1. Background

Antibiotic resistance in pathogens is a growing problem in all parts of the world, making infectious diseases difficult to treat. Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the predominant drug-resistant gram-negative pathogens associated with nosocomial infections, particularly in intensive care units (ICUs) (1). The extensive use of antibiotics in ICUs to treat infections and selective antibiotic pressure, particularly due to the intensive use of extended-spectrum cephalosporins, can lead to the selection and dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing K. pneumoniae (2). ESBLs are usually plasmid-mediated enzymes, which confer resistance to ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and other extended-spectrum cephalosporins and monobactams (1).

Resistance to antimicrobial agents is often associated with the spread of mobile genetic elements, which may also harbor virulence determinants (3). The polysaccharide capsule is the most important virulence factor in K. pneumoniae and confers a mucoid phenotype to the isolates. The plasmid gene rmpA (regulator of mucoid phenotype A) increases the extracapsular polysaccharide synthesis in K. pneumoniae and results in the hypermucoviscous phenotype (4, 5). The wcaG virulence gene encodes the capsular fucose synthesis and enhances the ability of bacteria to evade phagocytosis by macrophages (6). The rmpA gene is found on plasmids (5) and the wcaG on the transferable regions of a chromosome responsible for capsule biosynthesis (6); therefore, there is a probability of horizontal transfer of both genes. The acquisition of virulence and resistance traits may provide a strong benefit for the survival of the microorganism and may lead to severe epidemic infectious diseases (3).

Large outbreaks caused by the clonal transmission of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and/or the horizontal transfer of mobile genetic elements carrying ESBL genes have been reported, particularly in ICUs (7, 8). Epidemiological studies of the spread of K. pneumoniae depend on the availability of sensitive tests that provide sufficient discrimination between strains. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of genomic DNA is a highly discriminating typing method and has frequently been used to type ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains (8, 9). However, the comparison of isolates by PFGE encounters several limitations, including the cost of the special equipment needed and the poor reproducibility between laboratories (10). Newer molecular typing methods are commonly used, and have been proven useful for epidemiological studies (11-13). MLVA (multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis) is a PCR-based typing method that involves the analysis of variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) sequences. VNTRs are repeated sequences that vary in copy numbers even among highly related bacterial strains. The analysis of multiple VNTRs enables high-resolution genotyping. For a selected set of tandem repeats, the comparison of copy numbers between bacterial strains can provide insights into relationships between strains (12). Turton et al. described a nine-locus MLVA scheme with high discriminatory power for typing of K. pneumoniae (14, 15). This is the most commonly used MLVA scheme for typing of K. pneumoniae to date (15-18).

2. Objectives

In the present study, we investigated the presence of ESBLs and the rmpA and wcaG virulence genes in K. pneumoniae isolated from patients admitted to the ICUs of a tertiary care hospital in Tehran, Iran. Furthermore, the epidemiological relationships between ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae were studied by the MLVA method.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

A total number of 85 K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from different clinical specimens of patients admitted to the ICUs of a hospital in the southwest of Tehran, Iran. This hospital is a 420-bed teaching tertiary and referral poison treatment center with a nearly annual average of 20000 admissions and outpatient visits. The isolates were identified using biochemical tests, including triple-sugar-iron, urease, Voges-Proskauer, methyl-red, citrate utilization, indole production, and motility (19).

Antibiotic susceptibility was determined using the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Merck, Germany) as recommended by the 2016 Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) (20). Susceptibility was tested toward 14 antibiotics (Mast, UK): cefotaxime (Ctx, 30 μg), ceftriaxone (Cro, 30 μg), ceftazidime (Caz, 30 μg), imipenem (Ipm, 10 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Aug, 30 μg), aztreonam (Atm, 30 μg), ciprofloxacin (Cip, 5 μg), tobramycin (Tn, 10 μg), tetracycline (T, 30 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Ts, 25), gentamicin (Gm, 10 μg), cefepime (Cpm, 30 μg), cefoxitin (Fox, 30 μg), and amikacin (Ak, 30 μg). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain.

