1. Background

The running performance of middle- and long-distance runners is influenced by factors, such as maximal oxygen uptake (V̇O2Max), velocity at V̇O2Max (vV̇O2Max), maximum metabolic steady state (MMSS), running economy (RE), and sprint capacity (1). While performance adaptations depend on training characteristics, both high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and resistance training (RT) models offer viable alternatives for training periodization (2).

Training for endurance runners aims to improve both performance and its physiological determinants, which appear to influence performance in highly trained or elite runners competing in events ranging from 1500 m to the marathon (3). The training process emphasizes several key aspects, including periodization, training methods and monitoring, performance prediction, running technique, and the prevention and management of injuries related to endurance running (4).

Interval training involves alternating between short bursts of intense exercise and periods of lower-intensity activity or complete rest for recovery (5). High-intensity interval training is an extension of IT (6), enhancing an athlete's cardiorespiratory and metabolic functions, improving both aerobic and anaerobic capacities, and ultimately leading to better physical performance (7).

There is limited research on how coaches of well-trained middle- to long-distance runners apply IT methods. While research tends to emphasize physiological outcomes, coaches prioritize performance, creating a gap between the IT techniques studied in research and those used in practice (8).

Interval and combined training are more effective strategies than continuous training for improving athlete performance (9). In contrast, a framework for integrating strength training (ST) with traditional sport-specific training can enhance middle- and long-distance performance by reducing the energy cost of locomotion and increasing maximal power and strength (10).

Power training, which combines plyometric and resistance exercises, can benefit recreational, young male, and well-trained distance runners (11). This type of training can improve their explosive strength, neuromuscular function, RE, and endurance performance across various training intensity targets (12).

Plyometric training, an extension of power training, enhances pre-adolescent boys' muscle thickness, stride angle, fascicle length, tendon stiffness, jumping ability, lower body strength, and stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) (13). Heavy RT, compared to plyometric training, improves distance runners' knee and ankle strength, leg acceleration, propulsion, biomechanical and neuromuscular changes, RE, and TT performance (14).

Explosive plyometric and high-intensity RT, which combine concurrent strength and endurance training (SET), lack explicit discussion (15). The impact of ST on work economy, V̇O2Max/V̇O2peak, general strength, and running performance has typically been studied across a wide range of trained and well-trained individuals, including those of varying age, sex, experience, and disciplines, particularly in middle- and long-distance runners (16).

The effects of ST on physical, physiological, and training-related factors, especially in 800 m to 1500 m runners, have been explicitly examined in previous studies (16-20). However, the combined effects of interval and power training on participants of different ages, genders, training backgrounds, events, and control conditions, particularly in middle- and long-distance running ranging from 800 m to 10000 m, remain unclear (21-24).

The combined effects of interval and power training interventions, compared to a control group, do not consistently show superior improvements in all physical, physiological, and training characteristics.

