1. Background

Extensive research shows that dietary antioxidants could protect body cells against free radicals. Ubiquinone, also known as coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10, 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-decaprenyl benzoquinone), is an important endogenous cellular antioxidant (1). The human body and other living organisms, normal cellular metabolism, and environmental factors, such as air pollutants, can produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). This process which disturbs the balance between oxidants and antioxidants, is called oxidative stress (OS). The OS can cause damage to cell structures such as carbohydrates, nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins functions and contributes to the development of many diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and so on (2, 3). In addition to the natural process of producing oxidative stress in the body, cells exercising with different intensities can induce oxidative stress, leading to fatigue, muscle damage, and impaired performance (4). Despite the many known health benefits of exercise, evidence shows that resistance and endurance exercise causes oxidative stress. During the mentioned activities, the body's oxygen consumption increases, which produces more ROS in the body. Since the amount of ROS produced exceeds the body's ability to detoxify them, some of them remain in the body and cause oxidative injury (5, 6). With the increase in aerobic exercise intensity, these damages will be increased (6). Numerous studies have shown the effect of coenzyme Q10 on oxidative stress and its ability to scavenge against various free radicals (7-11). This supplement can reduce cellular oxidant activities in normal conditions, exercise-induced oxidative stress in damaged muscle, and improve various aspects of exercise performance at different intensities (4). Coenzyme Q10 is poorly absorbed in electrons; as a result, it loses one or two electrons and is easily oxidized. The coenzyme Q10 is a powerful antioxidant characterized by the rapid uptake and loss of electrons (12). Coenzyme Q10 inhibits the production of free radicals (13). Coenzyme Q10 regenerates vitamin E from α-tocopherol radicals (14). OS overproduction of reactive oxygen species is an important factor in developing diseases (ROS) (8). OS reveals an imbalance between ROS and the ability to repair the damage. Instabilities in the normal redox state of cells can cause toxic effects by producing free radicals that damage all components of the cell, including DNA. OS causes base damage and DNA strand breaks (15). The dietary composition can alter antioxidant mechanisms (16). Many randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and a few systematic reviews have investigated the impact of CoQ10 on oxidative stress (8, 17-19), but the results of systematic reviews about the effect of CoQ10 supplementation on oxidative stress seem to be inconclusive.

2. Objectives

The effects of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) supplementation on OS parameters were assessed through an updated systematic review and meta-analysis.

3. Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched using the following keywords:

Glutathione Reductase OR Glutathione Peroxidase OR Superoxide Dismutase OR Nitric Oxide OR Oxidative Stress OR Malondialdehyde OR Total Antioxidant Capacity OR Total Antioxidant Status OR antioxidant OR Oxidant OR reactive oxygen species OR ROS OR Catalase OR reactive nitrogen species OR protein carbonyl) AND (Coenzyme Q10 OR "Q10" OR CoQ10 OR Ubiquinone OR Bio-Quinone Q10 OR Ubisemiquinone radical OR Ubisemiquinone OR Ubiquinol-10 OR Ubiquinol.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The independent reviewers selected two randomized placebo-controlled studies on adults (18 years or older) that evaluated the effects of CoQ10 on malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH), nitric oxide (NO) levels, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities, and total antioxidant capacity (TAC), and were published between 2000 and 1st May 2022.

3.3. Data Extraction

Two authors performed data extraction and quality assessment of included studies independently. First author's name; type of participant disease; sample size; year of publication; the dose and duration of supplementation; age; body mass index (BMI); gender of participants; and outcome variables (CAT, TAC, MDA, GPx, GSH, NO, and SOD).

