1. Background

Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus (HTLV), a major source of adult T-cell leukemia and related diseases, is endemic to northeastern Iran and Neyshabur, and was detected to be higher than other cities, according to previous reports (1, 2). Japan, Africa, Caribbean Islands, and South America are the most prevalent for Human T-cell lymphotropic virus (3, 4).

The HTLV infection is considered as a public health challenge in endemic areas so that HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infection rate has been reported as 0.26% and 0% in Mashhad (the first populous city in Razavi Khorasan), respectively (5, 6). According to a recent study, Neyshabour, as the second populous city in Razavi Khorasan, has a rate of 6.55% (2). The prevalence rates of HTLV-1 infection in successive three years of Sabzevar (the third populous city of Razavi Khorasan) study was 0.19%, 0.14%, and 0.09%, respectively (7).

The prevalence of HTLV-1 infection in pregnant females, in countries such as Ghana, Burkina-Faso, Gabon, Jamaica, Haiti, Japan (Okinawa), Italy, Greece, French Guyana, Brazil (Mato Grosso), Brazil (Sao Luis), Peru (Andes, Coast, Jungle, Lima), Argentina (Cordoba-Central) were found to be 2.1% (8), 1% (9), 2.1% (10), 3.8% (11), 4.2% (12), 3.9% (13), 0.02% (14), 0% (15), 4.2% (12), 0.2% (16), 0.2% (17), 1.3% (18) and 0.1% (19) respectively .

Modes of HTLV transmission are the same as human immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (18) and for a long time, infected carriers remain asymptomatic so that these people serve as a potential source for the transmission of the virus (20). There are some studies, which have indicated that the north-eastern Iran has high endemicity of HTLV infection (1, 2, 21-23), yet they are not conducted on young females as a sensitive and important part of the society in this region.

2. Objectives

The aim of this investigation was to determine the prevalence of HTLV infection among young females attending a large medical diagnostic laboratory in Neyshabour, Northeast of Iran, during years 2011 to 2015.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

An epidemiologic survey was carried out in Neyshabur between 2011 and 2015 among healthy young females. A total of 5724 healthy individuals from Neyshabur, North-Eastern Iran, were included in this study. The prevalence of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infections was established by collected data from the surveillance system during 2011 to 2015. The sample of the study was a biased sample and also some other laboratories were involved in this study. The participant’s personal data were confidential. Investigated variables were age, year, and season.

3.2. Serological Assays and Confirmation Tests

The HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 kit (Dia. Pro Diagnostic Bioprobes, Italy) that had a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 98% and Stat Fax 3200 (USA) ELISA reader were used based on available instructions (24). Based on laboratory policy, all borderline results were evaluated again after one month.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20, Armonk, NY, IBM Corp.). The chi-square test with significance level of 0.05 was used.

3.4. Ethical Approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the Research and Technology deputy of ACECR, Mashhad Branch.

4. Results and Discussion

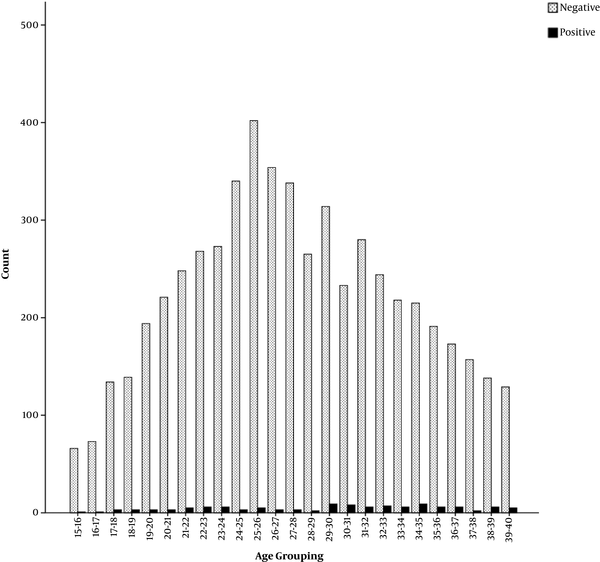

Overall, 5724 participants were evaluated in the present study. Participants' mean age was 28.22 ± 6 years. Overall, 117 (2.04 %) had evidence of antibodies to HTLV-1 and HTLV-2, according to the ELISA results. Most participants were aged 25 to 26 years old (Figure 1).

The prevalence was significantly more common in older than younger females (ranged from 15 to 40 years old) (Tables 1 and 2). Most infected young females were aged 38 to 39 years (4.16%). The total prevalence of HTLV-1 and HTLV- 2 in each year is indicated in Table 3; based on the results, the highest prevalence was found in 2012 and gradually decreased with passing time (P < 0.0001). Seasonal prevalence investigation demonstrated that 3.16% of infected young females had referred in October.

| Variable | No. | Positive Cases (%) | Odd Ratio (OR) | CL 95% | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||||

| 15 - 28 | 3095 | 45 (1.45) | 1.908 | 1.31 - 2.78 | 0.001 |

| 29 - 40 | 2629 | 72 (2.74) |

Age-Based Distribution of Women and Overall HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 Cases of Screening During 2010 To 2015

| Age Grouping | Negative | Positive (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 - 16 | 66 | 1 (1.49) | 67 |