1.1. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

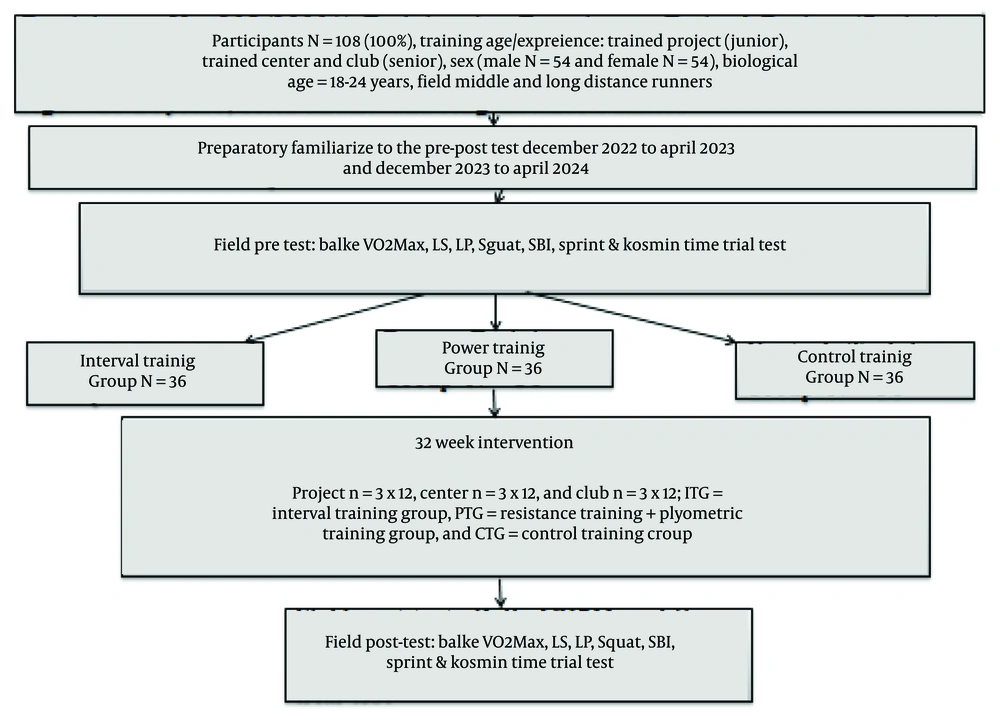

The experimental design shown in Figure 1 was adapted from a previous source (1, 24) and has been modified.

2. Objectives

One of the objectives of this study was to investigate the combined effects of customized interval and power training interventions compared to a control group over an extended period.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area, Population, and Sample Size Determination

This research was conducted in Debre Berhan City, located in the central highlands of the North Shewa Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. The study involved a total population of 108 athletes, representing 100% of the target group. To determine the appropriate sample size, the researchers used the Yamane Taro formula:

Where, n is the sample size, N is the total population, and e is the margin of error. This formula ensures that the sample size is adequate for drawing reliable conclusions about the overall population.

Participants were recruited from three sources: The Athletics Club of Debre Berhan University, the Athletics Training Centre of Debre Berhan City, and the Cha-cha Town Athletics Project. This census sampling approach provided a comprehensive dataset, enabling a thorough analysis of the training interventions' effects on athlete performance (25, 26).

3.2. Research Design

The study was conducted in the specified geographical area. The total population was determined, and the sample size was calculated for each of the three groups: IT, power training, and control group. A total of 12 athletes were randomly assigned to each of these three training groups using a randomized block design (26, 27).

3.3. Informed Consent

Participants were informed about their involvement in the study verbally, rather than in writing. As such, informed consent was obtained through the participants' demonstration of full willingness to participate. Furthermore, participants were assured that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they experienced any inconvenience, with the intent to ensure there were no potential negative consequences. All participants were expected to benefit from the outcomes of the study.

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection criteria for participants primarily included the absence of injuries, such as muscle or bone fractures, the absence of diseases, particularly chronic illnesses, and a regular training experience and fitness level, with a focus on speed endurance. The use of performance-enhancing supplements was also considered an inclusion factor.

3.5. Assessments

The researchers conducted an orientation for three assistants to establish assessment protocols prior to the test days. This included initial training, demonstrations, and feedback sessions. During the pre-tests (PTs), participants received motivation and corrections under the supervision of the researcher, ensuring consistent monitoring of activities.

To reduce variability, the same investigator handled both pre- and post-test (POT) measurements. All assessments were scheduled at the same time each day to minimize circadian variation. Additionally, participants were instructed to avoid intense exercise, caffeine, and alcohol for 24 hours before the PT (28, 29).

Physical and physiological assessments were conducted in field settings, evaluating key fitness components such as speed endurance, leg strength (LS), and strength endurance. Common tests included RE, LS, and maximal oxygen consumption (BalkeV̇O2Max) (30-32).

Running economy is the energy expenditure at submaximal speeds, which is crucial for running performance (33). To assess RE, course-specific time trials (TTs) were performed, including a 400 m sprint, a 1.5 km Kosmin speed endurance test, and a 3 km maximum speed trial. For the 400 m TT, resources such as cones and a stopwatch were used, with a 10-minute warm-up followed by timed runs under researcher supervision to minimize result variability (31).

Leg strength was measured using a tendon stiffness/reactive capacity test on a 400 m track with a marked 25 m section. Athletes began 10 to 15 meters behind the starting line, hopping on their dominant leg while the time between cones was recorded. This was repeated for the other leg, and the average time was calculated. Participants' ages were assessed via resting and exercise heart rates (31).

The BalkeV̇O2Max test required participants to run for 15 minutes on a 400-meter track, aiming to cover the maximum distance. The total distance was measured and rounded to the nearest 25 meters. V̇O2Max was estimated using the below formula:

V̇O2Max (mL/kg/min) = (((Total distance covered/15) - 133) × 0.172) + 33.3

The formula utilizes the distance covered in 15 minutes and applies the Frank Horwill equation. This approach provided insights into both critical indicators of physical fitness, including overall endurance and V̇O2Max (aerobic capacity) (31).

