1. Context

The incidence of low back pain (LBP) in young athletes has been reported in a wide range in literature, including numbers as low as one to as high as thirty percent (1-3). Many factors such as kind of sport, gender, training intensity, frequency and technique affect the rate of low back pain in athletes (4-7). In spite of the self-limiting nature of disease in most cases, many athletes experience long lasting symptoms which could affect their professional life (5, 8, 9). The most common cause of LBP in athletes is degenerative disc disease (DDD) and sponylolysis (10-14). Finding the exact cause of pain in athletes is not always feasible and it may create challenges for treating physicians in both diagnosis and management (10). Therefore, physicians should lead a comprehensive approach to the patient with LBP and need to keep in mind the less common causes of LBP in athletes such as stress fracture of sacrum or facet joints (11).

1.1. Epidemiology

LBP is a symptom and not a diagnosis; therefore, it is important to interpret the epidemiology of LBP in athletes in the light of this important point. It is also important to take into account that LBP is self-limiting in many patients and thus it is difficult to attribute this to a known underlying abnormality (4, 10) LBP is a common cause of lost playing time in competitive athletes. Low back pain is an important and common cause of missing games in athletes (11-15). According to McCarroll et al. (12), 30% of football players (44 of 145 college football players) lost playing time due to LBP (12). According the literature review, the prevalence of LBP in athletes has been reported between 1% to 30%, and also, 10-15% of all sport injuries are low back injuries (16-19). Granhed et al. reported that the prevalence of LBP in wrestlers was significantly higher than the age-matched population (59% vs 31%) (3). According to Sward et al. LBP in elite gymnasts was higher than control group (79% vs. 38%) (11). In other sports, LBP has lower incidence and the prevalence of LBP in soccer, tennis, football, golf and weightlifting has been reported to be 30-40% (21, 23). In some types of sports, for instance in gymnasts and wrestlers LBP is more common and reported 70% and 59% respectively (3, 8, 11, 12). Likewise Hainline et al. reported that 38% of professional tennis players missed at least one tournament because of LBP (13).

1.2. Differential Diagnosis

Both spinal and non-spinal cause of LBP must be considered in evaluating the athletes with LBP (14-17). Table 1 shows etiologies of LBP which could be intrinsic to spine or related to pathology in adjacent organs. Therefore, a broad spectrum of differential diagnoses should be considered. However, in this review we focused on the two most common causes of LBP in athletes, namely, degenerative disc disease, and spondylolisthesis.

| Spinal Causes | Adjacent Organs |

|---|---|

| Muscle strain/ ligament sprain | Pelvic organs (e.g. ovarian cysts) |

| Degenerative disc disease | Renal disease |

| Isthmic spondylolysis/ listhesis | SIJ dysfunction |

| Ring apophyseal injury (adolescents ) | Hip pathology |

| Stress fracture of sacrum/facet (14) | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Disc herniation | |

