1. Background

Considering the inevitable nature of earthquakes, preparedness should be taken into consideration. No one can either prevent or accurately predict such disasters in order to increase preparedness for the consequences. Besides direct damages, disasters may have various consequences due to lack of preparation, especially in developing countries.

Catastrophic events have been etiologically linked to a specific syndrome, known as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The question is how to prevent the adverse consequences, especially mental side effects, caused by such unpredictable disasters. The majority of studies on PTSD have been performed on adult exposure to extremely life-threatening situations, while there have been few empirical studies on children exposed to such situations (1). Overall, the highest prevalence of PTSD symptoms has been reported in children within 1 (2) to 5 years after the disaster (3).

PTSD symptoms tend to persist longer than those of depression (4). Therefore, it is necessary for PSTD patients, especially young women, to receive continuous psychological support (5). Overall, factors of age and gender have significant effects on PTSD symptoms after any type of treatment (6). Many studies suggest that people may overcome acute stress symptoms (ASSs) after periodic scheduled supportive counseling for at least 6 months (7). Many researchers have attempted to show that early trauma-focused, supportive psychological therapies are required for help-seekers after adverse events, such as natural disasters (8, 9).

Early interventions can particularly improve confronting abilities in those affected by chronic PTSD symptoms after an earthquake (10). There is adequate evidence to confirm the necessity of such therapies in preventing the damages of adverse events after PTSD symptoms are observed in a postcatastrophic period (11). Similar studies applying mental support showed very successful results in decreasing postshock symptoms of PTSD, especially among children (12).

On April 25, 2015 (local time, 11:56 a.m.), an earthquake with a massive surface-wave magnitude of 7.8 (Richter), followed by dozens of aftershocks, struck Nepal during the Asian football confederation (AFC) U-14 girls’ regional championship (13). The Iranian national team had also participated in the 20th AFC U-14 girls’ regional championship. In general, mass casualties during sport events are considerable, but earthquakes do not frequently occur during important international events.

The Nepal earthquake could have imposed PTSD on young members of the Iranian girls’ football team. The team physician considered the risk of PTSD among the players. Considering the far distance between the patient and physician for personal consultations, besides the long distance among patients for group activities, a web-based method (ie, sessions with an online application such as WhatsApp, as used in this study) was the only possible intervention.

The effects of web-based interventions on PTSD symptoms have been studied before, suggesting the feasibility of their application and prevention of persistent acute stress disorder (ASD) (14, 15). No similar studies have been carried out so far, as no similar events have occurred. An almost similar study was performed on 104 athletes, aged 12 - 18 years, who were training for the Pan American and olympic games in Haiti at the national sports center 1 year after the earthquake of Haiti (magnitude, 7.0) on January 12, 2010 (16). Nonetheless, this study focused on the physical damages of this event, not PTSD symptoms.

According to previous studies, catastrophic events etiologically lead to PTSD symptoms (1, 2, 4-6, 8, 10-12, 16-19). This disorder is highly treatable by supportive psychotherapy activities. In this paper, we studied the effects of online supportive psychotherapy on PTSD symptoms among the members of the Iranian U-14 girls’ football team following the Nepal earthquake.

2. Methods

The literature was searched to present a suitable treatment method for the most probable mental damages in players after a terrifying experience during an important travel. Scheduled online sessions, including group discussions, one-on-one consultation via WhatsApp, and periodic administration of questionnaires via phone calls were some of our continuous monitoring activities, based on our speculations. The search involved uncontrolled before-and-after case series.

2.1. Study Population

The study population consisted of 18 girls (age range, 12 - 13 years; mean, 12.61 ± 0.49 years), who were all members of the Iranian girls’ football team attending Nepal international competitions in 2015 while an earthquake occurred. One of the parents of each player was also enrolled in this study. Each member was from a distinct city in Iran. Although some members were from underprivileged villages, they were provided access to cell phones and the Internet. There was no control group in this study.

2.2. Questionnaires

The child report of posttraumatic symptoms (CROPS) is a 26-item self-report measure (5 minutes to complete, 1 minute to score), evaluating thoughts and feelings (internal) of 7- to 17-year-old children and adolescents. It covers a broad range of PTSD symptoms, with a cutoff score of 19, based on a meta-analysis of child trauma literature and diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) PTSD criteria. Although this scale has no parallel forms, the parent report of posttraumatic symptoms (PROPS) is usually used concomitantly to record the observable behaviours (external) of the target population.