3.6. Training Protocol

The training protocol lasted for 32 weeks, spanning two seasons: December 2022 to April 2023 and December 2023 to April 2024. Utilizing the ATR (Accumulation, Transmutation, and Realization) block periodization system, the protocol was structured into three mesocycles: Accumulation (weeks 1 - 8), transmutation (weeks 9 - 20), and realization (weeks 21 - 32). Each mesocycle was tailored to participants' abilities and sports disciplines to optimize adaptation.

The detailed training program consisted of 3 sessions per week (96 sessions total) over 3 non-consecutive days. Each session lasted 45 - 60 minutes and was performed at an intensity of 50 - 70% of the participants' exercise capacity (28, 29). The intervention was supported by an observational checklist, with assessments conducted before, during, and after specific exercise parameters. These details are outlined in Table 1 (23, 24, 34).

| Training Variables | Day; Mode (Low to Moderate) of Load Distribution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | ||

| Week 32 | Session 96 | Methods | Volume/Time (min) | Intensity/HR | Rest/Set (Frequency) | Recovery/Reps |

| ITG | ||||||

| 4 | 12 | Test | 45 - 60 | 100% | 3’/1 | 2 - 3’/60” |

| 4 | 12 | Continuous | 45 - 60 | 163 - 166 bpm | No’/3 | 1’/15’ |

| 4 | 12 | Fartlek | 45 - 60 | 169 - 172 bpm | 2’/3 | 1’/15’ |

| 4 | 12 | Continuous | 45 - 60 | 162 - 165 bpm | No’/3 | 1’/15’ |

| 4 | 12 | Hill | 45 - 50 | 168 - 171 bpm | 2’/3 | 1’/5 × 5’ |

| 8 | 24 | Interval | 45 - 60 | 170 - 175 bpm | 2’/3 | 1’/3 × 5’ |

| 4 | 12 | Test | 45 - 60 | 100% | 3’/1 | 2 - 3’/60” |

| PTG | Resistance | Plyometric | Resistance | Plyometric | Resistance | Plyometric |

| 4 | 12 | Test | 45 - 60 | 100% | 3’/1 | 2 - 3’/60” |

| 8 | 24 | Squat/Lunges | 45 - 60 | 50 - 70% | 2’/10 | 1’/30” |

| 8 | 24 | Bound/Hop | 45 - 60 | 50 - 70% | 2’/8 | 1’/30” |

| 8 | 24 | Harness/Sprint | 45 - 60 | 50 - 70% | 2’/10 | 1’/30” |

| 4 | 12 | Test | 45 - 60 | 100% | 3’/1 | 2-3’/60” |

| CTG | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| 4 | 12 | Test | 45 - 60 | 100% | 3’/1 | 2 - 3’/60” |

| 8 | 24 | Conventional | 45 - 60 | 50 - 70% | No’/3 | 1’/15’ |

| 8 | 24 | Conventional | 45 - 60 | 50 - 70% | 2’/8 | 1’/30” |

| 8 | 24 | Conventional | 45 - 60 | 50 - 70% | 2’/3 | 1’/3 × 5’ |

| 4 | 12 | Test | 45 - 60 | 100% | 3’/1 | 2 - 3’/60” |

| Afternoon | Light | Light | Light | Light | Light | Light |

Abbreviations: ITG, interval training group; PTG, power (resistance and plyometric) training group; CTG, control training group; ’, minute per hour; ”, second; km, kilometer per distance; reps, repetition per set; bpm, beats per minute; HR, heart rate.

3.7. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), employing both descriptive and inferential methods. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and Levene's test was used to check for homogeneity of variances. Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated. A one-way ANOVA was performed to analyze mean differences among the three training groups: Interval training group, PTG, and CTG. The results showed statistically significant P-values (P < 0.05) and a large effect size (η²) for both PT to POT comparisons and group interactions. When significant differences were found, post hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction were used for pairwise comparisons.

