1. Background

After more than three decades of discovering the first case of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the disease continues to be one of the most important health, social and economic concerns worldwide (1). AIDS is a chronic and progressive illness in which HIV infects and weakens the immune system (2). In the late stages of the disease, the compromised immune system, as a result of high viral activity and T lymphocytes reduction, predispose the body to the opportunistic infections caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, which are usually not easily occurred in healthy people (3). People living with HIV (PLWH) are also at higher risk of developing concurrent cancers due to the impairment of the immune system (4, 5). Globally, the wide application of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has contributed to a shift in cancer patterns among HIV-infected patients (5-7). Although ART has been effective in HIV treatment, cancers are still responsible for high HIV-related morbidity and mortality (8).

Three decades ago, when highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was not yet well defined and available, AIDS-defining cancers (ADCs) such as Kaposi's sarcoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and cervical cancer were the most common types of cancers among HIV-positive patients (9). According to Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), Burkitt's lymphoma (BL), disseminated large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and plasmablastic lymphoma (PL) are also classified in this category (10). Risk of ADCs has been dropping among HIV patients since 1996; however, non-AIDS-defining cancers (NADCs) among PLWH are still higher than the general population (9).

Currently, in developed countries, the incidence of NADCs is equal to or greater than ADCs in the post-ART era; and NADCs are still one of the main causes of mortality in HIV-infected patients (11). The risk of developing NADCs among PLWH is different and associated with low TCD4+ cell count or late stage of AIDS (12). Therefore, it is important to increase cancer screening and promote early initiation of ART among HIV-infected patients to prevent further immunosuppression (13).

2. Objectives

Characterizing the epidemiology of cancers among HIV-infected patients provides important knowledge that could assist public health professionals and patients to optimize the overall health outcomes (8). Considering that there was no previous study on the prevalence of cancers in HIV-positive patients in Iran, the aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of cancers among PLWH in Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

Our study was a cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of different types of cancers among HIV-positive patients referred to voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) center at Imam Khomeini Hospital, in Tehran; from January 1st, 2004 to August 30th, 2017. A total of 1,243 HIV-positive patients were enrolled in the study. Imam Khomeini Hospital is a referral and well-equipped hospital with a national reputation that HIV-infected patients from across the country visit to seek medical services.

Information on each patient was collected from his/her hospital record. We included all HIV-infected patients who were positive for ELISA as well as Western blot tests. Patients who were diagnosed with cancer five years prior to HIV detection were included in the study; because, according to the study in Iran (14), HIV positive people have been infected with HIV five years before diagnosis with confirmatory tests. However, if another type of cancer different from the previous one was diagnosed in an HIV-infected patient, the sample would remain in the study. Cancer was diagnosed by running pathology and clinical tests in the hospital. The treatments for cancer included chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgery.

3.2. Measurements

This study was reviewed and approved by Tehran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee. Data collection lasted for 3 months and was extracted from patient medical records. These records included information on the prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), types of cancers and other related illnesses, demographic characteristics (age, gender and marital status), the history and type of drug abuse, transmission routes (mother to child, injecting drugs, blood transfusion, and sexual contact), smoking and TCD4+ cell levels at the time of first cancer diagnosis. After reviewing the active records, we contacted the patients and described the goals and necessities of the study; after obtaining informed consent, additional information was collected.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS software version 22 was used for data analysis. The data was organized, and the related variables were extracted from the records. The analyses were performed using the descriptive and inferential statistics; namely, Pearson Chi-square, Fisher's Exact, and Kruskal-Wallis tests, and reporting the crude odds ratios (OR). Subsequently, the adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated using logistic regression model to account for the potential confounding effects of different factors. Variables associated with cancer in bivariate analysis at the P ≤ 0.10 level were included as potential independent predictors. The final model retained those variables associated with cancer at P < 0.05 level.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Patients

