1. Context

Proprioception is defined as the ability to perceive body position and movement in space through the integration of sensory signals from various mechanoreceptors (1, 2). It is well established that proprioception plays a crucial role in joint position awareness, balance control, and other motor functions (3-5). Previous research has demonstrated that proprioception also significantly influences athletic performance, making it a determinant of success in sports (6, 7). Proprioception supports the motor system by maintaining tendon tonicity (8) and enhances strength, accuracy, and movement control, which are vital in both sports and general movement (3).

In the existing literature, there is some debate regarding the effect of physical exercise on proprioception (3). Exercises such as core stabilization (9), strength training (10), tai chi (11, 12), isokinetic training (13, 14), sensorimotor exercises (15), neuromuscular training (16), vibration therapy (17), resistance training (18), combined training programs (19), and Pilates (20) have been reported to improve joint position discrimination. However, some studies have shown no significant effect of exercise on proprioception (21-23).

One specific category of exercise whose effect on proprioception has yet to be fully assessed is plyometric exercise. Plyometric exercises involve rapid stretching of a muscle and its connective tissue (eccentric activity), followed by a forceful concentric contraction (the stretch-shortening cycle) (24). These exercises are primarily used to enhance mechanical power during successive movements by relying on the elastic energy stored in the muscles and the stretch reflex (24, 25). Evidence suggests that plyometric training improves various physical attributes such as explosive power, jumping ability, sprinting speed, agility (26, 27), and endurance (28). Additionally, plyometric exercises are thought to benefit the musculoskeletal system by increasing bone mass, enhancing the stiffness of muscle-tendon complexes, and improving overall muscle function (28-30). Given these benefits, it is plausible to hypothesize that plyometric exercises may also improve proprioception.

To test this hypothesis, it is necessary to conduct experiments under various conditions, as there are multiple variants of plyometric exercises and approaches for assessing proprioception. Any study that attempts to establish a causal relationship between plyometric training and proprioception would be limited to the specific experimental protocol employed.

2. Objectives

To provide more general insights, this systematic review aims to assess the influence of plyometric exercises on proprioception, either directly or indirectly, by reviewing the relevant literature.