3.2. Phenotypic Detection of ESBL

The isolates with reduced-susceptibility to any of the tested third-generation cephalosporins (ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime) were analyzed by the combination disk method using ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), and cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg) according to the CLSI guidelines (20). The inoculum and incubation conditions were the same as those for the disk diffusion. ESBL production was confirmed if inhibitory zones of the disks with clavulanic acid were ≥ 5 mm larger than the zones without the inhibitor. K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 was used as an ESBL positive control and E. coli ATCC 25922 as a negative control.

3.3. DNA Extraction and Detection of Virulence Genes

The presence of rmpA and wcaG genes was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Genomic DNA was prepared by the freeze-thaw method and used as the template for PCR reactions. Briefly, overnight broth cultures of the isolates were centrifuged and Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer was added to the pellets. The suspensions were boiled at 100ºC for 10 min and then immediately placed on ice for 5 min. After three cycles of freezing/thawing, the tubes were centrifuged and the supernatants were stored at -20ºC as DNA templates.

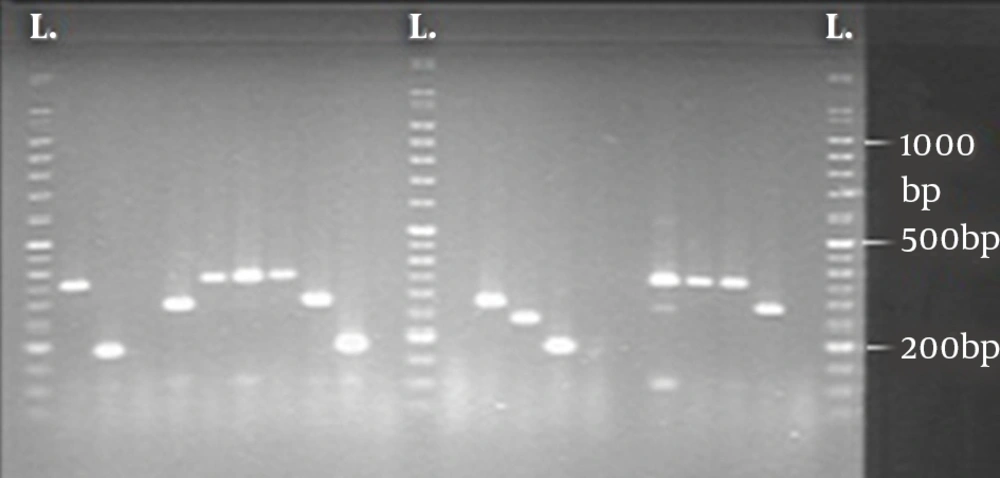

Amplification was performed as a duplex-PCR on Gene Amp PCR System PTC-1148 (Biorad, USA) using published primer pairs for rmpA: 5’-ACTGGGCTACCTCTGCTTCA-3’, 5’-CTTGCATGAGCCATCTTTCA-3’ (amplicon size: 516 bp) (21) and wcaG: 5’-GGTTGGKTCAGCAATCGTA-3’, 5’-ACTATTCCGCCAACTTTTGC-3’ (amplicon size: 169 bp) (14). PCRs were performed in a volume of 25 µL containing 1X PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 µM of each primer, 200 µM each dNTP, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, Germany), and 3 µL of DNA extract. Cycling conditions included initial denaturation at 94ºC for 5 min, 35 subsequent cycles of 1 min at 94ºC, 1 min at 54°C, and 1 min at 72°C with a final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gels in 1X TAE (Tris-Acetate-EDTA) buffer. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and the PCR products were visualized under UV light.

