1. Background

Women’s basketball began in 1892 when Senda Berenson adapted James Naismith’s rules for women and introduced the game at Smith College (1). Since then, the game has spread internationally and been played all over the world, including Asia. Although international competitions of basketball have mostly been dominated by American and European teams, Asian women have shown better performances than Asian Men. To date, Asian women have won three medals at the Olympics (2) and five medals at FIBA world cups (3), whereas Asian men only have won one bronze medal at those competitions (4).

Recently, the author has investigated whether game-related statistics which discriminate winners from losers in men’s basketball differ between Asian and European competitions (5). The results show similar trends between Asian and European competitions, indicating that basic characteristics of men’s basketball games would be similar between the two regions and the difference in strength between Asian and European men’s basketball teams would be attributed to factors which would not be reflected in game-related statistics. Although exact factors were not identified in that study, anthropometric differences between Asian and European players can be speculated as one of the factors. For example, the average height of the players in the top eight teams of FIBA EuroBasket 2015 was 201 cm, whereas that of 2015 FIBA Asia Championship was 196 cm (6). However, anthropometric differences between Asian and European players exist in women as well. In fact, the average height of the players in the top eight teams of FIBA EuroBasket Women 2015 was 184 cm, whereas that of 2015 FIBA Asia Women’s Championship was 177 cm. Nevertheless, Asian women have shown better performances in international competitions than Asian men (2-4). Therefore, Asian women might have developed unique strategy and tactics which would be reflected in game-related statistics. However, studies on game-related statistics of women’s basketball are limited (7-9), and to the author’s knowledge, no studies on those of Asian women’s basketball have been published in major English-language journals in the field of sports science. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate whether game-related statistics which discriminate winners from losers in women’s basketball differ between Asian and European competitions.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and Variables

A total of 108 games from the 2011 (n = 36), 2013 (n = 36) and 2015 (n = 36) FIBA Asia Women’s Championships were analyzed for Asian competitions, and a total of 178 games from the 2011 (n = 54), 2013 (n = 54) and 2015 (n = 70) FIBA EuroBasket Women were analyzed for European competitions. Data were obtained from the official box scores of FIBA.

The following game-related statistics were analyzed: 2- and 3-point field goals (successful and unsuccessful), free throws (successful and unsuccessful), defensive and offensive rebounds, assists, steals, turnovers, blocks and fouls committed. These variables were normalized to 100 game ball possessions (5, 7, 10-12) in order to eliminate the effect of game rhythm. Game ball possessions were calculated as an average of team ball possessions of both teams (13). Team ball possessions (TBP) were calculated from field goal attempts (FGA), offensive rebounds (ORB), turnovers (TO) and free throw attempts (FTA) using the following equation (13):

TBP = FGA - ORB + TO + 0.4 × FTA

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The games were first classified into three types (balanced, unbalanced and very unbalanced) according to point differential by a k-means cluster analysis (5, 11, 14, 15). The difference in the proportion of game types between the two regions was analyzed by a chi-square test. After the analysis, very unbalanced games were eliminated from further analyses. The difference between winners and losers in each variable was analyzed by an independent t-test. A discriminant analysis was performed using R code ‘candis’ (16) and ‘geneig’ (17) to identify game-related statistics which discriminate winners from losers in each game type. An absolute value of a structural coefficient (SC) equal to or above 0.30 was considered relevant for the discrimination (5, 7, 10-12, 18). Statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.3.0 for Windows (19). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the game classification made by a k-means cluster analysis. The chi-square test was significant (P < 0.01), suggesting a difference in the proportion of game types between the two regions.

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of an independent t-test and a discriminant analysis. In balanced games, significant differences between winners and losers were found in successful 2-point field goals and assists in Asian competitions (P < 0.05), while those were found in most variables in European competitions (P < 0.05) except successful 3-point field goals, offensive rebounds and blocks. In unbalanced games, significant differences were observed in each variable of both regions (P < 0.05) except unsuccessful 3-point field goals (not significant in both regions), unsuccessful free throws (P < 0.05, only in Europe) and fouls committed (P < 0.05, only in Europe).

