1. Context

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) is a transcription factor that belongs to the nuclear fatty acid receptor family (1, 2). In humans, four PPAR-γ isoforms have been identified: PPAR-γ1, PPAR-γ2, PPAR-γ3, and PPAR-γ4, with PPAR-γ1, 3, and 4 encoding the same protein; nevertheless, PPAR-γ2 is exclusively expressed in adipose tissue (3). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ plays a crucial role in various physiological functions, including glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and protection against oxidative stress. Disruptions in these metabolic pathways can lead to conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Several drugs that activate PPAR-γ have already received approval for sale, and their cardio-protective effects have been extensively investigated, making them potential therapeutic targets for CVDs (2, 4, 5). Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), such as rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, are specific PPAR-γ ligands that act as insulin sensitizers and are currently used to treat hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (6, 7). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is reported to have a relatively high expression level in vascular smooth muscle cells (8). Due to its presence in atherosclerotic plaques, a direct link between PPAR-γ and atherosclerosis, the primary cause of coronary artery disease (CAD), has been proposed (9). With the increasing prevalence of risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, and the established connection between PPAR-γ and these risk factors, PPAR-γ is emerging as a critical factor.

Regular exercise training and physical activity (PA) are important modifiable lifestyle factors that can significantly reduce the risk of CVD-related events and death by improving CVD risk factors, such as lipid profiles, blood pressure, body weight, and diabetes (10-19). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ gene expression in human adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance and CVD risk markers. Insulin resistance is known to be caused by reduced fatty acid oxidation, particularly in skeletal muscle (20, 21). Increased PPAR-γ expression in muscle and adipose tissue in response to physical exercise might contribute to the beneficial effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity. Therefore, investigating the effect of different types of exercise training on PPAR-γ levels as a key candidate for treatment and improvement of CVD risk factors is an important area of interest.

Exercise can also help prevent muscle atrophy (22). Biking for 8 weeks has been shown to up-regulate PPAR-γ-controlled genes and induce beneficial effects in skeletal muscle in healthy individuals (23). It has been reported that exercise protects against angiotensin II-induced muscle atrophy by activating PPAR-γ and suppressing miR-29b (22). Available evidence suggests that standardized exercise bouts also increase PPAR-γ activity. This systematic review investigates, for the first time, the effect of different types of PA on PPAR-γ expression and activity, aiming to determine whether the type of PA or health condition can influence the effectiveness of PPAR-γ.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Search Strategy

The PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases were searched for relevant literature published between January 2000 and May 2022. The phrases “training", “physical activity", “exercise", AND “Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor gamma", “PPAR-γ", were searched for in the title, keywords, and abstract. Boolean operators 'AND' and 'OR' were used to connect the search terms. Keywords from separate categories were combined with “AND", whereas those from the same category were combined with “OR". Additionally, the literature and references listed in relevant reviews were checked. In the search, subject headers and unrestricted text were integrated, and the search algorithm was modified in accordance with the characteristics of the various databases. The search strategy in PubMed as an example has been mentioned here: (((Training [Title/Abstract]) OR (physical activity [Title/Abstract])) OR (exercise [Title/Abstract])) AND (Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor gamma (PPAR-γ [Title/Abstract]))).

