1. Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are of global public health problems (1). Among different known STIs, chlamydial and mycoplasmal infections are of great concern because of their association with postoperative difficulties and termination of pregnancy (TOP) (1). Although the causative agents are entirely different, they have similar clinical manifestations (2). It has been reported that C. trachomatis, M. genitalium, and U. urealyticum are all involved in genitourinary tract infections, abortions, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), and prenatal mortality or stillbirth (3).

C. trachomatis is of the most important common pathogens involved in sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) worldwide, accounting for 600,000 reported cases annually in USA (3, 4). It is a major cause of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), mucopurulent cervicitis, tubal infertility (5), ectopic pregnancies, preterm birth, and cervical or ovarian cancers (2-4). According to the Center for Disease Control, approximately 4.7% - 14% of C. trachomatis infections occur during pregnancy (6).

In Iran, the isolation frequency of C. trachomatis was reported to be up to 23% in pregnant women (7, 8) and about 11% - 13% in women with abortion (7-9). Among other causative agents of STDs, there are Mycoplasma spp. including M. genitalium and U. urealyticum. These organisms are free-living with small genomes and low metabolic activities, and their association with nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) has been reported (10). In this respect, the prevalence of M. genitalium among female partners of men infected with NGU has been reported to be 32% (10). M. genitalium has also been detected in 56% of male sexual partners of infected women (11). The role of M. genitalium in more severe infections such as cervicitis and PID has been demonstrated (12), and a significant association has been reported between M. genitalium infection and preterm birth, younger maternal age, and low body mass index (13). U. urealyticum is among the most common organisms causing adverse infections of the amniotic fluid and placenta (9). It is known as a normal flora in the lower genital tract, but its association with STDs is still controversial (9). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the frequencies of C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, and M. genitalium infections in pregnant or women with abortion in southeast of Iran.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of infections with mentioned organisms in vaginal samples of women with abortion in comparison with pregnant women. Besides, the association between the presence of these infections and socio-demographic parameters was determined.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

In this cross-sectional study conducted from December 2015 to December 2016, 200 vaginal swabs were taken from 124 women who had experienced abortions and 76 pregnant women referring to /or hospitalized at the gynecology department of a university-affiliated hospital in Kerman, Iran. The sample size was determined by an expert statistician. All the volunteers enrolled in this study were asked for some socio-demographic data (e.g., age, education, and place of residence), history of abortion, premature delivery, genital and urinary tract infections through filling out a questionnaire and face to face interviews (Table 1).

| Characteristicb | Total | Pregnant Group, N = 76 | Abortion Group, N = 124 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | |||