| Fracture of vertebrae | |

| Infection | |

| Tumors | |

| Sacralization of L5 |

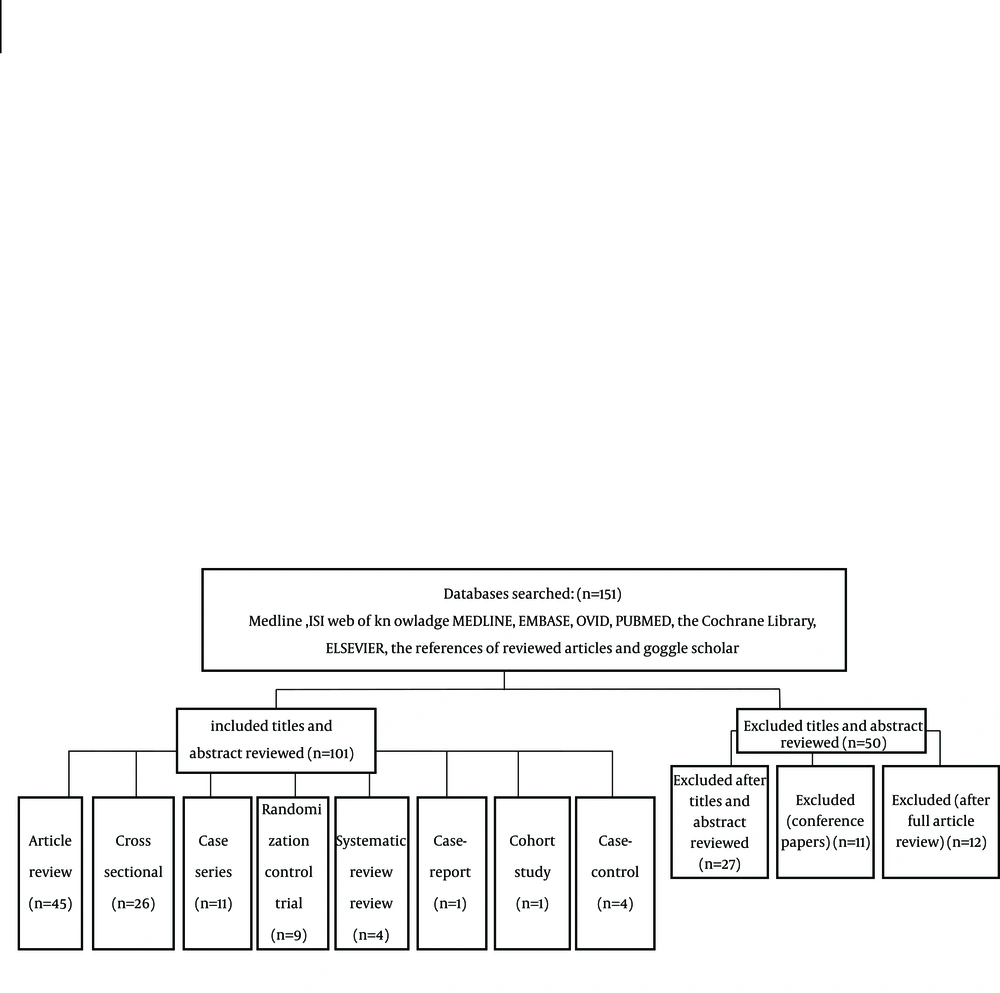

2. Evidence Acquisition

A literature search was performed for the years 1951 through 2013. Keywords used were Low Back Pain and Athletes. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, OVID, PUBMED, the Cochrane Library, ELSEVIER, and the references of reviewed articles, for English-language of Low Back Pain in Athletes. RCT (n=9), case control (n=4), review article (n=45), cohort (n=1), systematic review (n=4), case series ( n=11), cross sectional (n=26), and case report (n=1). Exclusion criteria were papers presented in the conferences and papers without full text and articles that had been written in other languages except english (Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. Degenerative Disc Disease

The exact relationship between degenerative disc disease (DDD) and LBP remains unclear because many radiographic findings of degenerative disc disease are found in the asymptomatic general population (18). Micheli et al. reported that acute disc herniation occurs in only 11% of young athletes with LBP (17).

Pathogenesis: According to the available literature, stress within the anulus can cause tearing within it (19). Circumferential tears occur first, and with continued stress these can progress to radial tears, which is detected as a High inTensity Zone (HIZ) by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (19-25) or as leakage of contrast medium within the posterior aspect of the annulus on a discogram (19, 25, 26). At this stage plain radiographs demonstrate a mild decrease in disc height, MRI can reveal decreased signal intensity in the disc, and these changes result in more loads on the posterior facet joints, subsequently causing degeneration of the articular surfaces. With time, advanced degenerative changes, such as osteophyte formation in both the disc and the facets, are an attempt at autostabilization (18, 19). Several studies have characterized nociceptive micro-innervation of anterior and posterior aspect of the annulus and facet joints (21-23).