2.2. Study Selection

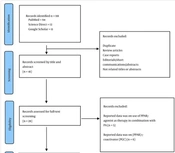

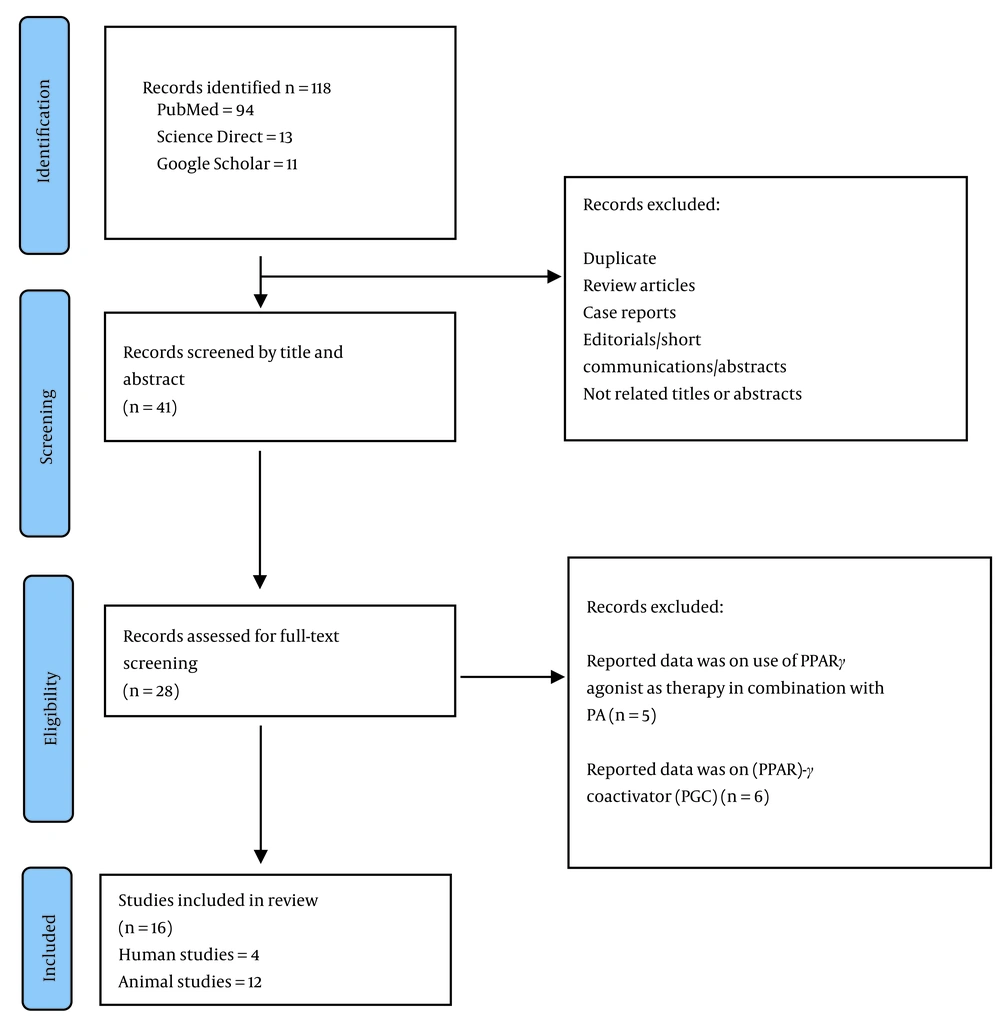

The study selection process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (24). Selected articles were imported into the EndNote Reference Manager (version 8.1), and both automated and manual procedures were used to remove duplicates. Two independent reviewers initially assessed the papers based on their titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text screening in accordance with the qualifying criteria. Any disagreements during the study selection process were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

For inclusion in this review, studies (cohort, clinical trials, and experimental) had to meet the following criteria: Studies that were written in English, included subjects (both humans and animals) who underwent PA and exercise training programs, and assessed PPAR-γ levels after the intervention. This review excluded case reports, editorials, case series, and review articles.

2.4. Study Selection

The full text of the included studies was carefully reviewed, and information was extracted, including the first author’s name, publication date, study design, details of PA and training programs, reported outcomes regarding PPAR-γ changes, and any other relevant information.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

The initial database search yielded a total of 118 articles. Figure 1 illustrates the detailed study selection process. In summary, after screening the titles and abstracts, 41 of the retrieved articles underwent full-text screening. Ultimately, 16 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review, with 4 involving humans (23, 25-27) and the remainder involving animals. Given the limited number of human studies on this topic and the desire for a comprehensive review, the current review included all studies, regardless of their quality. Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of the included studies and the extracted data.