| ≤ 25 | 62 (31) | 25 (32.9) | 37 (29.8) |

| 26 - 35 | 99 (49.5) | 40 (52.6) | 59 (47.8) |

| > 35 | 35 (17.5) | 7 (9.2) | 28 (22.6) |

| Gestational age (week) | |||

| 1 - 10 | 50 (25) | 2 (2.6) | 48 (38.7) |

| 11 - 20 | 75 (37.5) | 3 (3.9) | 76 (61.3) |

| 21 - 30 | 14 (7) | 10 (13.2) | 0 |

| 31 - 40 | 60 (30) | 60 (78.9) | 0 |

| > 40 | 1 (5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 |

| Locality | |||

| Kerman | 92 (46) | 34 (44.7) | 58 (46.8) |

| Township | 87 (43.5) | 32 (42.1) | 55 (44.4) |

| Others | 14 (7) | 3 (3.9) | 11 (8.9) |

| Mother education | |||

| Under diploma | 70 (35) | 28 (36.8) | 42 (33.9) |

| Diploma | 74 (37) | 27 (35.5) | 47 (37.9) |

| Upper diploma | 49 (24.5) | 14 (18.4) | 35 (28.2) |

| Patient’s job | |||

| Housekeeper | 167 (83.5) | 59 (77.6) | 108 (87.1) |

| Employee | 26 (13) | 10 (13.2) | 16 (12.9) |

| Husband’s job | |||

| Governmental | 46 (23) | 16 (21.1) | 30 (24.2) |

| Non-governmental (driver, …) | 147 (73.5) | 53 (69.7) | 94 (75.8) |

| Intercourse (week) | |||

| ≤ 3 | 161 (80.5) | 56 (73.7) | 105 (84.7) |

| > 3 | 32 (16) | 13 (17.1) | 19 (15.3) |

| Contraception method | |||

| Withdrawal | 134 (67) | 52 (68.4) | 82 (66.1) |

| Condom | 23 (11.5) | 6 (7.9) | 17 (13.7) |

| Other | 36 (18) | 11 (14.4) | 25 (20.1) |

| Type of delivery | |||

| NVD | 78 (39) | 27 (35.5) | 51 (41.1) |

| Caesarian | 45 (22.5) | 9 (11.8) | 36 (29) |

| First delivery | 70 (35) | 33 (43.4) | 37 (29.8) |

| Previous TOP | |||

| None | 111 (55.5) | 44 (57.9) | 67 (54) |

| One or more | 82 (41) | 25 (32.9) | 57 (46) |

| History of genital infection | |||

| Yes | 78 (39) | 27 (35.5) | 51 (41.1) |

| No | 115 (57.5) | 42 (55.3) | 73 (58.9) |

| History of genital surgery | |||

| Yes | 22 (11) | 10 (13.2) | 12 (9.7) |

| No | 171 (85.5) | 59 (77.6) | 112 (90.3) |

| History of PROM | |||

| Yes | 38 (19) | 13 (17.1) | 25 (20.2) |

| No | 155 (77.5) | 56 (73.7) | 99 (79.8) |

Demographic Data and Risk Factors of Women Referring to Afzalipour Hospital, Kerman, Irana

3.2. Samples and Microbiological Procedures

Specimen collection was performed by inserting 2 - 3 cm of a Dacron swab (Delta Lab, Spain) into the vagina and rotating it in order to obtain a great number of cells. All the specimens were placed into Trypticase soy broth (Conda, Spain) containing 0.6% yeast extract (BBL, USA) and were transferred on ice to laboratory for further processing (14). DNA extraction was performed using High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Eluted DNA was stored at -20°C for further analysis.

3.3. PCR Assay

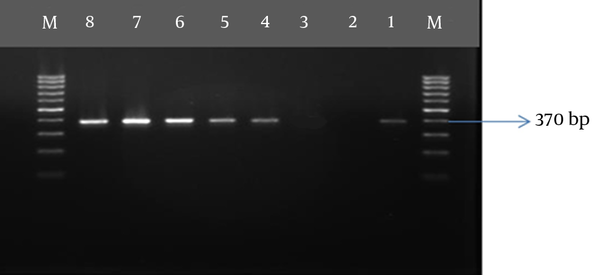

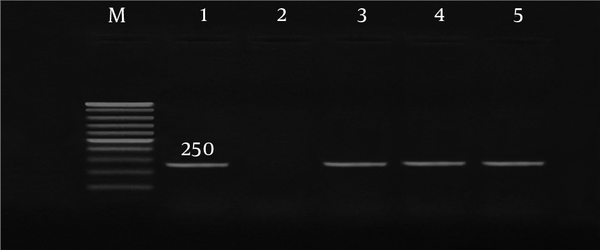

DNA extraction and amplification for all polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and nested PCR assays were performed using Pars Tous kit (Arya Tous CO. Iran), which amplifies outer membrane protein 1 (omp 1) of C. trachomatis, P protein (mgpa) of M. genitalium, and urease of U. urealyticum (9, 15, 16). For C. trachomatis, nested PCR was performed according to the kit’s instructions (Table 2). The amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gel.

| Gene | Annealing Temperature °C (Time) | Extension Temperature °C (Time) | Number of Cycles | Amplication Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omp 1 of C. trachomatis | 55 (40 s) | 72 (30 s) | 30 | 500 |

| Mgpa (P protein of M. genitalium) | 56 (40 s) | 67 (30 s) | 40 | 255 |

| Urease (urease of U. urealyticum) | 57 (40 s) | 72 (30 s) | 40 | 370 |

PCR Protocol for Detection of U. urealyticum and M. genitalium and Nested PCR for C. trachomatisa

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 20. T-test was performed to analyze the relationship between the presence of infections and demographic variables. P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was performed under approval of institutional review board of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (IR.KMU.REC.1395.339). Written informed consent form was obtained from all the participant in this study.

