1. Background

The function of all organs and health status are dependent on the body water and electrolyte balance (1, 2). Water facilitates biochemical reactions within cells and tissues and is critical for maintaining the blood volume (3). Body water compartments contain electrolytes, which are essential for moving fluid between extracellular and intracellular space and for producing cell membrane potentials (4). One hour of moderate physical activity produces 0.5 to 1.5 L of sweat and considerable water loss occurs during several hours of vigorous exercise in a hot environment (4), which can lead to the loss of electrolytes such as sodium (5, 6). The loss of body fluid impairs thermoregulation, circulatory system and athletic performance (7, 8). Soccer is the most popular sport among the Iranian high school students. Hundreds of high school students in Iran participate in soccer training programs during summer holidays which last for three months. Soccer is a combination of aerobic and anaerobic activities, leading to high rates of metabolic heat production and may cause dehydration during hot summer days (9). We are unaware of any studies about dehydration in the Iranian young soccer players, but a recent study by Da Silva et al showed that mean sweat losses were approximately 2.5 L in young soccer players during a match played in the heat (31.0 ± 2.0°C) and the players replaced less than 50% of their sweat loss (10). Recent data indicated significant water deficit in young soccer players, when water or sport drinks were available, an indication of involuntary dehydration (11). It is well documented that dehydration reduces plasma volume (12) which in turn will lead to active muscles blood flow restrictions and core temperature rising, both of which compromise athletic performance and thermal regulation during physical activity under hot conditions (13). In general, water and electrolytes replenishment before, during and after exercise and precooling are approaches which have been used to prevent the athletic performance impairment and heat related injuries in a high ambient temperature. Water-immersion, cool water showering, the wearing of ice-cooling garments and cold air exposure are different methods of pre-cooling. Reduction of body temperature prior to a subsequent exercise bout under high temperature condition is the underlying rationale for all the methods.

In a study conducted by Cotter et al. it was shown that an ice vest with and without thigh cooling + cold air can increase endurance performance during 35 minutes cycling under warm conditions (33°C) (14). Booth et al. reported increased distance ran in 30 minutes by 304 m (+ 4%) in a warm humid environment (31.6°C, 60% rh) after water immersion (24°C) (15). Gonzalez-Alonso et al. demonstrated that, compared to the exercise capacity in the control trial, exercise capacity could be enhanced (~ 37%) by pre-cooling to an esophageal temperature of 35.9 ± 0.2°C and reduced (39%) by warming to a temperature of 38.2 ± 0.1°C (16). In another study, Schmidt and Bruck using an exhaustive cycling test found that precooling (cold air exposure) improved the exhaustion time (17). Generally, a number of studies have shown precooling to increase time to exhaustion and improve performance in running or cycling.

To date no studies have assessed the effects of precooling in Iranian young soccer players.

2. Objectives

Therefore the aim of this study was to examine the effect of precooling (cold water immersion) on exhaustion time, oral temperature and plasma volume in young soccer players during an incremental exhaustive test in warm conditions.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Subjects

Sixteen young male soccer players from two competitive teams volunteered to participate in this study. G power analysis for repeated measure revealed this sample size was adequate to detect a moderate effect size (18). All the subjects were informed of the procedures and signed an informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the university of Zanjan.

