1. Background

Candida species mainly Candida albicans are the causative agents of up to 20% - 25% of urinary tract infection (UTI) in intensive care units (ICUs), and the most common organisms after Escherichia coli (E. coli) (1). They can cause a range of infections from non-life threatening mucocutaneous diseases to life-threatening invasive and disseminated infections (2, 3). The entrance of Candida spp. to the urine (candiduria), is typically symptomless and has no features to indicate UTI (4). Candiduria is more common in hospitalized patients with indwelling devices and especially those in ICUs. Fungal UTIs are clearly rare in comparison with bacterial UTIs, however there has been an increase in the prevalence of Candida spp. causing UTIs since 1980s (5). Candida species present in the urinary tract via the climbing route, from the urethra to the bladder, and hematogenous dissemination by filtration of Candida spp. in kidneys and excretion to the urine (6). Urinary tract instrumentation, prolonged hospitalized stay, widespread antibiotic consumption, extremes of age, corticosteroid therapy, organ transplantation, female gender, diabetes mellitus, and use of immunosuppressive agents are the most predisposing factors (7). Candida albicans is the most prevalent etiologic agent for UTI however non-albicans Candida species (NACs) such as C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis are also isolated from UTIs (8-10).

2. Objectives

The aim of the present study was to identify the etiologic agents of Candida UTI among hospitalized patients at the ICU ward of Al-Zahra university hospital in Isfahan, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients with pyuria, and those patients who had antibacterial-resistant fever. The presence of blood and protein on urinalysis was a supporting sign of a Candida UTI only if yeasts alone were grown; without bacterial growth (4). In patients with indwelling catheters, colony counts ranged between 2 × 104 and ≥ 105 colony-forming units (CFUs)/mL; and for those patients without indwelling catheters colony counts as low as 104 CFU/mL. For those patients who had an indwelling catheter, replacement of catheter with a new device was performed and then the second urine sample was collected. If there was growth in the next sample, we considered UTI for the patient (4, 10, 11).

3.2. Isolates

From March 2017 to October 2018, 5281 patients were hospitalized at the ICU ward of Al-Zahra university hospital in Isfahan, Iran. One hundred patients out of 5281 (1.9%) were diagnosed as Candida UTI. The clinical isolates were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Biolife, Italy), and incubated at 37°C for 48 hours.

3.3. Phenotypic Identification

The sediments of urine specimens were initially sub-cultured on chromogenic medium (CHROMagar, DIFCO; Becton Dickinson, France) and incubated at 30°C for 24 - 48 hours. Species identification was performed based on chromogenic reaction of Candida species. Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, and other species produce green, metallic blue, pink, and white to mauve colonies, respectively.

