1. Background

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite of humans and other warm-blooded animals (1). This parasite is responsible for congenital infections and can lead to miscarriage, hydrocephalus, blindness, mental retardation, stillbirth, and spontaneous abortions (2-4). Tissue cysts remain largely inactive for the life of the host but can reactivate and cause severe disease in immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS (5, 6). None of the current drug treatments can affect tissue cysts. Due to the lack of an effective drug for toxoplasmosis, researchers strive to develop a vaccine against this disease (7).

Recent research has shown that DNA-based vaccines can draw out strong responses of Th1 type CD4+ T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. In addition, since all naturally occurring T and B cell epitopes are encoded for any protein by the DNA construct, it can induce both humoral and cellular immune responses. Hence, DNA vaccines could be a suitable option for effective protection against T. gondii infection compared to traditional vaccines (8, 9). Many reports have shown that some single antigens were successful as DNA vaccines such as SAG1, ROP8, ROP18, ROP54, GRA1, MIC3, TgCyP, and GRA6 (9-14). The most common method for the design of DNA vaccines is the selection of parasite proteins that are involved in the host cell invasion process and can stimulate an immunological response against toxoplasmosis (8).

Surface antigens like SAG1, SAG2, and SAG3 have been investigated widely in vaccine experiments (9, 15). Immunization with SAG1, SAG2A, and SAG3 has been tested in BALB/c mice and indicated to elicit Th1 cellular immune responses against all three antigens (11). One of the main surface antigens is SAG1-related sequence 3 (SRS3). It is a member of an SRS superfamily (glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-linked proteins), which is structurally related to highly immunogenic surface antigen SAG1 with the highest overall amino acid identity among surface antigens of Toxoplasma (16).

A DNA vaccine based on SAG1 can protect against fatal infection and decrease the number of cysts. Besides, SAG1 and SRS3 are members of the same gene family and share high homology. In addition, mature SRS3 and SAG1 contain 12 cysteine residues and some identical short peptides (16-18). These findings suggest that they have similar folding, common overall topology, and the same function in stimulating the host system (16, 18, 19).

Since molecular experiments are highly expensive, bioinformatics approaches are needed for further justifying before conducting any laboratory work. Nowadays, advances in the in silico computational methods have been impressive in predicting the possible antigenic determinants. The in silico approach has numerous advantages to designing a safe, effective, and widespread vaccine against infections (20-25).

2. Objectives

In the present work, we applied bioinformatics tools with the in silico approach to predict physical and chemical properties, signal peptide, a transmembrane domain, secondary and tertiary structures, and B cell and T cell epitopes. Finally, the antigenicity of the SRS3 protein was evaluated by the Vaxigen server to prove protective immunity against T. gondii in humans.

3. Methods

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties and Posttranslational Patterns and Motifs

The functions of all proteins depend on their structures that rely on physical and chemical parameters. Therefore, to create new drugs and vaccines, we need to study the chemical, classical, biological, physical, mathematical, and informatics properties of these molecules and work together in a new area known as bioinformatics. Physical and chemical properties, molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point (pI), instability index, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), and aliphatic index of the protein were analyzed by ProtParam. Motif analyses were done by PROSITE. The trans-membrane structure and subcellular location of SRS3 within eukaryotic cells were analyzed using servers listed in Table 1. Identifying the areas of signal peptides was made by signalP version 4.0 (26). Phylogenetic analysis was performed by multiple-alignment with ClustalW using GENEIOUS version 4.8.5 software.

| Server | URL | Predicted Localization |

|---|---|---|

| CELLO | http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/ | Extracellular, cytoplasmic |

| WoLF | PSORT http://wolfpsort.org/ | Extracellular |

| PSORT | II http://psort.hgc.jp/form2.html | Cytoplasmic, nuclear |

| SLPFA | http://sunflower.kuicr.kyoto-u.ac.jp/~tamura/slpfa.html | Extracellular |

| SLP-Local | http://sunflower.kuicr.kyoto-u.ac.jp/~smatsuda/slplocal.html | Extracellular |

| SherLoc2 | http://abi.inf.uni-tuebingen.de/Services/SherLoc2 | Extracellular |

Subcellular Localization Predictors and Their Results on SRS3 Sequence

3.2. Prediction of RNA Secondary Structure

The mRNA stability of the SRS3 construct and RNA secondary structure in accordance with the optimized gene were analyzed by Mfold web server at http://mfold.rna.albany.edu/?q=mfold/RNA-Folding-Form.