A total of 1,243 HIV-infected patients' records from January 1st, 2004 to August 30th, 2017 were retrieved and reviewed. Almost two-third of patients (832 patients) were male. The mean age was 40.5 years old (standard deviation of 11.1). About half of the participants (42.9%) were acquired HIV through heterosexual contact. Approximately 90% of all patients were receiving medical treatment. Demographic information is summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristics | No. (%) | No. Cancer (%) | Odds Ratio | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1243 | 39 (3.1) | ||

| Age group | 0.03a | |||

| ≤ 10 yrs | 33 (2.7) | 1 (2.6) | referent | |

| 11-20 yrs | 18 (1.4) | 1 (2.6) | 1.83 | |

| 21-30 yrs | 97 (7.8) | 1 (2.6) | 0.34 | |

| 31-40 yrs | 462 (37.2) | 12(30.8) | 0.86 | |

| 41-49 yrs | 354 (28.5) | 7 (17.9) | 0.65 | |

| ≥ 50 yrs | 240 (19.3) | 17(43.6) | 2.34 | |

| Gender | < 0.01a | |||

| Women | 411 (33.1) | 23 (59) | referent | |

| Men | 832 (66.9) | 16 (41) | 0.33 | |

| Marital status | 0.02a | |||

| Single | 321 (25.8) | 3 (7.7) | referent | |

| Married | 723 (58.2) | 24 (61.5) | 1.07 | |

| Divorced | 78 (6.3) | 7 (17.9) | 3.16 | |

| Widowed | 42 (3.4) | 4 (10.3) | 10.16 | |

| Educational level | 0.86 | |||

| Illiterate | 146 (11.7) | 5 (12.8) | referent | |

| Elementary to Diploma | 933 (75.0) | 31 (79.5) | 1.11 | |

| Academic | 126 (10.1) | 3 (7.7) | 0.67 | |

| Job | 0.39 | |||

| Retired | 11 (0.9) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Full-time job | 126 (10.1) | 2 (5.1) | referent | |

| Part time job | 279 (22.4 ) | 12 (30.8) | 2.71 | |

| Unemployed | 691 (55.6 ) | 21 (53.8) | 1.92 | |

| Others | 97 (7.8) | 4 (10.3) | - | |

| History of addiction | 0.01a | |||

| Non-injection drug use | 193 (15.5) | 8 (20.5) | referent | |

| Injection drug use | 377 (30.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.63 | |

| How to get HIV | ||||

| Unprotected homosexual relationship | 72 (5.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2.42 | 0.39 |

| Unprotected heterosexual relationship | 533 (42.9) | 23 (59) | 0.55 | 0.07a |

| Drug injection | 338 (27.2) | 5 (12.8) | 2.65 | 0.04a |

| Transfusion | 41 (3.3) | 4 (10.2) | 0.31 | 0.03a |

| Mother-to-child | 42 (3.4) | 1 (2.6) | 1.37 | 0.76 |

| Duration of HIV | 0.09a | |||

| ≤ 5 yrs | 442 (35.6) | 21 (53.8) | referent | |

| 6-10 yrs | 582 (46.8) | 16 (41) | 0.58 | |

| 11-14 yrs | 171 (13.8) | 2 (5.1) | 0.25 | |

| ≥ 15 yrs | 8 (0.6) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Addiction status (at present) | ||||

| Injection use | 151 (12.1) | 1 (2.6) | 5.45 | 0.03a |

| Non-injection use | 237 (19.1) | 4 (10.3) | 2.15 | 0.12 |

| Drugs reported ever used | ||||

| Opium | 136 (10.9) | 2 (5.1) | 2.36 | 0.18 |

| Heroin | 197 (15.8) | 3 (7.7) | 2.35 | 0.11 |

| Morphine | 22 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0.67 | 0.23 |

| Hashish | 18 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.81 | 0.28 |

| Amphetamine | 18 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.81 | 0.28 |

