1. Introduction

The self-administration intake of AAS is a widespread practice in competitive bodybuilders. AAS abuse has been linked with numerous toxic and hormonal effects as well as structural changes in the myocardium (1, 2). Late gadolinium enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is an excellent non-invasive imaging tool, which allows an in-vivo characterization of the myocardial tissue (3). We present the case of a 39-year-old bodybuilder with a longstanding abuse of AAS presenting with increasing exertional dyspnoea and fatigue and showing signs of left ventricular hypertrophy in the echocardiography. We used CMR imaging in order to better identify the “histological” basis of the evident myocardial hypertrophy. Using CMR we could illustrate for the first time myocardial scarring following longstanding abuse of AAS.

2. Case Presentation

A 39-year-old bodybuilder with a more than 20 year history of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) abuse presented with increasing exertional dyspnoea and fatigue. The patient took AAS almost on a daily basis and he did not combine it with other anabolic agents such as growth hormone, stimulants and anabolic beta agonists. The exact regimen and dosage was unfortunately unknown. An ECG showed signs of left ventricular hypertrophy with positive Sokolow-Lyon-Index. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated a normal left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction 60%) with concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (septal wall thickness (SWT) was 15 mm and the posterior wall thickness (PWT) was 13 mm). There was no LV outflow tract obstruction at rest or after provocation. The patient´s past medical history was significant for an episode of congestive heart failure requiring hospitalization 3 years earlier. At that time, LV function was found to be severely impaired and coronary angiography revealed normal coronary arteries. The patient was started on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, diuretic and ß-blocker. His hospital course was complicated by a minor stroke that was found to be due to LV thrombosis. He was treated with phenprocoumon for a total of six months. Echocardiography revealed complete resolution of thrombus and improvement of LV systolic function during follow-up.