3.4. Assessment of Quality

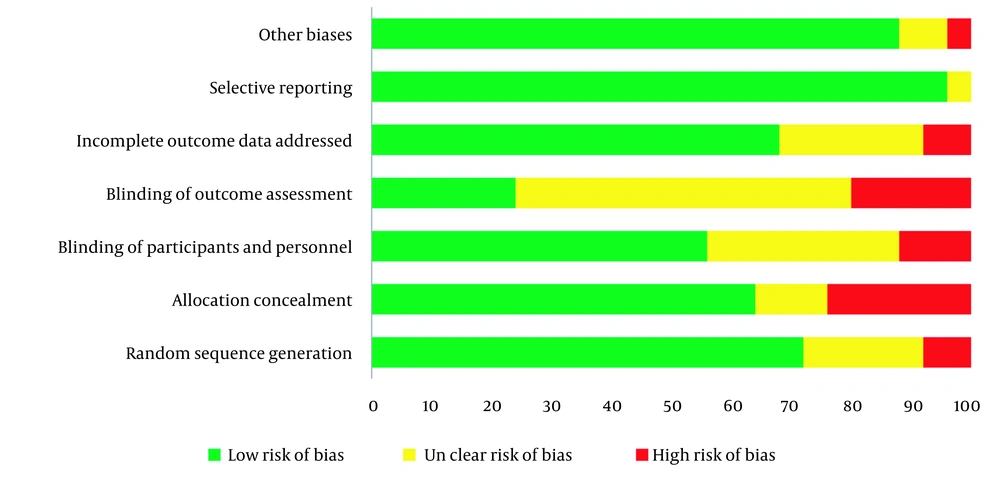

The Cochrane risk of a bias assessment tool which assesses the adequacy of randomization sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, attrition bias, and other potential sources of bias, was used for quality assessment.

3.5. Statistical Analysis and Data Synthesis

Firstly, the mean changes from the baseline to the end of the study period were extracted for each included study. In the second step, the correlation coefficient was calculated separately for the experimental and control groups as follows:

The SD changes from the baseline calculated using the correlation coefficient for each group separately as follow:

Cochran's Q test and I2 statistics were used to assess the heterogeneity between the studies. A high amount of I2 (more than 75%) refers to the presence of heterogeneity. The random-effects DerSimonian and Laird model was used to calculate the pooled mean difference according to significant heterogeneity between studies. The publication bias was assessed by Begg's and Egger's tests. Moreover, the heterogeneity between the studies was determined via meta-regression analysis. The significance level for Begg's and Egger's tests was 0.1, and for other tests, 0.05 was considered a significant level. All analyses were done using STATA software version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

