1. Background

In 2017, an estimated 36.9 million people were living with HIV worldwide. Among them, 21.7 million were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 0.94 (0.67 - 1.3) million died from AIDS-related illnesses (1). The HIV pandemic is still a public health issue worldwide, especially in developing countries (2, 3). The disease is also growing in East Mediterranean region countries, including Iran (4, 5). According to the national HIV registry system, in 2017, the number of people living with HIV (PLWH) was 34,949 in Iran, including 84% men and 16% women, and the number of AIDS-related deaths was 9,477 by March 2017 (2, 6).

Since 2008, over eight million people received ART in developing countries (7). The ART regimens could significantly increase the quality and quantity of life of PLWH. An appropriate treatment, chosen at the right time, is crucial to achieving favorable outcomes. With effective treatment, there could be a substantial reduction in viral load and an increase in the number of CD4 cells; however, about 12% to 32% of patients fail to achieve these desirable outcomes (8, 9).

Besides the ART expansion, an emerging problem is HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) mutants, which are attributed to HIV mutating and replicating capabilities in the presence of ART drugs. The HIVDR deactivates the drugs which formerly could control viral replication. This has led to attempts in introducing more effective medications in ART regimens, which carry new side effects and consequently impose a more economic burden on both patients and health systems (7, 10).

Treatment failure and further spread of HIVDR mutants compromise the effectiveness of ART to meet “the last 90” target for viral suppression. It also increases HIV mortality and morbidity (7, 10, 11). Therefore, appropriate surveillance of HIV patients receiving ART should be implemented to improve adherence, which is essential to achieve the desired outcome and prevent the emergence of HIVDR mutants (7).

In Iran, ART is available and free of charge for all PLWH. Despite its beneficial therapeutic effects, recently, a growing body of evidence has shown that the first-line treatment fails sometimes; however, it is not clear which drug fails and how frequent it occurs (4, 10). Early detection of treatment failure could substantially reduce the complications and prevent new viral mutants to emerge.

2. Objectives

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of treatment failure and patterns of resistance to various ART drugs among PLWH in a major referral hospital in Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

We reviewed the medical charts of 1,700 HIV patients who referred to the voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) center of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran between 2004 and 2017. Patients who lost to care, died, transferred out, or incarcerated were excluded. We found a total of 72 patients with virologic failure (VF).

3.2. Instruments

The patient’s demographic characteristics, viral load markers, TCD4+ count, and selected ART regimen were extracted from the patients’ medical records using an information datasheet. The history of treatment failure, drug resistance results, and alternative regimens were also recorded. Treatment failure was determined based on the virologic features of patients. The 2018 AIDS info instruction (retrieved from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines) was applied to determine treatment failure. Based on this instruction, the presence of 200 or more copies per milliliter of viral load after six months of continuous, effective ART was considered a treatment failure. Resistance tests were performed for the viral loads of more than 1,000 copies/mL and based on the results, the second line regimen began. We included all drug resistance mutations that presented low-, intermediate-, or high-level resistance. The RNA genome of HIV has several genes such as reverse transcriptase (RT), protease (Pro), and integrase (INT). These genes may mutate and cause drug resistance in HIV-positive patients. For this reason, drug resistance was evaluated by the amplification of these genes using specific primers by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing of products. Then, the results of the analysis were extracted based on the Stanford HIV drug resistance website (hivdb.stanford.edu).

3.3. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). All the information sheets were secured in a locked shelve where only authorized persons had access to. The digital data file was secured by a password that was only known to study researchers.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the data, we used SPSS software (version 22). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study participants and frequency of different drug resistance patterns.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Study Population

We analyzed the data of 72 patients with VF. The majority of patients were male (68.1%), aged 35 - 50 years (61.1%), and unemployed (36.1%). Moreover, they mostly had high school education (51.4%), a history of drug use (55.6%), and acquired infection from high-risk heterosexual contacts (54.2%). Most of the patients were on an ART regimen for 37 months or longer (86.1%) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Valuesb |

|---|---|

| Male | 49 (68.1) |

| Age group, y | |

| 16 - 25 | 1 (1.4) |

| 26 - 34 | 17 (23.6) |

| 35 - 50 | 45 (61.1) |

| > 50 | 8 (11.1) |

| Unemployed | 26 (36.1) |

| Education level | |

| Illiterate | 3 (4.2) |

| Elementary school | 17 (23.6) |

| High school | 37 (51.4) |

| Academic | 9 (12.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 29 (40.3) |

| Married | 29 (40.3) |

| Divorced | 6 (8.3) |

| Widow | 3 (4.2) |

| Smoking status | |

| Ex-smoker | 11 (15.3) |

| Current smoker | 35 (48.6) |

| Past history of drug use | 40 (55.6) |

| Transmission route | |

| Heterosexual | 39 (54.2) |

| Homosexual | 3 (4.2) |

| Drug injection | 22 (30.6) |

| Others (mother to child, blood/blood product transfusion) | 4 (5.6) |

| ART duration, month | |

| 0 - 12 | 4 (5.6) |

| 13 - 24 | 3 (4.2) |

| 25 - 36 | 2 (2.8) |

| ≥ 37 | 62 (86.1) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bSubgroups do not always add up to total due to missing data.