| Authors/Year | Country | Design | Population | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoseini et al. 2022 (26) | Iran | Single-blinded, controlled RCT | Human/T2DM (48 males) (aged 35 - 50 years) | AE for 20-40 min/day, 3 days per week for 8 weeks | A significant increase of PPAR-γ mRNA expression level after exercise |

| Fatone et al. 2010 (27) | Italy | Comparative study | Human/T2DM; 8 subjects (2 females and 6 males), aged 38 to 74 years | 1-year exercise program consisting of 2 weekly sessions of 140 min that combined aerobic and resistance circuit training | A significant increase in PPAR-γ mRNA expression level after exercise (P = 0.024) |

| Tunstall et al. 2002 (25) | Australia | Clinical trial | Human/healthy (N =7) (3 males, 4 females, 28.9 ± 3.1 years | 9-day AE (60 min cycling per day) | PPAR-γ mRNA expression level was unaltered after AE and at 3 h post-AE |

| Thomas et al. 2012 (23) | UK | Cohort | Human/healthy individuals (n= 9, 32 ± 8 years) | 8-week exercise (45 min of cycling) | PPAR-γ mRNA expression levels were up-regulated |

Abbreviations: NR, not reported; RCT, randomized clinical trial; T2DM, Type 2 diabetes mellitus; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rats; AE, aerobic exercise; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid.

| Authors/Year | Country | Design | Population/sample size | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawamura et al. 2004 (28) | Japan | Experimental | SHR-high fructose-fed rats (n = 40); Experimental group (n = 20) Control group (n = 20) | AE for 20 m/min, 0% grade, 60 min/day, 5 days/week | Exercise significantly upregulated the PPAR-γ mRNA expression level in all tissues and skeletal muscles, which was attenuated by temocapril. |

| Kawanishi et al. 2018 (29) | Japan | Experimental | Male C57BL/6 mice; Normal diet (ND) and sedentary (n = 7), ND with exercise training (n = 5), high-fat, high-fructose water diet (HFF) and sedentary (n = 11), and HFF with exercise training (n = 11) | AE or running on a treadmill | Exercise downregulated PPAR-γ expression in the liver and macrophages. |

| Kushkestani et al. 2022 (30) | Iran | Experimental | Obese T2DM-induced rats (n = 12) | 6 weeks of high-intensity AE | A significant increase in PPAR-γ mRNA expression level (P = 0.007) |

| Liu et al. 2015 (31) | China | Experimental | Male C57BL/6 mice (n = 24) (n = 8 for each group) (diet + SED); (diet + EXE); (diet + EXE + a selective PPAR-γ antagonist) | 12 weeks of AE | Exercise significantly upregulated the PPAR-γ mRNA expression level in the colon. Exercise prevents colonic inflammation in HFD-induced obesity by up-regulating PPAR-γ activity. |

| Motta et al. 2016 (32) | Brazil | Experimental | Obese C57BL/6 mice | AE | Exercise significantly upregulated the PPAR-γ mRNA expression level in an HFD. |

| Shirvani et al. 2021 (33) | Iran | Experimental | High fructose-fed rats (n = 32) (n = 8 per group): control, swimming, high-fat diet (HFD), swimming with HFD | 8 weeks of swimming | Swimming significantly upregulated the PPAR-γ mRNA expression level in an HFD. |

| Chen et al. 2016 (34) | China | Experimental | 12-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (n = 60) | Treadmill running | Exercise is effective for restoring PPAR-γ to normal levels. |

| Stotzer et al. 2015 (35) | Brazil | Experimental | Ovariectomized rats (n = 30, (n = 6/group) sham-sedentary, ovariectomized-sedentary, sham-RT, ovariectomized-RT Resistance training (RT) | 10-week climbing training on a ladder with progressive overload | Climbing significantly upregulated the PPAR-γ mRNA expression level. |

| Szostak et al. 2016 (36) | France | Experimental | Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice | 3-month endurance swimming (5 days/weeks) in water at 35-36°C | Atherosclerotic lesion size was significantly reduced in the trained group compared to sedentary ones. Swimming significantly increased PPAR-γ expression in the aorta. The PPAR-γ expression was inversely correlated with the atherosclerotic plaque area. |

