1. Background

According to recent studies, contracting muscles release various cytokines called myokines. This finding has opened a new insight on the role of cytokines in modulating the muscle’s metabolic and immunological responses to exercise (1). One cytokine, interleukin (IL)-15, has recently received more attention with regards to its influence on muscle tissue. This cytokine was initially considered to act as a growth factor for natural killer cell development (2). IL-15 was subsequently found to be highly expressed by skeletal muscle fibers (3). This cytokine has been shown to exert hypertrophic action in skeletal muscles in experimental models (4, 5), increase deposition of lean body mass and bone mineral content, reduce body fat and modulate body composition (6).

Skeletal muscle is a principal depot for both IL-15 mRNA and protein, which may be translated or released upon appropriate physiological stimuli (6). In human skeletal muscle cell cultures, IL-15 induces an accumulation of myosin heavy chain protein in differentiated myotubes, therefore suggesting that IL-15 contributes to muscle growth as an anabolic factor (7-9).

In order to exert effects on muscle and bone tissue, IL-15 must be released into the circulation (6). In various studies, failure to release IL-15 has been reported after aerobic exercises; however, the effect of resistance exercise (RE) on IL-15 response is controversial (10-12). Riechman et al. (10) have reported changes in circulating levels of IL-15 immediately after an all major muscle RE protocol. These authors hypothesized that post-exercise IL-15 release in muscle fiber occurred via micro-tears. In contrast, Ostrowski et al. (12) did not observe an alteration in IL-15 plasma levels in response to 2.5 hours of treadmill running, nor were there alterations in skeletal muscle mRNA levels immediately following a three-hour run, (13) nor in a two hour bout of weight training (11).

Different observations in cytokine responses to exercise are predominantly related to the intensity, mode and duration of exercise in addition to the participants’ fitness levels, although differences in sensitivity and specificity of the assays should be considered. Acute bouts of intense or prolonged RE can induce an inflammatory response (14).

2. Objectives

In this study we have sought to determine whether IL-15 is mainly released in all major muscle groups following eccentric (ECC)-emphasized intense RE, which causes the induction of micro-tears, or whether it is released following concentric (CON)-emphasized RE. Given the important role of IL-15 with regards to muscle growth and the influence of various stimuli, in particular RE, on the release of this cytokine, we have evaluated the effects of two different (CON and ECC) RE modes and fitness levels of participants on IL-15 release into the circulation. Simultaneously, we measured tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and white blood cell (WBC) numbers as markers of inflammatory responses.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Subjects

Out of 48 male volunteers, we selected 28 healthy subjects (14 athletes and 14 non-athletes) that had normal calorie consumption, no history of anabolic intake, or any history of inflammatory, cardiovascular, endocrine, or muscle disorders. The mean age of athletes was 24.1 ± 2.5 years; for non-athletes it was 20.8 ± 2.3 years. Athletic subjects had more than three hours RE per week during the past six months, whereas non-athletes had not taken part in any regular physical activities. We measured subjects’ anthropometric characteristics (e.g., height, weight, body fat percentage, and arm and leg circumferences) one week before they began RE. All subjects had a normal diet, sleep and calorie consumption. We asked subjects to refrain from participating in any RE and/or intensive exercise outside of the study program. The purpose and possible risk of the protocol was explained to each subject before participating and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

3.2. Blood Sampling and Analysis

Subjects’ blood samples for WBC count and serum were obtained before and immediately (1-5 minutes) following RE. WBC count was performed by the Beckman Coulter hematology analyzer (USA). Sera were isolated and stored at -20°C until use. Measurement of IL-15 serum levels was performed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sensitivity of test was 0.2 pg/mL. TNF-α and hs-CRP levels were measured by IBL Company ELISA kit (Hamburg, Germany) as described by the manufacturer. The sensitivity of the tests was 2.3 pg/mL and 0.02 µg/mL, respectively.

3.3. Eccentric and Concentric Resistance Exercise Protocol

The non-athlete group underwent a two week, four sessions training period to familiarize themselves with the program. One week before the program we determined the baseline one repetition maximum (1 RM), body mass index (BMI) and other anthropometric data for all subjects.