3.4. Molecular Identification

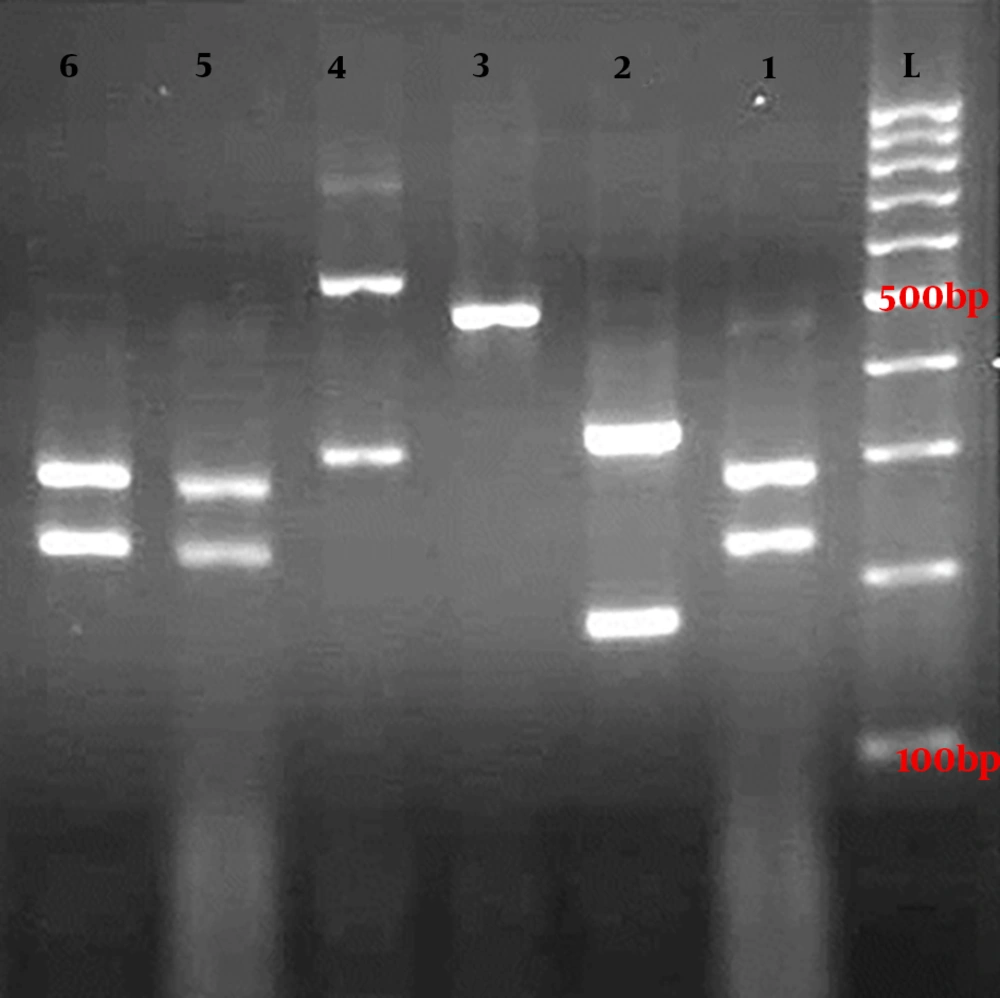

Genomic DNA of clinical isolates were extracted using the boiling method (12). Briefly, a loopful of fresh colonies were suspended in 150 µL of double distilled water (DDW) and boiled for 20 minutes, then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 8000 rpm, finally the supernatant was used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The ITS1-5.8SrDNA-ITS2 region was amplified by a PCR mixture containing of 5 µL of 10× reaction buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM dNTPs, 30 pmol of both ITS1 (5’-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G-3’) and ITS4 (5’-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3’) primers, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase, and 3 µL of DNA in a final volume of 50 µL. The PCR cycling condition was: an initial denaturation phase at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 45 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension phase at 72°C for 7 minutes. In the second step, the HpaII restriction enzyme (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) was applied to digest amplified products. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) products were separated by gel electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel (containing 0.5 µg/mL ethidium bromide) and photographed by Uvidoc (Cleaver Scientific Ltd, UK).

4. Results

Candida albicans was the most prevalent species among clinical isolates (94%) followed by Candida tropicalis (4%), Candida glabrata (1%), and Candida parapsilosis (1%) (Figure 1). Median age of patients was 61.8 (SD = 18.5). Male to female sex ratio was 40/60. The age range of (71 - 80) (24%) and (1 - 10) (1%) had the most and the least frequencies. All patients had urinary catheters. Forty four and 11 patients were diabetic and neutropenic, respectively. Two patients had undergone kidney transplantation. Hospitalization period was 2 - 40 days. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients in the present study.

| No. | Gender | Age | Neutropenia | Diabetes Mellitus | Kidney Transplantation | Immunosuppressive Therapy | Antimicrobial Usage | Duration of Hospitalization (Day) | Candida spp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 73 | + | + | - | Azathioprine | + | 14 | C. albicans |

| 2 | Male | 42 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | C. albicans |

| 3 | Male | 72 | + | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 5 | C. albicans |

| 4 | Male | 37 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | C. albicans |

| 5 | Female | 73 | - | + | - | - | + | 6 | C. tropicalis |

| 6 | Male | 63 | - | + | - | - | - | 3 | C. albicans |

| 7 | Female | 32 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | C. albicans |

| 8 | Female | 48 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | C. albicans |

| 9 | Male | 75 | - | + | - | - | + | 13 | C. albicans |

| 10 | Male | 76 | - | + | - | - | + | 29 | C. albicans |

| 11 | Female | 42 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | C. albicans |

| 12 | Female | 86 | - | + | - | - | + | 5 | C. albicans |

| 13 | Female | 22 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | C. albicans |

| 14 | Male | 81 | - | - | - | - | + | 18 | C. albicans |

| 15 | Male | 73 | - | + | - | - | - | 2 | C. albicans |

| 16 | Female | 34 | - | - | + | Tacrolimus | + | 6 | C. albicans |

| 17 | Male | 36 | - | - | - | - | - | 39 | C. albicans |

| 18 | Female | 84 | + | + | - | Azathioprine | + | 6 | C. albicans |

| 19 | Male | 83 | - | + | - | - | - | 5 | C. albicans |

| 20 | Female | 70 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | C. albicans |

| 21 | Male | 59 | - | - | + | Tacrolimus | + | 2 | C. albicans |

| 22 | Female | 51 | - | + | - | - | - | 6 | C. albicans |

| 23 | Male | 62 | - | + | - | - | - | 5 | C. albicans |

| 24 | Male | 36 | - | - | - | - | + | 9 | C. albicans |

| 25 | Female | 41 | - | - | - | - | + | 2 | C. albicans |

| 26 | Female | 60 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | C. albicans |