| Methamphetamine | 102 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 0.14 | < 0.01a |

| History of HCV | 272 (21.9) | 3 (7.7) | 0.29 | 0.01a |

| Other diseases | 936 (75.3) | 30 (76.9) | 1.1 | 0.81 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | 1107 (89.1) | 39 (100) | 0.09 | 0.01a |

| Duration of antiretroviral therapy | 0.13 | |||

| ≤ 5 yrs | 523 (42.1) | 22 (56.4) | referent | |

| 6-10 yrs | 505 (40.6) | 17 (43.6) | 0.8 | |

| 11-14 yrs | 69 (5.6) | 0 (0) | - | |

| ≥ 15 yrs | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Name of cancer | ||||

| Cervical cancer | 14 (1.1) | 14 (35.9) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 7 (0.6) | 7 (17.9) | ||

| Kaposi's sarcoma | 4 (0.3) | 4 (10.3) | ||

| Brain | 2 (0.2) | 2 (5.1) | ||

| Breast and ovary | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Colon | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Endometrium & ovary | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Endometrium | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Esophageal cancer | 2 (0.2) | 2 (5.1) | ||

| Lung | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 2 (0.2) | 2 (5.1) | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (0.08) | 1 (2.6) |

astatistically significant.

4.2. Prevalence of Cancer and the Associations

Thirty-nine out of 1243 HIV-infected patients were diagnosed with concurrent cancer, accounting for 3.1% of the study population. Sixteen were male, and 23 were female. The mean age at diagnosis for cancer was 40.1 years old (standard deviation of 13.2). Cancer was diagnosed in a patient one year prior to HIV diagnosis (0.1%), and in 12 patients, cancer and HIV were diagnosed at the same time (2.1%). Of all patients, 2% was diagnosed with ADCs, and 1.1% was diagnosed with NADCs. The distribution was 1.1% cervical cancer, 0.6% non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and 0.3% Kaposi's sarcoma. Almost 54.0% of HIV-infected patients with cancer were diagnosed with HIV within the past five years. The incidence of cancer was approximately 4.8 years after the diagnosis of HIV (standard deviation of 2.2), and the mean TCD4+ count at the time of cancer diagnosis was 294.3 cells/µl. Of these patients, a child died because of a brain tumor and a woman due to a colon tumor. The distributions of cancer in HIV-infected patients are summarized in Table 1.

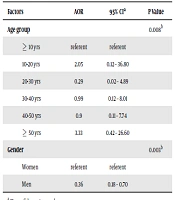

In multivariate analysis that included all variables associated with cancer at P ≤ 0.10 in bivariate analysis, age group (AOR 3.33 for age group ≥ 50 yrs, 95% CI: 0.42-26.60) and gender (AOR 0.36 for men, 95% CI: 0.18–0.70) remained independently associated with cancer (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Moreover, medication information is shown in Table 3.

aCI, confidence interval.

b statistically significant.

| Medication Name | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Lamivudine /efavirenz/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate /vonavir | 3 (0.2) |

| Lamivudine /kaletra/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | 3 (0.2) |

| Lamivudine /nevirapine /zidovudine | 3 (0.2) |

| Zidovudine | 3 (0.2) |

| Zidovudine /efavirenz /kaletra | 3 (0.2) |

| Efavirenz /truvada | 3 (0.2) |

| Kaletra/cobavir | 3 (0.2) |

| Lamivudine /zidovudine | 4 (0.3) |

| Lamivudine /nevirapine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | 4 (0.3) |