3.3. Prediction of Secondary and Tertiary Structures

The secondary structure of the SRS3 protein was predicted by SOPMA (27). The prediction of the tertiary structure, function, and folding of the SRS3 protein was carried out by the protein homology/analogy recognition engine (Phyre2) (28). Ligand-binding site prediction in SRS3 was done using 3DLigandSite (29). The validation of tertiary structure prediction and modeling was performed using ProSA-web (30).

3.4. Prediction of T and B Cell Epitopes for SRS3 Protein and Comparison of Antigenicity with Applied Genes in Vaccines

The T cell epitopes were predicted using several prediction online servers, such as Immune Epitope Database, SYFPEITHI, ProPred, BIMAS, SVMHC, NetMHC, EpiJen, Rankpep, NetCTL1.2.

The protein sequence of SRS3 was analyzed for the prediction of B cell epitopes using the Bioinformatics Predicted Antigenic Peptides (BPAP) system, ABCPred, Bcepred 1.0 server, and BepiPred at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/BepiPred/.

The final B and T cell predicted epitopes were evaluated using the VaxiJen 2.0 server, which is used to evaluate the final B and T cell predicted epitopes (31, 32). Moreover, Vaxijen was utilized for the antigenicity prediction of SRS3 and comparison with applied genes in vaccines.

4. Results

4.1. Physical and Chemical Characteristics Study of tSRS3 Using Protparam Program

The SRS3 protein contains 345 amino acid residues. The molecular weight of SRS3 was 35 kDa and the acidity of the protein was indicated by the pI value. Theoretical PI was 5.76. The instability index was obtained as 43.17. The Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY) and aliphatic index of the SRS3 protein were 0.140 and 83.36, respectively.

4.2. Prediction of Modification Sites

We used PROSITE to analyze the motif. We found 12 hits on the SRS3 sequence, suggesting that there will be 12 potential Posttranslational Modification (PTM) sites on the sequence. They included four N-myristoylation sites, four protein kinase C phosphorylation sites, three casein kinase II phosphorylation sites, and one N-glycosylation site.