4. Results

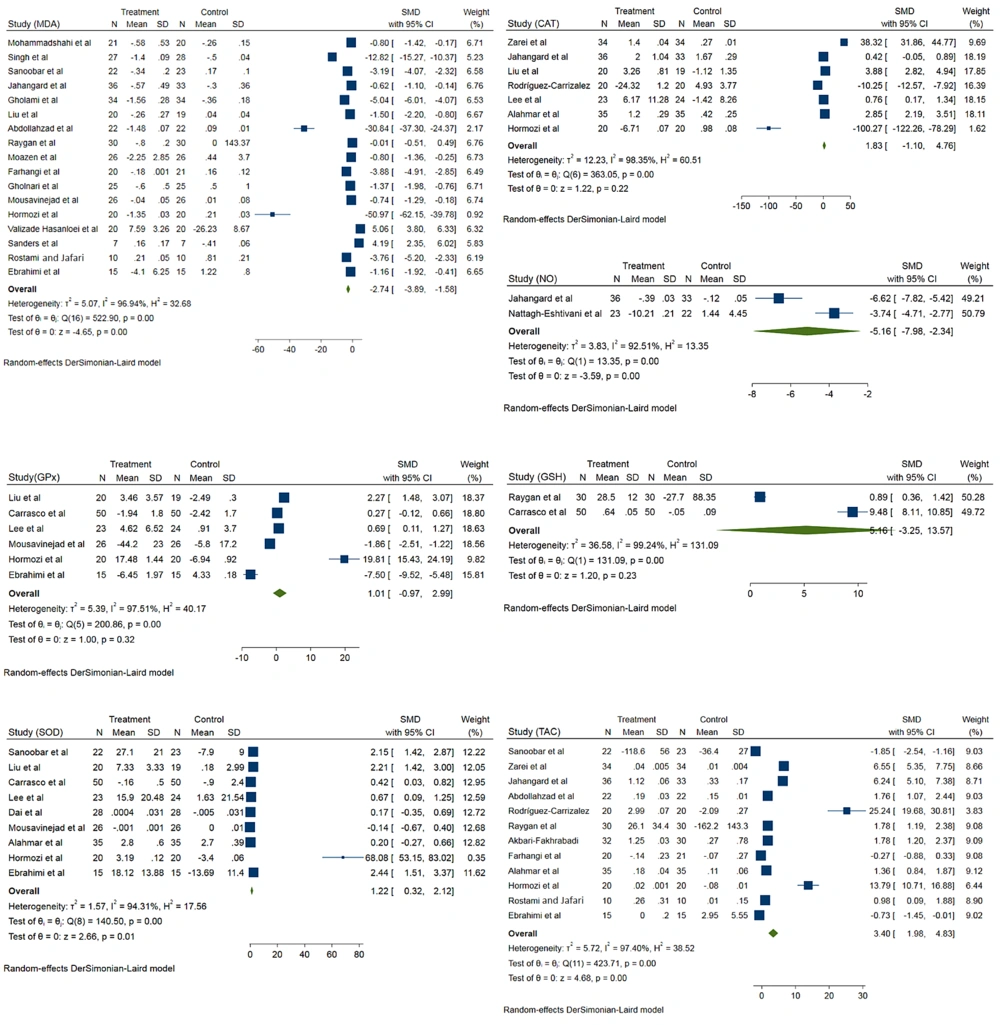

4.1. Study Selection Process

Searching electronic databases led to 4158 records. Firstly, the found studies were screened using the title, abstract or full text. In this step, 274 articles were assessed for eligibility using the full text. Of these, 25 RCTs had inclusion criteria used for the final analysis. The screening steps of the studies are presented in Figure 1. The total of understudied cases in the studies was equal to 1169 people. The range of sample sizes varied from 20 to 100. Most of the studies were performed in Iran (16 papers). The doses of CoQ10 prescribed in the included studies were from 30 to 400 mg per day, and the duration of supplement administration in different studies was between 1 and 24 weeks. More detail is shown in Table 1.

| First Author | Country | Year | Population | Dose of Q10 | Sample Size | Duration (Weeks) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammadshahi et al. (19) | Iran | 2014 | Fatty liver disease patients | 100 mg/kg /body weight | 41 | 12 | MDA↔ |

| Singh et al. (18) | India | 2018 | Acute coronary syndrome | 120 (mg/day) | 55 | 12 | TBARS↓, MDA↓ |

| Sanoobar et al. (8) | Iran | 2013 | MS | 500 (mg/day) | 48 | 12 | MDA, TAC, SOD, GTx |

| Zarei et al. (20) | Iran | 2018 | DM | 100 (mg/day) | 68 | 12 | CAT↑, TAC↑ |

| Jahangard et al. (21) | Iran | 2019 | Bipolar disorders | 200 (mg/day) | 69 | 8 | ↔MDA, ↔CAT, ↑TAC, ↓NO |

| Gholami et al. (22) | Iran | 2018 | T2DM | 100 (mg/day) | 68 | 12 | MDA↓, 8-Isoprostane↓ |

| Nattagh-Eshtivani et al. (23) | Iran | 2018 | Migraine | 400 (mg/day) | 46 | 12 | MMP-9↓, NO↓ |

| Liu et al. (24) | Taiwan | 2015 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 300 (mg/day) | 39 | 12 | MDA↑, SOD↑, CAT↑, GPx↑ |

| Abdollahzad et al. (25) | Iran | 2015 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 100 (mg/day) | 44 | 8 | TAC↔, MDA↓ |

| Rodriguez-Carrizalez al. (26) | Mexic | 2016 | T2DM | 400 (mg/day) | 60 | 24 | TAC↔, CAT↑, GTx↑ |

| Raygan et al. (27) | Iran | 2015 | T2DM | 100 (mg/day) | 60 | 8 | TAC↔, MDA↓, GSH↑ |

| Moazen et al. (28) | Iran | 2015 | T2DM | 100 (mg/day) | 52 | 8 | MDA↓ |

| Akbari Fakhrabadi et al. (29) | Iran | 2014 | T2DM | 200 (mg/day) | 62 | 12 | TAC↑ |