| Lamivudine /zidovudine /efavirenz /truvada | 4 (0.3) |

| Atazanavir/kaletra/ritonavir | 4 (0.3) |

| Kaletra/atazanavir/ritonavir | 4 (0.3) |

| Lamivudine / tenofovir disoproxil fumarate /vonavir | 5 (0.4) |

| Lamivudine /nevirapine/tenofovir disoproxilfumarate /cobavir | 6 (0.5) |

| Lamivudine /zidovudine/efavirenz /truvada/vonavir | 6 (0.5) |

| Nevirapine | 7 (0.6) |

| Truvada | 7 (0.6) |

| Lamivudine /efavirenz | 8 (0.6) |

| Lamivudine /zidovudine /kaletra | 8 (0.6) |

| Lamivudine /efavirenz /zidovudine | 9 (0.7) |

| Lamivudine /tenofovir disoproxil fumarate /kaletra | 12 (1.0) |

| Lamivudine /zidovudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate /vonavir | 13 (1.0) |

| Truvada/efavirenz | 14 (1.1) |

| Lamivudine/efavirenz/zidovudine | 18 (1.4) |

| Lamivudine/efavirenz/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | 48 (3.8) |

| Zidovudine/lamivudine/nevirapine | 116 (9.3) |

| Lamivudine /zidovudine /efavirenz | 322 (25.8) |

| Vonavir | 406 (32.6) |

| Total | 1247 (100) |

The associations between multiple variables, including age, gender, duration of HIV infection, duration of ART, concomitant diseases, history of addiction, type of transmission, and TCD4+ levels, with type of cancer were examined, and only the age group between 30-40 years old, had a significant association with AIDS-related cancers (P value = 0.048).

5. Discussion

The present study is the first to investigate the prevalence of cancers in HIV-positive patients in Iran. Thus, the purpose of this study was to achieve a clear epidemiological perspective on cancer prevalence among HIV-infected patients. Since factors such as low TCD4+ count, old age, compromised immune system, smoking and alcohol, presence of associated illnesses and oncogene agents could contribute to the incidence of cancer (15, 16); in this sense, we further examined the association between these factors and existent cancers in HIV-positive population.

Out of 1,243 HIV-infected patients, 39 had concurrent cancer as follows: 14 women with cervical cancer (35.9%), 7 patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (17.9%), and 4 patients with Kaposi's sarcoma (10.3%). Among NADCs, the incidence of esophageal cancer and Hodgkin's lymphoma was 5.1%; other cancers including brain, breast, ovarian, colon, lung, acute myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, and endometrial cancer occurred with the same prevalence rate of 0.08%.

Data from the Ministry of Health in 2018 indicated that the most common malignancies in the Iranian population belong to the gastrointestinal tract, including stomach, colon, esophagus, and pancreas (27%), followed by breast (12%), lung and laryngeal (7.5%), kidneys, urinary tract and bladder (7%) (17). However, in our HIV-positive population, the results were different compared to the national pattern of cancers in Iran.

According to the American Comprehensive Cancer Network report; in PLWH, the risk of cervical cancer is approximately 3-5 times, anal cancer is about 25 to 35 times, lung cancer is 2 to 5 times, and Hodgkin's lymphoma is 4 to 5 times higher than that of the general population; the incidence of anal cancer is about 10%, lung cancer is 11%, and Hodgkin's lymphoma is about 4% (18).

In the present study, any anal cancer was found and the number of women identified with cervical cancer was higher than other HIV-related cancers. This may be due to the regular screening of women with HIV in the VCT centers. Consistent with this study, Barnes et al. found that screening could have a significant effect on disease identification. According to Barnes, 56% of enrolled women did not have any evidence of cervical cancer in the primary pap smear test. However, during the study and after follow-up, 21 patients were diagnosed with high-grade dysplasia and three patients with cervical cancer (19). This proved the importance of regular screening and follow-up of patients. Barnes study also reported that all HIV-positive patients with Kaposi's sarcoma were male. Another study, conducted by White et al., between 2000 and 2014, showed that 12,549 of HIV-infected individuals were diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma and most of whom (95%) were men aged 20 to 54 years. It also showed that the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma dropped from 1.4% in 2000 to 0.95% in 2014 (20). Based on these results, the effect of gender on Kaposi's sarcoma could be suggested.