4. Results

Overall, 200 women were recruited, of whom 92.7% were Iranian women and 7.3% were Afghans. The mean age of the pregnant women and those with abortion was 32 ± 2.8 and 31 ± 3.1 years, respectively. Also, history of genitourinary infection was reported in 40.42% of the subjects.

C. trachomatis was found in 15.32% (19/124) of aborted and 10.52% (8/76) of pregnant women. In the pregnant group, association between infection and gestational age was significant, such that 9.3% of the specimens from pregnant women which were positive for C. trachomatis, were recovered from women at the third trimester (vs. 1.32% for women with abortion; P ≤ 0.05). The frequency of the studied bacteria and co-infection rates are shown in Table 3.

| Bacterial Species | Groups, No. (%) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant Group, N = 76 | Abortion Group, N = 124 | ||

| C. trachomatis | 8 (10.52) | 19 (15.32) | ≥ 0.4 |

| M. genitalium | 13 (17.1) | 26 (21) | ≥ 0.6 |

| U. urealyticum | 12 (15.8) | 43 (34.13) | ≤ 0.006* |

| C. trachomatis and M. genitalium | 1 (1.3) | 5 (4.03) | ≥ 0.4 |

| C. trachomatis and U. urealyticum | 3 (3.9) | 9 (7.25) | ≥ 0.5 |

| M. genitalium and U. urealyticum | 2 (2.6) | 15 (12.1) | ≤ 0.03* |

Frequency of C. trachomatis, M. genitalium and U. urealyticum in Studied Groupsa

No co-infection with the three studied microorganisms was found, while co-infection with two microorganisms was more frequently found in abortion group (23.3%) in comparison with pregnant one (7.89%). However, only high frequency of co-infection with M. genitalium and U. urealyticum was statistically significant (P = 0.03; Table 3).

Co-infection with C. trachomatis and M. genitalium was only detected in Afghan women older than 25 years old, while co-infection with C. trachomatis and U. urealyticum was more frequently observed in women younger than 25 years old who had history of vaginal infection and PROM; however, this difference was not significant. Co-infection with C. trachomatis and U. urealyticum was mostly detected in women who had previously experienced abortion. The demographic data of C. trachomatis, M. genitalium, and U. urealyticum-positive patients are summarized in Tables 4 and 5 in both pregnant and abortion groups. Gel agarose electrophoresis for detection of genes representative for C. trachomatis, M. genitalium, and U. urealyticum are displayed in Figures 1 - 3.

| Characteristic | C. trachomatis | P Value | M. genitalium | P Value | U. urealyticum | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.932 | 0.972 | 0.691 | |||