| 27 | Female | 24 | - | - | - | - | + | 8 | C. albicans |

| 28 | Male | 73 | - | - | - | - | - | 9 | C. albicans |

| 29 | Female | 71 | - | - | - | - | + | 5 | C. albicans |

| 30 | Male | 65 | - | + | - | - | + | 15 | C. albicans |

| 31 | Female | 62 | + | + | - | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | - | 15 | C. albicans |

| 32 | Female | 77 | - | - | - | - | + | 6 | C. albicans |

| 33 | Female | 71 | - | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 5 | C. albicans |

| 34 | Female | 27 | - | - | - | Corticosteroid | - | 6 | C. albicans |

| 35 | Female | 65 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | C. tropicalis |

| 36 | Female | 55 | - | + | - | - | + | 2 | C. albicans |

| 37 | Female | 87 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | C. albicans |

| 38 | Male | 61 | - | - | - | - | + | 4 | C. albicans |

| 39 | Female | 78 | - | - | - | - | + | 21 | C. albicans |

| 40 | Female | 88 | - | + | - | - | + | 4 | C. albicans |

| 41 | Female | 75 | - | - | - | - | + | 21 | C. albicans |

| 42 | Female | 82 | - | - | - | - | - | 23 | C. albicans |

| 43 | Female | 75 | - | + | - | - | + | 2 | C. albicans |

| 44 | Male | 79 | + | + | - | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | - | 3 | C. albicans |

| 45 | Male | 49 | - | - | - | - | - | 9 | C. albicans |

| 46 | Female | 80 | + | + | - | Corticosteroid | - | 21 | C. albicans |

| 47 | Female | 88 | - | - | - | - | + | 11 | C. albicans |

| 48 | Female | 76 | - | + | - | - | + | 24 | C. albicans |

| 49 | Female | 65 | - | + | - | - | + | 7 | C. albicans |

| 50 | Female | 74 | - | + | - | Corticosteroid | - | 9 | C. albicans |

| 51 | Male | 80 | - | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 6 | C. albicans |

| 52 | Female | 61 | - | - | - | - | + | 12 | C. albicans |

| 53 | Male | 84 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | C. albicans |

| 54 | Female | 90 | - | - | - | - | - | 30 | C. albicans |

| 55 | Female | 50 | + | - | - | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | - | 3 | C. tropicalis |

| 56 | Male | 59 | - | + | - | - | - | 9 | C. albicans |

| 57 | Female | 73 | - | - | - | - | + | 10 | C. albicans |

| 58 | Male | 47 | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | C. albicans |

| 59 | Male | 39 | - | - | - | - | + | 40 | C. albicans |

| 60 | Male | 63 | + | - | - | Corticosteroid | + | 35 | C. parapsilosis |

| 61 | Male | 77 | - | + | - | - | - | 15 | C. albicans |

| 62 | Female | 68 | - | + | - | - | + | 40 | C. albicans |

| 63 | Female | 57 | - | + | - | - | - | 32 | C. albicans |

| 64 | Male | 72 | - | - | - | - | + | 25 | C. glabrata |

| 65 | Male | 39 | - | - | - | - | + | 26 | C. albicans |

| 66 | Female | 56 | + | - | - | Corticosteroid | - | 10 | C. albicans |

| 67 | Male | 84 | - | - | - | - | + | 5 | C. albicans |

| 68 | Male | 69 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | C. albicans |

| 69 | Female | 95 | - | - | - | - | + | 5 | C. albicans |

| 70 | Female | 55 | - | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 25 | C. albicans |

| 71 | Male | 59 | - | - | - | Corticosteroid | + | 30 | C. albicans |

| 72 | Female | 73 | - | + | - | - | - | 6 | C. albicans |

| 73 | Male | 47 | - | - | - | - | + | 29 | C. albicans |

| 74 | Female | 55 | + | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 23 | C. albicans |

| 75 | Female | 87 | - | + | - | - | - | 20 | C. albicans |

| 76 | Male | 61 | - | - | - | - | + | 10 | C. albicans |

| 77 | Female | 30 | - | - | - | Corticosteroid | + | 20 | C. tropicalis |

| 78 | Female | 74 | - | + | - | - | - | 16 | C. albicans |

| 79 | Female | 7 | - | - | - | - | + | 10 | C. albicans |

| 80 | Male | 43 | - | + | - | - | + | 27 | C. albicans |

| 81 | Female | 24 | - | - | - | - | + | 32 | C. albicans |

| 82 | Male | 70 | - | + | - | - | - | 15 | C. albicans |

| 83 | Female | 65 | - | + | - | - | - | 7 | C. albicans |

| 84 | Female | 69 | - | + | - | - | + | 10 | C. albicans |

| 85 | Male | 43 | + | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 27 | C. albicans |