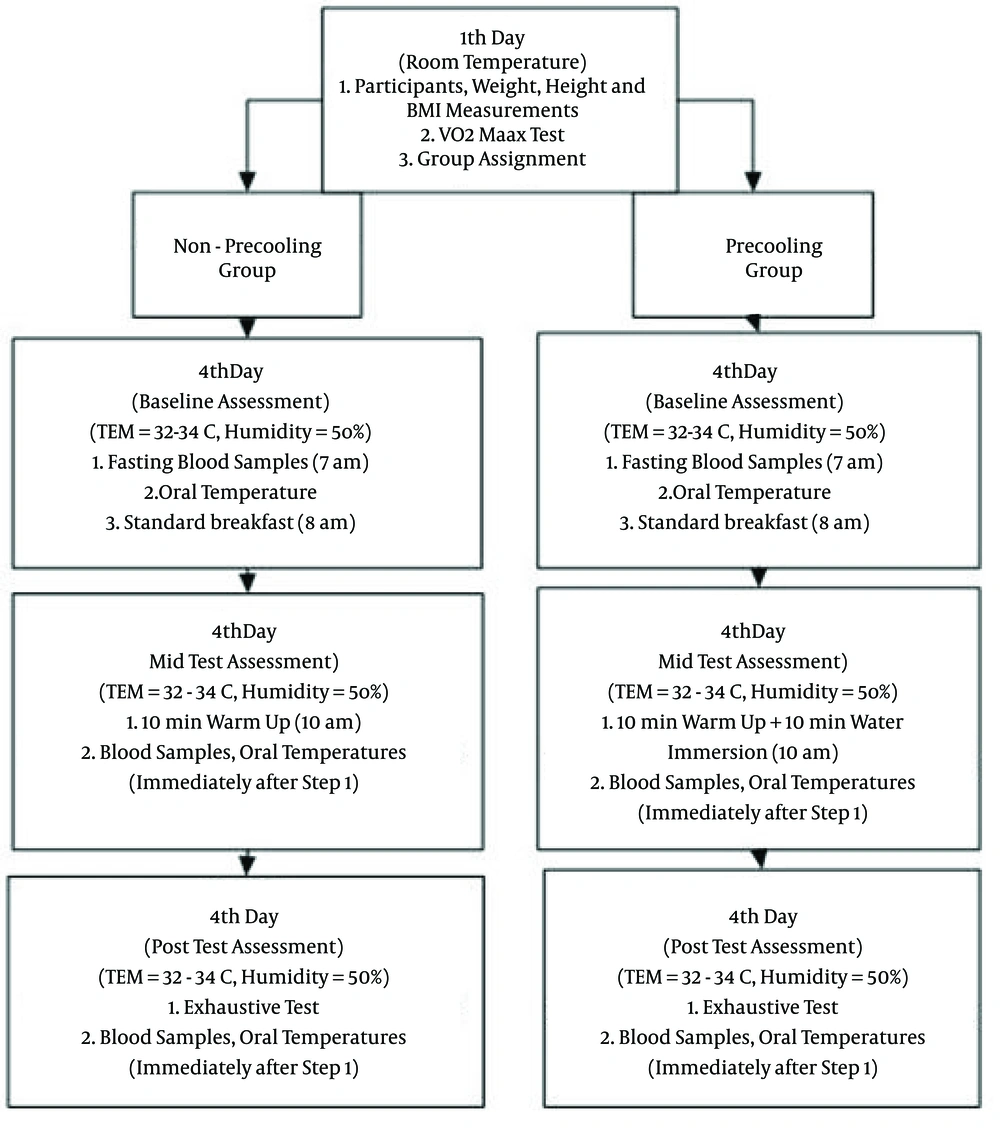

As shown in Figure 1, three days before the main trial subjects arrived at exercise physiology laboratory (room temperature) for baseline assessments. Height and weight were measured using stadiometer and electronic scale, respectively. Multistage maximal exercise test was conducted on a motorized treadmill (Cosmed, Italy) using Bruce protocol (19) and the following formula was used to estimate the VO2max (T = total time on treadmill in minutes):

VO2 max = 14.8 - (1.379 × T) + (0.451 × T²) - (0.012 × T³)

Then the subjects were divided into two equal groups based on age, height, weight and VO2max and were randomly assigned to precooling and non-precooling groups (Table 1). Three days after baseline assessments, subjects reported to the laboratory (tem = 32 - 34°C, humidity = 50%) following a 10 hour overnight fasting. The temperature in the laboratory was maintained at 32 - 34°C throughout the experiments.

| Variable | Group (N = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Precooling | Precooling | |

| Age, y | 16.1 ± 1.9 | 16.1 ± 1.1 |

| Height, cm | 170 ± 4.7 | 171.7 ± 6.4 |

| Weight, kg | 61.9 ± 12.3 | 63.56 ± 10.23 |

| VO2max, mL/kg/min | 50.69 ± 5.6 | 50.62 ± 6.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.33 ± 3.6 | 21.52 ± 3.3 |

3.2. Blood Samples Collection, Lactate and Plasma Volume Assessments

Blood samples were collected from the left antecubital vein as follows:

1) Pretest Fasting blood sample- 7 a.m.

2) Mid test sample- Both groups consumed standard breakfast at 8 a.m. Blood samples were drawn after 10 minutes of warm up( non-precooling group) or 10 minutes warm up + 10 minutes precooling (Precoling group) at 10 a.m.

3) Post test sample- immediately after exhaustive test.

The system K-4500 automated hematology analyzer was used to determine hemoglobin (mg/dL) and hematocrit (%) concentrations in the blood samples. Plasma lactate concentrations were measured using Kobas auto-analyzer and kits manufactured by Randox company of England.

In each of the subjects, the following equations were used to calculate the baseline, mid test and post test Plasma volume from the values of hematocrit (Hct%) hemoglobin (Hb mg/dL) (20).

BVA = BVB (HbB/HbA)

CVA = BVA (HctA)

PVA = BVA - CVA

PVB = BVB - CVB

PVA = BVA - CVA

Subscribes A and B refer to baseline and post treatment values, respectively and BVA is taken as 100. BV, CV and PV stand for the blood volume, red cells volume and plasma volume, respectively. Plasma lactate values were corrected based on plasma volume changes.

