1. Introduction

Aspergillus is the most common mold infection, which is found ubiquitously, e.g., in the soil, air, and water. Airway inhalation of Aspergillus spores may lead to localized infection in the lungs, sinuses, and can spread to other organs, such as kidneys or brain in an immunocompetent person. Aspergillus species are the most common causes of invasive infections associated with high morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised persons (1). Invasive aspergillosis is notoriously difficult to treat, and the prognosis was likely very poor, particularly in critically ill patients with cerebral involvement (2). After lung involvement, CNS is the second most common site, which leads to death in more than 90% of the cases (3). Patients with cranial Aspergillus typically present with fever unresponsive to antimicrobial therapy and usually include headache, meningeal irritation, vomiting, and cranial-nerve-related symptoms, seizures, mental alteration, or lethargy, but symptoms are variable and may also occur in other non-fungal CNS infections (4). Routine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis shows non-specific findings and histopathology and fungal culture have less sensitivity for diagnosis but are still suggested where tissue can be obtained, till molecular tests become available (5). However, testing for Aspergillus DNA or galactomannan test with validated polymerase chain reaction in cerebrospinal fluid specimens are promising techniques that can diagnose cranial Aspergillus (6). A combination of antifungal therapy and neurosurgical management, which hopefully promote further improvement of the still unsatisfactory prognosis of patients with cerebral aspergillosis, should be done for the patients (7). We report a case with cerebral aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient without the involvement of the lungs or sinuses. There are some interesting aspects of our case. First, cerebral aspergillosis has been reported in only about 10% of all cases of aspergillosis (8). In addition, invasive aspergillosis is most likely to infect the sinuses and lungs (9), and secondarily CNS is invaded by hematogenous spread from primary sites of infection (10). Third, invasive aspergillosis in an immunocompetent host is very rare (11).