3.4. Molecular Typing

The ESBL-positive isolates were typed by the MLVA method. The primers targeting the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of nine VNTR loci (A, E, H, J, K, D, N1, N2, and N4) were used for amplification (Table 1) (14, 15). PCRs were performed in a total reaction volume of 25 µL containing 1X PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 µM of each primer, 200 µM each dNTP, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, Germany), and 3 µL of DNA extract. Thermocycler conditions were 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 52°C for 1 min (except loci H, E, and J for which the annealing temperature was 55°C), extension at 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The amplified products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel in 0.5X TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) buffer and run at 8 V/cm for 5 h. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide for 15 to 30 min, then rinsed with water, and visualized under UV light.

| VNTR Locus, Primer Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Period Size (bp) | Size of Flanking Sequence (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| D | 14 | 119 |

| GCAGGTCTCGTCTTCATTCC | ||

| TGACCATCGAAGAGGCG | ||

| K | 118 | 151 |

| GAGCTGGCGGCTGGAATA | ||

| GCAATCTGCCCGGAAATA | ||

| A | 140 | 129 |

| AGCGTATCTGCCATTGCC | ||

| CAGCATGGCCAGTTTGTC | ||

| E | 118 | 79 |

| CCAAATCCGGGTATTTATCG | ||

| TTCGATACCCATCCGGAAG | ||

| H | 124 | 134 |

| ATGACCAAGGAAGAACCCG | ||

| CTTTACCTGGCATGCGAACG | ||

| J | 124 | 118 |

| ACCGGATTAAGCGCTATTCC | ||

| TTCCTCGCCCACGGATAG | ||

| N1 | 116 | 107 |

| CATCAGGTGCAAGATTCCA | ||

| TGAGCGATTGCTGGCCTA | ||

| N2 | 57 | 109 |

| GATGCGGCAAGCACCAC | ||

| ACGCCCTGACCATTATGC | ||

| N4 | 67 | 119 |

| GTGCGGTGATTGTGATGG | ||

| CTGACAACGTCGATGTGG |

Primer Sequences for Amplification of VNTR Loci and Their Corresponding Period and Flanking Sequence Sizes in K. pneumoniae MGH 78578

The size of each PCR product was estimated by comparison with a size ladder. Amplicon sizes were converted into repeat numbers. Repeat numbers were then rounded up or down as appropriate and were recorded in the order of loci A, E, H, J, K, D, N1, N2, and N4, giving the VNTR profile.

