1. Background

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is a live attenuated vaccine (1). It is the only available immunization (2) to prevent life-threatening tuberculosis such as meningitis and miliary tuberculosis (3). According to the World Health Organization, BCG immunization is recommended in parts of the world with tuberculosis infection incidence of more than 1% (4). It has been reported to be effective particularly when administered in the neonatal period (5). Although BCG immunization is considered harmless, an incidence of BCG infection of approximately 1:10,000 to 1:1,000,000 (4) is estimated after its injection. One of the most serious complications after BCG immunization is disseminated BCG infection, which is suggested to occur in inadvertently immunized persons with an underlying primary immunodeficiency such as Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Disease (MSMD), cellular immune defects, DiGeorge syndrome, and chronic granulomatous disease (4, 6, 7). Diagnosis of definitive disseminated BCG infection is based on systemic symptoms like fever or subfebrile status, weight loss, or stunted growth and two or more areas of involvement beyond the BCG vaccination site, in addition to identification of Mycobacterium bovis BCG strain by culture and/or standard PCR, as well as histopathologic changes with granulomatous inflammation (8). Probable disseminated BCG infection refers to the same clinical manifestations as mentioned above but the identification of M. tuberculosis complex by PCR, without the differentiation of M. bovis BCG substrain or other members of the M. tuberculosis complex and negative mycobacterial cultures, with the presence of typical histopathologic changes with granulomatous inflammation (7). Possible disseminated BCG infection indicates the above mentioned clinical manifestations with the presence of typical histopathologic changes with granulomatous inflammation but without the identification of mycobacteria by PCR and culture (7).

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study was to review the clinical manifestations and underlying primary immunodeficiencies leading to this complication in Iranian children with disseminated BCG infection.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

The study enrolled 47 patients with a diagnosis of disseminated BCG infection referring to Mofid Children Hospital and Masih Daneshvari Hospital, affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, for 12 years. The study began in January 2017 and completed in December 2018. The patients’ records were reviewed. All of these patients were healthy at birth and received BCG immunization within two days after birth according to the routine immunization program. The patients were classified as definitive disseminated BCG infection, probable disseminated BCG infection, and possible disseminated BCG infection based on their clinical features, imaging, pathology, mycobacterial isolation, and immunologic workup (7). Patients with any equivocal point in their records were invited with their parents or caregivers to an outpatient immunology clinic for further assessments. Patients with disseminated BCG infection complicating HIV infection were excluded from the study.

3.2. Study Design

The patients’ records were evaluated for clinical features and basic immunological workup. The basic immunological workup included complete blood count, serum immunoglobulin and complement levels, flowcytometric evaluation for analysis of lymphocyte subsets, and Nitroblue Tetrazolium Test (NBT). In patients with a diagnosis of disseminated BCG infection with an underlying specific primary immunodeficiency, the corresponding genes were detected. For those with normal immunological work-up, IL-12/23 and IFN-γ were investigated.

3.3. Ethical Issues

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mofid Children Hospital. Formal consent was obtained from parents or caregivers. Therefore, all children participated in this study by their caregivers’ decisions.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 19. Comparisons between quantitative data, such as age at onset of infection, were performed by measuring the mean, mode, median, and standard deviation. Nominal qualitative data, including sex and site of infection, were analyzed. The collected data are presented as tables and diagrams.

4. Results

4.1. General Considerations

We studied 47 patients with disseminated BCG infection during a 12-year period. Consanguinity was confirmed in the parents of 27 patients. A similar condition was reported in the family history of five patients (10.6% Ly) in the past. Twenty-five (53.2%) patients were male and twenty-two (46.8%) patients were female. The mean age at onset of clinical manifestations was 4.83 months (range: one to 12 months; median: 4 months; SD = 2.95). Twenty-eight (60%) patients were diagnosed with this condition within one year of vaccination.

