1. Background

A. baumannii is a non-motile, oxidase-negative, aerobic, and non-fermenting Gram-negative coccobacillus that is mostly seen among hospitalized patients, especially in the intensive care units (ICU) (1). This organism creates a wide range of infections such as ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), pneumonia, endocarditis, skin infections, bacteremia, wound infection, urinary tract infection, and meningitis (2). In different species of Acinetobacter, the acquisition and dissemination of a drug-resistant determinant in community and hospitals are greatly facilitated by horizontal gene transfer of genetic mobile elements such as transposons, plasmids, and integrons. Among these genetic mobile elements, integrons are important because of their capacity for expressing and carrying resistance genes (3). Recently, due to the high use of antibiotics, extensive antibiotic resistant and multidrug-resistant A. baumannii (XDR-AB, and MDR-AB) have emerged as a major problem worldwide (1).

The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, as well as the transmission of strains among patients, created a selective pressure that led to the emerging of MDR-AB (4). The most important challenge for clinical microbiologists and physicians is the management of MDR Acinetobacter spp. infections. Ability to survive in clinical settings makes it a common agent for healthcare-associated infections which leads to multiple outbreaks. Spectrums of infections due to MDR Acinetobacter spp. contain pneumonia, UTI, bacteremia, wound infection, and meningitis. A. baumannii is intrinsically resistant to antibiotic agents, which is due to the expression of active efflux pump systems; the low expression of outer membrane porins; having a resistance island, which contains a cluster of genes encoding antibiotic; and heavy metal resistance, which causes resistance to ammonium-based disinfectants (5).

A. baumannii shows several mechanisms to resist multiple antibiotic classes, including the production of antibiotic degradation/modification enzymes, decreased permeability, active drug efflux pumps, modification in drug targets, and biofilm formation (6). It is also difficult to control A. baumannii because it can survive in hospital settings for a long time. The potential of A. baumannii to demonstrate multiple antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation may be involved in the ability to survive in the environment (7). Biofilm formation on all surfaces is a good strategy for increasing the chances of bacterial survival in stressful conditions following environmental conditions or antibiotic treatment (6, 7). Increasing the synthesis of exopolysaccharides and also the development of drug resistance are sometimes associated with biofilm production (8). Many factors are involved in the formation of biofilms, including outer membrane protein A (OmpA), biofilm-associated protein (Bap), beta-lactamase PER-1, iron uptake mechanism, and the CsuA/BABCDE chaperone-usher pili assembly system (9). Some surface proteins such as ompA, blaPER-1, and Bap, in addition to being involved in biofilm formation, are also involved in the bacterial attachment to human epithelial cells and abiotic surfaces (10).

The expression of the CsuA/BABCDE chaperon-usher complex is needed for the assembly and production of pili contributing to adhesion to abiotic surfaces (11). It has been shown that inactivation of the csuE gene inhibits the production of pili as well as biofilm formation (12). The expression of csu operon is controlled by a two-component regulatory system, including a response regulator encoded by bfmR and a sensor kinase encoded by bfmS. Translational and transcriptional analyses show that the inactivation of bfmR prevents the expression of this operon and the consequent inactivation of both pili production and biofilm formation (13). In addition, the blaPER-1 gene is also associated with increased biofilm formation and increased bacterial attachment to the abiotic surfaces and human epithelial cells (10).

2. Objectives

Because of the importance of genes blaPER-1 and csuE in cell adhesiveness and pili production, as well as the formation of biofilms and ultimately antibiotic resistance, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of these genes in the clinical strains of Isfahan and the association of these genes with biofilm production.

3. Methods

3.1. Collection and Identification of Bacterial Isolates

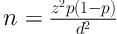

In this cross-sectional study, based on Equation 1

where d: 0.09 , p: 0.533, and z: 1.96 (1), one hundred and eighteen A. baumannii isolates were collected from October 2017 to June 2018 at three educational hospitals affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences Isfahan, Iran. The isolates were collected from different clinical samples such as sputum, endotracheal aspirates, urine, blood, aspirates, intravenous catheters, wound, tissues and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of the patients hospitalized to different wards in educational hospitals (Al-Zahra, Imam Mousa Kazem, and Shariati) in Isfahan, Iran. The samples were cultured on standard laboratory media such as MacConkey agar and blood agar (Merck, Germany) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Primary identification was performed by conventional biochemical tests and was also confirmed by the PCR method for blaOXA-51 gene as previously explained (14).

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests

3.2.1. Disk Diffusion

The antimicrobial Susceptibility testing was performed based on Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method according to Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute guidelines (CLSI) (15) against meropenem (10 µg), imipenem (10 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), doxycycline (30 µg), piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 µg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg), cefepime (30 µg), amikacin (30 mg), and tetracycline (30 mg) disks (Mast Group Co, UK). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain for antibiotic disks in susceptibility testing (15).