Subjects participated in two sessions of ECC and CON emphasized RE with 4 days interval. Sessions consisted of seven exercises that focused on all major muscle groups at weight loads of 70% - 80% of 1RM for CON and 90% - 100% of 1RM for ECC on an RE instrument (Tecknojim, Italy). As in previous studies, a 20% - 50% heavier relative load than the load for CON training was suggested as an equivalent load for ECC training (15).

In order to emphasize the ECC and CON phases of contraction in any movement, individuals (2:1 or 3:1 ratio) assisted subjects by carrying the weights in the ECC or CON phase. During the first session participants only exercised in the CON phase as follows: in the squat position they actively lifted the weight, after which an assistant lowered the weight and the participants remained inactive. In this session participants also were inactive during the ECC phase of movement.

The RE program included the following exercises in the ECC and CON sections that could be performed separately on the RE instrument: squat, chest press, seated row, leg extensions, triceps extensions, arm curl, shoulder press, and hamstring curl. Before each bout of exercise, participants were instructed to perform 10 to 15 minutes of warm-up exercises that consisted of running for 5 minutes at a 40% - 60% heart rate reserve (HRR) followed by 10 minutes of static stretching. The exercise protocol consisted of three sets of 8 - 10 repetitions followed by a 60 seconds rest interval between each set and 1 - 2 minutes between exercises.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 16 was used to analyze the data. Quantitative variables were described using mean ± standard deviation. The paired sample t-test and independent sample t-test were performed for comprising inters and between group differences and Pearson correlation was used for analyzing possible relationship between variable changes. The level of significance was set at 0.05 for all statistical analyses.

4. Results

This study compared serum IL-15 levels in an ECC and CON emphasized RE model in two groups, athletes and non-athletes. The physiological and anthropometric characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between athletes and non-athletes in parameters of age, BMI, height, weight, and body fat.

| Variables | Athletes | Non-Athletes |

|---|---|---|

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.8 (2.1) | 21.6 (2.6) |

| Age, y | 24.1 (2.5) | 20.8 (2.3) |

| Height, cm | 178.3 (5.3) | 177.5 (6) |

| Weight, kg | 75.8 (6.8) | 68.4 (7.5) |

| Body fat, % | 14.5 (4.1) | 15.2 (6.7) |

a The values are presented as mean ± SD.

