1. Background

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is recognized as one of the causes of nosocomial infections (1). Nowadays, due to the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance, E. coli is recognized as one of the most resistant bacteria to broad-spectrum antibiotics (2). Also, beta-lactam antibiotics are the most important drugs that are commonly used worldwide to treat bacterial infections (3). Resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics is created by different mechanisms, such as beta-lactamase enzymes, such as expanded spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), efflux pumps, and porins (4). ESBL-producing bacteria are associated with several crucial health problems in the world (5). Currently, more than 300 ESBLs have been identified, forming after mutation of beta-lactamase enzymes (6). The main encoding genes of the ESBLs are CTX-M, TEM, and SHV groups of Amber molecular class (7).

ESBL-producing bacteria are mainly found in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) of the hospitals (8) Also, they are resistant to other antibiotic groups (3). Therefore, suitable drugs to treat the bacteria will be very limited, which is the main concern regarding the spread of ESBL strains (9). Identification of this bacteria and increasing knowledge about its presence in a geographical location are effective in the proper and effective use of suitable antibiotics in the region (10). Accordingly, it is the responsibility of health and microbiological officials of each region to monitor and track the growth rate of bacteria resistant constantly, especially ESBLs strains, to control and prevent drug-resistant outbreaks (11). Also, the information on the growth and spread rate of these enzymes helps in the treatment and prevention of infections caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (12).

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of antibiotic resistance and ESBL in E. coli isolates of the urine samples taken from the patients in Qom hospitals using the phenotypic and genotypic methods.

3. Methods

3.1. Separation of the Isolates

As stated earlier, during three months (October to December 2014), 200 samples suspected of E. coli were taken from the urinary tract infection (UTI) of the hospitalized patients in ICUs of three different hospitals in Qom, Iran, and then evaluated. Microbiological standard tests, such as gram stain, IMViC, oxidase, catalase, and fermentation/oxidation tests were used to identify the isolates (13) (all strains were Gram-negative bacilli, indol positive, citrate negative, Voges-Proskauer (VP) negative, and methyl red (MR) positive).

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern

To identify the antibiotic susceptibility pattern, the disk diffusion agar test (Kirby Bauer method) (14) was performed using 17 different antibiotic types (Mast, UK). These antibiotic disks included ampicillin (30 µg), Piperacillin (30 µg), cefuroxime (30 µg), imipenem (30 µg), nitrofurantoin (30 µg), amikacin (30μg), aztreonam (30 µg), carboncillin (30 µg), Cefepime (30 µg), Ceftriaxone (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (30 µg), Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (30 µg), Gentamicin (30 µg), Ofloxacin (30 µg), Nalidixic acid (30 µg), Cefotaxime (30 µg), and Ceftazidime (30 µg) in terms of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) procedures (14).

3.3. ESBLs-Producing Isolates by Combination Disc Method

Combined carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) testing was applied to screen the ESBL-producing E. coli. The CDT phenotypic test was performed by the disks of ceftazidime (30 µg) and cefotaxime (30 µg) alone and in combination with clavulanic acid (10 μg) in Muller Hinton Agar. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, an increase in zone size of ≥ 5 mm was considered as a positive ESBL isolate. In the present study, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 (prepared by the Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran) was used as positive control (15).

3.4. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification for TEM, SHV, and CTX-M Genes

DNA extraction was performed using the boiling method. Then, the quality and quantity of all the extracted DNAs were evaluated by the spectrophotometer and gel electrophoresis. The presence of TEM, CTX-M, and SHV were studied using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (16). The ingredients of the PCR mixture were as follows for 25 mL PCR reaction: 50 mm of Tris-HCL, 50 mM of (pH = 8) KCL, 15 mm of MgCl2, 0.2 mm dNTP mix, 20 pM of each primer (Table 1), and 5 mg of the extracted DNA. PCR was performed at the temperature conditions shown in Table 2. The PCRs products were exposed to electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel.

| Genes | Primer Sequences (5’ → 3’) | Temperature, °C | Length, bp | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaSHV | Forward: -GCTTTCCCATGATGAGCACC | 60 | 292 | Primers were designed by the authors |

| Reverse: -AGGCGGGTGACGTTGTCGC | 61 | |||

| blaTEM | Forward: -GGTGAAAGTAAAAGATGCTGAAG | 59 | 559 | |

| Reverse: -AACTTTATCCGCCTCCATC | 60 | |||

| blaCTX-M | Forward: -GCGGAAAAGCACGTCAAT GGG | 62 | 427 | |

| Reverse: -GCCAGATCACCGCGATATC | 61 |

Primers Used for Amplification of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M Genes in the Present Study

| Steps | Temperature, °C | Time, min | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHV | CTX-M | TEM | SHV | CTX-M | TEM | |

| Initial denaturation | 95 | 95 | 95 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Denaturation | 95 | 95 | 95 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Annealing | 57 | 60 | 55 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Extension | 72 | 72 | 72 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Final extension | 72 | 72 | 72 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Cycle number | 35 Cycle | |||||

Polymerase Chain Reaction Conditions for Amplification of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M Genes in the Present Study

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The results of antibiotic susceptibility pattern, a confirmatory test for ESBL production, and the existence of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes were analyzed using SPSS software (version 16) and Fisher’s exact test.

