1. Background

Salivary nitric oxide (s-NO) concentration is one of the markers for respiratory inflammation, such as asthma (1). Excessive s-NO production is associated with various oral diseases such as Sjögren syndrome and periodontitis (2, 3). The s-NO concentration may be a physiological marker for systemic conditions (4, 5) because acute whole-body exercise can induce a s-NO response (4, 6). However, there have been conflicting results on whether acute aerobic exercise increases s-NO production (4, 6) or not (7). This may be due to differences in exercise intensity because the chronic response of s-NO showed a proportional response to the intensity of the training (8). However, no previous studies have investigated the acute effects of exercise intensity on s-NO responses.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effect of exercise intensity on the s-NO response at the same exercise duration. Our hypothesis was that the s-NO responses differed depending on the exercise intensity, even if the duration of exercise was the same.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

We enrolled five healthy adult men (21.6 ± 0.9 years, 170.1 ± 5.4 cm, 62.9 ± 5.4 kg) who were non-smokers and had no other diseases or injuries. The fitness level of the participants was recreational, with no regular high-intensity exercise and exercise habits of less than two days a week. The present study was approved by the ethical committees and conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent before being included in the study.

3.2. Design

The participants performed two exercise sessions for 30 min each at different exercise intensities based on a cross-over design, 50% heart rate (HR)reserve (low-intensity condition) and 80% HRreserve (high-intensity condition), using a bicycle ergometer (75XL.; Combi Wellness Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Each exercise was safely performed with no reported adverse events or discomfort during or after exercise sessions. Participants were instructed to refrain from performing intensive exercise and consuming alcohol and caffeine 24 h before the 2 experimental days. They were asked to fast overnight for 12 h, and only water was allowed. Both sessions were conducted in a laboratory maintained at 24 - 26°C. Participants were asked for a subjective evaluation of exercise intensity (rating of perceived exertion (RPE)) using the Borg scale every 5 min during the two experimental exercises. Stimulated saliva samples were collected before (pre), immediately after (post 0-h), and 1 hour after exercises (post 1-h) using a cotton swab (Salivette; Sarstedt Inc., Nümbrecht, Germany) for s-NO concentration. Saliva was collected according to the method described previously (9).

3.3. Assay of Salivary Components

After measuring the saliva flow, samples were frozen at -40°C until analyses. The nitrate concentration, as the s-NO concentration, was assessed using a commercially available colorimetric assay kit (Nitric Oxide detection kit #ADI-917-010, Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis data are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE). Paired sample t-tests were used to examine the difference in the total RPE during exercise between the two intensities. A two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures (time*condition) was used to analyze s-NO. The Bonferroni post hoc test was performed when a significant interaction was observed. A two-tailed P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (ver. 25) (IBM SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

4. Results

All participants completed two different exercise sessions (low and high intensity). No significant differences were found in s-NO concentration between the low- (629 ± 217 µmol/L) and high- (327 ± 133 µmol/L) intensity conditions at pre. s-NO concentrations were post 0-h (640 ± 208 µmol/L), post 1-h (694 ± 200 µmol/L) after low-intensity exercise, and post 0-h (572 ± 111 µmol/L), post 1-h (731 ± 94 µmol/L) after high-intensity exercise.