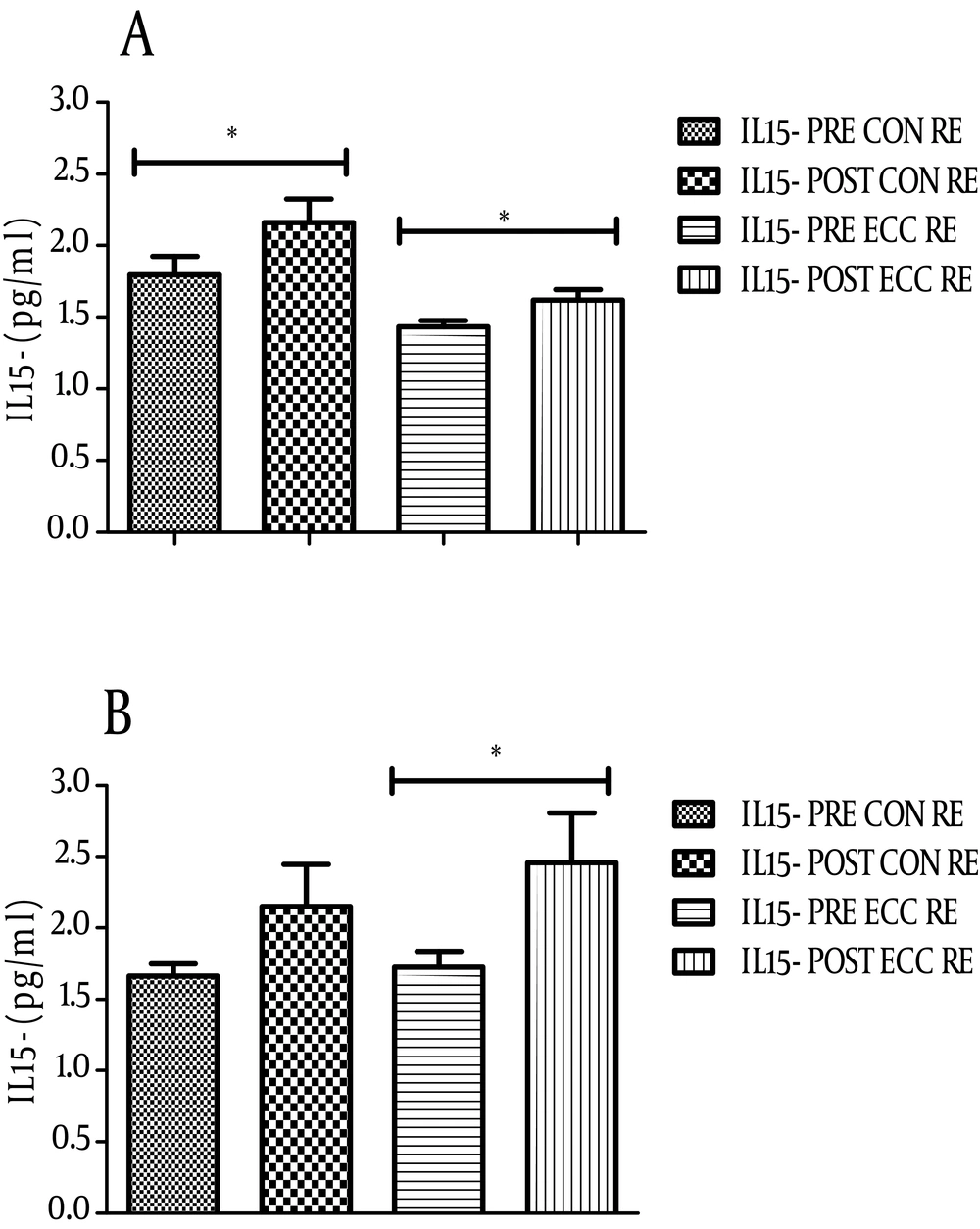

4.1. IL-15 Response to ECC and CON RE

IL-15 serum levels significantly increased after ECC emphasized RE in both groups. The level of this cytokine changed from 1.43 ± 0.17 to 1.62 ± 0.28 pg/mL (P = 0.002) in non-athletes (Figure 1A) and from 1.72 ± 0.4 to 2.46 ± 1.3 pg/mL (P = 0.01) in athletes after ECC RE (Figure 1B). With respect to CON emphasized RE, there was only a significant up-regulation of IL-15 in non-athletes. The level of IL-15 after CON RE in this group changed from 1.79 ± 0.6 to 2.16 ± 0.6 (P = 0.03, Figure 1A). Comparison of the serum IL-15 levels in athlete and non-athlete groups after each RE showed the highest IL-15 increase in athletes after ECC RE (0.73 ± 0.97 pg/mL).