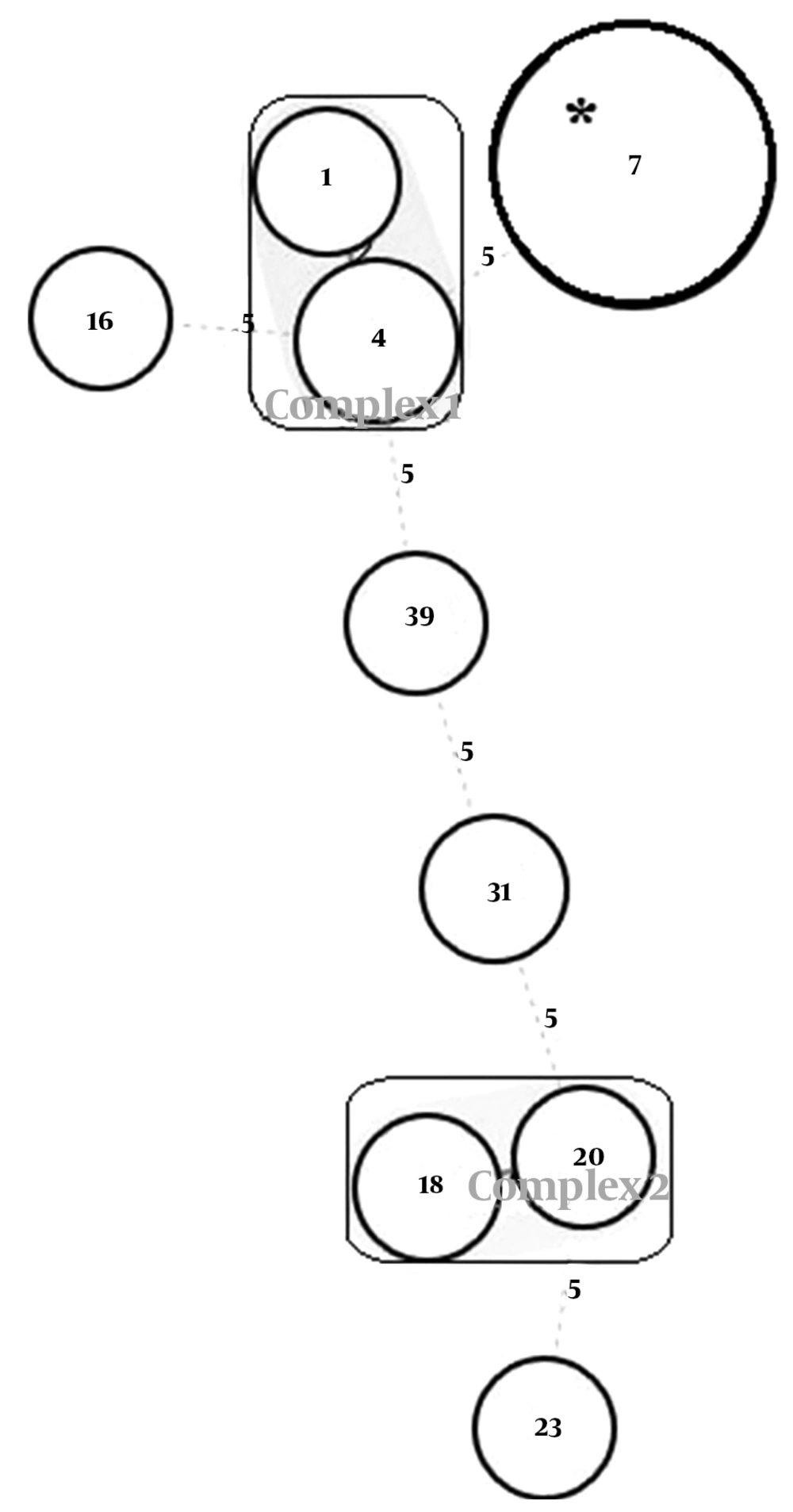

A minimum spanning tree (MST) was constructed based on allelic profiles of the strains using the online tool available at http://mlvaplus.net. A new genotype number was given when one difference was observed at any VNTR. Clones were designated as a group of isolates with indistinguishable VNTR profiles. Clonal complexes were defined as groups of isolates for which the genotypes did not differ in more than two VNTR loci (22).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and a P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The employed statistical software was SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA). The discriminatory power of MLVA was determined by Simpson’s index of diversity using a freely available online tool comparing partitions available at http://Darwin.phyloviz.net/ComparingPartitions.

4. Results

A total number of 85 K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from different clinical specimens of ICU patients in a tertiary hospital. Of the 85 isolates, 71 (83.5%) were obtained from tracheal secretions and 14 (16.5%) from urine. Twenty-nine isolates (34.1%) were from females and 56 (65.9%) from males. The analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility profile showed that all isolates, but one, were susceptible to imipenem (98.8%). Of the 85 isolates, 83 were susceptible to cefoxitin (97.6%), 72 to tetracycline (84.7%), 49 to amikacin (57.6%), 40 to gentamicin (47%), 38 to aztreonam and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (44.7%, each), 37 to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime, and tobramycin (43.5%, each), 36 to ciprofloxacin (42.3%), and 34 to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (40%). The combination disk method confirmed 56.5% of the isolates (48/85) as ESBL producers. Of these 48 ESBL-producing isolates, 45 (93.7%) were isolated from tracheal secretions and three (6.2%) from urine samples. The ESBL production was more prevalent in males than in females [(36/48, 75%) vs. (12/48, 25%), respectively].

Of the 85 isolates, the rmpA and wcaG genes were detected in 45 isolates (52.9%); rmpA was detected in seven (8.2%) and wcaG in 40 (47%) isolates. Two isolates featured both virulence genes. The prevalence of rmpA was one in the 48 ESBL-producing isolates and six in the 37 ESBL-negative isolates. There was a significant relationship between the presence of wcaG and production of ESBL (P < 0.05). The 48 ESBL-positive isolates showed a higher prevalence of wcaG compared to the 37 ESBL-negative isolates (34 vs. 6, respectively; P < 0.001).