3.1.1. Degenerative Disc Disease and Sports

Every sport places unique demands on the lumbar vertebrae and consequently, the intervertebral disc (27-29). Hosea et al. showed that a golf swing, a primarily torsional activity, produces 7500 and 6100 N of compressive force across the L3-L4 disc in professional and amateur players (30). Hosea and Hannafin also estimated maximal lumbar compressive force to be about 6100 N in rowers (31). According the studies of Gatt et al. (32) and Cholewicki et al. (33) who measured forces in L4-L5 motion segment during blocking maneuvers in 5 football linemen and 57 competitive weight lifters, respectively, the average peak compressive load was > 8600 N and > 17000 N. Cappozzo et al. found that during half-squat lifting of a weight about 1.6 time of body weight compressive load across the L3-L4 motion segment was about ten times body weight (approximately 7000 N for an average 70 kg personal). These studies showed that increasing lumbar flexion was the most effective coincidence (34). According to the Sward et al. (11) and Ong et al. (35) studies participation in sport is a probable risk factor for development of disc degeneration. Sward et al. (11) showed that in 75% of elite gymnasts degenerative radiographic changes in lumbar spine was detected, contrary to 31% of control group. Similarly, Ong et al. (35) reported degenerative changes in 58% of athletes compared with 38% of control group, and this degenerative change was more prominent at L5-S1 disc (the most affected level was L5-S1 disc). Other factors that may accelerate disc degeneration are type and intensity of the sports (29, 35-37). Sward et al. demonstrated that DDD was more common in male gymnasts than players in other sports (38). Bartolozzi et al. (5) showed that although the radiographic evidence of degenerative changes was more common in volleyball players with improper technique than in those who used proper technique (62% vs 21%), the rate of LBP was not higher in the former group (5). Videman et al. (1) showed that degenerative changes were more common in weight lifters compared to football players and also in the former the upper lumbar levels were more affected while in the later, lower lumbar levels (1, 39, 40). According to the studies of Lundin (9), Sward (11), Kujala (7), Ogon (36), and Videman (1), there is an association between imaging findings and the LBP (1, 9, 11, 41, 42). They found that decreased disc-space height in X-Ray, decreased signal intensity within the disc on MRI, ring apophyseal injury in X-Ray, severe end-plate degeneration and disk degeneration on MRI, were the most correlated imaging findings with LBP.

3.1.2. Treatment

Most patients improve with non-operative treatment because the majority of athletes with LBP have a benign source of pain (37, 43-45). There are many different modalities for non-operative treatment including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), heat, ultrasound laser therapy, NSAIDs, steroids, manipulation, traction, injections, acupuncture, massage, back school, and exercise, with different recommendations in the literature (37, 43, 44, 46-49). Heat can be applied to the low back pain with water bottle and bath, hot packs, steam, saunas, and electric pads. There is moderate evidence according to the Cochran review, that support effectiveness of heat in reducing acute and sub-acute low back pain. With addition of exercise, pain can be further decreased, (50) specially if superficial heat is applied in the first week (51, 52).There are no systematic and Cochran reviews for ultrasound (53-55). Only one small nonrandomized control trial has shown that ultrasound is more effective than pain killers in reducing pain in patients with acute low back pain (53). A Cochran review of small studies found insufficient data to support the effectiveness of laser therapy in low back pain which is result of the heterogenicity of populations, dosage, and technique of laser application (56). A large Cochran review of 65 trials of NSAIDs and COX-II inhibitors in treatment of low back pain found that both of them were more effective than the placebo in reducing pain in patients with acute and chronic low back pain. Although both of them have many known side effects, NSAIDs have more traditional side effects and COX-II inhibitors have potentially more cardiovascular side effects (57). There is no clear evidence about the effectiveness of antidepressant drugs and opioids in treatment of acute and chronic low back pain (58, 59). According to the three high quality trials, systemic steroids were not more effective than placebo in treatment of low back pain (60, 61). In patients with low back pain without radicular pain the effect of a single dose intramuscular injection in pain relief through a month was the same as placebo (61). A Cochran review of 20 randomized control trials (RCTs) (total population = 2674) for spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for treatment of acute low back pain found that SMT was not more effective than other recommended therapies and interventions (62). A Cochran review of 32 RCTs (total participants= 2762) for traction in low back pain with or without sciatica indicated that traction, either alone or in combination with other treatments, has little or no impact on pain intensity, functional status, global improvement and return to work among people with LBP. There is only limited-quality evidence from studies with small sample sizes and moderate to high risk of bias. The effects shown by these studies are small and are not clinically relevant (63). A Cochran review of 18 RCTs of 1179 participants for injection therapy for sub-acute and chronic low back pain showed that there is no strong evidence for or against the effectiveness of injection of steroid, local anesthetics, indomethacin, sodium hyaluronate and B12 in treatment of low back pain (64). There are low to very low-quality evidence for effectiveness of Botulinum injection in treatment of low back pain in a 2011 Cochran review (65). A Cochran review of 35 RCTs for effectiveness of acupuncture for acute low-back pain did not conclud firmly that it reduced pain, however, for chronic low-back pain, acupuncture is more effective than no treatment immediately after treatment and in the short-term only. The data suggest that acupuncture and dry-needling in combination with other therapies may reduce pain in chronic low-back pain and it is not better than conservative treatment (66). According to a Cochran review of 13 RCTs, massage might be useful in patients with sub-acute and chronic non-specific low-back pain, especially in combination with other modalities such as exercise and education (67). The insufficient strong evidence shows that acupuncture massage is more beneficial than classic massage, but this needs more studies and confirmation (66). There is moderate evidence suggesting superiority of back schools over other conservative treatments in reducing pain (68). A Cochran review showed that in an occupational setting, back schools were more effective than exercise, manipulation, myofascial therapy or advice; and placebo in decreasing pain, returning to work and improving function in patients with chronic LBP status, in the short and intermediate-term (68, 69). A Cochran review of 61 RCTs found that exercise in acute low back pain had the same effect on low back pain in comparative to no treatment or conservative therapy. In chronic low back pain, exercise, reduced pain slightly and in subacute low back pain there is weak evidence regarding effectiveness of exercise in decreasing pain (70). Table 2 describes strength of recommendation for these modalities.