| Carrasco et al. (30) | Spain | 2014 | Renal injury | 200 (mg/day) | 100 | 1 | SOD↔, GPx ↔, GSH↔ |

| Farhangi et al. (10) | Iran | 2014 | NAFLD | 100 (mg/day) | 41 | 4 | MDA↓, TAC↑ |

| Lee et al. (31) | Taiwan | 2013 | CAD | 300 (mg/day) | 42 | 12 | SOD↑, CAT↑, GPx↑ |

| Dai et al. (32) | Hong Kong | 2011 | Ventricular dysfunction | 300 (mg/day) | 56 | 8 | SOD, 8-isoprostane↔ |

| Gholnari et al. (11) | Iran | 2018 | Diabetic nephropathy | 100 (mg/day) | 50 | 12 | MDA↓ |

| Mousavinejad et al. (9) | Iran | 2018 | Autism | 30 (mg/day) | 52 | MDA↓, SOD↓, GPx↓ | |

| Alahmar et al. (33) | Iraq | 2020 | Idiopathic infertility | 200 (mg/day) | 70 | 12 | TAC↑, SOD↑, CAT↑ |

| Hormozi et al. (34) | Iran | 2019 | Glazers with occupational cadmium exposure | 120 (mg/day) | 40 | 8 | MDA↓, TAC↔, SOD↑, GPx↑ , CAT↓ |

| Valizade Hasanloei et al. (35) | Iran | 2021 | ICU patients | 400 (mg/day) | 40 | 1 | MDA↓ |

| Sanders et al. (17) | USA | 2020 | Type II diabetes non-random | 200 (mg/day) | 14 | 2 | MDA↓ |

| Rostami and Jafari (36) | Iran | 2010 | Inactive men | 20 | 2 | TAC↓, MDA↔, | |

| Ebrahimi et al. (37) | Iran | 2019 | MS women | 300 (mg/day) | 30 | 8 | MDA↔, SOD↓, GPx↔, TAC↔ |

4.2. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Oxidative Stress Parameters

