1. Background

Pneumonia is a fairly prevalent illness and a common complication in critically ill patients, especially in patients who are intubated for more than 48 hours (1, 2). It is the main cause of hospital mortality (3). The most common findings on physical examination of the disease include tachypnea, tachycardia, fever with or without chills, and decreased bronchial breath sounds (4). Several factors, including age, hospital setting, and comorbidities are considered major factors affecting prognosis (4). Patients younger than four years and older than 60 years have a poorer prognosis than other age groups. Many causes of pneumonia are bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, but bacteria are the major cause of mortality and morbidity by pneumonia (4).

Types of bacterial pneumonia include Community-Acquired Pneumonia or CAP (acute infection of lung tissue, which has been acquired from the community), Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia or HAP (acute infection of lung tissue that develops 48 hours or more after hospitalization), healthcare-associated pneumonia or HCAP (acute infection of lung tissue acquired from health center or in patients hospitalized within the past 3 months), and VAP or ventilator-associated pneumonia (nosocomial infection of lung tissue that develops 48 hours or longer after intubation of mechanical ventilation). The most common complications of bacterial pneumonia are sepsis, multiorgan failure, respiratory failure, and coagulopathy (4).

Studies have shown that selective digestive tract decontamination decreases the occurrence of pneumonia; however, such decontamination is associated with increased rates of antimicrobial resistance (5, 6). Recently, some studies have proposed a promising effect of probiotics on preventing pneumonia in patients (7-10).

Probiotics are commercial microorganisms that may have health benefits to individuals when ingested (11-13). Prebiotics colonize the host’s gastrointestinal tract, change microbiota (10, 14-22), and exert antibacterial effects. They create an undesirable environment for pathogens via the following mechanisms, including the promotion of gut’s defense barrier (via normalization of permeability of intestine), modulation of secretory immunoglobulin action, and intestinal inflammatory responses, preservation of normal gastrointestinal flora, maintenance of antibacterial effects (by alteration of local pH, nutrient competition, modification of pathogen-derived toxins, and stimulation of epithelial mucin production) (10). Probiotic components are used in several forms, such as fortified dairy drinks and food supplements for health benefits. Several studies have shown the role of probiotics administration in numerous infectious illnesses such as wound infections, abscesses, endocarditis, bacteremia, and pneumonia (23-30).

Probiotic components are used in many cultures for health benefits (10). These bacterial components can be a precious additive against increasingly antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Moreover, they are easy, cheap, and available (10).

Recent studies demonstrated that administrating probiotics to patients with mechanical ventilation leads to reducing the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia and the incidence of all nosocomial infections (31, 32). Given that most studies have assessed the role of probiotics for the prevention of respiratory infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in intensive care unit (32, 33) and few studies have found the efficacy of probiotics in reducing bacterial pneumonia, and no comprehensive study has been conducted in this regard in our region, the aim of the current study was to evaluate the role of probiotics in bacterial pneumonia.

2. Methods

2.1. Selecting of Patients

This double-blind, randomized clinical trial study was conducted on patients diagnosed with bacterial pneumonia in Shahid Beheshti Hospital, Kashan, Iran, in 2018. After obtaining informed consent from the patients, the current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences, and 100 patients with bacterial pneumonia were enrolled.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Age over 12 years and clinical diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia based on clinical criteria, including fever, pleural chest pain, cough, tachypnea, presence of parenchymal involvement in chest radiography, and shortness of breath, were considered the inclusion criteria. Heart failure and other diseases that cause lung edema or other pulmonary disorders were considered the exclusion criteria. Moreover, intolerance or allergy to probiotics, unwillingness to participate in the study, and no hospitalization in the intensive care unit (ICU) were other exclusion criteria.

2.3. Classifying of Patients into the Intervention and Control Groups

Patients were randomly classified into two groups (n = 50). The first group received two sachets of probiotic/daily for 5 days. Each probiotic sachet included probiotic strains such as, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium infantis, Streptococcus thermophiles, and Prebiotics such as Fructo-oligosaccharide (Biology fermentation company), and the second group received placebo (Farabi company). Moreover, all patients in the pediatric ward received ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg once daily) and patients in the infectious ward received ceftriaxone (1g/12 hours) with azithromycin.

2.4. Extraction of Data

Data, including age, gender, duration of symptoms before hospitalization, duration of dyspnea, duration of tachypnea, duration of cough, duration of fever, duration of hospitalization and crackles, were extracted from medical records.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered SPSS, version 16. Chi-square test and independent t-test were used for analysis of data. P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the comparison of two groups (case and control groups) in terms of gender.

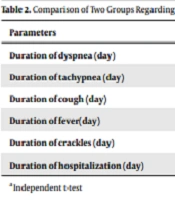

As demonstrated in Table 1, no significant difference was observed between the two groups, regarding gender (P > 0.05). Moreover, the mean age of the patients in the case and control groups was 41.46 ± 18.12 and 44.82 ± 21.39, respectively (P = 0.39). However, no significant difference was seen between the case (5.62 ± 2.09) and control groups (5.78 ± 2.08), regarding the duration of symptoms before hospitalization (P = 0.70). These findings showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of sampling. This implies a completely random classification into two groups. Table 2 shows the comparison of the two groups regarding the characteristics of the patients.

| Parameters | Probiotic (Case) | Placebo (Control) | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of dyspnea (day) | 2.02 ± 1.54 | 3.50 ± 2.13 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of tachypnea (day) | 1.76 ± 1.22 | 3.14 ± 1.85 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of cough (day) | 3.78 ± 1.64 | 4.98 ± 2.23 | 0.002 |

| Duration of fever(day) | 1.86 ± 1.17 | 2.48 ± 1.72 | 0.042 |

| Duration of crackles (day) | 3.04 ± 1.42 | 4.66 ± 1.95 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization (day) | 4.16 ± 1.77 | 5.34 ± 2.37 | 0.005 |

aIndependent t-test.