| Asia | Europe | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winners | Losers | SC | Winners | Losers | SC | |

| Successful 2-point field goalsb,c | 27.6 ± 7.1 | 24.2 ± 6.3 | 0.32 | 28.5 ± 5.8 | 24.4 ± 5.6 | -0.30 |

| Unsuccessful 2-point field goalsc | 35.2 ± 7.8 | 37.1 ± 9.4 | -0.14 | 33.8 ± 7.7 | 36.1 ± 8.0 | 0.12 |

| Successful 3-point field goals | 6.4 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 3.2 | 0.14 | 7.5 ± 3.5 | 7.3 ± 3.2 | -0.01 |

| Unsuccessful 3-point field goalsc | 15.5 ± 6.9 | 16.2 ± 7.3 | -0.06 | 14.8 ± 5.7 | 16.7 ± 6.1 | 0.13 |

| Successful free throwsc | 14.1 ± 5.8 | 12.6 ± 6.9 | 0.15 | 19.5 ± 7.9 | 16.0 ± 6.4 | -0.19 |

| Unsuccessful free throwsc | 7.6 ± 3.9 | 7.4 ± 4.5 | 0.03 | 6.7 ± 3.8 | 5.6 ± 3.5 | -0.11 |

| Defensive reboundsc | 30.5 ± 10.6 | 29.2 ± 10.2 | 0.08 | 38.4 ± 6.3 | 33.8 ± 4.7 | -0.34 |

| Offensive rebounds | 13.4 ± 7.1 | 13.1 ± 6.2 | 0.03 | 16.6 ± 6.1 | 16.0 ± 5.5 | -0.04 |

| Assistsb,c | 16.8 ± 4.2 | 13.5 ± 4.5 | 0.47 | 21.0 ± 6.0 | 18.2 ± 4.8 | -0.22 |

| Stealsc | 10.3 ± 6.1 | 8.4 ± 4.3 | 0.21 | 10.7 ± 4.2 | 8.8 ± 3.8 | -0.19 |

| Turnoversc | 19.8 ± 6.3 | 22.1 ± 6.6 | -0.22 | 21.4 ± 5.3 | 22.9 ± 5.4 | 0.11 |

| Blocks | 3.4 ± 2.3 | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 0.05 | 3.5 ± 2.7 | 3.0 ± 2.5 | -0.08 |

| Foulsc | 20.9 ± 6.3 | 21.9 ± 6.0 | -0.10 | 27.0 ± 5.4 | 29.6 ± 5.4 | 0.20 |

| Eigenvalue | 0.66 | 1.49 | ||||

| Wilks' Lambda | 0.60 | 0.40 | ||||

| Chi-square | 49.4 | 244.0 | ||||

| P Value | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | ||||

| Canonical correlation | 0.63 | 0.77 | ||||

| Reclassification (%) | 75 | 90 | ||||

Abbreviation: SC, structural coefficient.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bA significant difference exists between winners and losers in Asian games (P < 0.05).

cA significant difference exists between winners and losers in European games (P < 0.05).

| Asia | Europe | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winners | Losers | SC | Winners | Losers | SC | |

| Successful 2-point field goals b,c | 30.4 ± 6.7 | 19.0 ± 5.3 | -0.44 | 31.4 ± 6.1 | 22.8 ± 3.7 | -0.35 |

| Unsuccessful 2-point field goalsb,c | 34.3 ± 7.2 | 39.2 ± 10.2 | 0.13 | 34.2 ± 7.1 | 40.1 ± 8.1 | 0.16 |

| Successful 3-point field goals b,c | 8.8 ± 5.0 | 5.5 ± 2.9 | -0.19 | 8.0 ± 4.4 | 5.1 ± 2.9 | -0.16 |

| Unsuccessful 3-point field goals | 17.5 ± 7.0 | 15.7 ± 6.3 | -0.06 | 14.4 ± 6.2 | 16.6 ± 6.4 | 0.07 |

| Successful free throwsb,c | 14.0 ± 6.7 | 11.4 ± 5.3 | -0.10 | 18.1 ± 7.2 | 13.0 ± 6.4 | -0.15 |

| Unsuccessful free throwsb | 7.6 ± 5.0 | 6.8 ± 4.2 | -0.04 | 6.8 ± 4.3 | 4.8 ± 3.4 | -0.11 |

| Defensive reboundsb,c | 33.1 ± 9.1 | 28.2 ± 8.9 | -0.13 | 43.2 ± 7.0 | 32.3 ± 6.7 | -0.32 |

| Offensive reboundsb,c | 15.2 ± 7.5 | 11.8 ± 8.3 | -0.10 | 18.4 ± 5.7 | 14.2 ± 5.7 | -0.15 |

