several factors like age, positive cases and education, the results of this study and our study had more similarity compared to other researches (18).