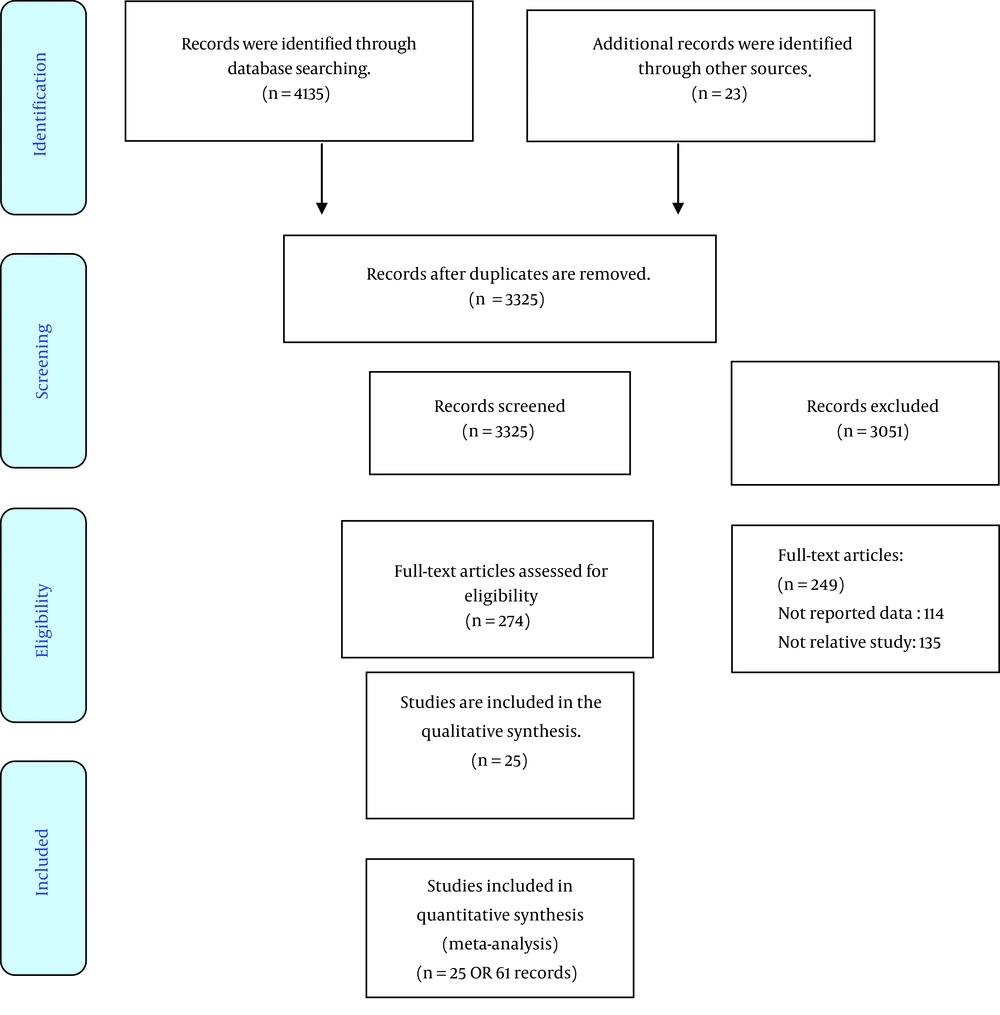

The MDA level was evaluated in 17 records. Coenzyme Q10 significantly reduced MDA levels in the intervention group compared to the control group (standardized mean difference (SMD) - 2.74; 95% CI -3.89, -1.58; I2 = 96.9%) (Figure 2). Results showed that CoQ10 significantly reduced MDA levels in patients younger than 50 years (SMD -8.24; 95% CI -10.91, -5.57; I2 = 97.5%). The intervention dose not significantly decrease MDA levels among patients older than 50 years (SMD -0.23; 95% CI -1.42, 0.95; I2 = 96%). Results showed that in patients with BMI < 25, CoQ10 supplementation significantly decreased MDA levels (SMD -7.53; 95% CI -10.87, -4.19; I2 = 97. 5%). The intervention also significantly decreases MDA levels among patients with BMI ≥ 25 (SMD -1.55; 95% CI -2.37, -0.32; I2 = 96.67%). According to different doses, CoQ10 at a dose of less than 200 significantly reduced MDA levels (SMD -5.02; 95% CI -6.64, -3.40; I2 = 97.2%). Also, CoQ10 at a dose of more than 200 did not had significantly effect on MDA levels (SMD 0.37; 95% CI -1.47, 2.20; I2 = 96.5%).

The effects of CoQ10 supplementation on CAT activity were evaluated in seven records. Comparison to control group, CoQ10 does not have significant effects on CAT activity (SMD 1.83; 95% CI -1.10, 4.76; I2 = 98.3%). Also, different doses of CoQ10 supplementation showed the same results, but the results were significant in patients with age > 50 and BMI > 25 (Figure 2).

The effects of CoQ10 supplementation on GPx activity were evaluated in six records. According to pooled analysis, CoQ10 does not have significant effects on GPx activity (SMD 1.01; 95% CI -0.97, 2.99; I2 = 97.5%) (Figure 2). Two studies evaluated the effects of CoQ10 supplementation on plasma NO. According to results, CoQ10 supplementation significantly reduced plasma NO concentrations among intervention groups compared to the control group (SMD -5.16; 95% CI -7.98, -2.34; I2 = 92.5%) (Figure 2).

The effect of CoQ10 supplementation on SOD activity was assessed in nine records. According to a pooled analysis, CoQ10 supplementation significantly increased SOD activity among the intervention groups (SMD 1.22; 95% CI 0.32, 2.12; I2 = 94.32%) (Figure 2). According to a pooled analysis of 20 records, CoQ10 supplementation significantly increased TAC levels among the intervention groups (SMD 3.40; 95% CI 1.98, 4.83; I2 = 97.4%) (Figure 2). About the effects of CoQ10 supplementation on GSH levels, the analysis was not showed a significant difference between intervention and placebo group (SMD 5.16; 95% CI -3.25, 13.57; I2 = 99.2%) (Figure 2).