A valid Persian-translated version of CROPS was ordered online and used to assess the level of PTSD symptoms in the population. Greenwald and Rubin have provided preliminary support to confirm the validity and reliability of CROPS and PROPS for PTSD risk analysis (20). This study could also substantiate the available evidence for validating the Persian version of the questionnaire by implementing a method described in the literature (20) during a 1-year examination on a rare real-life disaster.

2.3. Procedure

Supportive psychotherapy was applied for the national U-14 girls’ football team since 2 weeks after the earthquake for 1 year by one of the authors. The process was clearly explained to the subjects and their parents, and verbal informed consents were obtained from the parents. We asked them to use WhatsApp social messenger on their cell phones (or their parents') to be monitored continuously. We did not have any access to the subjects afterwards, as they had to attend school in their cities. Therefore, they attended group and individual online meetings continuously, using the application for psychotherapy follow-ups.

During the first 2 months, online group meetings were held for 1 hour almost every day when the children returned home from school in the evening. The children talked about their experiences during the day or the night before. One-on-one consulting sessions were also held whenever signs and symptoms, such as stress, fear, depression, panic, anxiety, antisocial behaviours, nightmares, insomnia, and peer-struggle, were observed.

Some extra sessions were also planned for those who requested one-on-one meetings and consultations for themselves or their parents. This method was applied weekly for 6 months and then monthly for the next 6 months. Supportive psychotherapy, including group and individual consultation or conversation sessions, was performed continuously to ensure that no small symptom of mental disorder is ignored. The subjects were asked to describe their detailed behaviors towards people, including family members, classmates, relatives, or even strangers.

CROPS was administered once at baseline (2 weeks after the disaster) and once after 2 weeks (1 month after the disaster) for comparison with time-based targets, confirmed in the literature (eg, ASD threshold). The 26-item CROPS and 32-item PROPS were both used in conjunction. CROPS was administered 4 times (after 2 weeks, after 1 month, after 6 months, and after 1 year), while PROPS was completed 3 times with the first, third, and fourth CROPS tests. The probability of ASD was tested both internally (CROPS) and externally (PROPS).

2.4. Data Analysis

The measured indices were compared to the ASD threshold (cutoff score of 19 to indicate if one requires clinical support) every time the CROPS test was performed. Moreover, daily oral diaries of children were monitored to find any signs of disorders, including stress, fear, depression, panic, anxiety, antisocial behaviours, nightmares, insomnia, and peer-struggle. Statistical analysis was performed, using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM).

3. Results

The first administration of CROPS (2 weeks after the disaster) showed various PTSD symptoms in most cases, 14 of which were above the ASD threshold. The results of the first analysis are presented in Table 1. Table 1 shows high CROPS scores at the beginning of the study. Overall, 10 children had more than 19 indices, while 4 were on the border (exactly 19 indices). The maximum score was 25 (out of a total score of 26), which indicates a very high level of PTSD.

In-person psychotherapy has shown effectiveness in the prevention or early elimination of PTSD. Long-distance online supportive psychotherapy helped the subjects feel better, as lower scores were reported in girls with ≥ 19 indices only after 1 month of therapy. This status remained stable within 1 year after the disaster (Table 1); even maximum scores on the following tests did not present any risk of ASD.

| Index | Two Weeks | One Month | Six Months | One Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 20.06 | 6.00 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| Std | 2.48 | 2.36 | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| Min | 14 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 25 | 10 | 4 | 4 |

| Med | 20 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Over 19 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exactly 19 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Meanwhile, PROPS was administered for the parents to monitor external symptoms, based on their behaviors. If any internal symptom from the CROPS was confirmed with its counterpart index of external symptoms from the PROPS, the patient was found susceptible to ASD or PTSD. The results of the second test administration are presented in Table 2.

| Index | Two Weeks | Six Months | One Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 14.11 | 2.56 | 2.56 |

| Std | 3.70 | 1.92 | 1.92 |

| Min | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 23 | 6 | 6 |

| Med | 14 | 3 | 3 |

Table 2 presents supportive evidence for the results indicated in Table 1. As online supportive psychotherapy was applied, the girls showed a lower risk of exposure to stress signs or PTSD symptoms. Tables 1 and 2 show that ASD symptoms were at first risky, while they gradually disappeared via supportive psychotherapy.

