1. Introduction

Carbapenems, including imipenem (IMP), meropenem (MEM), and ertapenem (ERP) are the last resort for extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) producing bacteria (1). Unfortunately, today, the emerging of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) or Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) is a concern in the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections (2). CRE infections are associated with a high mortality rate (3).

One of the most important carbapenemases is recently known as New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (blaNDM-1), which belongs to class B β-lactamases or metallo-β-lactamases (MBL) (4). For the first time, blaNDM-1was detected from Klebsiella pneumonia isolated from a urinary tract sample from a Swedish patient who had been hospitalized in India (5). Today, blaNDM-1was detected in other bacterial species including Escherichia coli (E. coli) (6). The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant E. coli strains isolated from Iran is very low. In 2 recent studies, the susceptibility of E. coli isolates to imipenem was reported as 99.3% (7) and 100% (8). However, the appearance of carbapenemases gene, especially blaNDM-1, can be a serious risk factor in increasing carbapenem resistance rates among the E. coli strains or other bacteria.

Here, we report emergence of blaNDM-1- producing E. coli strains in Iran for the first time.

2. Case Presentation

In September 2015 and June 2016, 2 swab samples from burn wound infections of a 64 year old woman as well as a 54-yr-old woman, who had been hospitalized in Motahari hospital (Iran University of medical sciences, Tehran, Iran) for a third-degree burning, were taken. The 2 patients used silver sulfadiazine, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, TMP/SMX, and ceftazidime as medication. The swabs were transferred to transport medium and sent to the microbiology lab of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science for isolation of bacterial strains. Standard identification methods including phenotypic survey on MacConkey Agar (Merck, Germany), TSI (Merck, Germany), IMViC, motility, urea (Merck, Germany) mediums, and also oxidase test, confirmed the identity of isolates as E. coli strains.

Antibiotic susceptibility test of the isolates by disk diffusion method for carbapenems including imipenem, IMP (10 μg), meropenem, MEM (10 μg), and ertapenem, ERP (10 μg) showed that the isolates are resistant to the antibiotics. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of imipenem and meropenem (Jaber Ebne Hayyan Pharmaceutical Company, Iran) were determined as 8 and 64 µg/mL, respectively, by the microdilution method. Furthermore, the isolates were resistant to several common antibiotics including, piperacillin, PIP (100 μg), amoxicillin clavulanate, AMC (20/10-μg), gentamicin, GEN (10 μg), amikacin, AMN (30 μg), cefepime, CEFp (30 μg), ciprofloxacin, CIP (5 μg), cefazolin, CEFz (30 μg), ceftriaxone, CEFx (30 μg), cefoxitin, CEFo (30 μg), TMP/SMX (25 μg), and aztreonam, AZT (30 μg). All antibiotic disks were purchased from Rosco Diagnostica Taastrup, Denmark. However, nitrofurantoin, NIT (300μg), is the only antibiotic, which the carbapenem resistant isolates are sensitive to it.

Phenotypic detection of β-lactamases was done by Combined Disk Test (CDT) using ceftazidime (CAZ; 30 μg), ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (CAZ30/CLAV10), and boronic acid (BA; 250 μg) disks for blaAmpC detection. Additionally, CDT test was used for blaMBL detection using 2 IPM (10 μg) disks and EDTA 0.5 M solution. Results showed that the strains do not produce blaAmpC, whereas they can produce blaMBL enzyme.

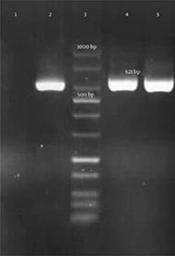

Genotypic detection of blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM-1 (Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase), blaVIM-1– blaVIM-37, blaDIM-1(Dutch imipenemase), and blaNDM-1 genes was done by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification method and further sequencing of PCR products. All primer sequences are shown in Table 1. The presence of the mentioned genes in carbapenem-resistant isolates were not confirmed by PCR. However, a 621-bp band was amplified by blaNDM-1 primers and further DNA sequencing confirmed the presence of blaNDM-1gene in these 2 E. coli isolates (Figure 1). E. coli ATCC 25922 was considered as a control in all tests.

| Gene Name | Primer Sequence | Product Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaKPC | Forward: 5′- ATG TCT GTA TCG CCG TCT -3′ | 989-bp | (9) |

| Reverse: 5′-TTTTCAGAGCCTTACTGCCC-3′ | |||

| blaIMP-1 | Forward:5′- -GAAGGCGTTTATGTTCATAC -3′ | 587-bp | (10) |

| Reverse: 5′- GTACGTTTCAAGAGTGATGC -3′ | |||

| blaVIM-1 | Forward: 5′-AGTGGTGAGTATCCGACAG-3′ | 836-bp | (11) |

| Reverse: 5′-ATGAAAGTGCGTGGAGAC-3′ | |||

| blaVIM-1– VIM-37 | Forward: 5′-GATGGTGTTTGGTCGCATA -3′ | 390-bp | (12) |

| Reverse: 5′-CGAATGCGCAGCACCAG -3′ | |||

| blaDIM | Forward: 5′- GCTTGTCTTCGCTTGCTAACG -3′ | 699-bp | (13) |

| Reverse: 5′- CGTTCGGCTGGATTGATTTG -3′ | |||

| blaNDM-1 | Forward: 5′- GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC -3′ | 621-bp | (14) |

| Reverse: 5′- CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC -3′ |

3. Discussion

This is a first report on emerging of blaNDM-1producing E. coli in Iran. Earlier, Shahcheraghi et.al reported the first blaNDM-1producing K. pneumonia in Iran (15). Furthermore, recently, Fazeli et.al presented the 2nd report on the detection of blaNDM-1gene among K. pneumonia isolates from Iran (16). Approximately, the emergence of blaNDM-1producing Enterobacteriaceae is reported in all neighboring countries including; Turkey (17), Iraq (18), Pakistan (19), and Afghanistan (20). The prevalence of blaNDM-1producing Enterobacteriaceae was reported from different countries as follows: 2.7 % in Kuwait (6), 1.2 % in India, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom (19), as well as 1.1 % in Vietnam (21). Among these blaNDM-1producing Enterobacteriaceae, the prevalence of E. coli was very significant: 19 % in Kuwait (6), 20 % in India, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom (19), as well as 12.26 % in Vietnam (21). The blaNDM-1gene is placed near various insertion elements on transferrable plasmids (22). Medical tourisms has a considerable role in wide spreading of resistant genes e.g. blaNDM-1gene (19). In addition, the presence of blaNDM-1producing bacteria in environmental samples such as drinking-water samples could be involved in spreading of the resistant gene (23). Spreading of blaNDM-1gene is a global concern. Isolates harboring blaNDM-1gene are resistant to almost all β-lactam antibiotics, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides (19). These isolates can be eradicated by aztreonam, colistin, and tigecycline (24). However, resistance to these antibiotics may be developed as the blaNDM-1harboring E. coli strains in our study were also resistant to aztreonam.

In conclusion, our results show the emerging of carbapenem-resistant genes, especially blaNDM-1, is an alarm to our health system, due to the spreading of transferable blaNDM-1gene among pathogenic bacteria, which resulted in the emergence of multi drug resistant photogenes, which are resistant to all available antibiotics. Therefore, early identification of blaNDM-1harboring bacteria and prevention of their spreading must be performed in any region.