| Assistsb,c | 20.1 ± 7.6 | 9.1 ± 4.3 | -0.41 | 25.2 ± 6.6 | 15.0 ± 4.6 | -0.37 |

| Stealsb,c | 11.6 ± 6.4 | 7.4 ± 3.4 | -0.19 | 12.0 ± 4.0 | 9.6 ± 4.8 | -0.11 |

| Turnoversb,c | 16.9 ± 5.0 | 23.8 ± 7.5 | 0.25 | 20.1 ± 6.0 | 22.8 ± 5.6 | 0.10 |

| Blocksb,c | 3.6 ± 3.0 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | -0.15 | 4.7 ± 3.0 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | -0.16 |

| Foulsc | 19.1 ± 6.3 | 20.5 ± 6.3 | 0.05 | 24.2 ± 5.2 | 27.6 ± 6.6 | 0.12 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.71 | 6.18 | ||||

| Wilks’ Lambda | 0.18 | 0.14 | ||||

| Chi-square | 131.6 | 129.2 | ||||

| P Value | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | ||||

| Canonical correlation | 0.91 | 0.93 | ||||

| Reclassification (%) | 99 | 99 | ||||

Abbreviation: SC, structural coefficient.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bA significant difference exists between winners and losers in Asian games (P < 0.05).

cA significant difference exists between winners and losers in European games (P < 0.05).

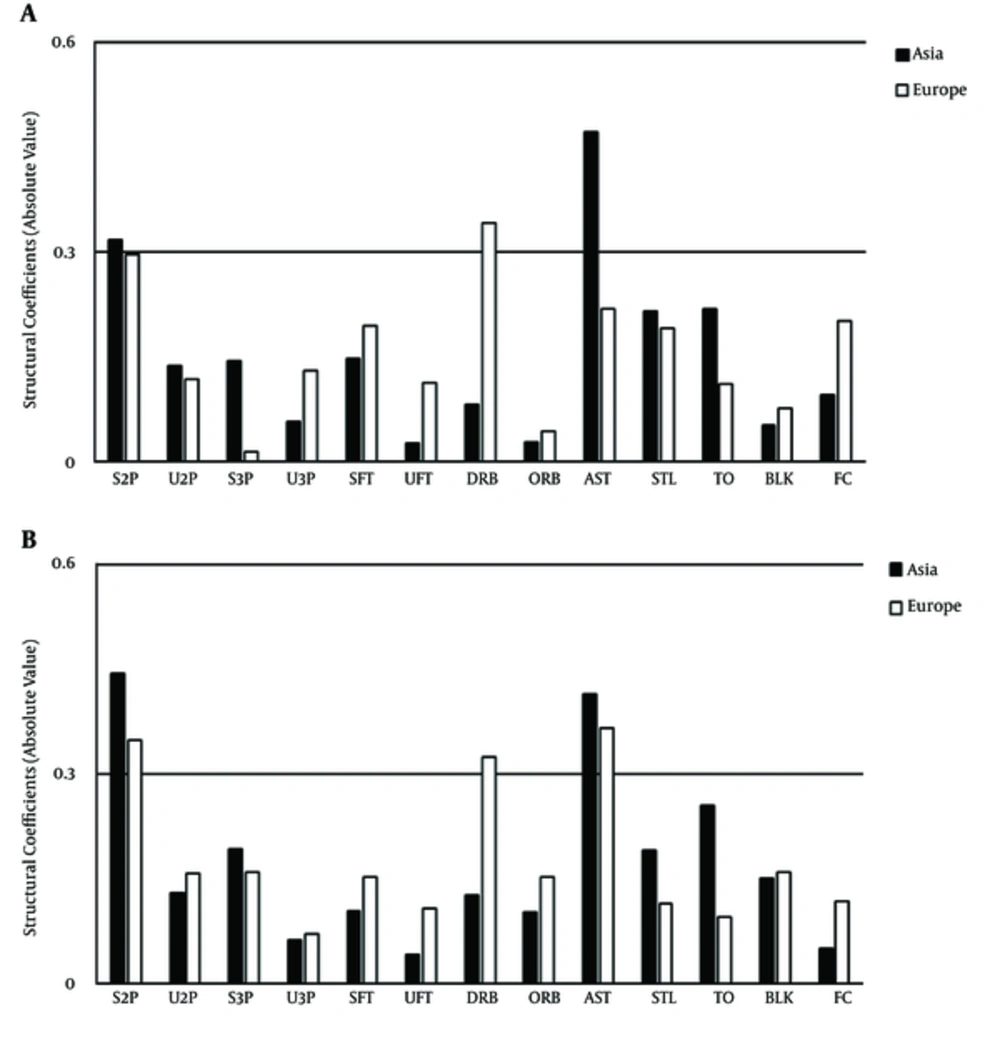

Absolute values of SC are presented in Figure 1. Successful 2-point field goals discriminated winners from losers independent of the region or game type (|SC| ≥ 0.30). Assists discriminated winners from losers (|SC| ≥ 0.30) except for balanced games in Europe (|SC| = 0.22). Defensive rebounds discriminated winners from losers only in Europe (|SC| ≥ 0.30).