| A | B | C | Expert Based Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manipulation (69,70) | Heat (71, 72) | Acupuncture (73) | TENS (74) |

| NSAIDS (75) | Exercise (76) | Back school (76) | Traction (77, 78) |

| Corestabilization (72, 73, 79) | Low-level laser therapy (80) | Ultrasound (68, 77, 80-82) | |

| Muscle relaxants (70, 79, 83, 84) | Massage (77, 85) | ||

| Opioids (86) | Steroid (87-90) | ||

| Antidepressant (91, 92) | |||

| Injection (93) | |||

| Bracing (80) |

3.1.3. Operative Treatment

The main indications for surgical treatment in athletes with LBP are pain correlated with imaging studies, and failure of conservative treatment after 4-6 months (37, 43, 44). Various surgical options have been described to decreased pain. These consist of posterolateral fusion, interbody fusion (ALIF, TLIF, PLIF, and XLIF) techniques, 360 degrees fusion (Anterior and posterior). Literature review shows that fusion rate with interbody fusion technique is higher than posterolateral technique (73, 85, 88, 89, 94). Whoever the effect of this on longterm outcome is elusive (39-52). Because it has been thought that the pathology of DDD is in the disc, more surgeons prefer inter body fusion techniques. In some studies good or excellent results have been reported (73, 76, 89, 94).

3.1.4. Return to Play

The main concern for athletes with LBP is return toplay after either conservative or operative treatment. There is lack of evidence concerning the optimal time of return to play (44, 95, 96). There is only some evidence regarding optimal time of return to play that are based on expert opinions (44, 95). According to an expert opinion guideline on return to play (RTP), patients with LBP undergoing conservative therapy should achieve full range of motion of spine and at least 80% of muscle strength before return to play (44, 95). For patients with persistent pain nonresponsive to conservative treatment, progressive listhesis or developing neurologic deficit surgical treatment must be considered. There are many different surgical technique options in patients who are candidates for surgical treatment, from simple posterolateralinsitu fusion with or without instrumentation, to more advanced and complicated surgical technique such as neurologic decompression accompanied by circumferential fusion. Description of these techniques in details is beyond the scope of this article. Athletes who underwent fusion with any kind of surgical technique should wait at least one year until radiographic evidence of union is revealed before RTP (44, 95). If conservative treatment failed to reduce pain in athletes, surgical treatment is indicated. There are a wide variety of surgical techniques, however, the two most common surgeries which are discussed more in this article, are microdisectomy and fusion techniques either posterolaterally or interbody fusion techniques (44, 95).After spinal fusion due to discogenic pain as a result of degenerative disc disease, the athletes should wait one year before returning to play (44, 95, 96). Many surgeons advise the athletes to avoid participating in contact sport after fusion (96). Iwamoto et al. reported that 79% of athletes with disc herniation returned to play following conservative therapy in an average time of 4.7 months, and 85% of those treated surgically returned to activity in 5.2 to 5.8 months (96). Most authors believe that athletes should wait until there is radiographic evidence of fusion, complete or nearly complete relief of pain and achievement of more than 80% of strength, flexibility and endurance of spinal muscle and spine, before they return to previous activity level (44).

3.2. Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

Generally speaking spondylolysis is a bony defect ofpars inter-articularis and classified to three subtype of stress fracture, acute traumatic fracture and elongated pars, that is a result of recurrent micro fracture of pars due to micro trauma and subsequent micro motion and union and repeated this event in the life time (72, 74, 97, 98). The most common sites of spondylolysis are L5 (in 85-95% of cases) and L4 (in 5-15% of patients) vertebra (72, 81, 98, 99). Most cases are detected incidentally because ofthe asymptomatic nature of disease 25% of symptomatic patients may develop spondylolisthesis (79). In some sports the prevalence of spondylolysis seems to be higher. According to the Rossi and Dragoni study prevalence of spondylolysis in divers, wrestlers and weight lifters was 43%, 30%, and 23%, respectively (75). Soler and Calderon (82) reported a prevalence of 27%, 17%, and 17% in throwing athletes, gymnasts, and rowers, in the same order (82). In terms of clinical manifestation LBP is the most common symptom. Some patients may report radicular pain and hamstring tightness (82). In physical examination, hyperextension of lumbar spine increases the pain, in inspection of the patient who is standing, hyperlordosis of lumbar spine is evident which could be a result of spondylolisthesis or exaggerated pelvic incidence and sacral inclination with higher grade spondylolisthesis, heart shaped buttock, step off on lower back, point tenderness, positive straight leg raise test due to either hamstring tightness or nerve root tension may exist (82, 100). Neurologic examination is usually normal (44, 82, 100).