4. Results

The primary objective was to compare the combined effects of interval and power training with a control group. Our key findings revealed significant improvements in strength endurance, speed endurance, and RE. Based on these key findings, the first null hypothesis was largely refuted in most physical (demographic and anthropometric) characteristics, as detailed in Table 2. The results from both descriptive statistics (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File) and inferential statistics, including paired sample t-tests, ANOVA, and multiple mean comparisons using Bonferroni correction (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File), support this conclusion.

| P | Dependent Variables | Between-Group Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Sig. | η² | ||

| 1 | Sex of participants (M/F) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | Fields of specialization (M/L) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| 3 | Chronological ages of participants (year) | 7.68 | 4.16 | 0.02 | 0.073 |

| 4 | Body height of participants (cm) | 0.003 | 3.24 | 0.04 | 0.058 |

| 5 | BM/W of participants (kg) | 2.59 | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.006 |

| 6 | BMI (kg/m2) | 0.50 | 3.54 | 0.03 | 0.063 |

| 7 | SST (mm) | 24.04 | 41.59 | 0.000 | 0.442 |

| 8 | FM/BFM/W (kg) | 110.96 | 228.57 | 0.000 | 0.813 |

| 9 | FFM/BLM/W (kg) | 138.02 | 11.58 | 0.000 | 0.181 |

| 10 | S/D BP (mmHg) | 5.15 | 33.55 | 0.000 | 0.390 |

| 11 | MTC (cm) | 1.65 | 14.03 | 0.000 | 0.211 |

| 12 | MS/CC (cm) | 0.84 | 6.86 | 0.002 | 0.116 |

| 13 | ULL (cm) | 1.03 | 5.17 | 0.007 | 0.090 |

| 14 | LLL (cm) | 3.56 | 25.42 | 0.000 | 0.326 |

| 15 | TLL (cm) | 1.67 | 6.14 | 0.003 | 0.105 |

Abbreviations: P, paired; M, mean square; F, variance inflation factor; η², eta squared (explains effect size); Sig, significant alpha P-value set at 0.05 levels; BM/W, Body Mass/Weight; BMI, Body Mass Index; SST, sum of 6 skinfold thickness; FM, fat mass; BFM/W, body fat mass/weight; FFM, fat free mass; BLM/W, body lean mass/weight; S/D, Systolic/diastolic; BP, blood pressure; MTC, maximum thigh circumference; MS/CC, maximum Shank (calf) circumference; ULL, Upper leg (thigh) length; LLL, lower leg (Shank) length; TLL, total leg (thigh & calf) length.