4.3. Prediction of Trans-Membrane Structure and Sub-Cellular Localization

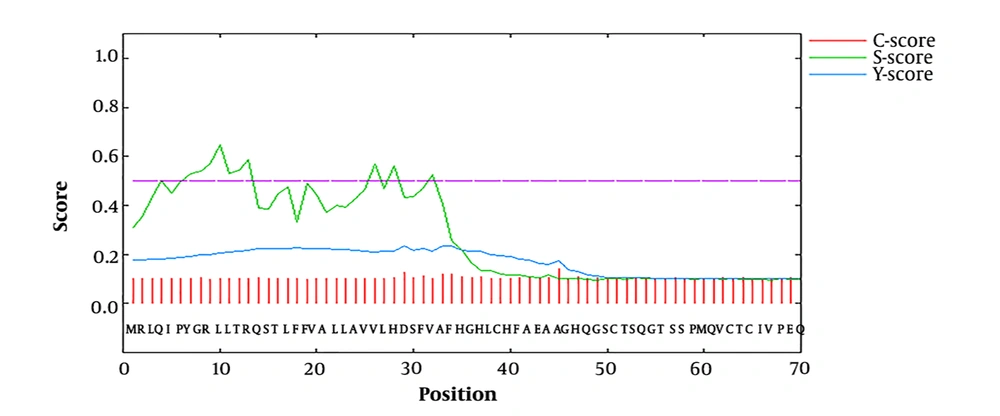

Predicting that a protein has trans-membrane segments gives more information about the function of the protein. In this study, five out of six advanced servers predicted extracellular localization for the protein sequence expressed in the eukaryotic cell program. The CELLO and PSORT II servers predicted two localizations for the hypothetical protein. The results showed that SRS3 is an outside protein (Table 1). Signal peptides and N-terminal trans-membrane helices are hydrophobic, but trans-membrane helices typically have longer hydrophobic regions. Furthermore, trans-membrane helices do not have cleavage sites; however, the cleavage-site pattern is not sufficient to distinguish the two types of sequence. Therefore, signalP (version 4.0) was used to discriminate between signal peptides and transmembrane regions. The results showed that the score of predicted signal peptide sequence was 0.329, and the cutoff was predicted to be 0.5, indicating that there was no signal peptide sequence and signal peptidase cleavage site on the amino acid sequence of SRS3 (Figure 1).

Signal peptide predicted within the SRS3 sequence. The C-score is high at the position immediately after the cleavage site. The S-score distinguishes between positions within signal peptides from those of the mature part of the proteins. The Y-score is a geometric average of the C-score and the slope of the S-score.

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of SRS3

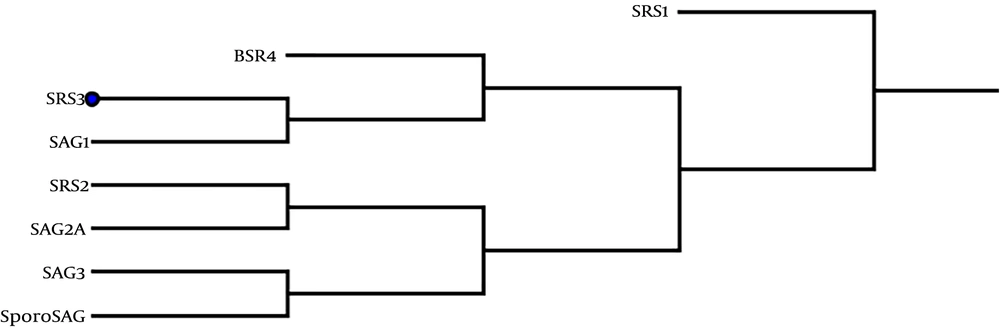

Phylogenetic analyses indicated that the SRS3 gene expressed in stage-specific tachyzoite is the closest paralog to SAG1 and BSR4, as shown in Figure 2. In mRNA stability analyses, 28 secondary structures were anticipated for optimized SRS3 mRNA, among which, a model with ΔG = -248.60 kcal/mol possessed the best-predicted stability. The value of the total ΔG of the two base pairs was -0.70 kcal/mol. Among the 28 models, just two models formed a single-stranded structure at the first 20 nucleotides of the 5’ end. The calculated ΔG of these two models was -247.50 and -247.70 kcal/mol. The best structure predicted on native mRNA had ΔG of -240.30 kcal/mol.