4.2. Clinical Manifestations

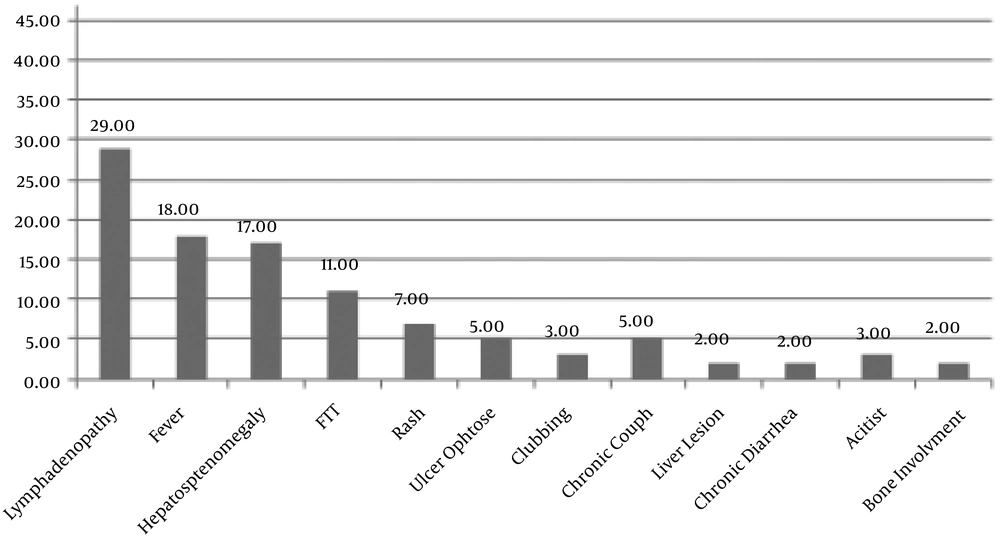

Figure 1 illustrates the common clinical manifestations with frequencies in the studied patients.

Laboratory workup revealed lymphopenia, neutropenia, and anemia in 14 (29%), 2 (4.3%), and 7 (14%) patients, respectively. Twenty-nine (61%) patients had elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR > 29 mm/h). The ESR was more than 100 mm/h in 4 (8%) patients. Twenty-seven (57%) patients showed decreased CD3, CD4, CD8 T cells, suggesting T cell immune defects. The NBT test results decreased in one (3.2%) patient. The lymphocyte transformation test was impaired in nine (19%) patients.

Collected secretions from different sites (including gastric lavage, ulcer secretions, sputum, ascites fluid, and pulmonary mass) were evaluated for mycobacterial detection by different methods (culture, PCR). A total of 21 (44.68%) patients had positive results. Gastric lavage fluid was the most common source for positive results (27.65%). The most common isolated strains were Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

The bone survey revealed osseous involvement in five (10%) patients including the femur, tibia, ankle, lumbar, and lumbosacral bones. According to the criteria suggested in the literature (7), we identified 33 (70.3%) patients with definitive disseminated BCG infection, 6 (12.7%) patients with probable disseminated BCG infection, and 8 (17%) patients with possible disseminated BCG infection.

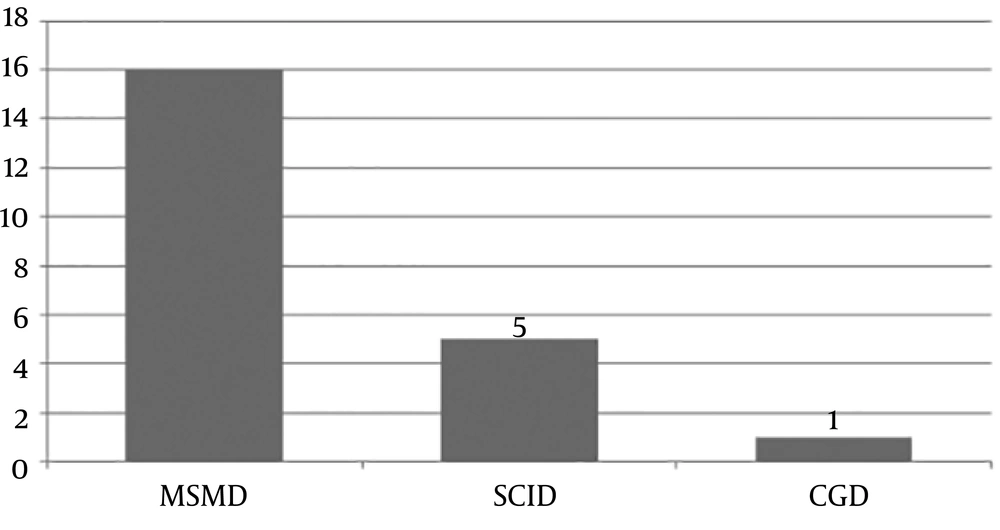

The underlying primary immunodeficiency confirmed in the patients was MSMD (69.56%), SCID (26%), and Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD; 4.3%). Among patients with MSMD, nine gene defects were identified. Figure 2 compares the frequency of underlying PIDs with known genetic defects causing disseminated BCG infection in the studied patients. Those patients not being classified in these groups may have primary immunodeficiencies with unknown novel mutations.