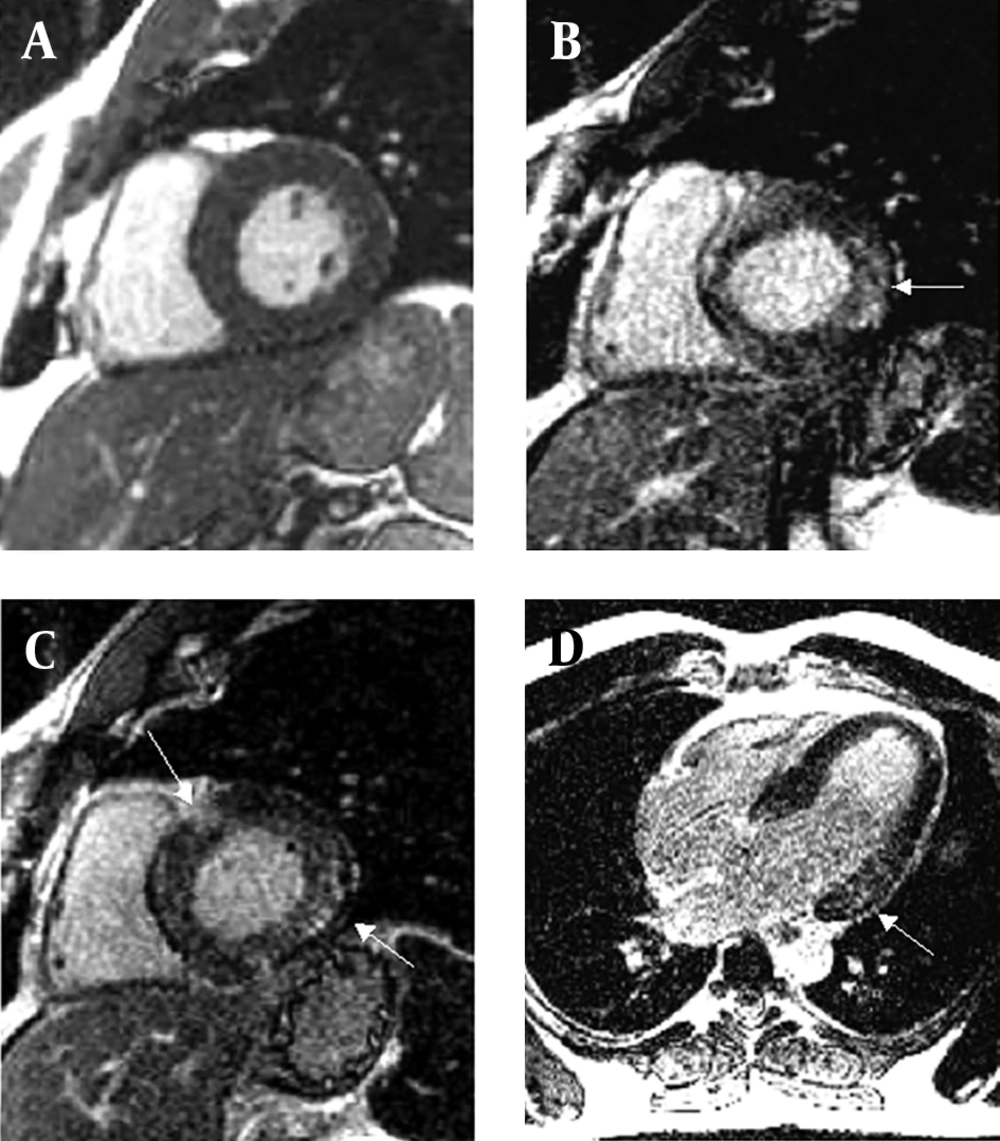

Diagnostic work-up of the patient´s current symptoms included a cine cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). CMR demonstrated a non-dilated but severely hypertrophied left ventricle (end-diastolic volume 178 mL, myocardial mass 324g) with normal systolic function (Figure 1 A). Using a T1-weighted inversion-recovery sequence 10 minutes after application of 0.1 mmol/kg gadolinium with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (gadolinium DTPA), patchy midwall enhancement in the septal and posterolateral region of the left ventricle was demonstrated (Figure 1 B, C, D). This enhancement pattern is different from the enhancement pattern found in patients with ischemic heart disease which invariably involves the subendocardium and typically occurs in the territory of a coronary artery.

A: Precontrast diastolic long-axis cine image obtained with cine cardiovascular magnetic resonance demonstrating a non-dilated but hypertrophied left ventricle (end-diastolic volume 178 mL, myocardial mass 324g) with normal systolic function. B,C,D: Post-contrast short and long axis images. Using a T1-weighted inversion-recovery sequence 10 minutes after application of 0.1 mmol/kg gadolinium with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (gadolinium DTPA), patchy midwall enhancement in the septal and posterolateral region of the left ventricle was demonstrated (arrows).

3. Discussion

The present case illustrates for the first time, by CMR, myocardial scarring with severe left ventricular hypertrophy in a patient with normal coronary arteries after long lasting abuse of AAS. Those changes are unlikely to be due to coronary vessel disease because the patient had a coronary angiography 3 years ago which revealed normal coronary arteries. Furthermore we could demonstrate that the enhancement pattern found in our case using cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging is different from the enhancement pattern found in patients with ischemic heart disease which invariably involves the subendocardium and typically occurs in the territory of a coronary artery.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), Fabry disease and Amyloidosis could also be considered as a differential diagnosis to our case. Nevertheless the findings of the CMR imaging do not really match either HCM or Amyloidosis. In addition because of the young age of our patient amyloidosis seems to be very unlikely. Our patient did not have the typical symptoms or the clinical phenotype for Fabry disease. The α-Galaktosidasea activity was also within the normal range.

The self-administration intake of AAS is a widespread practice in competitive bodybuilders. Beside the numerous toxic and hormonal effects, primarily LV hypertrophy with restricted diastolic function is well documented (1, 2). Furthermore, it has been shown that strength athletes who use AAS show significantly different cardiac dimensions and biventricular systolic dysfunction and impaired ventricular inflow as compared to non-athletes and non-AAS-using strength athletes (4).

Anabolic-androgenic steroids abuse has been shown to affect the cardiomyocyte survival and heart function in cell cultures, animal models and humans. It has also been reported that high-dose AAS treatment in small animal models is associated with interstitial collagen deposition and fibrosis. Fibrosis is assumed to occur initially as an adaptation in myocardial hypertrophy to preserve the function of the ventricles and, thereafter, as a repair mechanism to compensate apoptotic myocardial cell loss. In one study on rabbits treated with daily oral high doses of AAS for 3 months, the AAS-treated group showed myocardial interstitial fibrosis associated with higher caspase-3 activity. Local RAS activity which has been shown to be activated in high-dose AAS treatment in rats induces interstitial fibrosis and has been shown to be a key signaling pathway for heart failure (5). Cardiac MRI allows a much more comprehensive non-invasive assessment of cardiac structure and function, as well as detection of perfusion defects, inflammation and/or fibrosis existing within the cardiac muscle of AAS users (6).

The present case illustrates for the first time, by CMR, myocardial scarring with severe left ventricular hypertrophy in a patient with normal coronary arteries after long lasting abuse of AAS. The enhancement pattern is different from the enhancement pattern found in patients with ischemic heart disease. With that finding we could demonstrate a link between AAS abuse and the occurrence of myocardial scarring in humans. This finding may help raise awareness of the consequences of AAS use.