| ≤ 25 | 3/25 (12) | 4/25 (16) | 3/25 (12) | |||

| 26 - 35 | 4/40 (10) | 7/40 (17.5) | 8/40 (20) | |||

| > 35 | 1/7 (14.29) | 1/7 (14.29) | 1/7 (14.29) | |||

| Gestational age (week) | 0.050* | 0.659 | 0.490 | |||

| 1 - 10 | 0/2 (0) | 0/2 (0) | 0/2 (0) | |||

| 11 - 20 | 0/3 (0) | 0/3 (0) | 1/3 (33.33) | |||

| 21 - 30 | 1/10 (10) | 3/10 (30) | 0/10 (0) | |||

| 31 - 40 | 6/60 (10) | 10/60 (16.67) | 11/60 (18.34) | |||

| > 40 | 1/1 (100) | 0/1 (0) | 0/1 (0) | |||

| Locality | 0.286 | 0.044* | 0.690 | |||

| Kerman | 6/34 (17.65) | 2/34 (5.88) | 5/34 (14.70) | |||

| Township | 2/32 (6.25) | 9/32 (28.12) | 6/32 (18.75) | |||

| Others | 0/3 (0) | 1/3 (33.34) | 1/3 (33.33) | |||

| Mother’s education | 0.406 | 0.866 | 0.375 | |||

| Under diploma | 3/28 (10.72) | 5/28 (17.85) | 5/28 (17.85) | |||

| Diploma | 2/27 (7.41) | 4/27 (14.81) | 3/27 (11.11) | |||

| Upper diploma | 3/14 (21.43) | 3/14 (21.42) | 0.235 | 4/14 (28.57) | ||

| Patient’s job | 0.327 | 0.556 | ||||

| Housekeeper | 6/59 (10.17) | 9/59 (15.25) | 10/59)16.94) | |||

| Employee | 2/10 (20) | 3/10 (30) | 2/10 (20) | |||

| Husband’ s job | 0.401 | 0.434 | 0.566 | |||

| Governmental | 1/16 (6.25) | 2/16 (12.5) | 3/16 (18.75) | |||

| Non - governmental (driver, …) | 7/53 (13.21) | 10/53 (18.86) | 9/53 (16.98) | |||

| Intercourse (week) | 0.530 | 0.402 | 0.283 | |||

| ≤ 3 | 7/56 (12.5) | 9/56 (16.07) | 11/56 (19.64) | |||

| > 3 | 1/13 (7.69) | 3/13 (23.07) | 1/13 (7.69) | |||

| Contrace ption method | 0.361 | 0.851 | 0.851 | |||

| Withdrawal | 7/52 (13.46) | 10/52 (19.23) | 10/52 | |||

| Condom | 1/6 (16.67) | 1/6 (16.67) | 1/6 (16.67) | |||

| Others | 0/11 (0) | 1/11 (9.09) | 1/11 (9.09) | |||

| Type of delivery | 0.050 | 0.309 | 0.543 | |||

| NVD | 1/27 (3.7) | 3/27 (11.11) | 3/27 (11.11) | |||

| Caesarian | 3/9 (33.34) | 3/9 (33.33) | 2/9 (22.23) | |||

| First delivery | 4/33 (12.13) | 6/33 (18.18) | 7/33 (21.21) | |||

| Previous TOP | 0.107 | 0.548 | 0.221 | |||

| None | 3/44 (6.8) | 8/44 (18.18) | 6/44 (16.64) | |||

| One or more | 5/25 (20) | 4/25 (16) | 6/25 (24) | |||

| History of genital infection | 0.146 | 0.127 | 0.297 | |||

| Yes | 5/27 (18.51) | 5/27 (18.51) | 6/27 (33.33) | |||

| No | 3/42 (7.14) | 7/42 (16.67) | 6/42 (14.29) | |||

| History of genital surgery | 0.327 | 0.544 | 0.556 | |||

| Yes | 2/10 (20) | 0/10 (0) | 2/10 (20) | |||

| No | 6/59 (10.16) | 12/59 (20.33) | 10/59 (16.95) | |||

| History of PROM | 0.470 | 0.402 | 0.402 | |||

| Yes | 2/13 (15.38) | 3/13 (23.07) | 3/13 (23.07) | |||

| No | 6/56 (10.71) | 9/56 (16.07) | 9/56 (16.07) |

| Characteristic | C. trachomatis | P Value | M. genitalium | P Value | U. urealyticum | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.766 | 0.800 | 0.670 | |||