3. Methods

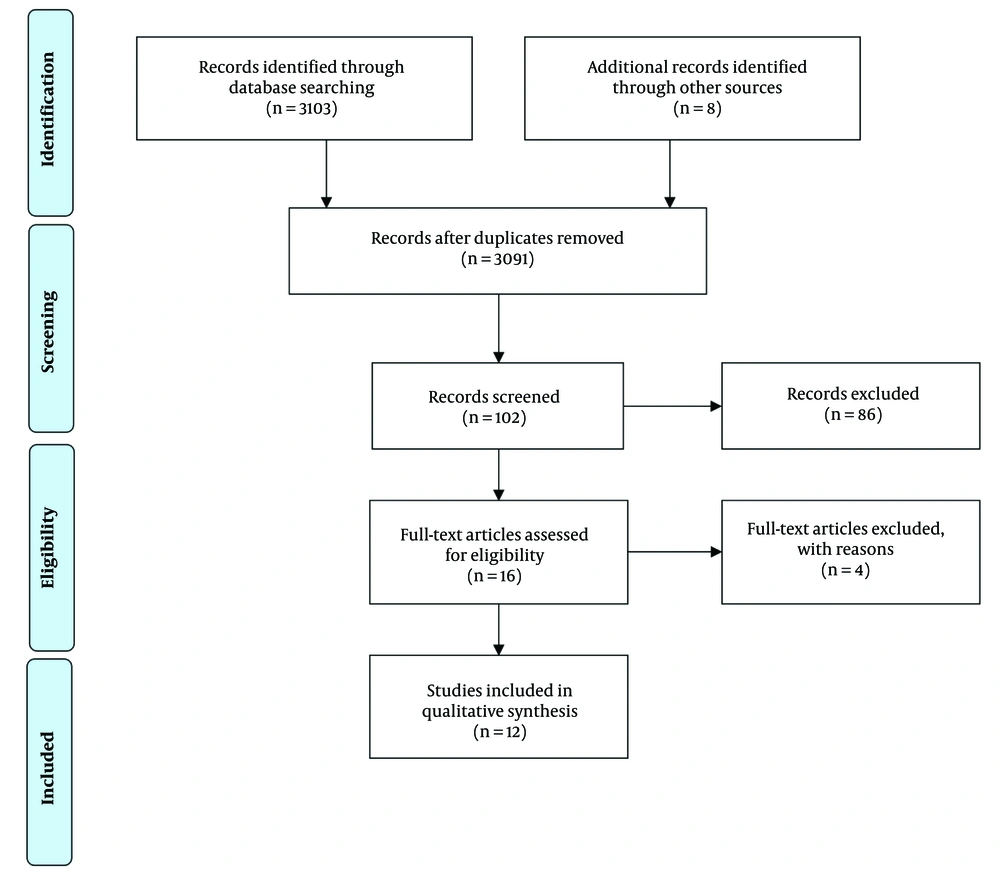

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (31) (Figure 1). The review also adhered to the PICO (Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design) framework for assessing the effect of plyometric training on proprioception (32). The study has been registered with the international online registry PROSPERO under the code CRD42024563346.

3.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive digital search was conducted in October 2022 across multiple databases, including PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Science Direct, Google Scholar, DOAJ, IEEE Xplore, and Cochrane. The search covered studies from 1990 to October 2022, and terms based on Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used. These search terms included “proprioception,” “kinanesthesia,” “kinesthesia,” “kinesthetic sense,” “sense of self-movement,” “body position,” “sixth sense,” “position movement sensation,” “sense of locomotion,” “limb position,” “joint position,” “muscle sense,” “proprioceptive,” “proprioceptors,” “joint afferent,” “mechanosensation,” “mechanosensitive,” “muscle sensation,” “muscle sensibility,” “muscle sense,” “muscular sensibility,” “myaesthesia,” “myesthesia,” “sense of equilibrium,” “sense of balance,” “interception,” “vestibular,” “myoaesthesia,” “myoesthesia,” “plyometric,” “jump training,” “plyos,” “shock method,” “jump exercise,” “jump workout,” “Stretch-Shortening Cycle,” and “Ballistic resistance training.”

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this systematic review, articles had to meet the following inclusion criteria: They had to be randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have full-text articles available in English, use valid and reliable assessment tools, and report the effects of plyometric training on proprioception. The exclusion criteria included studies that were not in English, as well as book chapters, conference papers, conference posters, and dissertations.

3.3. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

No restrictions were placed on age, gender, participants, or statistical methods due to the limited number of studies available for review. Instead, the review focused on identifying the effects of plyometric exercises on proprioception. If disagreements between reviewers arose, they discussed the relevant abstracts to reach a consensus, and a third reviewer was consulted if necessary. After this process, 12 articles were selected for inclusion in the final review.

The quality of each study's methodology was assessed using a modified 27-item version of the Downs and Black Checklist (33). Items were scored as either yes = (1), no or unable to determine = (0), except for item 5, where yes = (2), partially = (1), and no = (0). The maximum possible score for each study was 28. Based on their scores, studies were classified into quality levels: Excellent (26 - 28), good (20 - 25), fair (15 - 19), and poor (≤ 14) (33). The risk of bias was independently evaluated by two reviewers, focusing on six key areas: (1) bias in selecting participants, (2) bias in classifying interventions, (3) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (4) bias from missing data, (5) bias in measuring outcomes, and (6) bias in selective reporting of outcomes. Studies with a high risk of bias across all categories were excluded from the review (34).

