1. Background

Strongyloides stercoralis, a soil transmitted helminth, is well known as a potentially fatal parasite. Strongyloides stercoralis is able to develop chronic infection as larvae can re-infect the host via internal and external auto-infection. This parasite may also cause hyper infection in some patients through the auto-infection (1). However, S. stercoralis may be asymptomatic for several years and is therefore considered as a neglected parasitic infection. Furthermore, the lack of a gold standard for the diagnosis of infection, and the relative absence of effective treatment has delayed both the research and treatment of this chronic infection (2). Strongyloidiasis is a cosmopolitan parasite infection, but is more prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions particularly in populations with poor sanitation (2). Several factors increase the risk of S. stercoralis infection in humans such as low socioeconomic status, gender, occupation, malnutrition, and immunosuppressive disorders such as HIV, hypogammaglobulinemia and diabetes mellitus (3).

A positive association between S. stercoralis infection and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been reported in Brazil (4) but a study performed in India suggested a negative relationship between these conditions (5). A study conducted by Hays et al., provides some evidence that chronic infection with S. stercoralis may protect against the development of T2DM in humans (6). Subsequently, they reported that glycemic control occurs in patients with pre-existing T2DM who were treated with ivermectin compared with non-treated cases (7). However, the complex nature of the interactions between Strongyloides sp. infections and T2DM is not clearly understood and may be a result from the process of immunomodulation in such patients (6).

Very little research attention has been given to the prevalence of S. stercoralis among T2DM patients. Several case report studies have demonstrated that this infection can be severe in such patients (8, 9). There are few reports of S. stercoralis infection in T2DM patients from Iran (10, 11). Recently, Sharifdini et al., reported a hyperinfection in an unconscious diabetic patient with dermatomyositis from Mazandaran province, northern Iran (12). This province has a humid, temperate climate, and is known to be endemic for S. stercoralis with several documented cases of hyperinfection (12, 13).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of strongyloidiasis in diabetic patients, in the central parts of Mazandaran province, Iran, using coprological examination and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

3. Methods

3.1. Ethical Considerations and Population Study

This cross-sectional study was conducted on diabetic patients who were referred to the outpatient clinic at Ayatollah Rouhani Hospital, Babol, Iran, during January 2018 to August 2018. The purpose of this study was explained to each participant and they gave their informed agreement. This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of Babol University of Medical Science, Babol, Iran (Code: MUBABOL.HRI.REC.1396.136). All participants were under the supervision of a specialist in internal medicine. Demographic information and clinical data were collected using a questionnaire form.

3.2. Sample Collection

Two mL of blood was obtained from each diabetic patient and the serum was collected after centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes. The serum was kept at -20°C until use. A clean stool sample container was given to each subject to collect fresh fecal specimens.

3.3. Laboratory Techniques

Stool samples were examined using direct smear and formol-ether concentration. The serum samples were tested for the existence of Strongyloides sp. antibodies using Strongyloides - ELISA diagnostic kit (Novalisa, NovaTec, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm by an automatic ELISA reader and the results were read and interpreted according to the kit’s guideline.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

