1. Background

The increase of antibiotic resistance in clinical pathogens is a global health-care problem. Description of antibiotic resistance determinants at genomic level serves an important role in understanding and controlling the spread of resistant pathogens. Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) has become one of the most important bacteria, causing healthcare-associated infections. K. pneumoniae lives in natural environments and on mucosa of mammals, causing different opportunistic and hospital-acquired infections in humans. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and other types of resistance are common in K. pneumoniae strains, as reported from different parts of Iran and Asian countries. The most dangerous consequence of the so-called drug-resistant strains is infections that mainly occur in debilitating patients, which cannot be treated with routine antibiotics (1).

Aminoglycosides are used for treatment of some serious infections of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, and are usually administered in combination with other antimicrobial agents. These antibiotics attach themselves to the 30S subunit of bacterial ribosomes and interfere in the synthesis of proteins. Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycosides include production of modifying enzymes comprising aminoglycoside acetyltransferases (AACs), aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferases (ANTs) and aminoglycoside phosphotransferases (APHs), modification of the bacterial ribosome, and the decrease of drug accumulation by several mechanisms (2).

Among the resistance mechanisms mentioned above, enzymatic modification is the most common one for aminoglycoside resistance (3). ANTs and APHs are modifying enzymes affecting bisubstrate and facilitating transfer of γ-phosphate and nucleotide monophosphate from a nucleotide substrate to hydroxyl groups of aminoglycosides, respectively. However, Acetylated amino groups of AAC enzyme are derived from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) (4).

The most general modifying enzymes in K. pneumoniae are aac(6’)-I, aac(6’)-II, ant(2’’)-I and aph(3’)-VI (5). Resistance to amikacin and tobramycin is induced by aac(6’)-I, while gentamicin and tobramycin resistance is conferred by the aac(6’)-II and ant(2’’)-I genes. In addition, the aph (3’)-VI gene inactivates amikacin (6).

Modification of 16S rRNA by post-transcriptional methylation leads to the loss of affinity and high-level resistance to arbekacin, amikacin, kanamycin, tobramycin and gentamicin (7). Among more than 85 different aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, only some enzymes including ant(2’’)-I, aac(6’)-I, aac(3)-I, aac(3)-II, aac(3)-III, aac(3)-IV and aac(3)-VI appear to be the major cause of aminoglycoside resistance (8).

2. Objectives

The present present study aims to investigate aminoglycosides resistance patterns and presence of aminoglycoside modifying enzyme genes of clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates in Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates

In this cross-sectional study, 154 clinical K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from patients admitted to various wards of two hospitals (Emam Khomeini and Shahid Mostafa, as two teaching and treatment hospitals in Ilam) from April to September, 2014. The isolates were stored in a trypticase soy broth containing 15% glycerol at -20°C for further experiments. The code of ethics was not mandatory at the time of the study. The whole research work was carried out on the bacteria according to standard methods.

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Assay and Verification of ESBL-Production

Antibiotic susceptibility assay was carried out by the disk diffusion method on the Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco, Germany), based on the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (9). Aminoglycoside antibiotics including amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, netilmicin and kanamycin were used for phenotypic screening of aminoglycoside resistant isolates. The ESBL-producing isolates were verified by the double disc diffusion method. Phenotypic screening of the ESBL-producing isolates was performed with cefotaxime-clavulanic acid (30/10 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), ceftazidime-clavulanic acid (30/10 µg), and ceftazidime (30 µg) discs (Mast, England). An increase of ≥ 5 mm in the inhibition diameter zone of clavulanic acid-supplemented discs, as compared with the inhibition diameter zone of plain discs was consider as the ESBL-producer. K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 was used for the ESBL positive control.

3.3. Detection of Aminoglycoside Resistance and ESBL Genes

Aminoglycoside resistant genes (aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib, and aac(3)-Ia) and 16S rRNA methylase (armA and rmtB), as well as ESBL-producing genes (blaTEM (beta-lactamase temoneira), blaSHV (beta-lactamase sulfhydryl variable) and blaCTX-M (beta-lactamase cefotaxime)) were detected by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. To extract DNA, fresh bacterial colonies were suspended in 100 mL of sterile distilled water and boiled at 100°C for 10 min; then, they were stored at -20°C for 15 min. After centrifugation in 1000 rpm for 5 min, 3 mL of the supernatant was used for PCR assays with the primers shown in Table 1. Amplification of DNA was performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany). PCR processes and conditions are explained in Table 2.