3.2.2. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

A microbroth dilution assay was used to determine MICs of imipenem and colistin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) according to CLSI (15). Serial concentrations of imipenem and colistin were used (from 256 to 0.25 µg/mL). The last well where turbidity was not observed was considered MIC. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain.

3.3. Biofilm Production Assay

The A. baumannii isolates were analyzed for their ability to biofilm production using microtiter dish biofilm formation assay with 0.1% crystal violet according to the instructions described (16). The absorbance of each well was measured at 560 nm using an ELISA reader. For each isolate, the assay was repeated at least three times. Uninoculated wells containing media were used as a control (16). Based on the optical density of the samples (ODi) and also on the average of the optical density of the negative control (ODc), the isolates were classified as follow: if ODi < ODc, the bacteria were non-adherent; if ODc < ODi ≤ 2xODc, the bacteria were weakly adherent; if 2xODc < ODi ≤ 4xODc, the bacteria were moderately adherent; and if 4xODc < ODi, the bacteria were strongly adherent (16).

3.4. Detection of Biofilm-Related Genes (csuE, bap, and blaPER-1)

The bacterial genome was extracted using boiling method, as described previously (17). The PCR assays were performed by the primers shown in Table 1 to determine the presence of csuE, bap, and blaPER-1 genes. The conditions for PCR amplification were initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 seconds, primer annealing at 59°C for blaPER-1, 48°C for csuE and 57°C for bap for 45 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 50 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 6 minutes. P. aeroginosa containing blaPER-1 received from Pasteur Institute, France, was used as the positive control.

The Primers Used in This Study for Detection of bla OXA-51 Gene and Biofilm-Related Genes

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using software IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., USA). The association between genes involved in biofilm formation and also the amount of biofilm formation with antibiotic resistance phenotypes of A. baumannii was evaluated by chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. The total frequencies of biofilm-related genes were measured in isolates and their relationship to biofilm formation was analyzed using multinomial logistic regression test. The analysis was performed with a confidence level of 95%. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

During the 9-month period of study 118 clinical isolates of A. baumannii were collected. Overall, 79 (66.9%) isolates were obtained from male and 39 (33.1%) from female samples. Sixty-three A. baumannii isolates (53.4%) were recovered from tracheal aspirate, followed by 13 (11.0%) from wounds, 7 (5.9%) from CSF, 9 (7.6%) from sputum, 4 (3.4%) from blood, 2 (1.7%) from catheters, and 20 (17.1%) from other samples.

Antibiotic resistance was severe among the isolates. One hundred and nine (92.4%) of isolates were susceptible to colistin and all isolates were resistant to imipenem. Among 118 isolates, 16.1% (19/118) of A. baumannii isolates were identified as XDR and 83.9% (99/118) of isolates were MDR. Table 2 shows an antibiotic resistance pattern of the A. baumannii isolates. The MIC of A. baumannii isolates is shown in Table 2. The range of MIC for colistin in isolates was ranged from 0.25 to 8 mg/mL and 92.4% of them were susceptible to colistin. According to results, 100% of isolates were resistant to imipenem. The majority of imipenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates exhibited a MIC ≥ 256 µg/mL (Table 3).

| Antibiotic | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meropenem | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 117 (99.2) |

| Imipenem | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 118 (100) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 117 (99.2) |

| Ceftazidime | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 116 (98.3) |

| Gentamicin | 5 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 113 (95.8) |

| Tetracycline | 7 (5.9) | 20 (16.9) | 91 (77.2) |

| Doxycycline | 5 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 113 (95.8) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 117 (99.2) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 116 (98.3) |

| Cefepime | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 117 (99.2) |

| Amikacin | 9 (7.6) | 11 (9.3) | 98 (83.1) |

Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of the Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates (N = 118)a

| Antibiotic | Breakpoint, µg/mL | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin | Susceptible ≤ 2, resistant ≥ 4 | 109 (92.4) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (7.6) |

| Imipenem | Susceptible ≤ 2, resistant ≥ 8 | 118 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

The MIC of A. baumannii Isolates Against Colistin and Imipenema

The majority of isolates were able to form varying degrees of biofilm. The mean optical densities for isolates were 0.306 ± 0.018 (ranged from 0.052 to 1.046). Based on the results, biofilm formation capabilities of the isolates were classified as non-biofilm, weak, moderate, and strong biofilm producer that 32 (27.1%), 33 (28.0%), 37 (31.4%), and 16 (13.6%) isolates had non-biofilm, weak, moderate, and strong-adherence activity in the microplate assay, respectively. In all (100%) isolates, the blaOXA-51 gene was detected and confirmed the A. baumannii. In the 118 isolates, the detection rates of bap, csuE, and bla-PER1 were 70.3%, 93.2%, and 54.2%, respectively (Table 4). The mean for biofilm biomass in bap, csuE, and blaPER-1 positive isolates were 0.356 ± 0.210, 0.308 ± 0.198, and 0.359 ± 0.234, respectively.