All the studied patients received an antituberculosis regimen consisting of four drugs for a mean duration of four years. Twelve (36%) patients did not receive any medications at the time of follow-up. Eleven (23.4%) patients also required IFN-γ injections in addition to their antituberculosis regimen. Fourteen patients died in the course of the disease of whom, eight (57.15%) were male (three patients with MSMD, one patient with SCID, and four patients with undiagnosed PIDs) and six (42.85%) were female (two patients with SCID and four patients with undiagnosed PIDs).

5. Discussion

Although the BCG vaccine is safe and widely used, there is a concern about complications that arise from this immunization. It is estimated that serious disseminated disease develops in less than one in a million cases (9) and an underlying primary immunodeficiency should be sought in these cases (10). This study was conducted to investigate the clinical features of disseminated BCG infection in Iranian children and the associated primary immunodeficiencies leading to this devastating complication.

Mycobacterial isolates are identified in clinical microbiology laboratories to the level of the M. tuberculosis complex. The combination of biochemical and growth features can strongly suggest that an isolate is BCG although none of them is definitive. In the present study, 32 patients had positive histopathological evidence of disseminated BCG infection, 23 patients had positive smears for gastric lavage fluids and ulcer secretions, and 16 patients had both positive histopathological and smear in favor of BCG infection.

Mazzucchelli et al. in 2014 reported a male dominancy of 70% in their patients with severe combined immunodeficiency and BCG-associated infection in Brazil (11). Another study performed by Al-Hajoj et al. in 2014 in Saudi Arabian children revealed a dominancy of 64.3% in male patients (12). This was true in the present study with a male dominancy of 58.6%.

Ying et al. reported the age of 3.6 months as the median age of onset of BCGosis in their study (4). Al-Hajoj et al. in 2014 reported that the majority of cases in their study with BCG vaccine-related infection were aged below six months with a median age of four months (12). The age at onset of disease in this study (predominantly < one year) was consistent with the severity of the primary immunodeficiency and was similar to prior studies (4).

Elsidig et al. in 2015 suggested lymphadenitis, both suppurative and non-suppurative, as a clinical diagnosis requiring close observation and follow-up in Saudi Arabian children (13) particularly if associated with any signs or symptoms such as systemic manifestations including fever, anemia, loss or poor weight gain, cutaneous lesions or abscesses, hepatosplenomegaly, bone tenderness or swelling (12). The most common clinical feature in patients in this study was lymphadenopathy associated with one or more of the above-mentioned manifestations. This was in line with studies performed before (13-16).

Twenty-two (46%) patients were found to have an underlying primary immunodeficiency in our study, which was in the range of previous studies (40% - 76%) (4, 17, 18). Mandal et al. (9) and Shahmohammadi et al. (15) suggested SCID as the most common underlying primary immunodeficiency associated with disseminated BCG infection (6, 8) but in the present study, MSMD (69.56%) was the most common one, like previous reports in some studies (14, 19). This discrepancy may denote the different prevalence of these primary immunodeficiencies in certain nations and parts of the world.

The mortality of our patients was similar in SCID and MSMD patients. However, in previous studies, SCID was suggested as the most common cause of death among patients with disseminated BCG infection (11, 15, 20).

We believe there are some limitations to our study. This was a retrospective study, mostly evaluating the records of patients, sometimes with insufficient data. The most potential source of bias in our study was the difference in the age range of patients in the two study centers and therefore, the underlying immunodeficiencies detected in the patients. One of these two centers provided care for pediatric patients from the neonatal period and the other one was caring for preschool children. Therefore, it was logical to find certain types of immunodeficiencies with a more severe course and fatal prognosis in the first center (e.g., patients with SCID with an earlier onset and milder forms of involvement) leading to survival to early preschool years (e.g. patients with MSMD with later onset).

5.1. Conclusions

In our country with routine BCG immunization immediately after birth and frequent consanguineous marriages, disseminated BCG infection may be a devastating complication and an important preliminary manifestation of an underlying primary immunodeficiency. Because of the wide spectrum of morbidities sometimes associated with mortality and socioeconomic burden on the health system, it is worth to take a careful medical history before BCG immunization particularly in families with a history of consanguineous marriage and death due to unknown etiology. The parents should be aware that the future siblings of the index case may be in danger and should not be given live-attenuated vaccines immediately after birth until a thorough immunological workup is completed.