2. Case Presentation

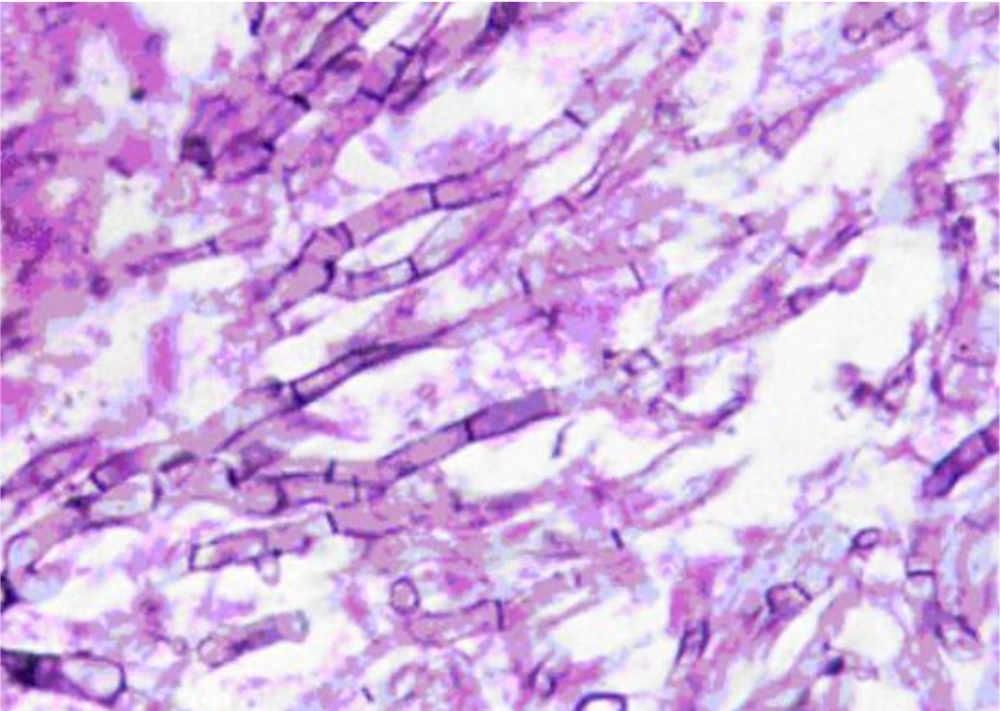

A 35-year-old man, presenting with progressive left hemifacial paresthesia followed by severe pain in trigeminal nerve territory, was admitted. He was a university professor who had been working in a research animal mycology lab, and there was no history of pre-existing comorbidities, and he was not on any medication. He did not have any risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection such as a history of promiscuous behavior or intravenous drug abuse, HIV test was negative. Total cell blood count (CBC) and routine serum factors in peripheral blood, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), fasting blood sugar, and A1C hemoglobin were in the normal range. Clinical examination revealed no sign of infection in the middle auditory canals, oral cavity, or nasal cavity. The initial neurologic examination did not reveal any sensory and motor deficit except for fifth nerve palsy and difficult mastication, examination of other systems was unremarkable. The patient underwent radiologic evaluations that the computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain showed an ill-defined low-density lesion at the right internal capsule and basal ganglia with mass effect to adjacent structures and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with and without gadolinium revealed T1 iso and T2 low signal lesion in the left parasellar region with enhancement. The lesion was extended to the left side of the prepontine cistern in the course of the trigeminal nerve. Also, an enhancement was seen on the left side of the sphenoidal body and sinus. The appearance suggested trigeminal schwannoma with extension from pons to Meckel’scave (Figure 1). Craniotomy and total surgical resection of the mass was performed. Evaluation of the Aspergillus fungal elements in H&E slides from brain tissue in the microscopic evaluation and histopathologic analysis showed fungal elements with acute branching septate hyphae, which was compatible with Aspergillus (Figure 2).

Axial sections of brain MRI demonstrate lesion in the left parasellar area isointense with brain parenchyma in T1-weighted (A) and low signal in T2-weighted (B) sequences. After contrast (C), avid enhancement is present, and a further extension to the left prepontine cistern (arrow) is better depicted.

The patient was operated, and the lesion was resected, on the basis of the histopathological findings, the patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B deoxycholate (1 mg per kg intravenously daily), but there was no improvement in clinical outcome when the patient was switched over to intravenous voriconazole at a dosage of 6 mg/kg twice daily on day one followed by 4 mg/kg/day, then after seven days, he was taken oral voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which improved patient’s status and reduced the volume of the brain aspergilloma after maintaining the treatment for six months. Workup for probable extracranial source, including thorough physical examination, chest and paranasal sinus CT scan, two-dimensional echocardiogram, and specific fungal blood cultures, as well as sinonasal endoscopy, were normal, and voriconazole was discontinued since the lesion totally disappeared on MRI without any complications.

After three years of treatment, he experienced new progressive headache, nausea and vomiting, visual disturbance, and somnolence. Repeated brain MRI revealed communicating hydrocephalus. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy was done, and the third ventricle was re-evaluated. He underwent ETV, and based on positive findings of fungal meningitis, surgical resection of Aspergillus-infected tissue was done, and voriconazole was restarted (6 mg per kg intravenously twice a day on day 1, followed by 4 mg per kg intravenously twice daily).

Unfortunately, several surgeries were needed to replace the malfunctioning of EVD. His clinical presentations revealed suspected acute central nervous system infections, bacterial meningitis, as the most common post shunt surgery complications, and treatment with antifungal and antibacterial agents were ineffective. Finally, the patient died on the twentieth day of the second admission.

3. Discussion

In immunocompetent patients, cerebral aspergillosis is rare and poorly described, but the mortality risk usually exceeds 90% in immunocompromised patients (12). A major reason for poor prognosis of survival in CNS aspergillosis is a suboptimal penetration of antifungal medications into the CNS, except for voriconazole as a preferred treatment option. Antifungal therapy with voriconazole results in therapeutic drug levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, which may exceed the minimal inhibitory concentration for Aspergillus (10). The most common sites of primary Aspergillus infection are lungs or maxillary sinusitis of dental origin (13, 14). Aspergilloma spreads by hematogenous dissemination into the CNS, paranasal sinuses, and respiratory tract, also infections reach the brain directly from the nasal sinuses via vascular channels or spread through contamination by blood from the lungs and gastrointestinal tract (15). The clinical presentation of cerebral aspergilloma typically includes a headache, depressed level of consciousness, seizures, stroke-like illness, palsy of the sixth nerve, and raised intracranial pressure, brain abscess, meningitis, and granulomatous mass (16). In our case, brain aspergillosis is presented with a tumor-like granulomatous mass with dural enhancement in favor of aspergilloma. These masses are hypo- to isointense on T1 and hypo-intense on T2W images with contrast enhancement. In this regard, in a large case series, including 40 cases of intracranial fungal granuloma during more than two decades, Aspergillus was the most frequent cause. Most patients had a predisposing factor, which was higher than previously reported studies, primarily diabetes mellitus, and tuberculosis (17). Our case is an example of the rare presentation of fungal infection. Hence, we conclude that the diagnosis of Aspergillus of the CNS is difficult and is frequently missed. Proper clinical, Ct scan or MRI of the head with or without intravenous contrast and hematological evaluation with direct histopathological examination and culture are the ultimate requirements for the final diagnosis of the cerebral aspergilloma. In these persons, a high index of suspicion, aggressive approach of diagnosis with timely and vigorous neurosurgical treatment, and antifungal treatment are indicated for proper eradication of the infection. This patient suggests that cerebral aspergillosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of CNS lesions. Therefore, rapid diagnosis and the combination of neurosurgical resection and antifungal therapy are required to have favorable outcomes. This case is unique because it shows primary cerebral aspergillosis in a person with an unknown immune disease. Indeed, he was a researcher in a mycology lab, and massive exposure to Aspergillus spores might be the probable reason.