| 86 | Female | 38 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | C. albicans |

| 87 | Female | 52 | - | + | - | - | - | 14 | C. albicans |

| 88 | Female | 54 | - | - | - | - | + | 18 | C. albicans |

| 89 | Female | 30 | - | - | - | - | + | 20 | C. albicans |

| 90 | Male | 59 | - | + | - | - | + | 20 | C. albicans |

| 91 | Female | 40 | - | + | - | - | - | 10 | C. albicans |

| 92 | Female | 64 | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | C. albicans |

| 93 | Male | 74 | - | - | - | Corticosteroid | + | 9 | C. albicans |

| 94 | Female | 68 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | C. albicans |

| 95 | Female | 83 | - | + | - | - | + | 25 | C. albicans |

| 96 | Female | 58 | - | - | - | Corticosteroid | - | 15 | C. albicans |

| 97 | Female | 81 | - | + | - | Corticosteroid | + | 19 | C. albicans |

| 98 | Female | 32 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | C. albicans |

| 99 | Male | 63 | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | C. albicans |

| 100 | Male | 69 | - | + | - | - | + | 7 | C. albicans |

Gel electrophoresis of ITS-PCR amplicons of Candida species after digestion with MspI restriction enzyme. Lanes 1, 5, and 6 are C. albicans (238 and 297 bp), lane 2 is C. tropicalis (184 and 340 bp), lane 3 is C. parapsilosis (520 bp), lane 4 is C. glabrata (314 and 557 bp), and lane L is a 100-bp DNA size marker.

5. Discussion

UTI is regularly found in patients with immunosuppressive conditions, long hospitalization, and who have undergone surgical procedures. Alvarez-Lerma from Spain showed that 10% - 15% urinary tract infections in the ICU patients are caused by the Candida species and 22% of critically ill patients hospitalized for more than seven days in ICUs revealed candiduria (13). During 1995 - 2001, there was 25,000 cases of candiduria per year in the United States (14). Diabetes mellitus is a formidable risk factor for the infection, since the mucous membranes in this group are more susceptible to UTI due to immune deficiencies (15). Candida colonization was elevated in the present of nitrogenous compounds and acidic pH. In the present study, 44% of patients were diabetic as a major predisposing factor for UTI. The majority of UTI cases are catheter users (16). In accordance, all patients in the present investigation used urethral catheters. In agreement with our findings, Candida albicans is the most prevalent Candida species causing candiduria (17, 18), however there is a substantial trend to non-albicans Candida species (19, 20). A high number of cases of UTI due to the non-albicans species may be in connection with fluconazole consumption as a first line antifungal therapy because many Candida species are inherently resistant to flocuazole or susceptible only to high doses of this antifungal drug such as Candida krusei and Candida glabrata (1). The limitation of our study was the lack of determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the clinical isolates which is strongly recommended for further studies. Some studies introduce Cryptococcus neoformans and Trichosporon asahii as etiologic agents of UTI (21) but, Candida was the only fungus isolated from patients enrolled in the present investigation. A recurrent Candida UTI is a rare clinical manifestation and appears in diabetic patients or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract (22). Diabetes mellitus is a main risk factor for development of candidemia and is reported in nearly one third of all UTI patients (23). We followed up all patients especially diabetic patients (44%) and fortunately nobody presented systemic candidiasis in the present investigation. Similar to the present study, females usually have a higher chance for candiduria and UTI (24) in connection with vulvovaginal colonization by Candida species and their anatomy (6, 25), however, in many investigations males are the predominant population among UTI patients (11, 26). Candida species are isolated from 20-60% of UTI in neonatal intensive care units (NICU) and pediatric intensive care units (PICU) (27), but in the present study, the frequency of UTI among infants was only 1%. Since older individuals reveal natural modifications of the immune system, so longer hospitalization in intensive care units and use of urinary catheters was seen more commonly in this population (28, 29). Similar to most surveys in this field (6, 27), most patients in the present investigation were over 65 years old. The median absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 1.5 × 109/L is considered as neutropenia (30, 31). In the present study 11% of patients were neutropenic with the mid age of 65.2 years.

5.1. Conclusions

Patients with candiduria and UTI in ICU have increased mortality rates (13), so good management of patients depends on quick and precise intercessions. Since Candida albicans was a predominant species in the present study (94%), and it shows different sensitivities to antifungal drugs, determination of MIC for clinical isolates are recommended to determine the best choice for this potentially dangerous infection.