| 16 - 17 | 73 | 1 (1.35) | 74 |

| 17 - 18 | 134 | 3 (2.19) | 137 |

| 18 - 19 | 139 | 3 (2.11) | 142 |

| 19 - 20 | 194 | 3 (1.52) | 197 |

| 20 - 21 | 221 | 3 (1.33) | 224 |

| 21 - 22 | 248 | 5 (1.97) | 253 |

| 22 - 23 | 268 | 6 (2.19) | 274 |

| 23 - 24 | 273 | 6 (2.15) | 279 |

| 24 - 25 | 340 | 3 (0.87) | 343 |

| 25 - 26 | 402 | 5 (1.22) | 407 |

| 26 - 27 | 354 | 3 (0.84) | 357 |

| 27 - 28 | 338 | 3 (0.89) | 341 |

| 28 - 29 | 265 | 2 (0.75) | 267 |

| 29 - 30 | 314 | 9 (2.78) | 323 |

| 30 - 31 | 233 | 8 (3.31) | 241 |

| 31 - 32 | 280 | 6 (2.09) | 286 |

| 32 - 33 | 244 | 7 (2.79) | 251 |

| 33 - 34 | 218 | 6 (2.68) | 224 |

| 34 - 35 | 215 | 9 (4.01) | 224 |

| 35 - 36 | 191 | 6 (3.04) | 197 |

| 36 - 37 | 173 | 6 (3.35) | 179 |

| 37 - 38 | 157 | 2 (1.26) | 159 |

| 38 - 39 | 138 | 6 (4.16) | 144 |

| 39 - 40 | 129 | 5 (3.73) | 134 |

More Detailed Age-Based Distribution of Women Who Referred for HTLV-1 and HTLV -2 Screening During 2010 to 2015a

| Year | Number | HTLV-1 & HTLV-2 -Positivity Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Positive: 10 Total: 1185 | 0.84 |

| 2014 | Positive: 18 Total: 1259 | 1.43 |

| 2013 | Positive: 24 Total: 1157 | 2.07 |

| 2012 | Positive: 39 Total: 1124 | 3.46 |

| 2011 | Positive: 26 Total: 999 | 2.60 |

The Annual Prevalence of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 Investigated in This Studya

The present study showed that participants were mostly aged 25 to 26 years old (Figure 1) because of the fact that pregnancy and marriage events usually take place in this range of age and women need to perform screening tests, including HTLV.

Some previous studies in Neyshabour have demonstrated that the prevalence of HTLV1, HTLV-1 and HTLV -2 among females (ranged 1 to 100) were 5.17 % and 4.94%, respectively (1, 2). In comparison with the current study, about 4.16% of infected young females were aged 38 to 39 years. After the year of 2012, the total HTLV-1 and HTLV- 2 prevalence begun to significantly decrease (Table 3). It is speculated that greater awareness of the public is more likely the reason of this promising decrease. The current results were also in agreement with the endemicity of HTLV in the general population of Neyshabour (2). It must be considered that age is the most important factor, which had the highest impact on infection. The researchers did not take account of older females of more than 40 years in the present study. Thus, the prevalence of HTLV-1 and HTLV- 2 was lower than the two mentioned studies. In 2013, another study indicated that the prevalence rate among young females, aged 13 to 19 and 20 to 35 were 0.26 and 2.13, respectively (22). Considering Tables 1 and 2, it is clear that the prevalence was more significantly common in older than younger females (ranged from 15 to 40 years old), however, it was not significant in detailed age grouping (P = 0.239).

The HTLV-1 antibodies seroprevalence among the pregnant females, who attended the antenatal clinic at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital was 0.5% (25). A study performed in Rio de Janeiro showed the prevalence among pregnant females was equivalent to 0.66% (26). A Japanese study reported that the prevalence rate of HTLV-1 among pregnant females was 0.1% (27). During two successive years (From March 2011 to April 2013), Hatami et al. (28) showed the prevalence of HTLV-1 was 0.5% among blood donor females (aged 17 to 59) in Mashhad. About 1864489 blood donations were evaluated for HTLV-1 by karimi et al., and there were 0.098% infected donators (29).

In the present study, 2.04% of healthy young females were positive for HTLV-1 and HTLV- 2 by the ELISA test during the five years. This highlights that Neyshabur is an endemic region for HTLV infection. Young females are most susceptible for vertical transmission of HTLV infection to next generations. The prevalence of the infection among pregnant females in Neyshabur is a little higher than other parts of Razavi Khorasan province (1). According to pregnancy, which usually takes place in young females and the high positivity rate (2.04 %) demonstrated in the present study; the researchers suggested that health authorities should pay more attention to this health matter. Also, screening must be carried out in all young females whether they have been married or not.

This study, for the first time indicated the seasonal prevalence of HTLV-1 and HTLV -2 from 2011 to 2015 (Table 4). The month of October had the highest referrals by infected young females (3.16%). However, this research did not find any significant relationship between month and HTLV infection.

| Month | Negative | Positive (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| April | 487 | 11 (2.2) | 498 |

| August | 440 | 10 (2.22) | 450 |

| December | 525 | 7 (1.31) | 532 |

| February | 464 | 10 (2.1) | 474 |

| January | 435 | 8 (1.8) | 443 |

| July | 510 | 13 (2.48) | 523 |

| June | 413 | 10 (2.34) | 423 |

| March | 442 | 11 (2.42) | 453 |

| May | 613 | 7 (1.13) | 620 |

| November | 503 | 13 (2.51) | 516 |

| October | 367 | 12 (3.16) | 379 |

| September | 408 | 5 (1.21) | 413 |

The Seasonal Prevalence of HTLV-1 and HTLV -2 from 2011 to 2015a

4.1. Conclusion

The data obtained suggests that Neyshabour, as a second populous city in Razavi Khorasan, is a high endemic city of HTLV infected young females. Making females aware in educational facilities seems to be vital to avoid the transfer of HTLV infection, especially to the next generations. Further investigations, such as population-based studies are required to confirm these results. Development of strategies seems to be necessary for decreasing this infection among young females in the main endemic city of Iran.