As shown in Table 2, a significant difference was seen between the two groups regarding duration of hospitalization, dyspnea, tachypnea, cough, fever, and crackles (P <0.05).

4. Discussion

Probiotic components are used in many cultures for health benefits. These products can be a valuable additive against antibiotic-resistant pathogens. They have numerous antibacterial and immunomodulatory actions (10). Most studies have assessed the function of probiotics in ventilator-induced pneumonia prevention. Zarrinfar et al. assessed the role of probiotics in the prevention of ventilator-induced pneumonia. The finding of this study showed that the use of probiotics decreases ventilator-associated pneumonia, as well as the mean days of admission in ICU and hospital (34). They believed that this therapy should be used in the patient's candidate for long-term intubation. Zeng et al. evaluated the effect of probiotics in the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Their findings showed that treatment with probiotics is an effective and safe method for the prevention of VAP (35). Banupriya et al. achieved the same results and reported that probiotics administration reduced the incidence of VAP in critically ill children (36).

Our study showed that the duration of dyspnea, tachypnea, cough, crackles, and duration of hospitalization were decreased in case groups compared to the control group. Given that the mean length of stay for pneumonia in our study was five days and these patients were discharged from hospital 24 to 48 hours after ceasing fever, cough, and shortness of breath, and access to these patients was difficult after discharge, the mean probiotic intake was considered five days. Li et al. assessed characteristics of patients receiving probiotics and observed that probiotics improve the efficacy of amoxicillin against breathing pneumonia (37). Moreover, they observed that cough, fever, and tachypnea were decreased in patients receiving probiotics in comparison to the placebo group. The findings of this study were consistent with the findings of the present study. Siempos et al. reported that administration of probiotics was effective in the prevention of nosocomial pneumonia, duration of hospitalization in ICU, and colonization rate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the respiratory tract (38). Pitsouni et al. showed that probiotics decreased the occurrence of pneumonia and infectious complications as well as the duration of hospitalization (39).

The findings of this study were also consistent with the findings of our study. Wang et al. reported that the probiotic component decreases the incidence of respiratory tract infections in children (40). Shida et al. reported that daily intake of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota with fermented milk may decrease the risk of upper respiratory tract infections by modulation of the immune system in healthy middle-aged (41).

Heidarian et al. showed that the beneficial effect of probiotics on preventing nosocomial infections is more prominent in patients who are hospitalized over 72 hours in hospital (42). Ling et al. evaluated the effect of probiotics in the prevention of pneumonia in children and did not observe antibiotic-associated diarrhea and other adverse events in these children. Moreover, they observed that the use of probiotics is effective in preventing complications in children treated with azithromycin (43). Wolvers et al. reported that probiotics may decrease different symptoms of respiratory tract infections, including ear, nose, and throat infections in children and adults (7). Accordingly, the use of probiotics is considered a promising therapy for infection.

Watkinson et al. demonstrated that the use of pre-, pro-, or synbiotics was not related to the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia in all subgroups; however, the risk of reduction with probiotics was considerable (44).

Other study reported., reported that probiotics, compared to placebo, have better efficacy in the treatment of upper respiratory tract acute infection episodes, which leads to a decrease in the use of antibiotics (45). Moreover, they reported that probiotics could operate against pathogenic bacteria via creating antimicrobial agents such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocin (14, 46, 47), competing for cellular adhesion sites and preventing the production of viral factors. In addition, these components can be effective against pathogens through interacting with the host, reinforcing the action of the epithelium barrier, and changing the immune system answer (14, 46, 47).

Li et al. found that probiotics in combination with amoxicillin-sulbactam are more effective in the treatment of childhood breathing pneumonia (37). Guo et al. reported that oral administration of probiotics reduces pneumonia, while increases pulmonary functions without severe adverse effects. Moreover, no significant difference was seen between patients receiving probiotics than patients receiving placebo in terms of incidence of adverse events (48). On the other hand, Box et al. assessed the effect of lactobacillus probiotics on the rate of Clostridium difficile infection in patients receiving antibiotics and did not observe a difference between those who received probiotics and those who did not receive probiotic in terms of the infection (49). It seems that the dosage of medication, duration of the treatment, type of probiotics, and type of the disease are the reasons for the difference between various studies.

In our study, although we did not evaluate the mechanism of probiotics, Ashraf et al. reported that the use of probiotic supplementation can prevent immune-mediated diseases during childhood. Nevertheless, this intervention during pregnancy can affect fetal immune parameters, including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1) level, cord blood interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) level, and breast milk immunoglobulin A (IgA). It seems that the immune system is stimulated by probiotic microorganisms (50).

Determination of the type of bacterium was not possible in our study; therefore, it may be considered a limitation of the study, but intervention in the two groups was done in the same conditions. In addition, suspected cases of tuberculosis and MDR were excluded from the study. Cases with severe pneumonia that required hospitalization in NICU were not also entered the study to decrease bias in the current study.

4.1. Conclusion

The use of probiotics can be effective in reducing the duration of dyspnea, tachypnea, cough, fever, and length of hospitalization. Therefore, probiotics may be considered a promising treatment for the development of new anti-infectious therapy. In addition, the usage of probiotics, along with antibiotics, is suggested for decreasing pneumonia-associated complications and improving the efficacy of therapy. However, further studies are needed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of probiotics.