1. Background

Preterm labor (PL) is defined as pregnancy termination before the end of the 37th week of gestational age (GA). It occurs in 8% to 10% of all pregnancies and 5% of the Iranian population (1). Preterm labor is one of the leading causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide (2-4). Acute and late complications, including the need for resuscitation, lower Apgar score, and visual problems, are noticeably higher in premature neonates (5).

Different factors can result in PL, including a history of PL, lower genital system infection, multiparty, low socioeconomic status, and smoking (6, 7). Since the insufficient level of vitamin D during pregnancy is related to a higher risk for some pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes (GDM), and small for gestational age (SGA) (8-11), it is hypothesized that there may be an association between serum vitamin D and preterm labor.

There is no effective and safe treatment for PL, and it seems the best treatment for this complication is preventive strategies (12). On the other hand, there are inconsistent studies about the association between serum vitamin D concentration and preterm labor.

2. Objectives

This study was designed to compare the vitamin D level of pregnant women with PL and the control group.

3. Methods

This case-control study was conducted on 156 pregnant women (52 cases and 104 controls) in Ali Ibn Abitaleb Hospital, Zahedan, Iran, in 2018. A convenience sampling method was utilized. Using the proportion formula, we calculated the sample size based on the data reported in Baczynska-Strzecha and Kalinka study (10). The total sample size was 156, but the control group's sample size was twice that of the case group to compensate for the limited number of cases and improve study power.

Singleton pregnant women older than 18 years, whose gestational ages at delivery were lower than 37 weeks (according to first-trimester ultrasound), were included in the case group. Besides, singleton pregnant women older than 18 years with term delivery (≥ 37 weeks' GA at delivery) were enrolled in the control group. The exclusion criteria for both case and control groups included pregnant women with underlying diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cervical insufficiency, drug consumption affecting vitamin D absorption, smoking, alcohol drinking, and withdrawal from the study.

Blood samples were drawn at delivery without fasting to determine vitamin D. Vitamin D was measured by the enzyme immunoassay method. As we checked vitamin D levels at delivery, the treatment of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency was initiated after pregnancy. Hence, the treatment of the patients did not compromise our data.

We gathered data including age, obstetrics history, body mass index (BMI), GA at delivery, and serum vitamin D level. The data were analyzed with SPSS version 24 software. Mean ± standard deviation and independent t test were applied for continuous variables, and percentages and the chi-square test were for categorical variables. The statistically significant level was considered less than 0.05.

4. Results

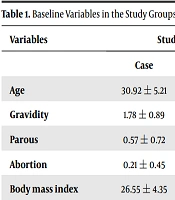

The age was 30.92 ± 5.21 and 29.39 ± 4.86 years in the case and control groups, respectively. The BMI was 26.55 ± 4.35 and 25.18 ± 4.55 kg/m2 in the case and control groups, respectively. There were no significant (P-value > 0.05) differences between the two groups in baseline variables (Table 1).

| Variables | Study Group | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | ||

| Age | 30.92 ± 5.21 | 29.39 ± 4.86 | 0.073 |

| Gravidity | 1.78 ± 0.89 | 1.76 ± 0.81 | 0.893 |

| Parous | 0.57 ± 0.72 | 0.53 ± 0.62 | 0.730 |

| Abortion | 0.21 ± 0.45 | 0.24 ± 0.51 | 0.731 |

| Body mass index | 26.55 ± 4.35 | 25.18 ± 4.55 | 0.074 |

Furthermore, vitamin D supplement consumption (P-value = 0.128), sun exposure time (P-value = 0.304), history of admission in pregnancy (P-value = 0.608), and history of vaginal infection (P-value = 0.100) were not significantly different between two groups.

The average vitamin D levels in pregnant women with and without PL were 30.88 and 31.93 ng/mL, with no significant difference (P-value = 0.591). The babies' weight was significantly (P-value > 0.001) higher in the control group than in PL women (3338.75 ± 466.16 vs. 2655.76 ± 393.36 g).

5. Discussion

Vitamin D has different and important roles during pregnancy. Evidence (13) shows insufficient vitamin D is associated with gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and low birth weight. However, the association between vitamin D level and incidence of PL has not been well understood. This study evaluated this possible association.

Our findings showed no significant difference in the frequency of vitamin D insufficiency subgroups between the two study groups. In line with our study, a former study (14) showed that mean vitamin D was not significantly different between women with PROM and the control group. However, Bodnar et al. (15) and Shibata et al. (16) showed that the deficient level of vitamin D (< 10 ng/mL) caused preterm labor. Bodnar et al.'s study (15) was conducted on twin pregnancies. Our study showed that both groups had a mean vitamin D level in normal ranges (≥ 30 ng/mL). It might be due to an increase in pregnant women's knowledge about vitamin D's important role and daily consumption of vitamin D supplements.

Preterm labor is affected by different known or unknown factors (17, 18); for instance, women in the low and high range of reproductive ages are more susceptible to PL (19, 20). On the other hand, preventive strategies are more effective in decreasing PL incidence and its short- and long-term complications. Hence, vitamin D supplementation in pregnant women to counter vitamin D deficiency seems rational (21).

Despite the strengths of this study, such as having a control group and using the same laboratory for vitamin D measurements, there were some limitations, including the low sample size, retrospective nature of the study, and broad inclusion criteria. Future research is suggested with more sample size of pregnant women with unknown PROM.

5.1. Conclusions

Although this study showed no significant association between vitamin D levels and PL, abnormal vitamin D levels may be related to PL in pregnant women with other comorbidities or risk factors such as preeclampsia and high BMI.