Table 2 shows each OS indexes overall and stratified pooled SMD estimation. Overall, the risk of bias among understudied papers was low. More than 70% of the included studies met the random sequence generation. However, allocation concealment and blinding were considered in more than 50% of studies (Figure 3).

| Variables | SMD | 95% CI | T2 | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA | ||||

| Age | ||||

| < 50 | -8.24 | -10.91, -5.57 | 12.14 | 97.5 |

| ≥ 50 | -0.23 | -1.42, 0.95 | 3.07 | 96 |

| BMI | ||||

| < 25 | -7.53 | -10.87, -4.19 | 11.9 | 97.5 |

| ≥ 25 | -1.55 | -2.78, -0.32 | 4.20 | 96.6 |

| Dose | ||||

| < 200 | -5.02 | -6.64, -3.04 | 6.2 | 97.3 |

| ≥ 200 | 0.37 | -1.47, 2.20 | 4.9 | 96.5 |

| Total | -2. 74 | -3.89, -1.58 | 5.07 | 96.9 |

| CAT | ||||

| Age | ||||

| < 50 | -1.95 | -6.28, 2.38 | 10.3 | 98.2 |

| ≥ 50 | 6.64 | 0.31, 12.96 | 12.59 | 98.35 |

| BMI | ||||

| < 25 | -48.56 | -152.69, 55.57 | 558 | 98.8 |

| ≥ 25 | 3.13 | 0.10, 6.15 | 10.31 | 98.43 |

| Dose | ||||

| < 200 | 31.35 | -169.59, 106.89 | 4451 | 99.3 |

| ≥ 200 | -0.10 | -2.19, 1.99 | 5.31 | 97.4 |

| Total | 1.83 | -1.10, 4.76 | 12.6 | 98.3 |

| GPx | ||||

| Age | ||||

| < 50 | 3.91 | -5.2, 13.0 | 62.6 | 98.5 |

| ≥ 50 | 0.37 | -1.92, 2.66 | 3.96 | 97.0 |

| BMI | ||||

| < 25 | 4.67 | -5.40, 14.75 | 77.11 | 98.64 |

| ≥ 25 | -0.29 | -1.67, 1.09 | 1.40 | 94.92 |

| Dose | ||||

| < 200 | 9.04 | -12.6, 3.70 | 241 | 98.9 |

| ≥ 200 | -0.07 | -2.53, 1.14 | 3.2 | 96.3 |

| Total | 1.01 | -0.97, 2.99 | 5.4 | 97.5 |

| SOD | ||||

| Age | ||||

| < 50 | 2.17 | 0.41, 3.92 | 3.14 | 96.4 |

| ≥ 50 | 0.70 | -0.18, 1.58 | 0.7 | 88.25 |

| BMI | ||||

| < 25 | 4.45 | 1.6, 7.3 | 6.4 | 95.9 |

| ≥ 25 | 0.27 | 0.03, 0.52 | 1.62 | 94.3 |

| Dose | ||||

| < 200 | 34.23 | -33.9, 102.4 | 1256 | 98.7 |

| ≥ 200 | 1.13 | 0.47, 1.80 | 0.7 | 88.7 |

| Total | 1.22 | 0.32, 2.12 | 1.57 | 94.3 |

| TAC | ||||

| Age | ||||

| < 50 | 2.23 | 0.57, 3.90 | 5.41 | 97.2 |

| ≥ 50 | 6.57 | 3.57, 9.58 | 8 | 97.5 |

| BMI | ||||

| < 25 | 3.19 | -0.8, 7.2 | 11.7 | 97.9 |

| ≥ 25 | 3.48 | 2.05, 4.90 | 4.25 | 96.6 |

| Dose | ||||

| < 200 | 3.65 | 1.64, 5.65 | 5.7 | 96.9 |

| ≥ 200 | 3.49 | 1.17, 5.80 | 7.47 | 97.0 |

| Total | 3.40 | 1.98, 4.83 | 5.7 | 97.4 |

| GSH | 5.16 | -3.25, 13.57 | 36.5 | 99.24 |

| NO | -5.16 | -7.98, -2.34 | 3.8 | 95.5 |

4.3. Meta-regression Analysis

According to a simple meta-regression analysis, the study year and sample size do not significantly affect heterogeneity between studies about the understudied factors (P > 0.05).