| ≤ 25 | 7/37 (8.10) | 9/37 (24.32) | 15/37 (40.54) | |||

| 26 - 35 | 8/59 (13.55) | 11/59 (18.64) | 19/59 (32.20) | |||

| > 35 | 4/28 (14.29) | 6/28 (21.42) | 9/28 (32.14) | |||

| Gestational age (week) | 0.857 | 0.471 | 0.695 | |||

| 1 - 10 | 7/48 (14.58) | 9/48 (18.75) | 15/48 (31.25) | |||

| 11 - 20 | 12/76 (15.79) | 17/76 (22.37) | 28/76 (36.85) | |||

| Locality | 0.119 | 0.556 | 0.719 | |||

| Kerman | 7/58 (12.07) | 12/58 (20.69) | 19/58 (32.75) | |||

| Township | 12/55 (21.82) | 13/55 (23.64) | 19/55 (34.54) | |||

| Others | 0/11 (0) | 1/11 (0.09) | 5/11 (45.45) | |||

| Mother’s education | 0.037* | 0.697 | 0.704 | |||

| Under diploma | 7/42 (16.67) | 10/42 (23.80) | 13/42 (39.45) | |||

| Diploma | 11/47 (23.4) | 8/47 (17.02) | 16/47 (34.04) | |||

| Upper diploma | 1/35 (2.85) | 8/35 (22.85) | 14/35 (40) | |||

| Patient’s job | 0.252 | 0.557 | 0.498 | |||

| Housekeeper | 18/108 (16.67) | 23/108 (21.3) | 38/108 (35.18) | |||

| Employee | 1/16 (6.25) | 3/16 (18.75) | 5/16 (31.25) | |||

| Husband’s job | 0.269 | 0.447 | 0.177 | |||

| Governmental | 3/30 (10) | 7/30 (23.34) | 13/30 (43.34) | |||

| Non - governmental (driver, …) | 16/94 (17.02) | 19/94 (20.22) | 30/94 (31.92) | |||

| Intercourse (week) | 0.410 | 0.175 | 0.136 | |||

| ≤ 3 | 17/105 (16.19) | 20/105 (19.04) | 39/105 | |||

| > 3 | 2/19 (10.52) | 6/19 (31.58) | 4/19 | |||

| Contraception method | 0.481 | 0.064 | 0.720 | |||

| Withdrawal | 15/82 (18.3) | 13/82 (15.85) | 30/82 (36.58) | |||

| Condom | 1/17 (5.89) | 7/17 (41.18) | 4/17 (23.52) | |||

| Others | 3/25 (12) | 6/25 (12) | 9/25 (36) | |||

| Type of delivery | 0.717 | 0.528 | 0.364 | |||

| NVD | 7/51 (13.72) | 10/51 (19.60) | 14/51 (27.45) | |||

| Caesarian | 7/36 (19.44) | 6/36 (16.67) | 14/36 (38.89) | |||

| First delivery | 5/37 (13.51) | 10/37 (27.03) | 15/37 (40.54) | |||

| Previous TOP | 0.270 | 0.246 | 0.316 | |||

| None | 12/67 (17.92) | 12/67 (17.92) | 25/67 (37.32) | |||

| One or more | 7/57 (12.29) | 14/57 (24.57) | 18/57 (31.58) | |||

| History of genital infection | 0.559 | 0.376 | ||||

| Yes | 8/51 (15.69) | 10/51 (19.60) | 19/51 (37.26) | |||

| No | 11/73 (15.07) | 16/73 (21.92) | 0.469 | 24/73 (32.88) | ||

| History of genital surgery | 0.420 | 0.520 | 0.346 | |||

| Yes | 1/12 (8.34) | 2/12 (16.67) | 3/12 (25) | |||

| No | 18/112 (16.07) | 24/112 (21.42) | 40/112 (35.72%) | |||

| History of PROM | 0.326 | 0.240 | 0.474 | |||

| Yes | 5/25 (20) | 7/25 (28) | 8/25 (32) | |||

| No | 14/99 (14.14) | 19/99 (19.2) | 35/99 (35.35) |

5. Discussion

Abortion remains a major public health concern worldwide and is usually a consequence of serious genital tract infections. Among important genital bacteria causing infections, there are U. urealyticum, M. genitalium, and C. trachomatis (13, 17, 18). Depending on the type of sample and different methods of isolation, different frequencies for these bacteria are reported. For example, the frequencies of C. trachomatis among women with TOP in Swiss, Sweden, New Zealand, and Poland were 16.37%, 5.4%, 15.7%, and 32%, respectively (16, 19-21). In Iran (Tehran) and Iraq, the rates of 13.25% and 6.4% have been reported, respectively (9, 22). Our result is similar to the reported case from Swiss and higher than those reported from Iran (19).