| Biofilm Intensity | Biofilm-Related Genes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| bap | blaPER-1 | csuE | |

| Strong (n = 16) | 16 | 12 | 14 |

| Moderate (n = 37) | 36 | 29 | 36 |

| Weak (n = 33) | 31 | 14 | 29 |

| Non-biofilm (n = 32) | 0 | 9 | 31 |

| Total (n = 118) | 83 | 64 | 110 |

Biofilm-Related Gene Expression and Biofilm Intensity in Clinical Isolates of A. baumannii

Statistical analysis revealed a significant correlation between the frequency of blaPER-1 positive strains and biofilm formation in all isolates (P < 0.05). The results showed that 70.3% (83 cases) of A. baumannii isolates encoded bap gene and 93.2% of the isolates encoded csuE gene that the presence of bap gene is associated with biofilm formation (P ≤ 0.001), but no significant correlation was seen between the presence of csuE gene and biofilm formation. There was a significant association between biofilm-forming ability and amikacin resistance (P < 0.05).

5. Discussion

A. baumannii is an opportunistic pathogen that can colonize the skin, oral cavities, respiratory tract, conjunctiva, urinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract. Nosocomial infections of this pathogen are generally transmitted directly from health-care workers or via environmental surfaces to patients because of the ability of this organism to survive in the environment for a long time (20, 21). A. baumannii colonization has been reported commonly from ICU and surgical wards, where most of nosocomial infections occurred (22). In order to effectively control the infection in hospitals, particularly in ICU, the main parameters should be evaluated to provide useful and practical approaches that they could be used as a strategic plan for infection control committees. Physicians should also use this information to achieve effective therapies, combat antibiotic resistance, reduce medical costs, and reduce mortality. For this purpose, the current study was designed to evaluate different parameters (i.e. the ability of biofilm production, the frequency of biofilm-related genes, etc.) and considering the importance of bap, blaPER-1, and csuE genes in cell adhesion and contribution to the formation of pili, respectively. In addition, biofilm production and resistance to antimicrobial drugs were also investigated.

In this study, we observed that A. baumannii isolates were resistant to drugs commonly used to treat A. baumannii. Moreover, 16.1% of isolates were XDR and 83.9% were MDR. Antibiogram and MIC tests showed that the resistance of isolates to many antibiotics was more than 90% and they were just sensitive against colistin that out of 118 isolates, 9 isolates were resistant to colistin, and since there are no new drugs for this infection and as an alternative to existing drugs, as well as there is no vaccine against this infection, the only way to eliminate the effects of infection is to control their spread. In our study, the prevalence of colistin-resistant A. baumannii was 7.6%, while in previous studies it was 0% (23), 6% (24), and 12% (25). Although resistance to colistin has been reported in our study, this drug is the most effective and best option for treating this infection.

Among various virulence factors, the ability to form biofilm is one of the most important factors involved in the pathogenicity of A. baumannii (12). The present study proved that 72.9% of isolates were able to form biofilms (in varying degrees), which had a lower rate than other studies. In a study conducted by Bardbari et al. in Hamadan, almost 100% of isolates were able to form biofilms (1). Also, in a study conducted by Vijayakumar et al. in India, all isolates were also able to form biofilms (12). The frequency of genes involved in biofilm formation was largely similar to other studies (1, 19, 26, 27).

Most of Acinetobacter isolates encoded bap gene. The presence of this gene in isolates was significantly associated with the ability of biofilm formation (P < 0.001). Azizi et al. (19) and Sung et al. (28) showed that the ability to form a biofilm in A. baumannii isolates carrying the bap gene was significantly different from isolates that lack this gene. Our observations also confirmed the important role of bap gene in biofilm formation. In a study by Bardbari et al. in 2016 in Hamadan (1), there was no significant relationship between biofilm formation and blaPER-1 gene, while there was a positive correlation between the existence of this gene and biofilm formation in the present study (P < 0.05).

The data from our study is used to improve the disinfection methods for controlling infectious diseases. Therefore, expanding the knowledge of the mechanisms that lead to biofilm production as well as the development of antibiotic resistance will allow us to treat or control biofilm-related infections. The limitation of our study was that only clinical specimens were used and environmental samples were not studied, which may affect the outcome of the observation. In this study, the genes ompA and abaI that could be involved in biofilm formation were not investigated. Therefore, the relationship between the presence of these genes and the rate of biofilm formation is suggested for future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

Most isolates were able to form biofilms. There was a significant correlation between the presence of bap and blaPER-1 genes in the A. baumannii isolates and the ability to form biofilms. This research provides information on the characteristics of clinical isolates, such as resistance to antibiotic agents and biofilm formation that improve our understanding of how to control the infection.