3.2.1. Diagnosis

For diagnosis of spondylolysis in athletes, high suspicion of physician is necessary (44, 90, 93). Radiographic modalities start with AP, lateral and Right and left oblique of lumbosacral junction (90). Another useful view is coned-down lateral X-Ray of lumbosacral junction by which 85% of spondylysis is appreciable (98). Spondylolisthesis has been classified by myerding (71), as grade I indicating < 25%; grade II, 25-50%; grade III, 50-75%; grade IV, 75-100% and grade V, spondyloptosis (79, 98).When plain radiographs in suspected patients fail to detect the spondylolytic defect then more sophisticated modalities such as bone scan, single- photon- emission computed tomography (SPECT), or MRI should be used (100). SPECT also is useful in differentiating symptomatic from asymptomatic pars defects (100). CT scan is more sensitive than plain X-Ray. By CT scan differentiation between acute (fresh fracture site edges) and chronic pars defect (with sclerotic and blunt edges) is feasible. In a patient with LBP and suspected spondylolysis and negative X-Ray, SPECT should be recommended. If SPECT is positive then CTscan for appreciation of chronicity of pars lesion should be performed (83, 100, 101).

3.2.2. Treatment

Most patients with spondylolysis improve with conservative treatment (90). Non-operative treatment includes short-term rest and/or brace followed by physiotherapy (44, 90, 93). In most cases symptomatic patients are successfully managed with non-operative measures (80, 84, 92). For adolescent athletes with persistent symptoms despite conservative therapy surgical treatment, pars repair, in situ posterolateral fusion, interbody fusion techniques, and circumferential fusion produce satisfactory results (44, 90).

4. Conclusions

LBP in athletes is common and has a broad spectrum of differential diagnoses that must be taken in to account when a clinician approaches the patient with LBP. The physicians should take into account spinal and extra-spinal causes of low back pain in athletes. The two most common causes of LBP arising from the spine, in athletes are DDD and spondyloysis with or without listhesis (14-17). Although most atheletes, with LBP whether resulting of DDD or spondylolysis respond well to conservative treatment (44), there are many options for nonsurgical treatment which have been discussed in detail with the last evidence regarding their effectiveness in reducing pain in patients complaining of LBP. When conservative treatment failes, surgical treatment is indicated. On the other hand, intractable pain, progressive listhesis in spite of conservative treatment, or development of neurologic deficit, especially if it is progressive, are the surgical indications in athletes (37, 43, 44). There are different kinds of surgical technique, including simple posterolateral fusion, interboby fusion techniques (PLIF, TLIF, ALIF, and XLIF), and circumferential fusion. Recently, minimaly invasive techniques instead of conventional techniques are developing fastly, which might have benefits for athletes to return to play earlier in comparison to conventional techniques. However this concept needs large future trials (73, 85, 89, 94). It should be emphasized that with any kind of surgical technique the patients need time for fusion and healing, which is a year according to most references (44, 95). The major concern in athletes with LBP is return to play and previous level of their activity after treatment. There is insufficient data regarding this issue in literature to define the optimal time to return to play following treatment. To our knowledge some authors recommend (44-50, 73, 85, 89, 94) return to play when: the athletes are pain free, when they have near normal function of spine in terms of muscle strength, flexibility and endurance (44).For patients who underwent fusion whether due to DDD or spondylolysis, with any kind of surgical technique, either conventional or new minimaly invasive techniques, RTP guidelines recommend waiting time of at least one year before return to play (44, 50, 93, 95). Most authors believe that when athletes are pain-free they can return to play, regardless of whether there is radiographic evidence of pars healing (83, 90, 101). According to RTP guidelines patients with spondylolysis and low grade spondylolisthesis (grade I) should rest 4-6 weeks and then achieve full range of motion before return to play (44).