In pregnant women, the prevalence of C. trachomatis has been reported from 1% in Saudi Arabia to 13.6% in Iraq (23-26). In Iran, the isolation of C. trachomatis from various regions was reported to range from 2.9% to 13.7% (8, 27-29). The frequency of C. trachomatis in this study was 10.52%, which is in line with the reported range of isolation from our country. The difference in the isolation frequency of these bacteria can be attributed to the type of samples, the methods of isolation, and understudied patients.

M. genitalium infection among women with TOP in Denmark, Sweden, and Iran in 2013 and 2014 ranged from 0.91% to 16.5%. Our results (21%) were in accordance with the reported case in Iran in 2014 (16, 23, 30, 31). The infection rates of M. genitalium among pregnant women in the UK, New Zealand, USA, and Sweden were 0.7%, 8.7%, 6.7 %, and 2.8%, respectively (16, 20, 32, 33). Besides, the prevalence of M. genitalium among pregnant women in various regions of Iran is varied, such that it was 1.02% in Sabzevar, 22.7% in Tonekabon, and 2.75% in Sanandaj (8, 23, 31). Herein, we observed that 22.41% and 17.1% of women with abortion and pregnant women were infected with M. genitalium, respectively, that is similar to Tonekabon report.

Difference in U. urealyticum isolation in various specimens has been reported, such that it was 10% among women with TOP in Iran and 74.1% in China (15, 34), and in pregnant women in Iran, it ranged from 7.3% to 15.2% (15, 35). In this study, U. urealyticum was isolated more frequently from the abortion group and we found a higher frequency of this bacterium than other studies in our country. The important role of U. urealyticum in various vaginal infections, resulting in pyelonephritis, PID, chorioamnionitis, and postpartum and postabortal fever, has been implicated in many studies (15). In addition, the co-infection of U. urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis has been reported to increase the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes in high-risk patients such as those with premature labor or PROM (36).

Various studies have focused on the relationship between risk factors and STIs in women (3). In some studies, association between maternal age (young women) and infection with C. trachomatis and M. genitalium has been reported (4, 7, 37). However, in other studies, in accordance with our research, no association was found between maternal age and the presence of C. trachomatis and M. genitalium (32). Other demographic factors that have been associated with these bacteria were contraceptive method, history of PROM, gestational age, and history of miscarriage (7, 15, 37, 38). In our study, there was a significant correlation between C. trachomatis infection and mother’s educational level in women who experienced abortion. Also, C. trachomatis infection was found to be significantly more prevalent in pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy compared to other times.

M. genitalium was found to be more frequent in rural and Afghan women in the pregnant group compared to the abortion group. Since neither the studied risk factors nor the study groups are similar in all studies, comparing the results is difficult. History of PROM was correlated with C. trachomatis infection according to Ahmadi et al. (7), while we found that history of PROM was more prevalent in patients co-infected with C. trachomatis and M. genitalium. There are some differences in cultural issues such as having different partners, which make comparison limited. Another limitation is the kind of specimen or sampling methods as well as various identification methods used in different studies. We used vaginal swabs for detection of the bacteria since this method is reported to give a high load of bacteria (9, 39).

In conclusion, we found that U. urealyticum is an important cause of infection in pregnant women in this region and its role in abortion and abnormalities needs special attention. Our follow-up studies indicated the important role of U. urealyticum in adverse outcomes of pregnancy. However, a higher number of cases should be examined and diagnostic screening tests should be performed in order to reduce the risk of premature stillbirth or abortions due to these infections. Gynecologists should adopt proper plans for the diagnosis and treatment of these infections in order to diminish the resulting complications in women.