| Zheng, F., Cai, Y. 2019 (37) | China | Experimental | HFD mice (n = 20) healthy mice (n = 10) | 12 weeks of swimming | An increased expression of PPAR-γ protein after swimming |

| Amerian et al. 2021 (38) | Iran | Experimental | Male Wistar rats fed with deep frying oil (DFO) (n = 30) Healthy control (n = 6), DFO (n = 6), aerobic training + DFO (n = 6), octopamine + DFO (n = 6) and aerobic training + octopamine + DFO (n = 6) | AE for 4 weeks, 5 sessions per week | AE caused a significant decrease in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a significant increase in PPAR-γ gene expression. |

| Yazdanpazhooh et al. 2019 (39) | Iran | Comparative experimental study | T2DM induced rats (n = 14) exercise (n = 7) and control (n=7) groups | 6 weeks RT, including climbing on a stepladder (5 days/weeks) | Resistance training significantly increased PPAR-γ compared to control (P = 0.013). |

Abbreviations: NR, not reported; RCT, randomized clinical trial; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; SED, sedentary; EXE, voluntary exercise; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rats; AE, aerobic exercise; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; HFD, high-fat diet; RT, resistance training.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we investigated the association between physical exercise and PPAR-γ. The investigated 4 human studies included 1 randomized clinical trial (RCT), 1 experimental study, 1 cohort study, and 1 clinical trial. Each of these studies had a different study design. Due to the diverse nature of the studies, including human and animal research and observational and randomized trials, conducting a meta-analysis on this topic was not feasible. Therefore, a systematic review approach was adopted to collect and analyze the available literature, ensuring a comprehensive and unbiased examination of the existing research.

The current results from the 4 human studies indicated that in 75% of cases, moderate-term aerobic exercise (AE) and long-term AE significantly increased PPAR-γ mRNA expression levels (23, 26). However, one human study demonstrated that short-term AE (9 days) had no impact on PPAR-γ mRNA expression levels (25). Furthermore, the results of human studies revealed that AE significantly improved PPAR-γ levels in both individuals with T2DM and healthy subjects.

Among the 12 included animal studies, 11 papers (91%) demonstrated that various types of exercise and training programs, such as regular exercise, resistance exercise, swimming, climbing, and treadmill running, effectively improved PPAR-γ levels (28, 30-39). Only one study by Kawanishi et al. reported that AE downregulated PPAR-γ expression in the liver and macrophages (29). Both human and animal studies consistently showed that AE improved PPAR-γ mRNA or protein levels, consistent with previous reports that AE, regardless of type or duration, might up-regulate PPAR-γ mRNA expression in fat deposits (40-43).

Additionally, the present review included the study by Hoseini et al., which was the only human randomized controlled trial (RCT) in this review (26). In their study, 48 T2DM males were randomly assigned to one of four groups, each consisting of 10 subjects: exercise plus vitamin D, exercise, vitamin D, and control. Their findings after 8 weeks indicated that all groups, except the control group, experienced significant increases in antioxidant capacity (TAC), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT), in addition to significant decreases in insulin resistance (homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance [HOMA-IR]) and fasting blood glucose (FBG). Eight weeks of exercise also increased gene expression of PPAR-γ in T2DM patients, compared to the control group (26). Another study conducted by Fatone et al., involving 8 patients with T2DM who underwent 1-year combined AE and resistance training, revealed a significant increase in PPAR-γ and PPARα mRNA levels after 6 months of intervention, along with a significant reduction in FBG and HOMA-IR (27).

In a cohort study involving healthy individuals participating in an 8-week AE program, samples were collected before (pre) and after (post) standardized submaximal activity bouts (45 minutes of cycling at 70% of maximum O2 uptake, calculated at baseline) at weeks 0, 4, and 8. Plasma samples were added to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ response element (PPRE)-luciferase reporter gene assays, revealing higher PPAR-γ activity after standardized exercise bouts, indicating the generation of PPAR-γ ligands during exercise. However, during the training program, increases in PPAR-γ/PPRE-luciferase activity in response to the same standardized exercise bout were blunted, suggesting that the relative exercise intensity might affect PPAR-γ ligand generation (23). It has also been suggested that exercise-induced benefits might extend to monocytes, as monocyte PPAR-γ activation has been linked to beneficial anti-diabetic effects. Therefore, exercise-induced monocyte PPAR-γ activation might provide another reason to recommend exercise for patients with T2DM (23).