4. Results

A total of 386 participants, both control and intervention groups, were included across the 12 studies assessed. Nine of these studies involved healthy individuals, while three focused on people with specific conditions: (1) multiple sclerosis (MS) (35), (2) functional ankle instability (FAI) (36), and (3) those with grade I or II unilateral inversion ankle sprain (37).

The length of interventions varied, ranging from eight days to 12 weeks, with six weeks being the most common. Most interventions were conducted with a frequency of two to three sessions per week, with three sessions being the most common. Plyometric exercises across studies included jump training, throwing, hops, dynamic lunges, and exercises like kick butt.

According to the data presented in Table 1, ten studies reported positive effects of plyometric exercises on proprioception (35-44), while two studies found no significant effects (45, 46).

| Study | Participants | Intervention | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Characteristics | Plyometric Intervention | Frequency | Duration | Control | ||

| Zhou et al., (2022) (38) | 16 | Healthy elite male badminton players | Combined training: 40 minutes of plyometric training and then 20 min of balance training on an unstable support (e.g., BOSU ball, Swiss ball, and Balance pad). | 1 hour, 3 sessions Per weeks | 6 weeks | Plyometric training: Participants completed 40 min of plyometric training (e.g., depth jump and lateral barrier jump) and then 20 min of balance training on a stable support. | Both groups led to significant improvements in proprioception |

| 24 | Female division I swimmers | Regular swimming training program with additional plyometric training, focused on strengthening the internal rotators of the shoulder (exercises with elastic tubing and the Pitchback System) | Three sets of 15 repetitions were performed 2 days a week | 6 weeks | Regular swimming training program | Plyometric training resulted in significant improvement in proprioception kinesthesia. The plyometric group improved significantly more than the control group in 5 out of 6 proprioceptive tests (active reproduction of passive positioning) | |

| Swanik et al., (2002) (39) | 22 | Healthy be- ginner female badminton players, | Plyometric training which consisted of jumping exercises (e.g., wall jumps, squat jumps, board jumps, box jumps, etc.), performed in three levels of difficulty | 20 minutes with 10 minutes Warm up and cool down, three times per week | 6 weeks | Continued their usual badminton training and practice, | The knee joint angle reconstruction absolute error significantly improved in the intervention group compared to controls after plyometric training |

| 25 | Female experienced-volleyball players for at least 2 years | Group I received a technical volleyball training program with a weighted rope. Group II was given the same training program but with a normal rope. | 3 sessions a week | 12 weeks | Followed only a technical volleyball training program for the same duration, | Proprioception improved in both intervention groups, no significant difference was found between the weighted rope jump groups and controls. | |

| Alikhani et al., (2019) (40) | 20 | Female volunteers with relapsing remitting MS | Neuromuscular exercises, and in the last 2 weeks, plyometric exercises (Dynamic lunge, Side step up, Vertical jump, Pair jump, Hopping) were added with different intensities | 60 min (10 min warm up, 45 exercise, 5 min cool down), 3 sessions a week | 8 weeks | They were asked to maintain normal daily activities during the 8‐week intervention. | The proprioceptive error during evaluating angular reconstruction decreased significantly in the experimental group, but not in the control group. |

| 10 | Male collegiate soccer players | Plyometric training (Squat Jump, Tuck jump, Box Jump Up, Box Jump Down, Horizontal Jump, Butt Kick) | Training Intensity was increased | 6 weeks | Postural stability training | Plyometric training significantly improved proprioception and postural stability (P < 0.05) | |

| Ozer et al., (2011) (45) | 44 | Male subjects playing in three teams in the Victorian Football League (VFL) | Normal football training plus jump-landing | 10 minutes, 3 sessions | 8 weeks | Normal training | Knee and Ankle discrimination improved overall pre to post test in normal training plus jump-landing group compared to normal training group. |