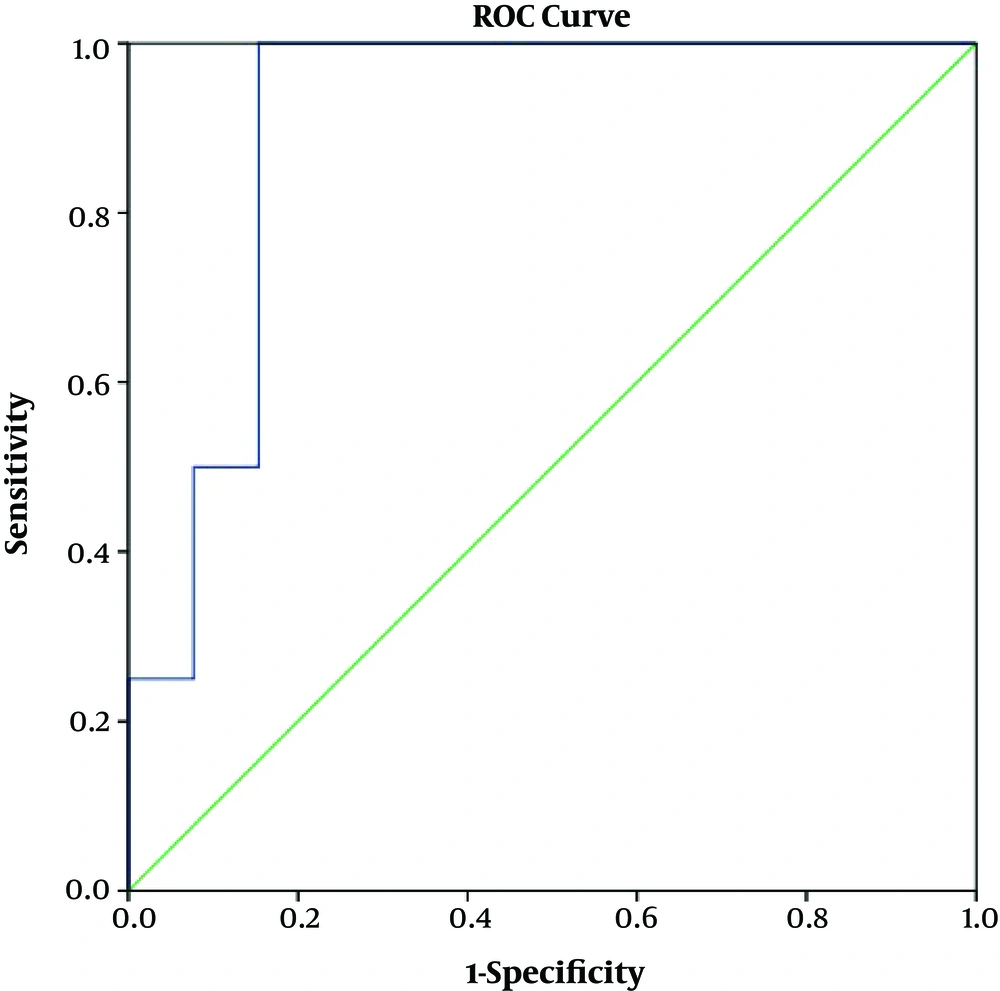

To analyze the data chi-square and t-test were used to determine association between different factors and seropositive results using SPSS software version 22. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A statistically significant difference was considered at P < 0.05. The optimum point for ELISA reactions and cut-off points were obtained by receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC).

4. Results

A total of 180 diabetic patients participated in the present study. There were 8 missing pieces of data for some variables including residence, occupation and experience of rice field work. The mean age of the patients was 55.8 ± 9.5 ranging from 33 to 80 years. Out of 180 patients, 139 were female (77.2%) and 41 cases were male (22.8%). Eighty-five (47.2%) and 87 (48.3%) subjects lived in urban and rural areas, respectively. Corticosteroids were not used by any patients. Out of 173 patients, 79 cases had other diseases such as heart diseases and kidney failure in addition to diabetes (Tables 1 and 2).

Of 180 patients, 30 participants provided stool specimens, which were tested with parasitological techniques to assess the presence of S. stercoralis larvae and other possible parasite infections. Stool examination showed that the prevalence rate of S. stercoralis infection was 13.3% (4/30). All cases had experience of agriculture and gardening, and three of them (75%) lived in rural areas. One out of 4 subjects had gastrointestinal disorders.

Out of 180 diabetic patients, 46, 7, and 127 cases were seropositive, borderline and seronegative, respectively using the ELISA assay. Borderline titer was considered negative to perform single variable analysis. The overall seropositivity rate was 25.6% (46/180). The rate of this infection was higher in females (27.3%) than males (19.5%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (OR = 0.64, CI 95%: 0.273 - 1.519, P = 0.32). The prevalence rate of Strongyloides sp. infection was higher in participants living in rural regions (31%) compared with urban areas (20%) [OR = 1.8, CI 95%: 0.895 - 3.622, P = 0.1]. In comparison with other occupations, homemakers had the highest prevalence rate for this infection (30.9%) followed by farmers (23.8%). The distribution of Strongyloides sp. infection among participants based on sociodemographic data is shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Total, No. (%) | Positive, No. (%) | Negative, No. (%) | P Value | Odd Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| < 50 | 52 (28.9) | 10 (19.2) | 42 (80.8) | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.350 - 2.151 |

| 50 - 60 | 63 (35) | 22 (34.9) | 41 (65.1) | 0.10 | 1.96 | 0.891 - 4.290 |

| > 60 | 65 (36.1) | 14 (21.5) | 51 (78.5) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 41 (22.8) | 8 (19.5) | 33 (80.5) | 0.32 | 0.64 | 0.273 - 1.519 |

| Female | 139 (77.2) | 38 (27.3) | 101 (72.7) | |||

| Total | 180 (100) | |||||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 85 ( 49.4) | 17 (20) | 68 (80.3) | 0.10 | 1.80 | 0.895 - 3.622 |

| Rural | 87 (50.6) | 27 (31.0) | 60 (69.0) | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Homemaker | 84 (48.8) | 26 (30.9) | 58 (69.01) | 0.20 | 1.86 | 0.721 - 4.784 |

| Farmer | 21 (12.2) | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | 0.70 | 1.30 | 0.353 - 4.750 |

| Administrative work | 31 (18.0) | 6 (19.4) | 25 (80.6) | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.295 - 3.350 |