4.1. MLVA Assay

Using any band difference in a profile to designate MLVA types, the analysis revealed nine MLVA types among the 48 ESBL-producing isolates. The discriminatory power of MLVA was 0.520 (Simpson’s diversity index) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.351 - 0.689. The MLVA assay setup for two VNTR loci is shown in Figure 1.

To examine the relatedness among the identified MLVA types, an MST analysis was performed based on the categorical datasets (Figure 2). Two clonal complexes and five singletons were identified. Complex 1 was composed of two MLVA types 1 and 4, and contained two and five isolates, respectively. These types showed the same virulence gene profile as rmpA (-)wcaG (-) and the similarity between the two types was above 70%. Complex 2 was composed of two MLVA types 20 and 18, and contained one and two isolates, respectively. These types also showed the same virulence gene profile as rmpA (-)wcaG (-) and the similarity between the two types was above 70%. The largest clone (marked with an asterisk) contained the largest number of strains (n = 33). All of these 33 isolates were rmpA (-)wcaG (+), shared the same VNTR profile (3, 5, 2, 8, 0.5, 1, 4, 5, 1, MT7), and showed the same antibiotic resistance pattern. The size of some amplicons was similar to the flanking sequences; hence, the number of repeats was designated by zero. The null allele was reported when no product was detected at that locus. Some alleles were reported as half size, which may result from the presence of intermediately sized repeat units or small deletions in the flanking sequences.

Minimum spanning tree for 48 isolates of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Each circle represents a unique MLVA type and the type number was indicated within the circle; the size of the circles indicates the number of isolates. Clonal complexes were indicated by rectangles surrounding the MLVA types. Complexes were assigned if two neighboring types did not differ in more than two VNTR loci. A dotted line indicates allelic differences at five VNTR loci. The largest clone shown with an asterisk contained the largest number of strains.

The resistance profile and virulence gene contents of each MLVA type together with the number of repeats at each VNTR locus are presented in Table 2. The MT7 was the most commonly found MLVA type representing 68.7% (33/48) of the isolates (Table 2).

| MLVA Type | VNTR Profilea | rmpA | wcaG | Sample | Number of Isolates | Resistance Profileb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 3, 5, 2, 8, 0.5, 1, 4, 5, 1 | (-) | (+) | Urine | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, Ts, Gm, Cpm, Ak |

| Trachea | 32 | |||||

| 4 | 3, 3, 3, 0, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1 | (-) | (-) | Urine | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Gm, Cpm |

| Trachea | 3 | |||||

| Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Cpm | ||||

| 1 | 6, 3, 4.5, 0, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1 | (-) | (-) | Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Ipm, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Gm, Cpm, Fox, Ak |

| 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, Ts, Gm, Cpm | |||||

| 39 | -, 8, -, 1, 1, 2, 4, 1, 1 | (-) | (-) | Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Gm, Cpm |

| 16 | 3, 2, 6, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1 | (+) | (-) | Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Gm, Cpm |

| 18 | 1, 5, 3, 5.5, 2, 2, 3, 3, 1 | (-) | (-) | Urine | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Cpm, Ak |

| Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Cpm | ||||

| 20 | 4, 5, 3, 5.5, 2, 2, 2, 3, 1 | (-) | (-) | Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, Ts, Gm, Cpm |

| 31 | 2, 3, -, 5.5, 0.5, 2, 4, 3, 1 | (-) | (-) | Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Cip, Tn, T, Ts, Gm, Cpm |

| 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, Ts, Cpm | |||||

| 23 | 6, -, 4.5, 5.5, 10, 2, 2, 2, 1 | (-) | (+) | Trachea | 1 | Ctx, Cro, Caz, Aug, Atm, Cip, Tn, Gm, Cpm |

Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of 48 Isolates of ESBL-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Along with Isolates Numbers, Their Association with Sample, Virulence Genes, and Respective MLVA Type

5. Discussion

The rapidly increasing number of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates, particularly in high-risk wards such as ICUs, and the continuous influx of strains from hospital settings to the community can lead to serious problems in clinical settings and public health (1, 2). More than half of our strains from ICU patients (56.5%) were ESBL-producers, which is in agreement with other reports (23, 24).