| 78 | Sedentary, college-aged females | Plyometric training, (On the Plyoback System and fom the center of the trampoline, throwing the weighted balls at it using a one- handed overhead throw of the dominant arm) | 2 sessions per week | 8 weeks | Control group | None of plyometric training group and control group exhibited a significant change in kinesthetic score | |

| Sokhangu et al., (2022) (35) | 75 | Swimmer boys | Study group (1) received plyometric training for the rotator cuff muscles | 2 sessions per week | 8 weeks | Control group (2) had no strength training, Study group (3) received isokinetic training, -Three groups swam for four hours per week in the eight weeks through- out the study. | Plyometric group showed significant differences in all measured variables with no significant changes being observed in the control group. |

| 22 | Athletes with grade I or II unilateral inversion ankle sprain | Plyometric Training (Side to side ankle hops, standing jump and reach, Front cone hops, Standing long jump, Lateral jump over barrier, Cone hops with 180 Degree turn, Hexagon drill, etc.) | 2 sessions per week | 6 weeks | Resistance Training | Both plyometric and resistive training improved isokinetic evertor and invertor peak torques and functional performance of athletes P < 0.05. There were no significant differences between groups concerning peak torque/body weight for investors and evertors at both speeds measured P > 0.05. The functional test measures of the plyometric group were significantly higher than that of resistance training group. | |

| Seo et al., (2010) (41) | 20 | Adults with FAI | Stable supporting surface jump group | 30 minutes, 3 sessions | 8 weeks | Unstable supporting jump group | In comparison between the groups, a significant difference in the plantar flexion range of the joint position sense after exercise was observed. |

| 30 | Male semi- professional fast bowlers | Ballistic six plyometric training with conventional upper extremity workouts | 60 minutes, 3 sessions | Weeks | Kinesio-taping along with ballistic six plyometric training with conventional upper extremity workouts | Ballistic six plyometric training group showed significant difference for Joint proprioception in comparison to control group. | |

| Waddington et al., (2000) (42) | Participants | Intervention | Outcome | ||||

| n | Characteristics | Plyometric Intervention | Frequency | Duration | control | ||

| Heiderscheit et al., (1996) (46) | 16 | Healthy elite male badminton players | Combined training: 40 minutes of plyometric training and then 20 min of balance training on an unstable support (e.g., BOSU ball, Swiss ball, and Balance pad). | 1 hour, 3 sessions per weeks | 6 weeks | Plyometric training: Participants completed 40 min of plyometric training (e.g., depth jump and lateral barrier jump) and then 20 min of balance training on a stable support. | Both groups led to significant improvements in proprioception |

| 24 | Female division I swimmers | Regular swimming training program with additional plyometric training, focused on strengthening the internal rotators of the shoulder (exercises with elastic tubing and the Pitchback System) | Three sets of 15 repetitions were performed 2 days a week | 6 weeks | Regular swimming training program | Plyometric training resulted in significant improvement in proprioception kinesthesia. The plyometric group improved significantly more than the control group in 5 out of 6 proprioceptive tests (active reproduction of passive positioning) | |

| Shemy and Battecha, (2017) (43) | 22 | Healthy be- ginner female badminton players | Plyometric training which consisted of jumping exercises (e.g., wall jumps, squat jumps, board jumps, box jumps, etc.), performed in three levels of difficulty | 20 minutes with 10 minutes warm up and cool down, three times per week | 6 weeks | Continued their usual badminton training and practice, | The knee joint angle reconstruction absolute error significantly improved in the intervention group compared to controls after plyometric training |

| 25 | Female experienced-volleyball players for at least 2 years | Group I received a technical volleyball training program with a weighted rope. Group II was given the same training program but with a normal rope. | 3 sessions a week | 12 weeks | Followed only a technical volleyball training program for the same duration, | Proprioception improved in both intervention groups, no significant difference was found between the weighted rope jump groups and controls. | |