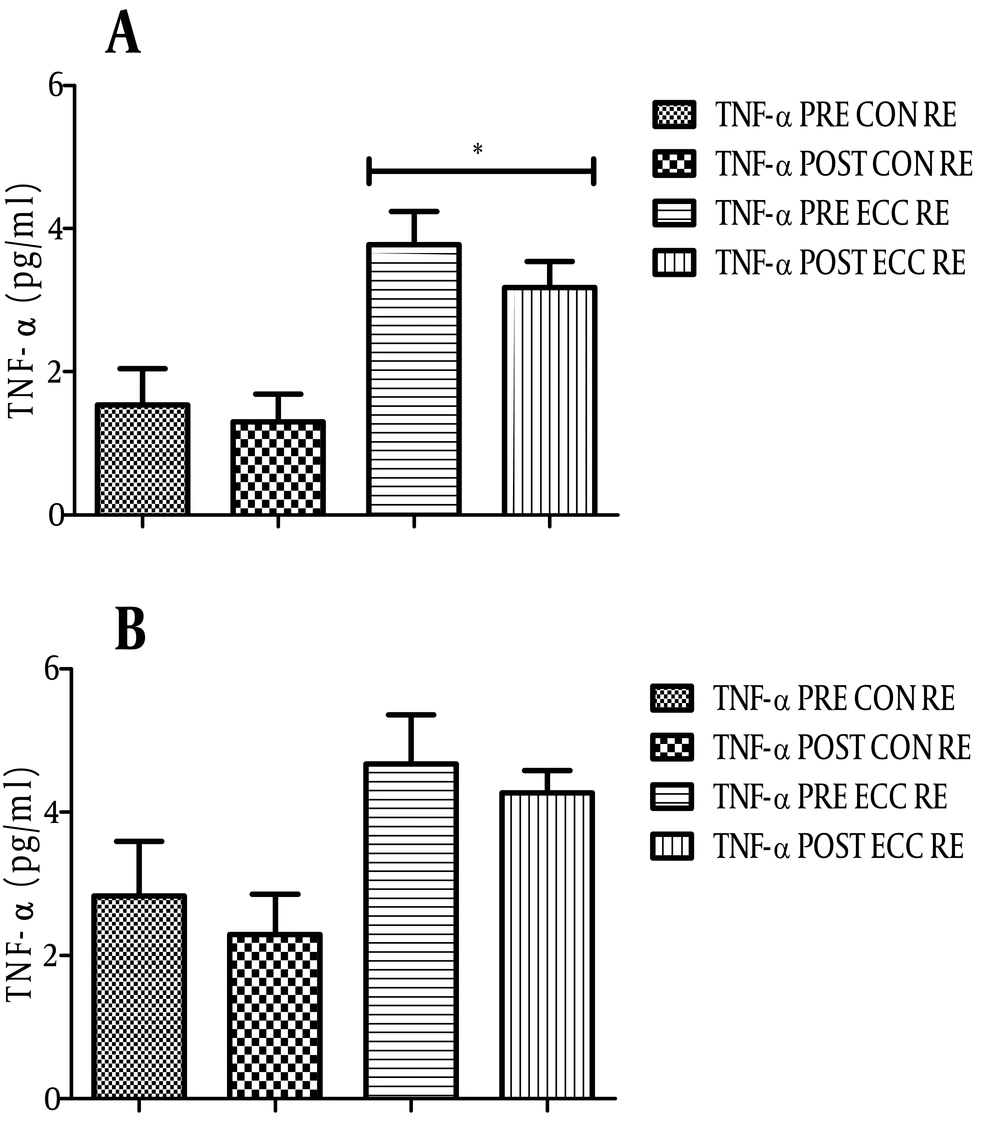

4.2. TNF-α Response to ECC and CON RE

We examined serum levels of TNF-α in subjects following ECC and CON RE (Figures 2A and B). TNF-α level in non-athletes significantly decreased after ECC RE. As shown in Figure 2, TNF-α levels in this group decreased from 3.78 ± 0.46 to 3.17 ± 0.36 pg/mL (P = 0.02). There were no significant detectable changes in TNF-α level after CON RE in non-athletes (1.53 ± 0.51 to 1.3 ± 0.4 pg/mL, P = 0.3). With respect to athletes, although the TNF-α level decreased from 2.83 ± 0.76 to 2.3 ± 0.57 pg/mL after CON RE and from 4.68 ± 0.68 to 4.27 ± 0.3 pg/mL after ECC, the result was not significant.