K. pneumoniae strains with ESBL-production and virulence characteristics complicate the management of infections and might explain the persistence and spread of particular clones within and between hospitals. Virulence factors related to the capsule play important roles in the pathogenicity of K. pneumoniae infections (4, 5); for example, rmpA confers a highly mucoviscous phenotype by enhancing extracapsular polysaccharide synthesis (5) and wcaG encodes capsular fucose synthesis and enhances the capacity to escape phagocytosis by macrophages (6). The rmpA gene has been found to be located on plasmids (5) and wcaG on the transferable regions of a chromosome responsible for capsule biosynthesis (6); therefore, there is a probability of horizontal transfer of both genes. Horizontal gene transfer is probably the most important mechanism for dissemination of virulence and resistance determinants and co-selection of virulence and resistance properties in bacteria (3). We found statistically significant differences in the prevalence of the wcaG virulence genes according to the ESBL production. Several studies have shown a correlation between the production of ESBL and virulence factors; for example, ESBL-producing isolates of K. pneumoniae were shown to produce stronger biofilms, as well as to be more invasive and more resistant to the bactericidal activity of serum (25); moreover, resistance to quinolones in E. coli isolates has been associated with the loss of virulence factors (3).

The acquisition of resistance determinants by virulent strains may lead to long persistence and dissemination of microorganisms in clinical settings. With the aim of monitoring the dissemination of ESBL-producing isolates from the ICUs of our hospital, we performed a molecular MLVA typing on the 48 ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae isolates from ICU patients, based on the previously reported VNTR loci (14, 15). The MLVA data revealed the presence of a significant genetic relatedness between the isolates with the identification of nine MLVA types, possibly reflecting antibiotic selective pressure. Antibiotic selection leads to less diversity of population structure while antibiotic-free environments allow for competition and lead to diverse non-related population structure (1, 26). The ESBL-population is likely a more selected group and a more homogenous population, allowing us to detect less diversity and few MLVA types in this group, in agreement with other reports (26, 27). For example, Hertz et al. showed that the susceptible Escherichia coli population was a much more diverse group than the ESBL-producing E. coli populations (26). The majority of our strains belonged to one major clone (MLVA type 7) showing the vertical transmission of resistant isolates and low level of infection control practices in these units. Indeed, ICU patients are ideal reservoirs for the acquisition of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae, because, in these wards, patients are exposed to a large number of potential risk factors for infection by these strains (2). Some isolates did not demonstrate the clonal spread and dissemination of these strains was likely due to the transfer of mobile genetic elements (e.g. plasmids) harboring ESBL genes (26).

Several different methods have been used for genotyping of K. pneumoniae (8, 11, 12). Although, for many years, PFGE has been the excellent typing method because of its discriminatory power (28-30), the comparison of isolates by PFGE is faced with several limitations, including the cost of the special equipment needed and poor reproducibility between laboratories, making it unsuitable for comparison between laboratories (10). In contrast to PFGE, MLVA is a PCR-based typing method that requires only basic equipment and allows interlaboratory comparison of results (12). However, studies using MLVA for the typing of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae remain limited, with a few published studies (16-18, 27, 31-33). On the other hand, with the development of techniques that allow for sequencing of bacterial chromosomes in a short time and detection of more helpful repetitive targets, MLVA may indeed be a useful method for typing, particularly for laboratories with inadequate laboratory equipment.

In conclusion, this study gave insights into the relatively high prevalence of ESBLs in K. pneumoniae isolated from the ICUs and genetic backgrounds of these strains. Due to some limitations, we could not trace the clonal spread of our isolates; moreover, the origin of suspected transmission and the possibility of a common source of infection within the units or from an unidentified environmental source remained unknown. The increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing strains of K. pneumoniae worldwide and co-existence of resistance and virulence determinants will likely lead to serious potential outbreaks and generate increasing demands for rapid and simple typing techniques with high discriminatory power. The rapidity and simplicity of interpretation of MLVA make it suitable for bacterial typing, preferably for smaller diagnostic laboratories.