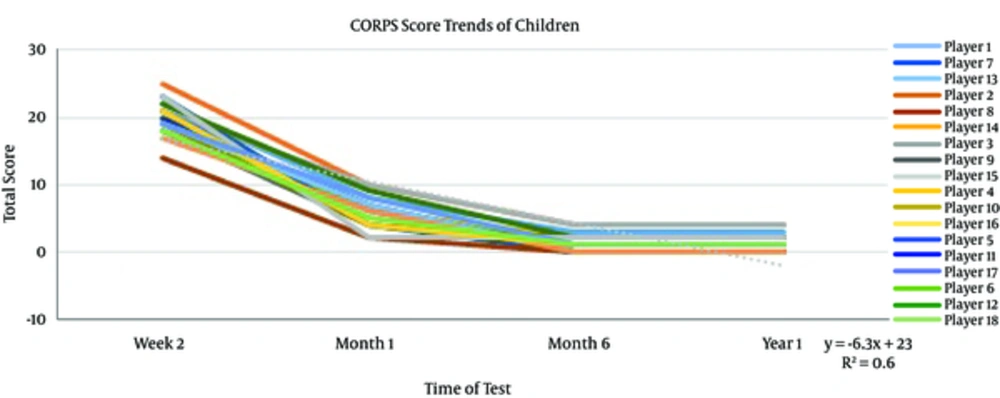

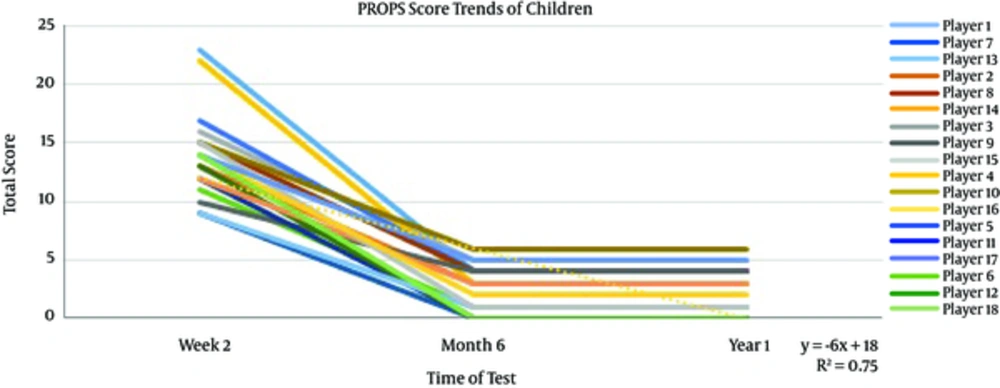

The descending trends of CROPS and PROPS scores (indicated by simple linear regression test with 95% confidence interval and Pearson’s R2 of 0.6 and 0.75, respectively) showed the positive influence of supportive psychotherapy, using web-based mobile applications when there is no direct access to the target population due to factors, such as lack of time, far distance, busy daily schedule, and high costs.

As the results were quite similar after 6 and 12 months, we conclude that all the children were satisfied after 1 year of monitoring. The comparison of Tables 1 and 2 shows that internal and external symptoms were both prevalent at first, while they decreased gradually due to online supportive psychotherapy (Figure 1).

As presented in Figure 1, the descending trend of children’s scores on CROPS during 1 year is a consequence of online supportive psychotherapy. In parallel with the internal symptoms of PTSD, the parents were tested via PROPS three times to record the external symptoms of potential PTSD. Figure 2 indicates these results in 3 test administrations.

Figure 2 confirms the validity of the results presented in Figure 1. The children seemed to show better behaviors (Figure 2) by receiving supportive psychotherapy, which was the direct consequence of their improved feelings (Figure 1). Table 3 reflects the total score of each question in every CROPS administration. As shown in Table 3, the total score of all questions is descending, which shows a suitable trend of mental health during online supportive psychotherapy.

| Question | W2 | M1 | M6 | Y1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q01 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q02 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Q03 | 19 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Q04 | 33 | 11 | 4 | 4 |

| Q05 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q06 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q07 | 27 | 8 | 3 | 3 |

| Q08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q10 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Q11 | 28 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Q12 | 30 | 12 | 3 | 3 |

| Q13 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Q14 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Q15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q16 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Q17 | 33 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Q18 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Q19 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q20 | 25 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Q21 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Q22 | 18 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Q23 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q24 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Q25 | 29 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| Q26 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Over 9 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

4. Discussion

Sudden events, especially natural disasters, result in PTSD among survivors. This study showed the effects of web-based supportive psychotherapy on 18 girls under 14 years, who were members of the Iranian national football team, attending Nepal international competitions in April, 2015 while an earthquake of 7.8 occurred. The shock during such an important travel could have noncompensable effects on their mental health (6).