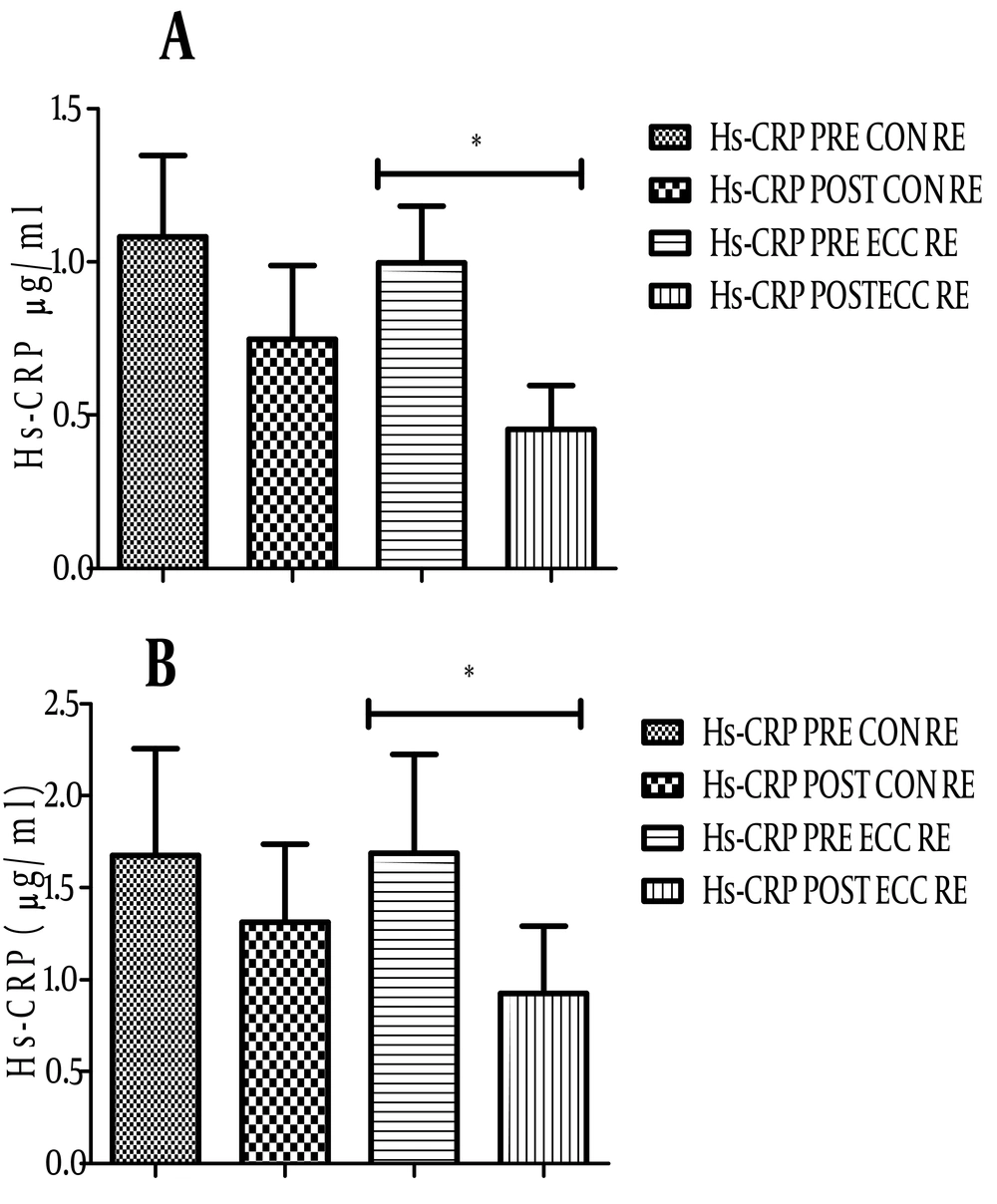

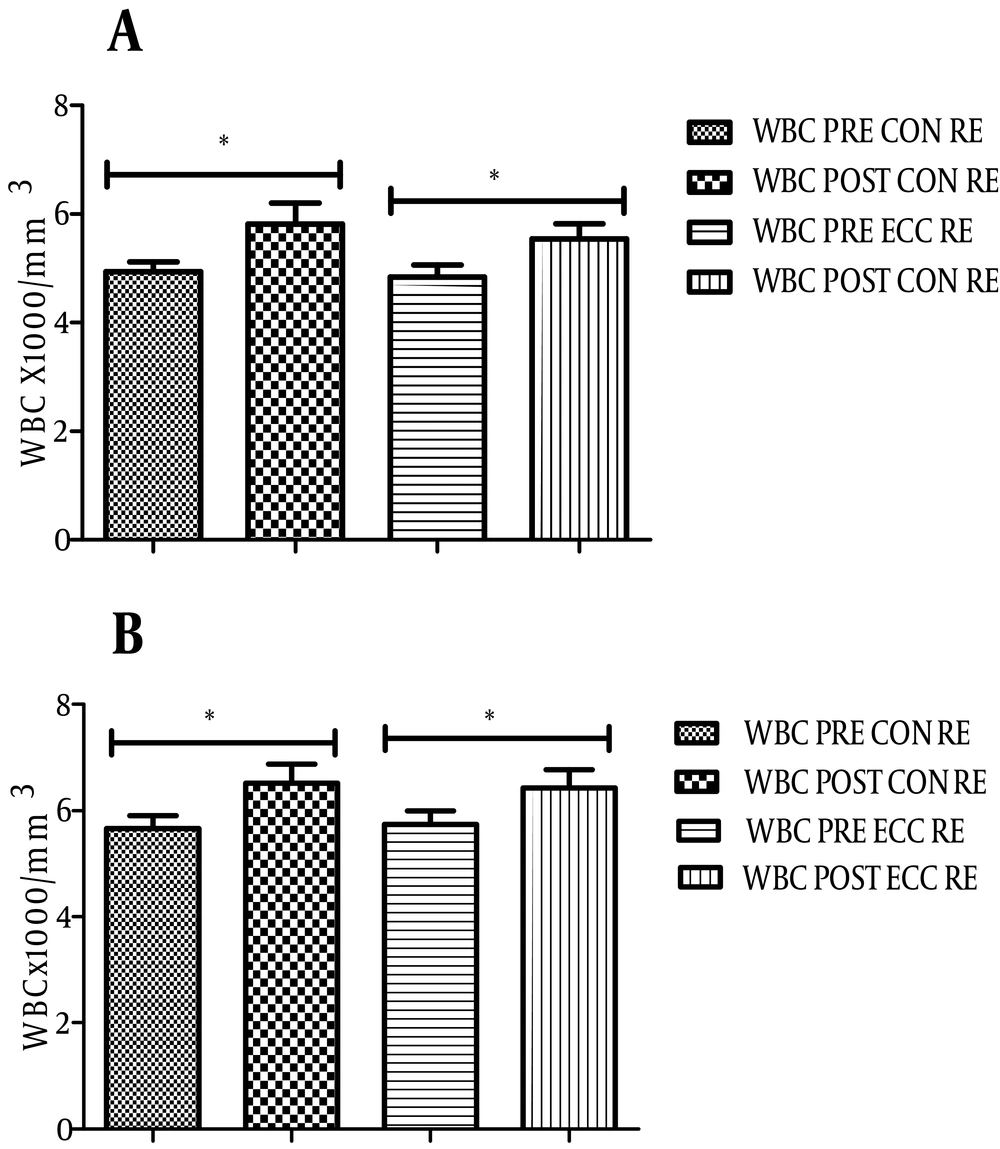

4.3. Changes in hs-CRP and WBC Levels After ECC and CON RE

As shown in Figure 3, the level of hs-CRP before and after ECC RE in athletes changed from 1.68 ± 2 to 0.92 ± 1.4 µg/mL (P = 0.01). ECC RE in non-athletes also significantly reduced the level of hs-CRP (0.99 ± 0.7 to 0.45 ± 0.5 µg/mL, P = 0.008, Figure 3A). Although the mean serum level of hs-CRP in both groups decreased after CON RE, it was not significant (Figure 3B). No significant correlation between changes in the level of hs-CRP and the cytokines was found. The number of WBCs as an index of systemic inflammation significantly increased after both RE protocols (Figures 4A and B, P < 0.05).

5. Discussion

In this study we found that IL-15 serum levels increased after one bout of ECC-emphasized RE in both athlete and non-athlete groups, however the changes were only significant following CON RE in the non-athlete group. We have observed the largest circulatory IL-15 changes in athletes after ECC RE. This could be justified by the concept that IL-15 is mainly secreted following major muscle ECC contractions that result in micro-tears rather than by CON contractions. This finding is in accordance with a previous study that has reported a 5% increase in IL-15 plasma levels after one bout of acute RE (10), but no changes after ten weeks of RE. The results of that study suggest that IL-15 release could be related to the exercise-induced inflammatory process resulting in secretion of cytokines and growth factors to repair damaged tissue and micro-tears.