3.3. Oral Temperature

Oral temperatures were recorded pre (Baseline), mid (non-precooing group, at the end of warm-up; precooling group, at the end of warm up + precooling) and post test (immediately after exhaustive test) by Beurer FT 09 Digital Clinical Thermometer (Germany).

Non-precooling group conducted an exhaustive treadmill run test after a 10 minutes of warm up consist of light exercise and stretch training, while the same exhaustive test was done by precooling group after 10 minutes warm up + 10 minutes cold water immersion.

3.4. Precooling Maneuver

A small pool filled with water of 24°C and the water temperature was maintained between 22 - 24°C throughout immersion test. Participants in the precooling group were immersed up to the neck for 10 minutes. All the experiments were conducted at the laboratory temperature and humidity of 32 - 34°C and 50%, respectively.

3.5. Exhaustive Test

During exhaustive test, treadmill started at 7 km/h, the speed was increased by 1 km/h every 2 minutes until 10 km/h, and then the constant speed was maintained until volitional exhaustion.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test verified normal distributions of the data for exhaustive performance, plasma volume. If assumptions for normality were not met (oral temperature and plasma lactate), data were log-transformed before statistical analysis. The untransformed values are shown in the text, tables and figures. Precooling and non-precooling groups were as between subjects’ factor, and time (baseline, mid test and post test) was regarded as within subjects’ factor. A mixed repeated measures analysis of variance was used to assess the main effects and interaction effect of these factors on the dependent variables. If the significant time effect or group × time interaction effect were observed, then one way repeated measures with Bonferroni as post-hoc and independent samples t test were conducted for further analysis. Independent t test was used to compare the subjects’ characteristics and exhaustive performance. Research data were analyzed by SPSS-19. Partial eta-squared was used to assess the effect size and significant level was set P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

Both the study groups showed similar change in oral temperature from the pre to the post test [F (2, 28) = 11.87, P = 0.001, Partial Eta Squared = 0.4]. After exhaustive test oral temperature (post test) was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than the baseline and mid test in the precooling and non-precooling groups. There were no significant differences between precooling and non- precooling groups in the oral temperature measures [F (1, 14) = 1.63; P = 0.22, Partial Eta Squared =0.19; Table 2]. A significant time effect was observed for plasma lactate [F (2, 28) = 11.87, P = 0.001, Partial Eta Squared = 0.4]. In the both groups, plasma lactate increased form baseline to post test, but it was only in the non-precooling group that the post test plasma lactate was found significantly (P < 0.05) higher than the baseline and mid test (Table 2). No significant differences were observed between groups regarding plasma lactate [F (1, 14) = 0.05; P = 0.99; Partial Eta Squared = 0.025; Table 2]. Based on these findings, we can conclude that oral temperature and plasma lactate changes from baseline to post test showed a similar pattern in the precooling and non-precooling groups.

| Variable | Group (N = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Precooling | Non-Precooling | |

| Oral Temperature, ºC | ||

| Baseline | 36.16 ± 0.5 | 36.52 ± 0.23 |

| Mid test | 36.17 ± 0.5 | 36.71 ± 0.72 |

| Post test | 37.23 ± 0.6 A,B | 37.07 ± 0.44 A,B |

| Plasma lactate, mg/dL | ||

| Baseline | 15.88 ± 3.2 | 15.7 ± 2.1 |

| Mid test | 17.3 ± 6.5 | 14.81 ± 6.7 |

| Post test | 23.98 ± 10.20 | 23.25 ± 7.1 A,B |

| Plasma volume, mL/100 mL | ||

| Baseline | 56.02 ± 4.2 | 56.62 ± 2.2 |

| Mid test | 57.83 ± 1.3 | 56.05 ± 2.7 |

| Post test | 58.80 ± 1.3 | 54.04 ± 2.2B,c |

| Exhaustion time, min | 40.87 ± 12.9 | 34.87 ± 5.9 |

aBaseline (fasting state); mid test, immediately after warm up (non-precooling group) or warm up + precooling (precooling group); Post test, immediately after an exhaustive test.

bDifferent capital letters in superscript shows significant differences compared with baseline and mid test, respectively.

cSignificant difference compared with the post test in the precooling.

The plasma volume change, from the pre to the post test, was not similar in the precooling and non-precooling groups [F (2, 28) = 1.25; P = 0.3; Partial Eta Squared = 0.082; Table 2]. There was significant between groups difference in plasma volume measure [F (1, 14) = 3.74; P = 0.007; Partial Eta Squared = 0.41; Table 2]. Subsequent independent t test analysis revealed higher post test plasma volume in the precooling than in non-precooling group (P = 0.03; Table 2). This evidence suggesting that precooling can attenuate plasma volume decrement during exhaustive activity in the hot.