| Ismail et al., (2010) (37) | 20 | Female volunteers with relapsing remitting MS | Neuromuscular exercises, and in the last 2 weeks, plyometric exercises (Dynamic lunge, Side step up, Vertical jump, Pair jump, Hopping) were added with different intensities | 60 min (10 min warm up, 45 exercise, 5 min cool down), 3 sessions a week | 8 weeks | They were asked to maintain normal daily activities during the 8‐week intervention. | The proprioceptive error during evaluating angular reconstruction decreased significantly in the experimental group, but not in the control group. |

| 10 | Male collegiate soccer players | Plyometric training (Squat Jump, Tuck jump, Box Jump Up, Box Jump Down, Horizontal Jump, Butt Kick) | Training intensity was increased | 6 weeks | Postural stability training | Plyometric training significantly improved proprioception and postural stability(P < 0.05) | |

| Park and Kim, (2019) (36) | 44 | Male subjects playing in three teams in the Victorian Football League (VFL) | Normal football training plus jump-landing | 10 minutes, 3 sessions | 8 weeks | Normal training | Knee and Ankle discrimination improved overall pre to post test in normal training plus jump-landing group compared to normal training group. |

| 78 | Sedentary, college-aged females | Plyometric training, (On the Plyoback System and fom the center of the trampoline, throwing the weighted balls at it using a one- handed overhead throw of the dominant arm) | 2 sessions per week | 8 weeks | Control group, | None of plyometric training group and control group exhibited a significant change in kinesthetic score | |

| Saran et al., (2022) (44) | 75 | Swimmer boys, | Study group (1) received plyometric training for the rotator cuff muscles | 2 sessions Per week | 8 weeks | Control group (2) had no strength training, Study group (3) received isokinetic training, -Three groups swam for four hours per week in the eight weeks through- out the study. | Plyometric group showed significant differences in all measured variables with no significant changes being observed in the control group. |

Table 2 provides the results from the Downs and Black checklist, which was used to assess the quality of the included studies.

| Article | Reporting (n = 10) | External Validity (n = 3) | Internal Validity | Power (n = 1) | Total (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias (n = 7) | Confounding (n = 6) | |||||

| Zhou et al., (2022) (38) | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| Swanik et al., (2002) (39) | 7 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| Alikhani et al., (2019) (40) | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| Ozer et al., (2011) (45) | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 11 |

| Sokhangu et al., (2022) (35) | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 18 |

| Seo et al., (2010) (41) | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 16 |

| Waddington et al., (2000) (42) | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 13 |

| Heiderscheit et al., (1996) (46) | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| Shemy and Battecha, (2017) (43) | 8 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 22 |

| Ismail et al., (2010) (37) | 7 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 18 |

| Park and Kim, (2019) (36) | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 13 |

| Saran et al. (2022), (44) | 7 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

a Downs and Black score ranges: Excellent (26 - 28); good (20 - 25); fair (15 - 19); and poor (≤ 14) (33).

Significant effects of proprioception on both upper and lower limbs were reported across the studies assessed (Table 1). Three studies specifically explored the effects of plyometric training on upper extremity proprioception (46) and rotator cuffs (39, 43). The first study by Heiderscheit (1996) (46), which involved plyometric training using a one-handed overhead throw on a trampoline, did not show any significant change in kinesthetic scores. In contrast, the studies by Swanik et al. (2002) (39) and Shemy and Battecha (2017) (43) demonstrated that plyometric training significantly improved the proprioception of the rotator cuffs.

Two other studies (36, 38) focused on lower limbs and examined the effects of plyometric training using stable and unstable supporting surfaces. One study (38) found that combining plyometric and balance training on unstable surfaces increased proprioception in both dominant and non-dominant legs. Another study (36) showed that jump plyometric training yielded significant improvements only in plantar flexion range of motion (ROM) sense, specifically in the ankle joint position sense.

A study (45) on weighted and non-weighted rope exercises reported improvements in proprioception in both groups, although there was no significant difference between the proprioception scores of the weighted rope jump group and the control group.