4.2. Virologic Failure

The mean value of the first CD4 count (CD4 count right after ART initiation) was 262.4 cells/µL and the mean value of the last CD4 count (CD4 count after ART) was 349.6 cells/ µL. The mean value of the first viral load was 191,309.7 copies/mL while the mean value of the last viral load was 32,312.2 copies/mL. Following treatment, the mean value of the last CD4 count was significantly higher than the mean value of the first CD4 count (P < 0.001). In total, 72 out of 1700 (4.2%) HIV patients experienced treatment failure. The highest numbers of VF patients were receiving NNRTIs (n = 19; 26.4%) and NNRTIs + NRTIs (n = 32; 44.4%).

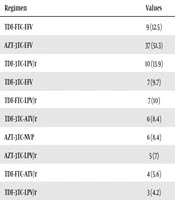

The most frequent failed regimens were AZT-3TC-EFV (51.3%), TDF-3TC-LPV/r (18.1%), and TDF-FTC-EFV (12.5%) (Table 2). The highest resistance levels were related to nevirapine (NVP) (73.6%) and efavirenz (EFV) (70.8%) (Table 3). There was no significant relationship between drug type and resistance level (P value > 0.05).

| Regimen | Values |

|---|---|

| TDF-FTC-EFV | 9 (12.5) |

| AZT-3TC-EFV | 37 (51.3) |

| TDF-3TC-LPV/r | 13 (18.1) |

| TDF-3TC-EFV | 7 (9.7) |

| TDF-FTC-LPV/r | 7 (10) |

| TDF-3TC-ATV/r | 6 (8.4) |

| AZT-3TC-NVP | 6 (8.4) |

| AZT-3TC-LPV/r | 5 (7) |

| TDF-FTC-ATV/r | 4 (5.6) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

| Medication | High-Level Resistance | Intermediate-Level Resistance | Low-Level Resistance | Total Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stavudine | 9 (50) | 4 (22.2) | 5 (27.8) | 18 (25) |

| Didanosine | 12 (44.4) | 6 (22.2) | 9 (33.3) | 27 (37.5) |

| Zidovudine | 12 (57.1) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (14.3) | 21 (29.2) |

| Abacavir | 12 (38.7) | 9 (29) | 10 (32.2) | 31 (43) |

| Lamivudine | 41 (93.2) | - | 3 (6.8) | 44 (61.1) |

| Emtricitabine | 35 (92) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) | 38 (52.8) |

| Tenofovir | 6 (28.6) | 5 (24) | 10 (48) | 21 (29.1) |

| Nevirapine | 47 (88.7) | 3 (5.7) | 3 (5.7) | 53 (73.6) |

| Efavirenz | 43 (84.3) | 5 (9.8) | 3 (5.9) | 51 (70.8) |

| Etravirine | 3 (9.4) | 12 (37.5) | 17 (53.1) | 32 (44.4) |

| Riplivirine | 10 (27) | 12 (32.4) | 15 (40.5) | 37 (51.3) |

| Lopinavir | 5 (83.3) | - | 1 (16.7) | 6 (8.3) |

| Atazanavir | 2 (33.3) | - | 4 (66.7) | 6 (8.3) |

| Darunavir | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | - | 2 (2.8) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

We found that HIV treatment failed in less than 5% of patients. The highest drug resistance belonged to NRTIs and NNRTIs combination. The highest rate of VF was attributed to nevirapine (NVP) and efavirenz (EFV). Resistance to tenofovir (TDF), as the most commonly prescribed NRTIs, was observed in less than one-third of patients.

Offering HIV mediations to all patients at the time of diagnosis or at early as possible after diagnosis worldwide raises concerns about emerging drug resistance, mainly due to the lack of compliance in regular and continuous drug intake. The patient’s adherence to therapy is a key component of a successful ART program (12, 13). Lack of knowledge in patients about ART and the importance of adherence, misconception about side effects, and dealing with many other priorities in life (14), feeling sick (15), and other co-infections and concomitant diseases (16) were reported as factors associated with ART nonadherence.

An increasing concern besides the ART extension is the emerging of HIVDR mutants, which is attributed to HIV mutating and replicating capabilities in the presence of ART drugs (8). In the current study, the highest resistance was observed to NRTIs + NNRTIs regimens (44%). In fact, the NNRTIs regimens sustained the most frequent drug resistance among which, NVP (74%) and EFV (71%) demonstrated the highest resistance rates. A similar study in Iran found resistance to NVP (21.3%) and EFV (19.7%) as the most frequent drug resistance rates among HIV patients (17). They also found that 36.1% of HIV patients had at least one mutation related to RT inhibitors. The RT inhibitor mutations were also reported to reduce the susceptibility to NRTIs and NNRTIs (17, 18). The G190A mutation is another common mutation that occurs in 36% of cases (19, 20) and it could reduce the viral response to NVP and EFV by more than 50 and 5 - 10 times, respectively (21, 22). There are also other mutations (23, 24) that can cause HIVDR.

Our study had three major limitations. First, we could not locate the data for all patients, particularly children, which limited the study external validity. Second, we used the medical record data and thus, the completeness and quality of data were not perfect and varied over time. Lastly, we assessed the drug resistance patterns only among patients with treatment failure.

Despite the limitations, our study characterized the ART resistance patterns among HIV patients for whom HIV treatment failed. Our findings propose to use protease inhibitors as first-line drugs in ART regimens in patients with VF.