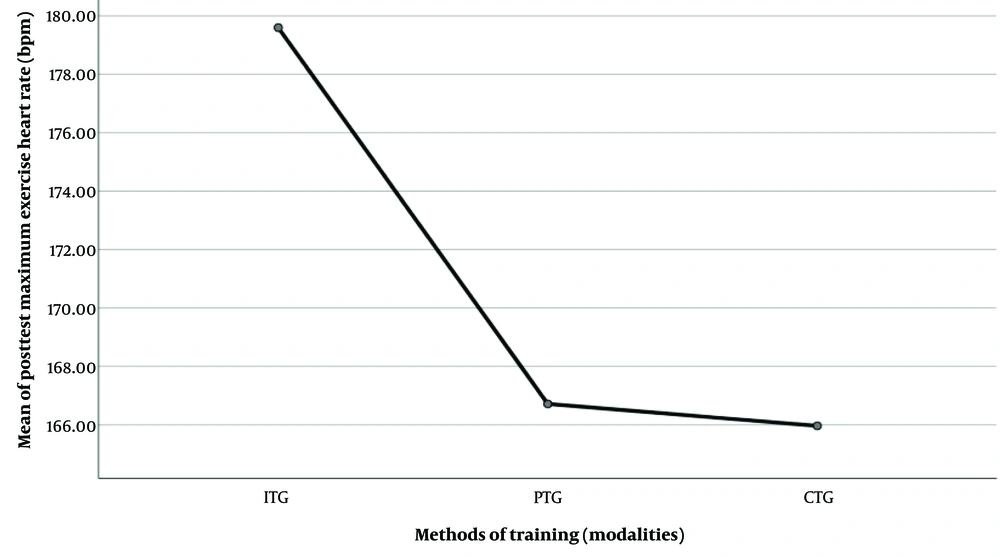

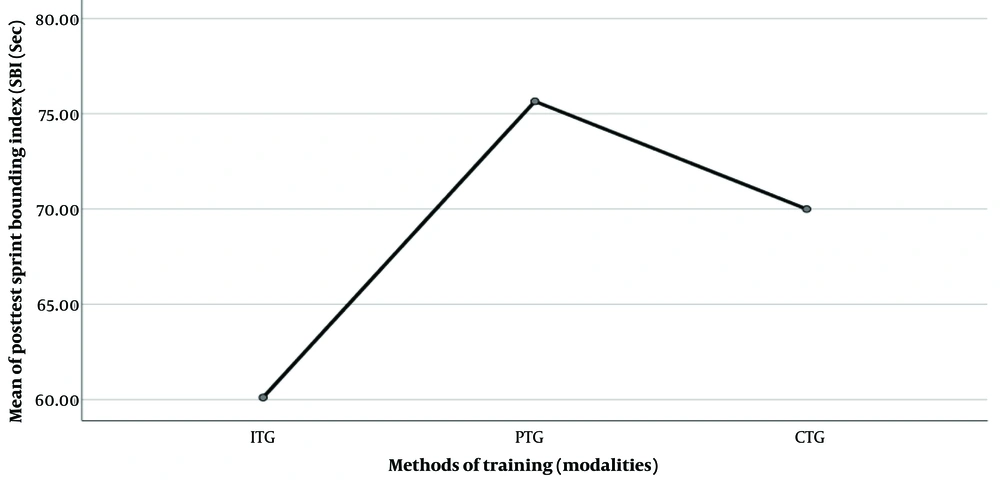

The second null hypothesis was rejected, as there were consistent improvements in most physiological characteristics related to RE. Notable improvements were observed in the following: Four hundred m sprint performance (108.83, P = 0.000), 1.5 km Kosmin speed endurance (38.39, P = 0.000), 3 km maximum speed TT (9.29, P = 0.000), maximum exercise heart rate (bpm) (23.40, P = 0.000) (Figure 2), LS (sec) (46.56, P = 0.000), and Sprint Bounding Index (SBI) (sec) (45.66, P = 0.000) (Figure 3). These results align with previous research, which indicates that interventions involving strength, interval, and combined training improve distance running performance (33, 35).

Conversely, some variables demonstrated a decrease in performance, including BalkeV̇O2Max (50.99, P = 0.000), leg press (38.42, P = 0.000), and squat (46.74, P = 0.000). This is supported by the pre- and post-test scores presented in Table 3, which show statistically significant differences in all performance metrics after the 32-week power intervention.

| P | Dependent Variables | Between-Group PT to POT Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Sig. | η² | ||

| 1 | BMI (kg/m2) | 0.50 | 3.54 | 0.03 | 0.033 |

| 2 | RHR (bpm) | 404.86 | 20.97 | 0.000 | 0.285 |

| 3 | MEHR (bpm) | 2112.96 | 23.40 | 0.000 | 0.308 |

| 4 | BalkeV̇O2Max (kg/mL/min) | 961.87 | 50.99 | 0.000 | 0.493 |

| 5 | Leg strength (s) | 12.38 | 46.56 | 0.000 | 0.470 |

| 6 | Leg press 1-RM (s) | 0.05 | 38.42 | 0.000 | 0.423 |

| 7 | Squat (s) | 688.15 | 46.74 | 0.000 | 0.471 |

| 8 | SBI (s) | 2226.82 | 45.66 | 0.000 | 0.465 |

| 9 | 400 m sprint performance (s) | 1201.21 | 108.83 | 0.000 | 0.675 |

| 10 | 1.5 km Kosmin speed endurance (s) | 18160.19 | 38.39 | 0.000 | 0.422 |

| 11 | 3 km maximum speed time trial test (s) | 2.28 | 9.29 | 0.000 | 0.150 |

Abbreviations: P, paired; PT, pre-test; POT, post-test; BalkeV̇O2Max, maximum oxygen consumption; kg/mL/min, kilograms per milliliters per minute; BMI, Body Mass Index; RHR, resting heart rate; MEHR, maximum exercise heart rate; SBI, Sprint Bounding Index.