| Other jobs | 36 (21.0) | 7 (19.4) | 29 (80.6) | |||

| Farm experiences | ||||||

| Yes | 89 (51.7) | 23 (25.8) | 66 (74.2) | 0.94 | 1.10 | 0.518 - 2.042 |

| No | 83 (48.3) | 21 (25.3) | 62 (74.7) | |||

| Walk barefoot | ||||||

| Yes | 84 (48.8) | 20 (23.8) | 63 (76.2) | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.537 - 2.112 |

| No | 88 (51.2) | 22 (25.0) | 66 (75) | |||

| Rice farmer | ||||||

| Yes | 43 (25) | 11 (25.6) | 32 (64.4) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.453 - 2.206 |

| No | 129 (75) | 33 (25.6) | 96 (74.4) | |||

| Total | 172 (100) |

The distribution of Strongyloides sp. infection among diabetic patients based on clinical features and blood groups is shown in Table 2. The prevalence rate of Strongyloides sp. infection was higher in patients with diabetic foot (39.1%) compared with non-diabetic foot cases (23.6%) [OR = 2.1, CI 95%: 0.835 - 5.402, P = 0.15]. Strongyloides sp. infection was more prevalent in patients with the O blood type (34.3%). It also was more prevalent in patients with other systemic diseases such as gastrointestinal disorders, heart and kidney syndromes in addition to diabetes. Gastrointestinal disorders were observed in 9 patients but only 2 (22.2%) were seropositive. The prevalence rate of Strongyloides sp. infection was higher among insulin dependent patients (29.9%) compared with non-insulin dependent subjects (23%) (P = 0.31).

The median values and interquartile ranges (IQRs) of antibody titer against Strongyloides sp. were 42.0 (16.3 - 46.0) and 5.4 (3.6 - 7.0) for seropositive and seronegative diabetic patients, respectively (Table 3).

| Variables | Total | Seropositive | Seronegative | P Value | Odd Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of medication | ||||||

| Insulin | 67 (37.2) | 20 (29.9) | 47 (70.1) | 0.31 | 0.70 | 0.355 - 1.390 |

| Non-insulin | 113 (62.8) | 26 (23.0) | 87 (77.0) | |||

| Other disease | ||||||

| Yes | 76 (42.2) | 22 (28.9) | 54 (71.1) | 0.37 | 1.36 | 0.692 - 2.664 |

| No | 104 (57.8) | 24(23.1) | 80 (76.9) | |||

| Family history | ||||||

| Yes | 133 (73.9) | 33 (24.8) | 100 (75.2) | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.407 - 1.828 |

| No | 47 (26.1) | 13 (27.7) | 34 (72.3) | |||

| Diabetic foot | ||||||

| Yes | 23 (12.8) | 9 (39.1) | 14 (60.9) | 0.15 | 2.1 | 0.835 - 5.25 |

| No | 157 (87.2) | 37 (23.6) | 120 (76.4) | |||

| Blood Groups | ||||||

| O | 67 (37.8) | 24 (35.8) | 43 (64.2) | 0.73 | 1.26 | 0.349 - 4.514 |

| A | 51 (28.8) | 8 (15.7) | 43 (84.3) | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.103 - 1.696 |

| B | 46 (54.1) | 10 (21.7) | 36 (78.3) | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.159 - 2.461 |

| AB | 13 (7.3) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | |||

| RH | ||||||

| Positive | 163 (92.1) | 44 (27.0) | 119 (73) | 0.31 | 2.22 | 0.477 - 10.311 |

| Negative | 14 (7.9) | 2 (14.3) | 12 (85.7) |

| Variables | Total | Seropositive | Seronegative | P Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD | 55.8 ± 9.5 | 56.2 ± 8.7 | 55.7 ± 9.8 | 0.75 | -3.717 - 2.697 |

| Median & IQRs of age | 55.5 (50.0 - 62.0) | 54.5 (51.0 - 62.3) | 56.0 (49.0 - 62.0) | 53.60 - 58.74, 54.0 - 57.3 | |

| Mean age of diabetic ± SD | 45.3 ± 10.3 | 46.2 ± 8.5 | 44.9 ± 10.9 | 0.45 | -4.813 - 2.154 |

| Median & IQRs of diabetic age | 44.0 (38.0 - 52.0) | 46.0 (40.0 - 51.5) | 44.0 (37.0 - 52.5) | 43.71 - 48.78, 43.05 - 44.78 | |

| Mean of creatinine | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.38 | 1.2 ± 0.36 | 0.37 | -0.068 - 0.184 |

| Median & IQRs of creatinine | 1.1 (0.9 - 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8 - 1.4) | 1.1 (1.0 - 1.3) | 1.13 - 1.24, 1.12 - 1.25 | |

| Mean of Ig titer | 12.9 ± 15.0 | 34.6 ± 15.4 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 0.00 | -31.7605 - -26.3824 |

| Median & IQRs of Ig titer | 6.3 (4.2 - 11.4) | 42.0 (16.3 - 46.0) | 5.4 (3.6 - 7.0) | 30.07 - 39.13, 5.11 - 5.86 |

The sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of ELISA, compared with the primary reference standard test (larvae detection), were 100%, 84.6%, 50% and 100%, respectively. The ROC curve of ELISA compared with stool examination is presented in Figure 1. The optimum cut-off point was 10.45, in which the SE and SP are approximately equal (100% and 85%, respectively). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.904 (95% CI: 0.790 - 1.00).