Intensive ECC RE is widely used as a method for promoting and indirectly assessing skeletal muscle damage, which in turn induces an array of cytokine production to regulate the inflammatory process, including IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α (16, 17). Dieli-Conwright et al. have also reported a significant increase in IL-15 (18).

Dieli-Conwright et al. have reported a significant increase in IL-15 in eight postmenopausal women after one bout of acute single leg maximal isokinetic ECC RE, but they did not measure the changes in circulating levels of IL-15 (18). The increase in IL-15 serum level that has been observed in our study after CON RE in non-athletes and ECC RE in both groups may be explained by the sufficient intensity and load of this unusual mode of training in the induction of an inflammatory response that subsequently recruits IL-15 and other cytokines to blunt this response (19, 20). The ineffectiveness of endurance training on IL-15 was reported in some studies (12, 13), thus variation of exercise protocol could be assumed as a cause of contradictory results.

We have found an increase in the number of WBCs after both ECC and CON RE in subjects, which could show the occurrence of inflammation after the RE protocol. However, we did not find elevated hs-CRP, as an index of systemic inflammation. Rather, in contrast we have detected a significantly reduced level of this protein after ECC RE. Hs-CRP is an acute phase reactant that is markedly increased during inflammation and tissue injury (21). In a previous study performed by Malm et al. (16), a highly elevated CRP was reported 24 hours after incremental eccentric cycling exercise. In contrast, Milias et al. (22) did not find any significant changes in CRP levels at any of the time points after eccentric contractions. Production of CRP from hepatocytes is stimulated by increase in blood proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1 (23). On the other hand IL-15 and other anti-inflammatory cytokines can inhibit liver CRP production by direct blockage of TNF-α signaling (24). The significant decrease in hs-CRP that has been observed in both groups after ECC RE could be justified by reductions in the level of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. We found a general decrease in serum TNF-α after ECC and CON RE in both groups, though the difference was significant only in the non-athletes after ECC RE. This decreased TNF-α and hs-CRP levels along with the increased IL-15 level may be suggestive of a possible down-regulatory role of IL-15 on the inflammatory process that could be developed during RE, particularly amongst subjects with lower physical fitness levels or non-athletes. Whether this effect is a direct effect or other cytokines are also involved in this process needs more investigation.

The effects of exercise intensity on myokine release have been investigated in a few studies (25). Data from the Copenhagen Marathon race suggested a correlation between the intensity of exercise and increase in plasma myokines (26). Although low intensity exercise did not change IL-15 levels in previously published reports (11, 12), the intensive RE (either ECC or CON RE) in the current study and conventional RE in a study by Riechman et al. (10) have resulted in increased levels of circulating IL-15.

Our study and that by Riechman et al. (10) researched the effects seen with recruiting all major muscle groups within the body; however, other studies that showed no changes in levels of circulating IL-15 researched only isolated muscle groups (11-13). In addition, our exercise protocol and the protocol used by Riechman et al. (10) recruited more motor units as major skeletal muscles in RE, the results of which have shown greater inductive effects on the appearance of systemic cytokines in comparison with one (27) or two (11, 28) muscle group recruiting exercise protocols. The extent of muscle mass recruited during exercise might have a great impact on the circulating concentration of IL-15. This modulation has previously been reported with systemic IL-6 (29).

Overall, our results showed increased serum levels of IL-15 in response to whole body intensive CON and ECC emphasized RE in addition to its enhanced release into the circulation following ECC RE, particularly in athletes. This result differed from previous researches where isolated sections of the body (12) were involved and has indicated that this form of RE is a sufficient physiological stimulus for the up-regulation of IL-15 production. The increase in IL-15 and decrease in hs-CRP and TNF-α levels possibly has shown the potential anti-inflammatory effects of IL-15 may suggest the beneficial role of IL-15 in modulating some of the undesirable inflammatory effects of RE.