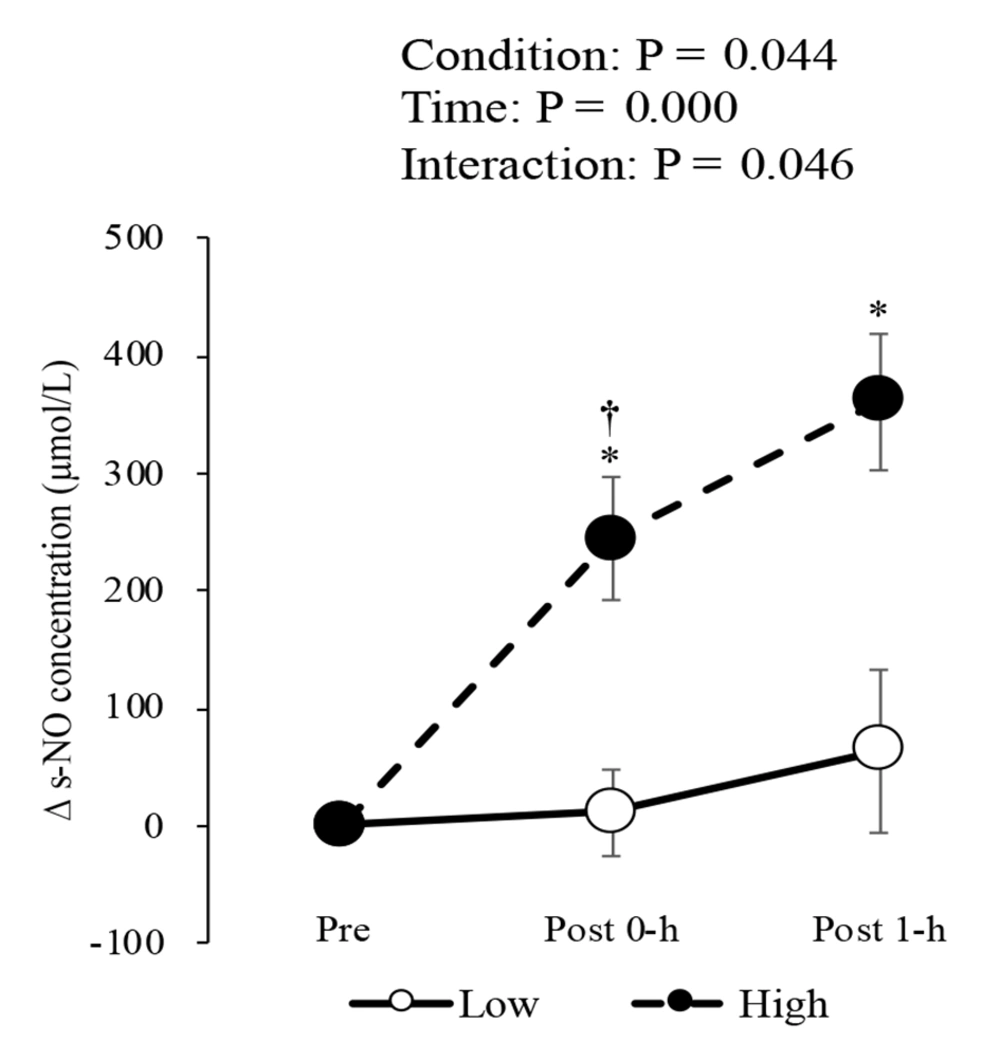

Figure 1 shows the changes in s-NO concentration after high- and low-intensity exercise. A two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures followed by a post hoc test showed a significant interaction (F(2, 8) = 4.639, partial η2 = 0.537) between the two intensities. The post hoc test showed that the s-NO concentration increased significantly at post 0-h (+244 ± 53 µmol/L) and post 1-h (+362 ± 58 µmol/L) after high-intensity exercise compared to that at pre. In contrast, the s-NO concentration after low-intensity exercise did not change at post 0-h (+11 ± 37 µmol/L) and post 1-h (+64 ± 69 µmol/L). At post 0-h, the s-NO concentration was significantly higher after high-intensity exercise than after low-intensity exercise.