The third null hypothesis was accepted, as most test variables related to training characteristics were not statistically significant, and small effect sizes were observed. From the third subgroup analysis, only sleep habits showed a statistically significant change (0.04, 3.43). Overall, the cumulative effects of our key findings across all three hypotheses indicate statistically significant changes (P < 0.05) with a large effect size (η² > 0.14) (Table 4).

| P | Dependent Variables | Between-Group Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Sig. | η² | ||

| 1 | LTA (m) | 0.000 | 0.004 | ||

| 2 | HSE (yes or no) | 0.000 | 0.010 | ||

| 3 | HIT (yes or no) | 0.000 | 0.003 | ||

| 4 | HPT (yes or no) | 0.009 | 0.21 | 0.82 | 0.020 |

| 5 | HS/TT (yes or no) | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.012 |

| 6 | TA/TE (year) | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.052 |

| 7 | Distance the last 8 months (km/w) | 3.77 | 1.09 | 0.34 | 0.002 |

| 8 | Distance the last 8 months (km/w) | 4.97 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.061 |

| 9 | Training sessions (no/day/week) | 5.38 | 2.89 | 0.06 | 0.002 |

| 10 | Number of rests (h/day) | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.011 |

| 11 | Habit of sleeping (h/day) | 4.57 | 3.43 | 0.04 | 0.010 |

| 12 | Habit of massage therapy (yes or no) | 0.009 | 0.13 | 0.88 | 0.004 |

| 13 | Safety habit of running surface with footwear (yes or no) | 0.04 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.010 |

| 14 | Intake habit of macro nutrient and fluid (gr/kcal/L/day) (yes or no) | 0.037 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: LTA, living and training altitude; HSE, habit of stretching exercise; HIT, habit of interval training; HPT, habit of power training; HS/TT, technique training; TA/TE, training experience.

a The analysis of the three dependent variables indicates that the aggregate value shows a significant effect. This suggests that both interval and power training methods positively influence physical, physiological, and training characteristics crucial for middle- and long-distance runners’ performance.

5. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the combined effects of interval and power training compared to the control group in POT results. Our main findings demonstrated significant improvements in participants' strength endurance, speed endurance, and RE, from both physical and physiological fitness perspectives.

To clarify our discussion, significant changes were observed in physical characteristics related to chronological age, BMI, fat-free mass, and maximum thigh circumference. These changes encompass both demographic factors (such as age, sex, culture, and cultural influences) and anthropometric factors (such as body type, structure, and genetic composition). However, no significant changes were noted in certain physical characteristics, such as sex, fields of study, and weight.

Similar to our findings, elite Ethiopian female runners exhibit an ideal combination of height, weight, and BMI. They have lower body weight and fat mass, with an increased lean muscle mass relative to their total body mass, which suggests an ectomorphic body type—an essential characteristic for running success (23, 33).

A separate study revealed that participants from East African countries, including Kenya and Ethiopia, make up less than 0.1% of the global population but consistently record the fastest race times. These runners are younger than their non-African counterparts (36).

In the 1960s, the Kalenjin ethnic group in Kenya and the Oromo ethnic group in Ethiopia emerged as dominant forces in long-distance running, often linked to a combination of genetic and cultural factors. Genetic studies have revealed variations in genes associated with body structure, circulatory and respiratory systems, energy metabolism, and calcium regulation. These genetic traits play a significant role in their running abilities (37).

After 32 weeks of combined interval and power training, significant improvements were observed in physiological characteristics, including LS (strength and speed endurance) and RE (speed and endurance) tests across all performance metrics, compared to the control groups.

These significant improvements were seen in 400 m sprint performance, 1.5 km Kosmin speed endurance, 3 km maximum speed TTs, LS, SBI (power and speed), and maximum exercise heart rate, all of which showed a large effect size (η² > 0.14).

Furthermore, our key findings indicate that middle-distance runners (0.8 - 3 km) and long-distance runners (5 - 42.2 km) from Kenya and Ethiopia demonstrate exceptional RE and excel in competitions at both national and international levels. Elite female long-distance runners from East Africa, such as Ethiopians and Kenyans, have shown remarkable endurance performance in the 12-minute Cooper test. Additionally, elite Black East African endurance runners from Eritrea, recognized as top athletes, display superior aerobic capacity and RE.

Anaerobic speed qualities benefit from ST, which has been shown to improve RE or TT performance by 2 - 8% over distances of 1.5 to 10 km. Various training factors—including intensity distribution, periodization, training volume, competition distance and frequency, training surface, footwear, running season, and topography—play a role in these improvements (7, 10, 13, 14, 16, 33, 38).

Interval training serves as a key indicator of fatigue recovery time and neuromuscular adaptations, such as peak torque (PT) and rate of torque development (RTD), which are measured after two sprints in a 5 × (2 × 30 m) repeated sprint protocol, as well as in knee flexor muscles (39-43).