The exhaustion time was considerably higher in the precooling group (40.87 ± 12 minutes) than in the non- precooling group (34.87 ± 5.9 minutes), but did not reach a significant level (P = 0.24; Table 2).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of precooling ( water immersion) on exhaustive performance at environmental temperature of 32 - 34°C and humidity of 50%. Two groups of the young soccer players performed an exhaustive treadmill run test after warm up or warm up + precooling. No significant difference was found in the exhaustion time between the precooling and non-precooling groups. In contrast to our result, previous studies had reported endurance performance improvement after precooling in hot condition. Booth et al. and Marino et al. reported endurance performance ( distance run or cycle) improvement after water immersion (15, 21). Cold air exposure (as a precooling maneuver) was found to increase the work output during an exhaustive or endurance type test (21). The authors interpreted the results in light of reduced thermoregulatory strain (21), decreased reliance on anaerobic energy production (22) and attenuated plasma volume reduction (16) in precooled condition. Greater heat storage rate has been reported in precooling trail than in control trail (23), which allows greater margin for metabolic heat production. Booth et al observed deep body temperature increment immediately after precooling which significantly decreased at the commencement of the exercise (15). We found no significant change in the oral temperature immediately after precooling, and there was no significant between group difference in mid test oral temperature (Table 2). Based on these results, it can be said that the lack of significant difference in exhaustive performance between precooling and control trails might be due to the fact that precooling did not create any heat storage capacity prior to the exhaustive test. Ten minutes of water immersion was conducted in this study, compared with the 60 minutes in the other studies (24). It seems that the immersing duration was not high enough to create thermal gradient for heat dissipation.

In the present study, precooling attenuated the plasma volume decrement during exhaustive test in the heat condition. At the same time, non precooling group showed reduction in plasma volume, which lead to the significant between group differences following exhaustive test (Table 2). Given this result, it can be said that the amount of fluid loss as sweat was higher in the non-precooling than that of in the precooling. Reduced plasma volume in the non- precooling group following exercise in hot condition, that is characterized as hypovolemia (decrease in the volume of blood plasma) (25), is in line with similar other studies which found a decrease in plasma volume (26, 27). During exercise in the heat, active muscles’ blood flow must be maintained at a high level to supply oxygen and substrates, On the other hand, high blood flow to the skin must also be maintained to convert heat to the body surface, but hypovolumia can restrict these tissues blood flow (28, 29). It is well established that acute anemia induces increased lactate concentrations in animals during exercise (22), and there is strong evidence that the hypovolumia is responsible for the increase in heat storage and a decrease in heat loss during exercise (3). These effects can limit the exercise performance in the heat (1). Compared with the non-precooling trail, our precooling maneuver attenuated the plasma volume reduction, but could not induce any positive effects on plasma lactate and exhaustive performance, since no significant differences were found in the post test plasma lactate and exhaustive performance between the two groups (Table 2). In an earlier study, blood lactate was decreased despite an increase in endurance performance following precooling (30). It was speculated that decreased blood lactate following precooling might in part be associated with altered muscle metabolism due to the marked reduction in tissue temperature (30). We did not find any difference in the oral temperature between two groups following precooling. Oral cavity temperature is considered as a reliable index of core temperature when the thermometer is placed into the sublingual pocket, because the sublingual pocket is close to the sublingual artery and tracks changes in core body temperature (31). In this study, oral temperatures were recorded in the sublingual pocket. Therefore, we can probably say that the similar exhaustion time in two study groups was because of the fact that cold water immersing did not affect the core body temperature to induce positive metabolic change.

Significant difference in the plasma volume but similar body temperature and exhaustion time in the two study groups seems somewhat paradoxical. It is well documented that a body water deficit of greater than 2% of body weight marks the level of dehydration that can adversely affect thermoregulation and performance (32). Non-precooling group showed a body water loss of about 1% of body weight (data not presented) immediately after exhaustive test. It seems that the level of dehydration was not high enough to cause an adverse effect on exhaustive performance in the non-precooling group.

Compared to the non-precooling trail, the exhaustion time was not significantly but considerably higher in the precooling group (40.87 ± 12.9 minutes vs. 34.87 ± 5.9 minutes). Precooling elicited the similar thermoregulatory and metabolic responses as the non-precooling during exhaustive test. The limitation of this study was the fact that this research was not conducted with crossover design, therefore several confounders, as heat tolerance, heat acclimatization and running economy, independent of precooling could affect exhaustive performance.

Cold water immersion before an exhaustive test attenuates plasma volume decrement and cannot induce any ergogenic effect on exhaustive performance in the hot condition. The findings need to be verified in a crossover study using a soccer specific test and monitoring the true core temperature.