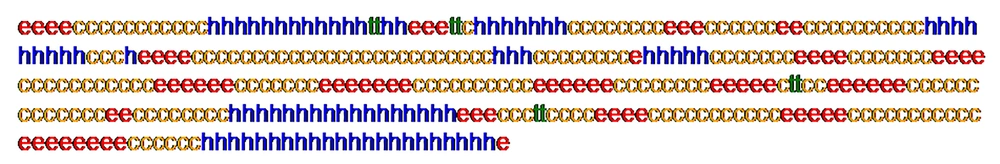

4.5. Prediction of Secondary and Tertiary Structures of tSRS3

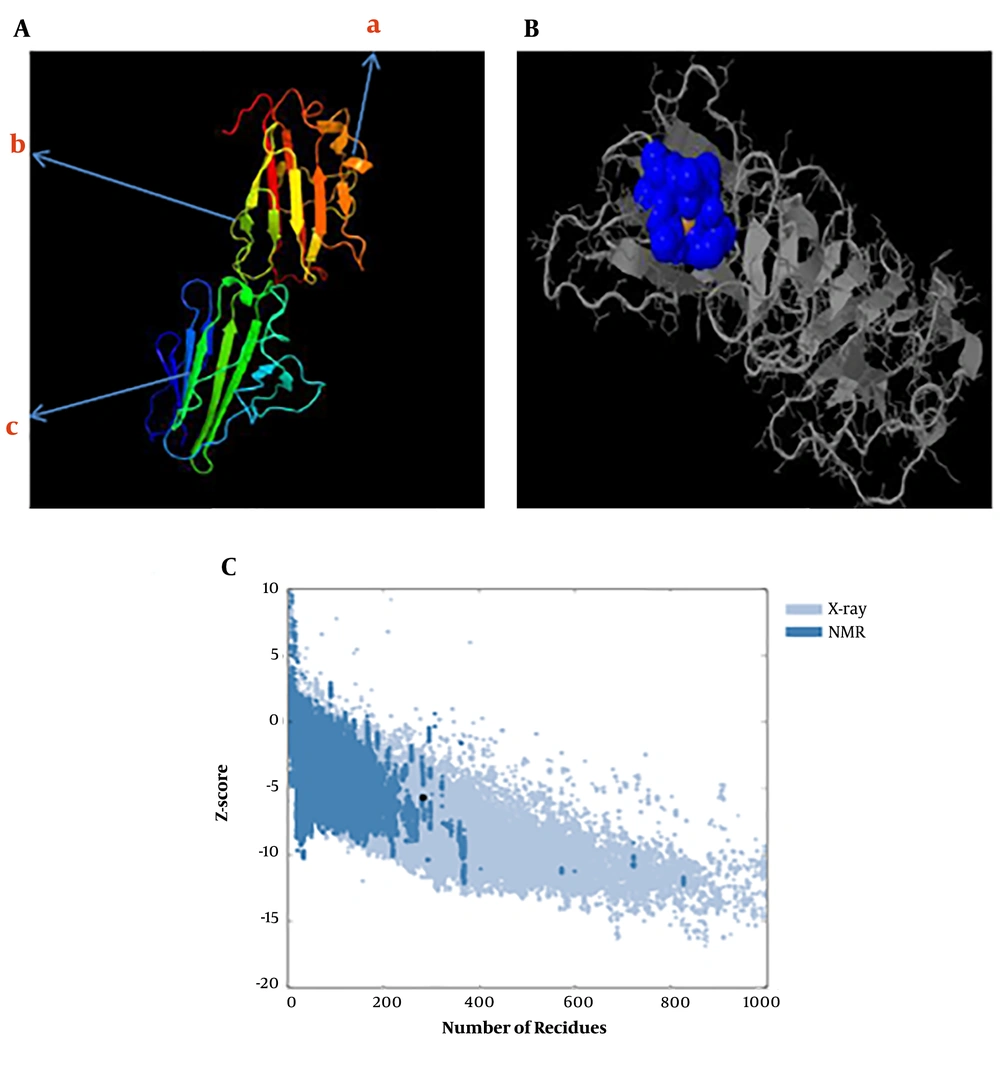

The predicted secondary structure of the tSRS3 protein is shown in Figure 3. The results revealed that tSRS3 is a coil structure-based protein. The rates of the α-helix, β-Turn, extended strand, and random coil were 13.74%, 7.22%, 31.30%, and 47.71%. The functions of proteins depend mainly on their structures. We predicted the protein fold recognition and 3D-structure related to tSRS3 using the Phyre2 server based on the protein primary structure. The results of the tertiary structure of tSRS3 showed a protein with two main domains. The confidence score (C-score) for estimating the quality of predicted models by Phyre2 was 100%, as shown in Figure 4A. The prediction of ligand-binding sites in tSRS3 was obtained using 3DLigandSite. The tertiary model of the predicted tSRS3 protein was examined using the more sensitive structure alignment program “Matching Molecular Models Obtained from Theory (MAMMOTH)”. The result identified 10 ligand clusters; among them, cluster 10 was the most significant predictor of one ligand called ZINC ION (ZN) with an average mammoth score of 30.8, as shown in Figure 4B. The residues predicted to form part of the binding site are shown in shape B (blue glob). Amino acids and their residue numbers include VAL (96), THR (97), LEU (98), PRO (99), GLY (170), CYS (171), and THR (172). Besides, ProSA was used to check 3D models of the SRS3 structure for potential errors. The z score indicates the overall model quality. The z score of -5.7 was calculated for the input structure that is within the range of scores generally found for native proteins of similar size, as shown in Figure 4C.