Power training, which includes plyometric and strength exercises, maximizes type 1 muscle fibers and delays the activation of less efficient type 2 fibers during multi-joint, closed-chain high-load exercises such as the back squat. This training method enhances force and peak power output in elite middle- and long-distance runners. It improves speed development, boosts speed-related fitness, 3 km performance times, RE, muscle power, neuromuscular adaptations, and the dose-response relationship (24, 37).

Incorporating interval and ST into the weekly routine of Black East African female runners from Kenya and Ethiopia enhances both RE and performance. High-intensity IT improves aerobic fitness, muscular endurance, O2Max, strength, power, lean body composition, sprint speed, and RE TT performance among middle- and long-distance runners (6, 7, 11, 12, 15, 16).

Heavy resistance and strength training (HRST) are more effective than SET in increasing maximal strength, muscle power, anaerobic capacity, and sport-specific endurance. Short-term plyometric training produces comparable results across various sports and environmental conditions, whether at sea level or high altitude (39-41).

Optimizing biomechanical factors, favorable weather conditions, and running speed to improve running efficiency involves reducing the metabolic cost of running. Key factors such as ground contact time (GCT), stride length, stride frequency, joint angles, and foot strike patterns significantly affect running efficiency. Strategies like drafting, taking advantage of tailwinds, running downhill, and making footwear modifications can enhance performance. Efficient conversion of oxidative energy and the fractional utilization of V̇O2Max are critical for distance running success (39-41).

A 40-week strength-training program improves maximal and reactive strength, RE, and vV̇O2Max in competitive distance runners, without causing concurrent hypertrophy (42). Continuous interval aerobic training followed by ST significantly increases V̇O2Max and RE (43).

Resistance and plyometric exercises, when performed at low to high intensity, are an effective strategy for improving RE in highly trained middle- and long-distance runners. These workouts are recommended 2 - 3 times per week for a duration of 8 - 12 weeks. A meta-analysis on ST found a significant increase in elite runners' RE, with a standardized mean difference of 21.42 (95% confidence interval: 22.23 to 20.60) (44, 45).

However, in all three groups, certain physiological parameters, such as BalkeV̇O2Max (general endurance and speed endurance), leg press, and squat POTs, showed a significant decrease. Table 3 reveals discrepancies in the physiological parameters of Kenyan and Ethiopian middle- (0.8 - 3 km) and long-distance (5 - 42.2 km) runners, who demonstrate higher V̇O2Max levels, ranging from 72.6 to 81.9 ml/kg/min.

A comparison between Eritrean and Spanish runners showed similar V̇O2Max results (73.8 ± 5.6 mL/kg/min vs. 77.8 ± 5.7 mL/kg/min), with the upper limit of aerobic metabolism being higher for Eritrean runners. This performance is influenced by factors such as V̇O2Max, sustainable fractional utilization of V̇O2Max, lactate threshold (LT), blood lactate levels, and body composition, all shaped by neurobiological traits that promote habitual aerobic exercise (10, 16-18, 21, 46, 47).

In recent years, the combined effect of interval and power training methods has increasingly improved V̇O2Max, lowered resting heart rates, reduced blood pressure, and decreased fractional utilization at O2Max. Velocity at anaerobic threshold (vAT) has been shown to improve V̇O2Max, RE, and running speed in middle- and long-distance athletes (4-9, 11, 12, 15, 16).

In the majority of physiological characteristics, after the 32-week intervention, statistically significant changes and large effect sizes were observed in the experimental groups compared to the control group. The present study, when compared to previous studies in terms of training modalities, intervention period, P < 0.05, η² > 0.14, and the references indicated in Table 5, shows similar findings.