| Gene | Primer | Amplified Size, bp | Annealing Temperature, °C | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aac(3)-Ia | F: 5’-ATGGGCATCATTCGCACA-3’ | 484 | 55 | (10) |

| R: 5’-TCTCGGCTTGAACGAATTGT-3’ | ||||

| aac(6’)-Ib | F: 5’-ATGACTGAGCATGACCTTG-3’ | 524 | 53 | (10) |

| R: 5’-AAGGGTTAGGCAACACTG-3’ | ||||

| aac(3)-IIa | F: 5’- CGGAAGGCAATAACGGAG-3’ | 749 | 55 | (11) |

| R: 5’ -TCGAACAGGTAGCACTGAG-3’ | ||||

| armA | F: 5’-AGGTTGTTTCCATTTCTGAG-3’ | 591 | 53 | (12) |

| R: 5’- TCTCTTCCATTCCCTTCTCC-3’ | ||||

| rmtB | F: 5’-CCCAAACAGACCGTAGAGGC-3’ | 585 | 56 | (12) |

| R: 5’-CTCAAACTCGGCGGGCAAGC-3’ | ||||

| blaTEM | F: 5’- ATGAGTATTCAACATTTCCGT-3’ | 861 | 53 | In this study |

| R: 5’- TTACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGA-3’ | ||||

| blaSHV | F: 5’-GGGTTATTCTTATTTGTCGC-3’ | 927 | 53 | In this study |

| R: 5’- TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTC-3’ | ||||

| blaCTX-M | F: 5’-ACGCTGTTGTTAGGAAGTG-3’in | 759 | 55 | In this study |

| R: 5’-TTGAGGCTGGGTGAAGT-3’ |

Primers Used for the PCR Detection of aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib, and aac(3)-Ia; 16S rRNA Methylases (armA and rmtB); and blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M Genes

| Number of Cycles | Cycle Name | Temperature and Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary denaturation | 94°C for 5 minutes | |

| 35 | Denaturation | 94°C for 45 seconds | |

| Annealing | aac(3)-Ia | 55°C for 30 seconds | |

| aac(6’)-Ib | 53°C for 30 seconds | ||

| aac(3)-IIa | 55°C for 30 seconds | ||

| armA | 53°C for 30 seconds | ||

| rmtB | 56°C for 30 seconds | ||

| Primary extension | 72°C for 1 minutes | ||

| 1 | Final extension | 72°C for 10 minutes |

PCR Conditions for the Detection of Aminoglycoside Genes

Electrophoresis was performed in 1.5% agarose gel, which was stained with safe-stain and visualized in a gel document system. The QIA quick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, CA, USA) was used for purification of the PCR product of the rmtB gene. Moreover, the ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) was employed for sequencing the both strands. Then, the sequences were compared with the nucleotide database in GenBank at NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/).

4. Results

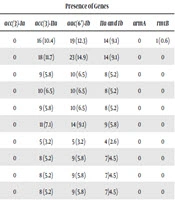

The K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from patients admitted to the intensive care unit, as well as to internal, neurosurgery, infectious diseases, neurology and general surgery wards. The isolates were obtained from different clinical specimens including urine (88.3%), trachea (4.5%), ulcer (6.5%), and sputum (0.6%), belonging to male (30.5%) and female (69.5%) patients. The susceptibility pattern showed that of the 154 isolates, 34%were resistant to aminoglycosides, 14.9% were gentamicin resistant, and 8.4%, 20.1%, 7.8%, and 9.1% were resistant to tobramycin, kanamycin, netilmicin, and amikacin, respectively; only three isolates (1.9%) were resistant to all the aminoglycoside antibiotics. Resistance to single and multiple aminoglycosides and the rate of resistance genes in phenotypically resistant strains are described in Table 3. The results indicated a high rate of kanamycin (25, 16.23%) and amikacin (13, 8.44%) resistance in the urine isolates.