However, only one study showed that exercise training reduced the amount of macrophages in the liver and down-regulated PPAR-γ mRNA gene expression levels in the liver and macrophages in a non-alcoholic steatohepatitis model in mice (29). The remaining animal experiments confirmed an increase in PPAR-γ mRNA (28, 30-36, 38) and PPAR-γ protein (37, 39) levels after exercise. A study on obese diabetic rats subjected to high-intensity interval training and a control group (5 sessions of 30 minutes per week) showed that the expression level of PPAR-γ 48 hours after the last training session was significantly increased (30). Motta et al. also reported that high-intensity interval training led to significant reductions in body mass index (BMI) and FBG, improvements in the lipid profile, and an increase in PPAR-γ levels (32).

In an experimental study by Amerian et al., 30 adult rats were fed deep-frying oil and then underwent exercise training. Amerian et al. observed that deep-frying oil consumption significantly increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and significantly reduced PPAR-γ gene expression levels. Reactive oxygen species generated during the cooking process lead to oxidative stress, and because these products are absorbed by food and reach the circulatory system after consumption, they impact mitochondrial activity. An increase in ROS inhibits the ability of PPAR-γ to express and differentiate adipocytes, leading to a decrease in PPAR-γ gene expression. On the other hand, the duration and intensity of AE might have been such that, through brown adipose tissue adaptation and activation of antioxidant pathway factors, antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase, are increased, subsequently reducing oxidative stress caused by deeply heated oil in the mitochondria and further increasing PPAR-γ gene expression (38). Liu et al. also observed that exercise elevated PPAR-γ gene expression levels and activity in the colons of both high-fat diet and normal animals (31).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is the most extensively researched among the three PPAR subtypes. Due to alternative splicing and various promoters, PPAR-γ has two distinct isoforms, namely PPAR-γ1 and PPAR-γ2, with the latter containing 30 additional amino acids at the N-terminus (44). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ controls hundreds of genes, many of which are involved in energy, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism. Additionally, PPAR-γ acts as a modulator of inflammation and fluid homeostasis. It is considered a master regulator of adipogenesis, being necessary and sufficient for the formation of adipocytes (45, 46). Treatment with PPAR-γ ligands inhibits inflammatory mediators (47). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) has been identified as a transcriptional co-activator of PPARs and is believed to be a key regulator of phenotypic adaptation induced by exercise (48).

Even in the absence of CAD, individuals with T2DM exhibit increased insulin resistance and decreased exercise capacity compared to equally active, age-matched, and body-matched healthy individuals. Additionally, these patients often have excess fat mass, along with reduced exercise capacity. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, glycemic control, and lipid profiles while also affecting other CVD indicators (49-52), ultimately leading to improved exercise capacity (53, 54).

Yokota et al. demonstrated that the benefits of PPAR-γ agonists on exercise capacity in individuals with metabolic syndrome might be attributed, at least in part, to improved skeletal muscle energy metabolism, particularly fatty acid metabolism and mitochondrial function (55). However, Bastien et al. observed that in individuals with T2DM and CVD, treatment with the insulin sensitizer PPAR-γ agonist was associated with a worsening of AE capacity. This effect was primarily due to weight gain and expansion of subcutaneous fat mass despite improvements in insulin sensitivity, glycemic control, and metabolic conditions in these patients (56).

4.1. Limitations

This study has several significant limitations, including a limited number of human randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the inability to conduct a meta-analysis due to the high degree of heterogeneity among the studies, which encompassed various study types, including human, animal, observational, and randomized studies. The aforementioned factors increase the risk of bias.

4.2. Conclusions

The data collected in this systematic review suggests that all forms of AE, regardless of type and duration, might up-regulate PPAR-γ mRNA expression in fat deposits in both healthy subjects and those with T2DM.