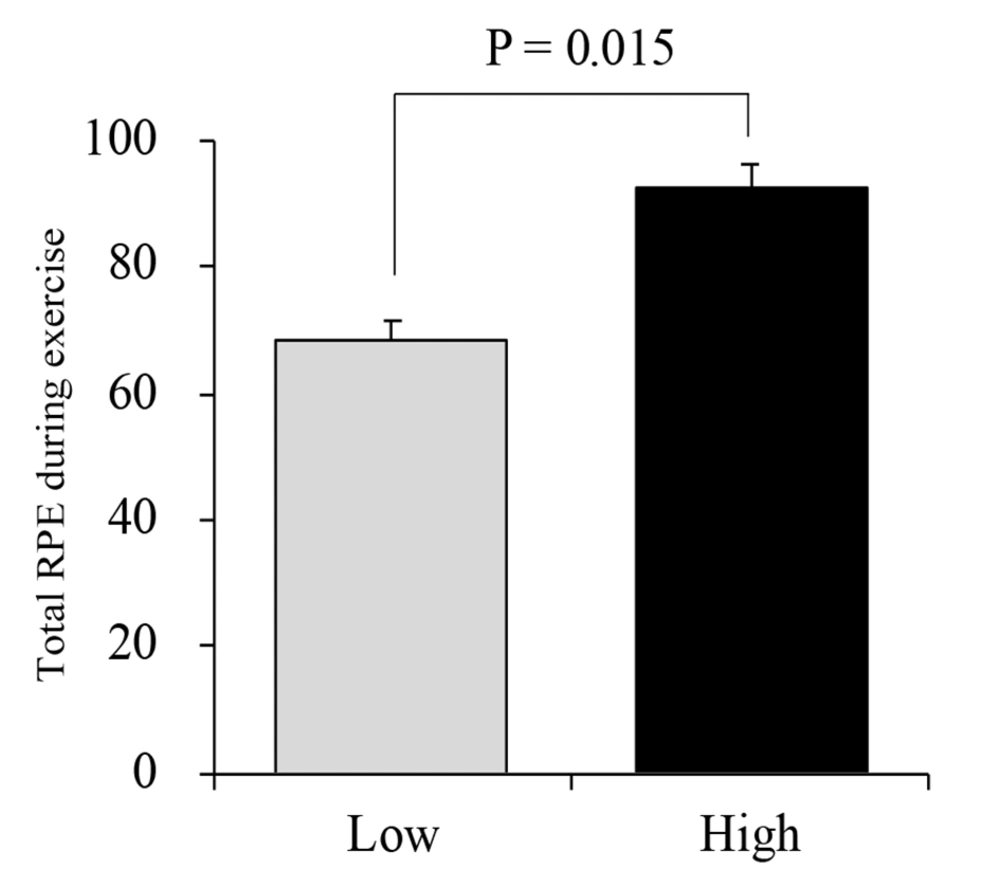

Figure 2 shows the changes in the total RPE during the exercises. The total RPE was higher during high-intensity exercise (92 ± 4) than during low-intensity exercise (68 ± 3).

5. Discussion

This study demonstrated that s-NO production depended on exercise intensity. s-NO concentration did not change during low-intensity exercise but increased substantially during high-intensity exercise.

Ergometer exercise for 30 min at a high intensity of 80% HRreserve increased s-NO concentration after exercise, consistent with the previous findings (4, 6). Moreover, the interaction (time*condition) of s-NO changes was also observed, with a significant difference between low- and high-intensity exercises at post 0-h. Although the sample size was small, the effect size of the s-NO change was large (> 0.50). However, the possibility of type 2 errors due to the small sample size should also be considered. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which plays an important role in the mechanism of s-NO production, is over-secreted from inflamed salivary glands (3, 10), which was not measured in this study. The mechanism by which the difference in exercise intensity affects s-NO production should be further investigated. Exhaled NO, which reflects the inflammatory status of the lower respiratory tract, also needs exploration.

High s-NO levels were reported in individuals with various oral diseases and athletes with a history of asthma (1-3). Increased s-NO concentration after high-intensity exercise in our study might indicate that high-intensity exercise in training strategies increases the risk of inflammation in the oral cavity and lower respiratory tract. In contrast, low-intensity exercise did not affect s-NO concentrations, implying that low-intensity exercise might not increase the risk of oral and respiratory diseases in exercise prescriptions for patients. Since measurements in the present study were only taken up to 1 hour after exercise, it is unclear how long the acute s-NO increase lasts. Observation for a longer time after exercise is required to clarify recovery of the exercise-induced increase in s-NO concentration. Continued high s-NO levels may be a risk factor for developing chronic oral and respiratory diseases. Therefore, for using s-NO as an inflammation marker of oral and respiratory tracts, further study should be investigated, including conventional markers of inflammation such as interleukin-6 (IL-6).

In conclusion, our study indicates that s-NO responds differently in the acute phase depending on the exercise intensity.