| Antibiotics | Resistance Number, % | Presence of Genes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acc(3)-Ia | acc(3)-IIa | aac(6’)-Ib | IIa and Ib | armA | rmtB | ||

| GM | 23 (14.9) | 0 | 16 (10.4) | 19 (12.3) | 14 (9.1) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| K | 31 (20.1) | 0 | 18 (11.7) | 23 (14.9) | 14 (9.1) | 0 | 0 |

| AK | 14 (9.1) | 0 | 9 (5.8) | 10 (6.5) | 8 (5.2) | 0 | 0 |

| TOB | 13 (8.4) | 0 | 10 (6.5) | 10 (6.5) | 8 (5.2) | 0 | 0 |

| NET | 12 (7.8) | 0 | 9 (5.8) | 10 (6.5) | 8 (5.2) | 0 | 0 |

| GM and K | 19 (12.3) | 0 | 11 (7.1) | 14 (9.1) | 9 (5.8) | 0 | 0 |

| GM and AK | 6 (3.9) | 0 | 5 (3.2) | 5 (3.2) | 4 (2.6) | 0 | 0 |

| GM and TOB | 12 (7.8) | 0 | 8 (5.2) | 9 (5.8) | 7 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| GM and NET | 11 (7.1) | 0 | 8 (5.2) | 9 (5.8) | 7 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| GM, K, and AK | 6 (3.9) | 0 | 8 (5.2) | 9 (5.8) | 7 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| GM, K, AK, and TOB | 4 (2.6) | 0 | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| GM, K, AK, TOB, and NET | 3 (1.9) | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| K, AK, TOB, and NET | 3 (1.9) | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| K, AK, and TOB | 5 (3.2) | 0 | 4 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| K, TOB, and NET | 10 (6.5) | 0 | 8 (5.2) | 8 (5.2) | 7 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| K and AK | 13 (8.4) | 0 | 9 (5.8) | 8 (5.2) | 7 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

Phenotypic and Genotypic Patterns of K. pneumoniae Against Aminoglycoside Antibioticsa

Among the isolates, 36.4% and 31.8% were resistant to ceftazidime and cefotaxime, respectively. Moreover, 59.1% (n = 91) of the isolates were identified as ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. All the ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were checked for the ESBL genes, and 83.5% (n = 76), 52.7% (n = 48) and 26.4% (n = 24) were harbored as blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX-M, respectively. Co-existence of blaTEM-blaSHV, blaTEM-blaCTX-M and blaSHV-blaCTX-M was detected in 20.9% (n = 19), 15.4% (n = 14) and 8.8% (n = 8) of the isolates, respectively, and 6.6% (n = 6) of the isolates had all the three genes.

The results showed that the aac(3)-Ia and armA genes were absent in all the resistant isolates. Moreover, the kanamycin resistant isolates (n = 31) showed the highest prevalence of aac(6’)-Ib (n=23, 74.2%) and aac(3)-IIa (n = 18, 58.1%). Overall, 11.7% (n = 18) isolates showed resistance to the both kanamycin and gentamicin and among them, 61.1% (n = 11) had both aac(6’)-Ib and aac(3)-IIa. All the aminoglycoside resistant isolates were collected from urine, which had both the aac(6’)-Ib and aac(3)-IIa resistance genes; only one isolate with gentamicin resistance had rmtB.

5. Discussion

The outbreak of nosocomial multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria has caused severe therapeutic problems. Various drug resistance genes such as aminoglycoside, sulfonamide, beta-lactamase and carbapenemase genes have been studied in Gram-negative bacteria such as K. pneumoniae in Iran and other countries of the world (13-17). The highest antibiotic resistance rate in the present study belonged to ceftazidime whereas the lowest rate was observed for tobramycin. Phenotypically, 59.1% (n = 91) of the K. pneumoniae isolates were ESBL-producers. The prevalence of blaTEM was higher than that of blaSHV and blaCTX-M. Resistance to aminoglycosides has been attributed to the acquisition of several aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (18). Previous studies on mechanisms of aminoglycoside resistance have also indicated that aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, including aac, aph, and ant are the primary mechanisms of resistance to these antibiotics (19). In this study, the highest aminoglycosides resistance occurred in kanamycin (n = 31, 20.1%) whereas the lowest one was found in netilmicin (n = 12, 7.8%). It should be noted that because of their narrow efficiency against the substrate and low specificity, these enzymes alone cannot induce resistance to all aminoglycosides. Since some enzymes modifying gentamicin had a weak activity against amikacin (19) and amikacin was developed from kanamycin, the access of various kanamycin modifying enzymes to their target was observed at a low prevalence among the members of Enterobacteriaceae (20).