All HIV-positive patients were treated with ART drugs once they were diagnosed with HIV (except for one patient who was not treated at all) in the present study. The mean of TCD4+ count at the time of the diagnosis of cancer in the affected population was 294.3 cells/µl; this rate was not evaluated over time. However, to examine the effect of this variable, there was a need for sequential measurement of TCD4+ cells. In Lee et al. study, the incidence of cancer in the first ten years of HIV infection was very high in those with viral load between 200 and 999 copies/ml during the first six months of ART. However, after controlling the effective factors, there was no correlation between cancer and the amount of RNA virus after six months of treatment initiation (21).

In the present study, mortality was limited to two NADCs patients. Since diseases such as human HPV-8 virus (HHV-8), human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B and C virus (22, 23), and Epstein Barr virus play important roles in the pathogenesis of cancer in HIV-positive patients (24), the study of associated illnesses in HIV-positive individuals is of great importance. In this study, in HIV positive people with cancer, the incidence of hepatitis B was 2.6%, hepatitis C was 7.7%, HPV infection was 2.6%, and no participants had herpes simplex virus (HSV).

In the current study, the incidence of various types of cancers was not evaluated over time in HIV-infected patients; however, several studies suggested that effective ART would reduce the incidence of ADCs. In a study performed by Shils et al., the incidence of cancer in HIV-infected patients by 2030 was predicted using statistical software. It predicted that Kaposi's sarcoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin's disease, cervical cancer, lung cancer, and colon cancer would reduce in people older than 65 years old; whereas, the incidence of prostate cancer would increase. Prostate and lung cancers were predicted as the two most common cancers among HIV-positive people by 2030 (25). According to Ressler et al., the AIDS-related mortality rate halved between 1995 and 2017, while the proportion of deaths from non-ADCs increased. In addition, the results showed that patients with NADCs had higher mean age, higher TCD4+ count, and higher viral load. Most of the cases were male, and 80% of them were smokers (26).

In a retrospective study in Romania between 2010 and 2016, 110 cancer patients were identified among HIV-positive patients, while the incidence of ADCs declined from 1.6% to 0.3%, non- ADCs remained constant at 0.3% during that period. It also showed that high levels of TCD4+ and low levels of viral RNA were associated with long-term survival in the ADCs group, but not in the NADCs group (27). Similar results in the study performed by Hasswell et al., (1996- 2013) showed that the mortality rate among the ADCs group decreased, whereas this rate increased among the NADCs group (28). Other studies reported that, although the incidence of ADCs declined in recent years, as the HIV-infected population aged, the incidence of NADCs increased and had the same incidence to the general population (12, 29-32). As a result, a proper screening program and early vaccination against preventable oncogenesis seem to be of substantial importance (24).

In addition, the associations between the variables were evaluated, and there was a significant correlation with the type of cancer in the age group of 30-40 years (P = 0.048). According to Shiels study, the age of diagnosis of many cancers in HIV-positive patients was lower than the normal population, which was twenty years (33). Furthermore, in another study by Shiels, the prevalence of AIDS-related cancers between 1991 to 2005 declined among 20-39 years. On the contrary, the burden of non-AIDS-related cancers in people over 40 years old has increased, which is not consistent with the results of this study (34).

Unfortunately, it was not possible to collect data on as many variables as may have been needed for the study. Since patients did not provide us with all the information needed due to stigma, we could not measure some variables such as smoking or alcohol use. Moreover, the population of the study was limited to those referring to governmental hospitals, and patients who were treated in private hospitals or received no treatment were not enrolled. A further multi-center study with a larger sample size is recommended to investigate the concurrence of cancers among HIV-infected patients over the years. The prevalence of ADCs was higher than NADCs patients in our study. Both screening and early initiation of ART were vital factors in the early diagnosis and treatment of different types of cancer in PLWH.