Early interventions can particularly ensure confronting abilities for those affected by chronic PTSD symptoms after an earthquake (10). It is also confirmed that psychotherapy produces more sustainable active conditions than pharmacotherapies and pharmaceutical prescriptions, such as lafaxine and nefazodone or sertraline and venlafaxine, which have major bias potentials in methodological aspects (21). Some studies have demonstrated that supportive psychotherapy should start preferably not more than 2 weeks after a catastrophe (18).

Mass casualties during sport events are tremendous. Nonetheless, earthquakes do not commonly happen during an important international event. Nepal earthquake in April, 2015 could have imposed PTSD on young members of the girls’ national football team. No similar studies have been performed in this area, as no similar events have occurred so far. An almost similar research studied the reproductive health of a group of women after treatment of PTSD, caused by an earthquake (magnitude, 7.6) on October 8, 2005 in North Western provinces of Pakistan with major casualties and serious injuries (19).

Considering the far distance between the patients and physician for personal consultations, besides the long distance among patients for group activities, a web-based approach was the only possible intervention. The preventive effect of a web-based intervention on PTSD symptoms has been studied before, showing the feasibility of treatment and prevention of persistent PTSD symptoms (14, 15). The children participated in an urgent service program in which they were provided with supportive psychotherapy through online group and individual sessions by the help of communicative applications, based on a scheduled plan. Any signs of mental disorders were soon identified and intervened to avoid wasting time, which could in turn cause an acute PTSD symptom (15).

The CROPS was applied 4 times on children (2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year after the disaster). The parents were also tested by PROPS, concomitant with the first, third, and fourth CROPS tests. The results of the first test showed no signs or symptoms of PTSD, while the majority of players (78%; 14 out of 18) surpassed the ASD threshold (cutoff score, 19); however, it was not acute, as the mean score was 20.06 (± 2.48). The median score (20 ≥ 19) showed a scarce risk for the team to face acute stress reactions. Nevertheless, the results of the following tests showed a descending trend in their symptoms. In addition, ASSs never progressed to ASD. These results were predictable, as the literature had indicated that girls and adolescents, aged 13-18 years, are more prone to PTSD (5).

Table 3 shows a serious concern about the risk of PTSD symptoms, as 15 questions (57.7%) were answered “yes” by the players on the first test. As the weight of all questions was the same, there could be a potential risk of PTSD in more than half of the team members, which could lead to major problems in their future sport life. However, the risk significantly disappeared in the following test, as only 4 out of 26 (15.3%) questions were answered “yes” by the girls. The decreasing trend continued, and no questions were answered “yes” in 6-month and 1-year tests, showing that supportive psychotherapy through online sessions had major effects on the mental health of children, as previously confirmed (6, 18).

As the web-based method was the only implemented approach in this study, we cannot justify the accuracy or optimality of the results. However, it is obvious that the outcomes were completely satisfying for both researchers and study population. In comparison to the literature, the purpose of this study was not necessarily to find a scientific method to treat PTSD, while the focus was on preventing any symptoms of mental disorders.

Previous studies have shown the significant impact of web-based interventions on posttraumatic symptoms among children and adolescents, as they can be provided with accessible, timely, and cost-effective psychotherapies (18, 19). In the present study, the internal symptoms were more prevalent than the external ones. Some children had occasional nightmares or were afraid of loud noises, and some experienced aggressive situations at school. Many had problems sleeping at night, and few showed aggressive attitudes towards their family members; these findings have been confirmed in the literature (16).

4.1. Conclusion

Having entered an era of widespread communication, Internet-based supportive psychotherapy can be highly effective in situations where we do not have adequate access to patients or high-risk populations. Similar disasters can happen in the future, and as this study suggests, online supportive psychotherapy should be integrated as an alternative method, considering its cost-effectiveness, timesaving design, and internal/external deterrents to consulting a psychologist or psychotherapist. In general, online supportive psychotherapy can be an alternative treatment method, as well.

4.2. Limitations

The present study did not include a control group to determine if the results are the actual consequences of online supportive psychotherapy. This study presents a unique situation in the literature, as there have been no other similar cases with a young group of sensitive people attending an important contest. Also, we could not test the method on a control group (adjusted for gender, age, type of trauma, occupation, and type of supportive psychotherapy), although it has been previously studied in different situations (3, 5, 8).

4.3. Implications

High-risk PTSD situations can be managed via online supportive psychotherapy, especially among children, based on the CORPS test. Other types of questionnaires are needed to survey similar cases.

4.4. Patient Perspective

I really liked the online group and daily individual sessions. Every day, at school, I looked forward to getting home on time to go online on my mom’s cell phone and visit my doctor and my teammates. Whenever I face an unpleasant situation, I am sure there is a solution to it.