| S. No | Title | Training Modalities | Duration | P-Value | Effect Size (η²) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The effect of ST methods on middle‑distance and long‑distance runners’ athletic performance: A systematic review with meta‑analysis | ST | Total: 6 and 40 week, 1 - 4 sections/week | 0.029, 0.036 | Moderate: -0.469, large: -1.035 | (1) |

| 2 | Effects of HIIT and RT on physiological parameters and performance of well-trained runners: A randomized controlled trial. | HIIT and RT | 4 weeks | Δ: -2.3%, Δ: -1.6% | -0.62, -0.32 | (2) |

| 3 | Effects of continuous, interval, and combined training methods on middle- and long- distance runners’ performance | Interval and combined training | 12 weeks | 0.024 | 0.356 | (9) |

| 4 | ST for middle- and long-distance performance: A meta-analysis. | ST | - | 0.33 - 0.70 | 0.52 | (10) |

| 5 | Effect of ST programs in middle‑ and long‑distance runners’ economy at different running speeds: A systematic review with meta‑analysis | ST | Total: 6 and 24 week, 1 - 4 sections/week | 0.039, 0.018 | Small: -0.266, moderate: -0.426 | (33) |

| 6 | The effects of interval and continuous training on the oxygen cost of running in recreational runners: A systematic review and meta‑analysis | Interval training | 6 - 8 weeks | 0.28 | 0.04 | (48) |

| 7 | Effects of interval and power training on trained distance runners’ physical, physiological, and training characteristics | Combined interval and power training | Total 32 week, 3 sessions per week | 0.000 to 0.003 | Large: 150 to 675 | This work |

Abbreviations: HIIT, high-intensity interval training; RT, resistance training; ST, strength training.

Regarding the third training characteristic, except for sleep habits, the subgroup analysis of POT results showed a significant decrease after 32 weeks of observation (P > 0.05), but with a small effect size (η² < 0.01). Training-related factors, including living and training altitude, training habits (e.g., stretching, IT, power training, technique training), training experience, training volume, number of training sessions, recovery practices (e.g., rest, massage), running surface, footwear, and nutritional intake, all significantly increased.

In contrast to our findings, a small effect size favored fast training over low (moderate) intensities (defined as 60 - 79% of one-repetition maximum), with an effect size of 0.31 and a P-value of 0.06. Furthermore, strength gains between the conditions were not influenced by training or chronological age (2, 49, 50).

The observed training log of each runner's typical regimen over the past eight months considered altitude training, commonly practiced by elite endurance athletes at elevations between 1600 and 2400 meters. This approach introduces unique environmental stressors that enhance running performance in both altitude and sea-level competitions. Advances in nutrition and physiological interventions at elevations above 3000 meters, including the use of nutritional supplements, optimize adaptations to hypoxic conditions (39-41).

High-altitude living, rigorous training, low BMI, and low body fat all enhance endurance performance. However, nutritional strategies aimed at fat oxidation and weight loss may have unintended consequences. Instead, marathon training should provide adequate dietary energy, essential macronutrients, and important micronutrients like iron to support long-distance running success (40, 49, 50).

Optimal nutrition is crucial for competitive athletes, and endurance performance can be improved with carbohydrate-rich diets, proper hydration, glycogen storage, and carbohydrate and fluid intake during races. Factors such as unique dietary practices and specific anthropometric traits contribute to the dominance of East African distance runners (51).

Advanced footwear technology has enhanced endurance performance in distance running. Female runners recorded an improvement of 2 minutes and 10 seconds in their top 20 seasonal best times for longer events, translating to a 1.7% increase (52).

Engaging in long-distance running reduces the risk of chronic health issues. However, there is limited evidence for Ethiopian long-distance runners, who are encouraged to avoid lower extremity injuries by adopting preventive measures such as proper recovery, avoiding excessive training distances, and replacing running shoes in a timely manner. Managing competition factors such as distance and frequency, selecting appropriate training surfaces, and using proper footwear can minimize injury risk (53).

Finally, the post-test results of the CTG demonstrated less change across all subgroup analyses, including physical, physiological, and training characteristics of performance indices, compared to the ITG and PTG. However, the combined effects of interval and power training methods revealed significant changes in strength endurance, speed endurance, and RE.

5.1. Implications

A deeper understanding of these long-term effects is essential to maximize endurance performance.

5.2. Practical Applications

Customized training strategies based on these insights can help coaches and athletes enhance endurance capabilities effectively.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

This study faced several limitations, including the researchers' limited experience with performance metrics and statistical analysis, as well as inadequate research facilities, particularly in laboratory testing.

Future research could explore the interaction of these training methods with various factors such as exercise nutrition, exercise psychology, and footwear used during training and competition seasons. This may provide valuable insights that could support the development of future endurance running champions.

5.4. Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of combined interval and power training over a 32-week period. It explored multiple hypotheses and analyzed over 40 indices across three key constructs, demonstrating that this approach positively impacts strength endurance, speed endurance, and RE in middle and long-distance runners.