A, The tertiary structure prediction of SRS3 by Phyre2; 324 residues (98.7% of SRS3 sequences) were modeled with 100.0% confidence by the single highest scoring template (BSR4), a, α-helix; b, random coil; c, β-folded; B, ligand-binding site results for the SRS3 protein. Blue colors list amino acid residues observed in cluster 10 of the predicted binding site; C, ProSA-web z-score SRS3 protein plot. The z-score indicates overall model quality. The Z-scores of SRS3 protein chain A in PDB were determined by X-ray crystallography (Pale blue) or NMR spectroscopy (bold blue) concerning their lengths. The plot shows results with a z-score of ≤ 10. The z-score of SRS3 is -5.7 and is shown as a large dot. The value of -5.7 is in the range of native conformations.

4.6. In Silico Prediction of T Cell Epitopes for SRS3 Antigen

Several online prediction software was utilized to identify HLA-A*1101 and HLA A*0201 restricted epitopes from T. gondii SRS3 with the highest numbers (Table 2). The results of antigenicity among the outstanding epitopes of Toxoplasma antigens by Vaxijen showed that SRS3 epitopes were highly antigenic (Table 3).

| MHC-I Allele | Position | Peptide Sequences | Server | Vaxijen Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A*1101 | 167 - 175 | IVGCTQEGK | BIMAS | 1.7863 |

| HLA-A*1101 | 167 - 175 | IVGCTQEGK | ProPred-I | |

| HLA-A*1101 | 167 - 175 | IVGCTQEGK | EpiJen | |

| HLA-A*1101 | 247 - 256 | LQENCDEKY | RANKPEP | 0.985 |

| HLA-A*1101 | 269 - 277 | VSQAGTSNK | Consensus (ann/smm) | 0.5653 |

| HLA-A*1101 | 246 - 256 | PLQENCDEK | SVM | 1.1607 |

| HLA-A*1101 | 144 - 153 | DSQTVTCAY | NetCTL1.2 | 0.864 |

| HLA-A*0201 | 15 - 24 | STLFFVALLA | Consensus | 1.6329 |

| HLA-A*0201 | 16 - 23 | LFFVALLA | SVMHC | 2.0760 |

| HLA-A*0201 | 112 - 121 | GMTDPQSCV | BIMAS | 1.2069 |

| HLA-A*0201 | 179 - 188 | CLLHVTLSA | EpiJen | 0.8877 |

In Silico Prediction of CD8+ Final T Cell Epitopes Related to SRS3 Protein, Based on Their Predicted Binding Affinity to HLA-A*02 and HLA-A*03 Supertype Moleculesa

| HLA-A | Antigen | Peptide Sequences | Position | Vaxijen Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A*1101 | SAG1 | KSFKDILPK* | 224 - 232 | 0.4842 |