4.4. Publication Bias

According to Begg's and Egger's tests, there was significant publication bias about the CAT, GPx, GSH, and NO. Nevertheless, Egger's test showed publication bias for MDA, SOD, and TAC (P = 0.01, 0.02, 0.003, respectively).

5. Discussion

The current study results are consistent with previous studies (8, 22, 38, 39), showing that supplementation with CoQ10 significantly improves OS parameters. It increases TAC levels and SOD activities and decreases MDA and NO levels. However, this supplementation does not affect GSH or CAT levels. Also, the present study results, in line with other studies, showed that supplementation with CoQ10 does not change GPx activity (40). There are few meta-analyses about the effects of CoQ10 supplementation on OS profile. A meta-analysis by Akbari et al. showed a significant decrease in MDA (39). Another meta-analysis showed that the CoQ10 supplementation increased SOD and CAT while decreasing MDA levels (38). According to our results, CoQ10 supplementation significantly increases SOD in addition to the abovementioned factors. Antioxidant enzymes are the first defense barrier against ROS, and their reduction in the body will lead to increased OS (41). A study has shown that a daily intake of 150 mg of CoQ10 supplementation significantly decreases oxidative stress and increases the activity of antioxidant enzymes (42).

CoQ10 protects cells against apoptosis and OS damage (43). Apoptotic proteins like Bax lead to caspase-induced apoptosis by increasing cytochrome c release (38). On the other hand, anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2, by combining with Bax and reducing the release of cytochrome c, inhibit the apoptotic process (44). Caspase-3 can cause DNA fragmentation and, eventually, apoptosis (45, 46). However, this process was reversed by CoQ10 (47).

Subgroup analyzes of our results show that CoQ10 supplementation significantly increases TAC in overweight and obese individuals. Evidence suggests that obesity-related factors, including hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and increased adipose tissue, are important factors associated with oxidative stress (48).

In addition, our results showed that taking CoQ10 at a dose of > 200 mg daily significantly changed TAC levels. Another study showed that higher doses of CoQ10 may have faster and more stable antioxidant effects (42).

Our study results showed that CoQ10 supplementation also significantly reduced MDA levels. MDA is a polyunsaturated fatty acids peroxidation product (49). Coenzyme Q10 supplementation protects against lipid peroxidation, regulates lipid metabolism, and prevents lipid oxidation (50). Coenzyme Q10 also limits the production of endogenous ROS in mitochondria (8, 51) and is usually related to decreased MDA levels (52). Coenzyme Q10 is the main element of the antioxidant process in all parts of the cells (53) and can reduce ROS and free radicals levels, produced by the reaction with oxygen radicals or lipids through a direct reduction back to the tocopherol, resulting in improvement of oxidative stress (54). Q10 supplementation may reduce plasma lipid peroxidation and regenerate tocopherol radicals (55).

Our systematic review and meta-analysis results, consistent with other studies (34, 56), show that CoQ10 supplementation significantly affected SOD activity. Coenzyme Q10 can play an antioxidant role by reducing ROS in mitochondria, thereby changing SOD activity (57). Despite a nonsignificant difference between intervention and placebo groups, the results of our study showed that CoQ10 supplementation changed CAT activity. The few primary studies may be why we could not find a significant effect of CoQ10 supplementation on CAT activity. This study showed that CoQ10 supplementation improves TAC and MDA concentrations and SOD and NO activity compared with placebo. Finally, CoQ10, as a generally safe and well-tolerated supplement, could be considered for treating and preventing some human disorders. Furthermore, CoQ10 can be used as an important adjuvant in treating different elderly diseases and chronic conditions.

5.1. Conclusions

CoQ10 supplementation significantly reduces MDA and NO concentrations and increases TAC and SOD activity. However, the effects of CoQ10 supplement on NO, GSH concentrations, or CAT activity were not statistically significant. It should be regarded that more interventional studies, such as clinical trials with higher sample sizes, are needed to assess the impact of CoQ10 supplementation on oxidative stress parameters.