Additionally, a combination of plyometric and neuromuscular training studied by Sokhangu et al. (2022) (35) indicated enhanced proprioception in the intervention group compared to the control group. Other studies (37, 40-42), which investigated the effects of plyometric training through jumping and hopping exercises or using ballistic six plyometric exercises (44), also reported significant increases in proprioception in the intervention groups.

Lower limb plyometric training mainly involved exercises such as squat jumps, tuck jumps, box jumps, side-to-side hops, and cone hops (35-38, 40-42), with one study (45) using only rope exercises. For upper limb training, a wider variety of exercises were used, including throwing (46), throwing and catching (39), and ballistic movements (43, 44).

Proprioception was assessed through various methods. Five studies (35, 37, 39, 41, 43) employed a Biodex isokinetic dynamometer device. Other studies used different tools, including the Charles Bell tool (45), the AMEDA device (42), and the LIDO Active Multi-Joint II Isokinetic system (46). Simpler methods, such as photography (39), electro-goniometer (36), inclinometer (44), and force plate (38), were also utilized.

Excluding the study by Heiderscheit et al. (1996) (46), which focused solely on throwing exercises for the upper limbs, and the study by Ismail et al. (2010) (37), which combined jump and hop exercises for the lower limbs, significant improvement in proprioception was observed in the remaining studies.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to systematically review the effects of plyometric exercises on proprioception. Based on the 12 studies included in this review, it was observed that various types of plyometric training and different methods of proprioception assessment were considered. Overall, the results suggest that plyometric training has a generally positive effect on proprioception, regardless of the specific training protocol or assessment metric used.

In most of the studies involving lower limb plyometric exercises (35-38, 40-42), the exercises included different types of jumping and hopping, such as squat jumps, tuck jumps, box jumps, side-to-side hops, and cone hops. Only one study (45) focused on rope exercises. While all studies reported significant effects of plyometric exercises on proprioception, some did not pass the full requirements of the Downs and Black checklist for study quality. Notably, four of the eight studies on lower limb plyometric exercises (36, 38, 42, 45) did not fully describe their outcome measurements, which is critical for determining the quality of the findings. In contrast, four studies (35, 37, 40, 41) used isokinetic machines for proprioception assessment, with three reporting positive effects of plyometric training on proprioception.

Regarding study reliability, the majority of the lower limb studies had consistent intervention parameters and participant numbers. The most common duration for interventions was six weeks, and the average number of participants was 19.28, with one study involving 44 subjects. Most studies scored well in the external and internal validity sections of the checklist, although some unknown or non-reported details about randomized intervention assignments affected the internal validity scores in a few studies (38, 40-42, 45).

In terms of upper limb plyometric exercises, four studies were reviewed (39, 43, 44, 46). Three of these studies (39, 44, 46) received fair or poor quality scores based on the checklist, with only one study (43) achieving a good score. Despite variations in assessment methods and training tools, all four studies generally indicated positive effects of plyometric exercises on proprioception, involving a total of 207 subjects. Thus, it can be concluded that plyometric exercises improve proprioception for both upper and lower limbs, although there is variability in study quality.

5.1. Limitations

One of the main limitations of this review is the limited number of randomized controlled trials with control groups. Additionally, most of the reviewed studies had small sample sizes, and gender differences were not accounted for in most cases. Another limitation was the variety of plyometric exercises used across studies, which may have influenced the effect on proprioception. Furthermore, the use of different tools for assessing proprioception could have impacted the consistency and accuracy of the results.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the studies reviewed, it is evident that plyometric exercises likely enhance proprioception. Although there are variations in the types of plyometric training and assessment methods used, the overall findings support the potential of plyometric exercises to improve proprioception in both upper and lower limbs. Future research with larger sample sizes, more standardized assessment methods, and better study designs is recommended to further substantiate these findings.