| HLA-A*1101 | GRA6 | AMLTAFFLR* | 164 - 172 | 1.9220 |

| HLA-A*1101 | GRA7 | RSFKDLLKK* | 134 - 142 | -0.2503 |

| HLA-A*1101 | SPA | SSAYVFSVK* | 250 - 258 | 0.8154 |

| HLA-A*1101 | SAG2C | STFWPCLLR* | 13 - 21 | 0.8148 |

| HLA-A*1101 | SAG2D | ALLEHVFIEK | 63 - 72 | 0.9153 |

| HLA-A*1101 | BSR4 | TTRFVEIFPK | 284 - 293 | 1.0332 |

| HLA-A*1101 | SAG3 | VVGHVTLNK | 80 - 88 | -0.4365 |

| HLA-A*1101 | SRS3 | IVGCTQEGK** | 167 - 175 | 1.7863 |

| HLA-A*0201 | GRA6 | FMGVLVNSL* | 29 - 37 | 1.9980 |

| HLA-A*0201 | SPA | GLAAAVVAV* | 82 - 90 | 0.5290 |

| HLA-A*0201 | GRA3 | FLVPFVVFL* | 25 - 33 | 2.2250 |

| HLA-A*0201 | SAG2C | FLSLSLLVI* | 38 - 46 | 0.7125 |

| HLA-A*0201 | SAG2D | FMIAFISCFA* | 180 - 189 | 1.1592 |

| HLA-A*0201 | SAG2x | FMIVSISLV* | 351 - 359 | 0.1095 |

| HLA-A*0201 | SAG3 | FLTDYIPGA* | 136 - 144 | 1.4166 |

| HLA-A*0201 | SRS3 | LFFVALLA** | 16 - 23 | 2.0760 |

Comparison of Antigenicity of Peptide Candidates Utilized for Screening of CD8+ T Cells with SRS3a

4.7. In Silico Prediction of B Cell Epitopes for SRS3 Antigen and Evaluation of Antigenicity

The B cell linear epitopes were predicted using BcePred, BAP, and ABCpred servers. The best epitopes were selected based on physicochemical properties of amino acids (accessibility, hydrophilicity, flexibility, polarity, exposed surface, and turns and strong antigenicity) (Table 4). In general, the final epitopes of SRS3 had BCpreds, ABCpred, BepiPred, and VaxiJen cutoff values of > 0.8, > 0.8, and > 0.5, respectively. The results of the evaluation of SRS3 protein antigenicity and comparison with Toxoplasma antigens used in DNA vaccines are shown in Table 5.

| B Cell Epitope | Prediction Server | Amino Acid Positions | Scores | Vaxijen Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRVTVSPKDPTFTLDCSSDG | BCPred | 210 | 0.998 | 1.2979 |

| VCPAGMTDPQSCVSPSGTIP | BCPred | 108 | 0.975 | 0.9927 |

| GSCTSQGTSSPMQVCTCIVP | BCPred | 49 | 0.955 | 0.8694 |

| MQPASFTTSYCPA | BCPred | 231 | 0.879 | 0.7269 |

| TGPLQENCDEKYASIL | ABCpred | 244 | 0.72 | 1.3467 |

| TLSARASSKDSQTVTC | ABCpred | 184 | 0.74 | 1.3257 |

| SLLSGDGASAVAWVGD | ABCpred | 123 | 0.69 | 1.1767 |

| PEAQKKVLVGCKASTA | ABCpred | 288 | 0.72 | 1.0681 |

| GETSNHAVVVSAEKNQ | ABCpred | 71 | 0.87 | 0.9510 |

| ELTITSSSPSSAWFLS | ABCpred | 313 | 0.73 | 0.9448 |

| GTIPFASLLSGDGASA | ABCpred | 124 | 0.77 | 0.8582 |

| TLDCSSD | BAP | 222 | High | 1.7363 |

| WWQVSQA | BAP | 266 | High | 1.6518 |

| NHAVVVSAE | BAP | 75 | High | 1.2996 |

| QKKVLVGCKASTA | BAP | 291 | High | 1.1761 |

| ASAVAWVGDE | BAP | 130 | High | 1.1352 |

| PQSCVSPSGTIPFASLLSG | BAP | 116 | High | 0.9466 |

| HFAEAAGHQGSCTSQGTSSPM | BepiPred | 40 | High | 1.084 |

| SLLSGDGASAVAWVGDEVN | BepiPred | 130 | High | 1.046 |

Final B Cell Linear Epitopes Based on Ability of Antigenicity. Antigenicity of Full-Length Protein Epitopes Was Calculated Using VaxiJen

5. Discussion

Vaccination with DNA vaccines against toxoplasmosis is more effective than other vaccines in inducing the activation and proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and eliciting specific antibodies essential to control chronic infection (9). The identification and verification of immunodominant recombinant antigens is the best way to achieve effective vaccines against toxoplasmosis (33). The development of DNA vaccines is a complicated process that needs molecular biology and immunology (34). In recent years, computational methods along with in silico studies compared to wet-lab methods have shown strong potential for the development of effective vaccines (35, 36). As a crucial step in the preparation of vaccines and antibodies, we require the necessary data for the identification of B and T cell epitopes. Therefore, in the present study, SRS3 was selected as a candidate vaccine and examined by the comprehensive analysis of bioinformatics with the in silico approach for the first time.