S2P,successful 2-point field goals; U2P, unsuccessful 2-point field goals; S3P, successful 3-point field goals; U3P, unsuccessful 3-point field goals; SFT, successful free throws; UFT, unsuccessful free throws; DRB, defensive rebounds; ORB, offensive rebounds; AST, assists; STL, steals; TO, turnovers;BLK, blocks; FC, fouls committed.

4. Discussion

The most notable finding of this study was that defensive rebounds discriminated winners from losers in European but not in Asian competitions. A number of studies have shown that defensive rebounds discriminate winners from losers in a certain league or championship (5, 7, 10, 15). For example, in the author’s previous study on Asian and European men’s championships (5), defensive rebounds discriminate winners from losers independent of the region or game type. Although studies on women’s basketball are scarce, Gomez et al. (7) have shown that defensive rebounds discriminate winners from losers in the Spanish women’s league. In contrast, however, discriminating power of defensive rebounds in Asian women’s competitions was relatively weak either in balanced (|SC| = 0.08) or in unbalanced (|SC| = 0.13) games.

The number of defensive rebounds is correlated to field goal percentage, because an opportunity for getting a defensive rebound is caused by an unsuccessful shot of the opposing team (20). Oliver (20) has demonstrated that defensive rebounds become less effective on the outcome of a game in which field goal percentage is about the same for two teams. In fact, the difference in the average number of unsuccessful field goals between winners and losers in Asian competitions was smaller than that in European competitions. In addition, although the absolute value of SC did not exceed 0.30, the value in turnovers was relatively large in Asian competitions compared to that of European competitions (balanced, 0.22 vs. 0.11; unbalanced, 0.25 vs. 0.10). From these results, it can be assumed that losers in Asian games tended to lose ball possession before attempting field goals, and thus reducing opportunities for winners to get defensive rebounds.

The above-mentioned difference between Asian and European women’s competitions was similarly observed between under-16 (U16) and under-18 (U18) men’s competitions (11, 21): turnovers (|SC| = 0.47) but not defensive rebounds (|SC| = 0.01) discriminated winners from losers in U16 games with point differences equal to or below nine points (11), whereas defensive rebounds (|SC| = 0.50) but not turnovers (|SC| = 0.13) did so in U18 games with point differences equal to or below 12 points (21). Lorenzo et al. (11) suggested that U16 players tended to make unforced or forced errors and had difficulty in maintaining ball possessions, pointing out that the average number of ball possessions in U16 games was greater than U18 games (U16, 78.2; U18, 73.4). The average numbers of ball possessions in Asian and European women’s games (Asia, 78.3; Europe, 71.1) were comparable to those in U16 and U18 games. Therefore, Asian women’s games might have similar characteristics to U16 men’s games. Improving individual skills and/or team tactics to maintain possessions and finishing each possession with a field goal attempt would make Asian teams stronger. It should be noted, however, that even if this assumption is correct, it does not necessarily mean that Asian games are less-developed compared to European games. As anthropometric differences (e.g. height) exist between Asian and European players, the optimal strategy and tactics might also differ. Establishing the strategy and tactics which are suitable to their characteristics might be a reason why Asian women have shown better performances in international competitions compared to Asian men.

This study is not without limitations. Although a discriminant analysis of game-related statistics has been an established method and widely performed in basketball research, it is not enough to fully investigate the game. On the other hand, several recent studies have focused on specific elements of the game such as shot (22), screen (23-25), fast break (26), substitution (27) and foul (28, 29). Conducting those types of studies would compensate the limitation and help to fully understand the characteristics of the game.

4.1. Conclusions

This study showed that defensive rebounds discriminated winners from losers in European but not in Asian women’s basketball championships. It was suggested that losers in Asian games tended to lose ball possession before attempting field goals, and thus reducing opportunities for winners to get defensive rebounds.