5. Discussion

The present study found that the prevalence of S. stercoralis infection in diabetic patients was 13.3% (4/30) and 25.5% (46/180) by stool examination and ELISA, respectively. Previously documented studies report that the seroprevalence of S. stercoralis is 24.5% and 23% in diabetic Australian aboriginal patients and Brazil, respectively, which is similar to results obtained from our study (4, 6). However, our findings are not supported by studies conducted in different populations, without diabetic patients from Iran. By stool examination, the prevalence of this infection has been reported from 1.4% to 4.9% in Mazandaran which is lower than the results obtained by the present work (13.3%) (13, 14). Moreover, the seroprevalence rate of this infection was higher than a study performed by Rafiei et al. (15), in Southwest Iran (14.4%) and other studies conducted in different parts of the world such as do Rio de Janeiro (13%) (16) and in Bangladesh (22%) (17). Lower prevalence rates were observed in our study compared to other investigations performed in Thailand (34.2%) (18), Bangladesh (61.2%) (19) and the Peruvian Amazon (72%) (20).

This work found that the seroprevalence of this infection was not significantly higher in cases living in rural areas compared with those living in urban settings. Also, no significant difference was observed between S. stercoralis infection and age groups, gender and other demographic data, which agrees with some previous studies (15, 17). It was also observed that homemaker and farmers are at risk of strongyloidiasis more than other occupations (Table 1) which is in agreement with published data (20, 21). These results may occur because of the nature of the parasite, soil transmitted helminths, and therefore people who have soil contact are more at risk for S. stercoralis infection (21). However, no significant differences were observed between S. stercoralis infection and the clinical features of the patients. The patients with diabetic foot were at risk of strongyloidiasis more than subjects without this disorder. A study conducted by Gill et al., found that tropical ulcer was more common among cases with Strongyloides sp. infection compared with non-infected subjects (22).

On the other hand, Strongyloides sp. infection was diagnosed in only one patient with gastrointestinal disorders by both stool examination and ELISA. Also, no symptoms and signs indicating hyperinfection were observed in any of the patients. All of the studied cases were under metabolic control of diabetes and did not undergo corticosteroid therapy or suffer severe metabolic distress. However, it is well known that strongyloidiasis manifests in most cases as a chronic asymptomatic disease and severe manifestations of this infection are frequently correlated with predisposing factors such as immunosuppression caused by other diseases or corticoid treatment (4). Corticosteroids therapy leads to hyper-infection or disseminated infection through the enhancement of apoptosis in T-lymphocytes, and also increasing steroid-like substances which act as modulating signals causing the rhabditiform larvae to change into infective filariform larvae (23).

The present study found that the prevalence of S. stercoralis infection in diabetic patients obtained by ELISA (25.5%) was almost two times higher than stool examination results (13.3%). The poor agreement which is observed between ELISA and coprological examination methods (P = 0.000, kappa = 0.11) is also reported by several studies throughout world (17, 24). Stool examination has low sensitivity and fails to detect S. stercoralis larvae in up to 70 % of cases particularly when single stool specimens are provided (25). On the other hand, serological tests usually overestimate results and cannot distinguish between past and current infections (26). The inconsistency between these methods may result from cross reactions between Strongyloides sp. and other helminthic infections including filariasis and schistosomiasis (27, 28). The aforementioned helminthic diseases were not reported from the studied area, but Ascaris lumbricoides and human hookworm infections are reported frequently, and therefore the possibility of cross reactions cannot be ruled out as the serum was not tested for other helminth infections. Furthermore, the disagreement between results obtained from ELISA and coprological analysis methods may be related to a high frequency of past infections in an endemic environment (29).

The limitations of this study, which may have impacted the results, were: first, the number of stool samples was not compatible with the number of serum samples; second, the sample size was small.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study demonstrated a high seroprevalence of Strongyloides sp. infection in diabetic patients. Furthermore, this is the first seroprevalence study of strongyloidiasis in diabetic patients from Iran. It was also observed that the ELISA technique has 100% sensitivity and 85% specificity compared with coprological examination. It seems that the ELISA technique can be used for the diagnosis of individual cases and is an efficient screening assay to rule out strongyloidiasis in diabetic patients.