PCR analysis disclosed that susceptible isolates had no resistance genes. In our study, 9.1% (n = 14) of the isolates were amikacin resistant. Among the isolates, nine contained the aac(3)-IIa gene, 10 contained the aac(6’)-Ib gene, and eight had the both genes (Table 3). However, four amikacin resistant isolates had no aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, as observed in the study. Therefore, it is needed to evaluate other aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes in future. The prevalence rate of amikacin resistance within ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates from the United States, Latin America, Europe, the Western Pacific region and Canada was found to be 11.1%, 66.1%, 54.2%, 37.7% and 5.6%, respectively (21).

The aac(3)-IIa gene was primarily detected in R plasmids, delegating the aac(3)-II pattern phenotype (22). Reportedly, the rate of this gene is 85% in the aac(3)-II pattern phenotype (8, 23). The aac(3)-VI resistance pattern can cause resistance to gentamicin (3, 22). The aac(3)-VI gene is primarily detected from a conjugative plasmid in Enterobacter cloacae. This gene is rarely observed in clinical isolates (3). It can be deduced that there is 50% similarity between the amino acid sequences of the aac(3)-VI and aac(3)-IIa genes (24). According to Chinese reports, in pediatric patients with clinical isolates, including qnr and aac(6')-Ib-cr, and ESBL-encoding genes were transferred together in ESBL- or AmpC-producing Escherichia coli. Since the identification of the armA gene in K. pneumoniae BM4536 strains from France in 2000 and the primary identification of the rmtB gene in S. marcescens S-95 strains from Japan in 2002, the two mentioned genes have been detected in P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae in many areas (25-30).

In our study, the overall rate of 16S rRNA methylase genes (armA and rmtB) in the clinical K. pneumoniae isolates was 0% and 0.6%, respectively, which was lower than the previously declared rates in a Taiwanese research (0.9% and 0.3%) and a research conducted in Shanghai, China (3% and 1%) (29, 31). Our data, in agreement with other studies reporting on Enterobacteriaceae, showed that rmtB could be more prevalent than armA. Indeed, the rmtB gene is the most prevalent 16S rRNA methylase gene among Enterobacteriaceae isolates. In the present study, armA was not detected, which is compatible with other studies (29, 32). This report further highlights the low dissemination of 16S rRNA methylase genes among K. pneumoniae.

In Argentina, the 16S rRNA methyltransferase gene rmtD2 was observed in 0.7% of Enterobacteriaceae. The incidence rate of the rmtD2 gene was 13.3% in Citrobacter spp. and 9.3% in Enterobacter spp. Moreover, a correlation was reported between the presence of rmtD2 and resistance to both amikacin and gentamicin (33).

In the study of Miro et al., among 330 various Enterobacteriaceae, 26.3%, 18%, 16.9%, 3.6% and 1.5% were resistant to kanamycin, gentamicin, tobramycin, netilmicin and amikacin, respectively, and 12.4% and 4.2% had aac(3)-IIa and aac(6’)-Ib genes, respectively. Their results are consistent with our findings, showing the highest resistance to kanamycin (10). Furthermore, the study of carbapenemase and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (51 E. coli and 36 K. pneumoniae) isolates in Tunisian and Libyan hospitals showed that ESBL-producers and aminoglycoside resistance were 66.6% and > 60%, respectively, which are higher than those in our study (11). In Malaysia, 93 multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates had 91.3% and 67.7% of blaCTX-M15 and aacC2 genes, respectively (12).

In China, from 162 aminoglycoside resistant isolates of K. pneumoniae, 47.5% (n = 77) were ESBL-positive, and 30.2% (n = 49), 19.7% (n = 32), 11.1% (n = 18), and 6.2% (n = 10) had aac(3)-IIa, aac(6)-Ib, armA and rmtB genes, respectively. However, in the present study, the rate of 16S rRNA methylase genes (armA and rmtB) were higher (34). In another study, 17%, 37%, 68%, 53%, and 42% of K. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, kanamycin, gentamicin and tobramycin, respectively. In addition, 66%, 11% and 13% of the isolates had blaSHV, rmtB, and rmtC, respectively. This is consistent with our results, showing the highest resistance to kanamycin; however, the range of blaSHV and rmtB was reported to be higher than that in our study (35).

The present study revealed the high prevalence of aac(3)-IIa and aac(6’)-Ib genes and the low prevalence of aac(3)-Ia and 16S rRNA methylase genes (armA and rmtB) among ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates in Iran. Moreover, the rate of 16srRNA methylase genes was low in K. pneumoniae.