As known, SRS3 is one of the main surface antigens of tachyzoites that plays a key role in the process of invasion to the host cell (16, 37). Expression analysis using quantitative real-time PCR showed that the SRS3 gene was up-regulated in vivo relative to their expression levels in vitro (37). In addition, this antigen creates a very strong reactivity with IgG and IgM antibodies against Toxoplasma infection (37). The objectives of this study were to assess the antigenicity of SRS3 as a vaccine candidate and predict the B and T cell epitopes of tSRS3. Hence, to better understand the structure and function of SRS3, the basic sequence features were analyzed and the secondary and tertiary structures of SRS3 were studied. Protein post-translational modification (PTM) plays a basic role in cellular control mechanisms (38). We found 12 PTM sites in SRS3 including four N-myristoylation sites, four protein kinase C phosphorylation, three casein kinase II phosphorylation sites, and one N-glycosylation site. The subcellular localization prediction indicated that SRS3 is an extracellular protein. In addition, analysis of the signal peptide cleavage site by signal P (version 4.0) showed that SRS3 lacks signal peptides, contrary to the prediction made by Manger et al. (16). However, the nascent polypeptide related to a primary SRS3 mRNA transcript contains hydrophobic regions in N- and C-terminals that are not present in mature SRS3 proteins on the surface of T. gondii. The results of phylogenetic analyses displayed that this gene has the most conservation in the sequence of proteins to SAG1 and BSR4 among surface antigens of Toxoplasma, as shown in Figure 2.

The secondary structure of SRS3 represented that the rate of the random coil was above 47%. Thus, SRS3 is a coil structure-based protein that leads to an increased likelihood of forming an antigenic epitope. The third structure of SRS3 was carried out by homology modeling (Phyre 2), which has been widely used in many areas of structure-based analysis and showed high similarity with BSR4. Thus, SRS3 has a folding similar to BSR4 and SAG1. Therefore, SRS3 plays a functional role like SAG1 and BSR4 in invading the host cell. Ligand-binding site prediction identified one ligand called ZINC ION (ZN) with an average mammoth score of 30.8. The ideal DNA vaccine to protect against toxoplasmosis in humans should be able to elicit a protective T helper cell type 1 immune response and generate long-lived IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, the vaccine should be able to induce a strong B cell and T cell responses. Hence, the identification of the precise location of T cell and B cell epitopes in the protein is important for vaccine design and development. In a previous study, T. gondii proteins were analyzed to recognize CD8+ T cell epitopes that were based on their predicted binding affinity to HLA-A*02 and HLA-A*03 supertype molecules (39, 40). Therefore, in the present study, we used the most important computational prediction tools for the identification of T. gondii SRS3 protein HLA-A*0201 and HLA-A*1101-restricted epitopes. Several potential T cell epitopes on SRS3 were determined with high-affinity binding to HLA-A*02 and HLA-A*03 supertype molecules (Table 2). In addition, from an antigenic point of view, the comparison with the identified peptides of Toxoplasma antigens showed that the peptide of SRS3 is extremely antigenic (Table 3). The results of linear B cell epitope prediction showed 17 B-cells for the SRS3 protein (Table 4).

Vaxijen was used to select the final B and T cell predicted epitopes and evaluate SRS3 antigenicity (Table 5). The results revealed that SRS3 antigenicity could stimulate the immune system against toxoplasmosis more appropriately than did other T. gondii antigens that were used to construct a DNA vaccine (9, 10, 41-43). The results of the analysis theoretically determined that SRS3 is a potent antigen of strong antigenicity and has multiple epitopes with high antigenicity. Thus, SRS3 may be a promising immunogenic candidate for the development of DNA vaccines against toxoplasmosis.

5.1. Conclusions

In this study, we used bioinformatics methods with an in silico approach to predict protein characteristics, secondary and tertiary structures, and functions and finally confirmed the high antigenicity of SRS3 by the Vaxigen server for the first time. This study provides an appropriate basis for further studies on SRS3 in vaccine research.