4. Results

The experiment was performed on 200 E. coli isolates taken from the urine samples of cases in the ICU in Qom hospitals, of whom 152 (76%), 25 (12.5%), and 23 (11.5%) patients were women, men, and infants, respectively. The result of the antibiotic sensitivity test is shown in Table 3. According to the results, most of the isolates (192, 96%) were resistant to ampicillin and the least resistance was found to Nitrofurantoin (39, 19.5%). Based on the results of the combined disk tests, 156 samples (78%) were producers of ESBLs, and 44 strains (22%) were non-ESBLs producers.

| Antibiotic | Resistant | Intermediate | Sensitive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbenicillin | 90 (45) | 11 (5.5) | 99 (49.5) |

| Piperacillin | 175 (87.5) | 21 (10.5) | 4 (2) |

| Ofloxacin | 69 (34.5) | 19 (9. 5) | 112 (56) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 39 (19.5) | 110 (55) | 51 (25.5) |

| Amikacin | 57 (28.5) | 71 (35.5) | 72 (36) |

| Ceftriaxone | 90 (45) | 62 (31) | 48 (24) |

| Ampicillin | 192 (96) | 8 (4) | - |

| Imipenem | 77 (38.5) | 43 (21.5) | 80 (40) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 72 (36) | 27 (13.5) | 101 (50.5) |

| Aztreonam | 182 (91) | 16 (8) | 2 (1) |

| Cefepime | 83 (41.5) | 52 (26) | 65 (32.5) |

| Gentamicin | 55 (27.5) | 41 (20.5) | 104 (52) |

| Nalidixic acid | 133 (66.5) | 23 (11.5) | 44 (22) |

| Co-trimoxazole | 137 (38.5) | 4 (2) | 59 (29.5) |

| Cefuroxime | 180 (90.5) | 19 (9. 5) | 59 (29.5) |

| Cefotaxime | 160 (80) | 31 (15.5) | 9 (4.5) |

| Ceftazidime | 94 (47) | 60 (30) | 46 (23) |

Antibiotics Sensitivity Pattern of the Escherichia coli Strainsa

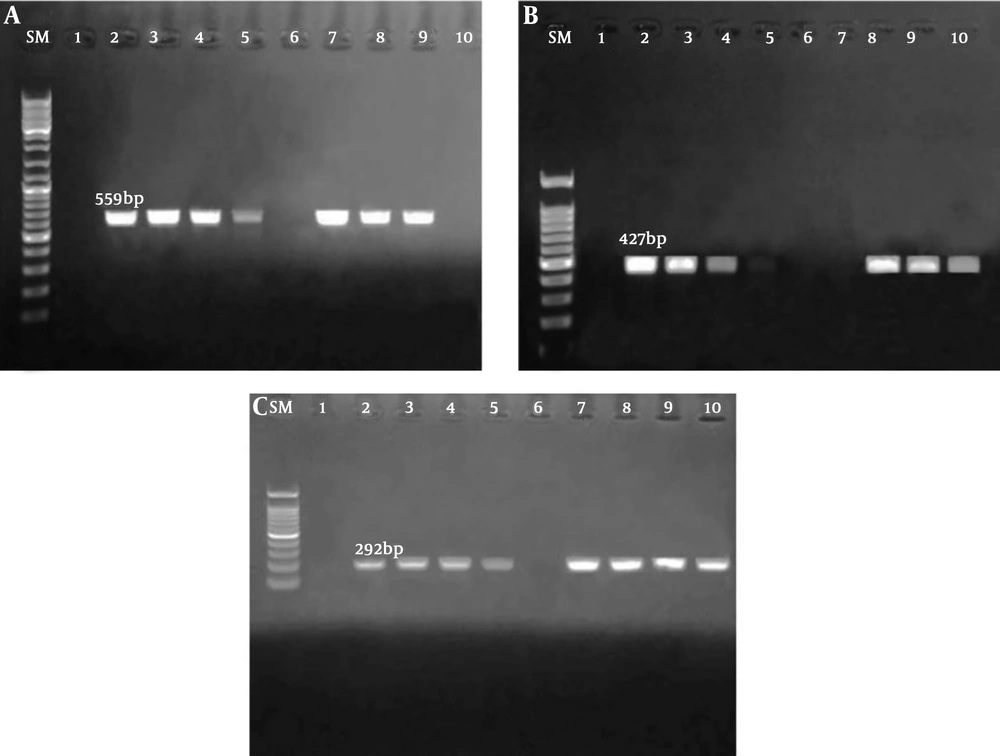

According to the result of PCR assay, 123 (61.5%), 76 (38%), and 90 (45%) Escherichia coli strains posed blaTEM, blaCTX-M, and blaSHV genes, respectively (Figure 1).

A, SM: Marker size (100 bp), lane 1: negative control, lane 2: positive control, lanes 3, 4, and 7 - 9: Escherichia coli strains blaTEM positive, and lane 6 and 10: negative E. coli strains for blaTEM; B, SM: marker size (100 bp), lane 1: negative control, lane 2: positive control, lanes 3, 4, 5, and 7 - 10: positive E. coli strains for blaSHV, and lane 6: negative E. coli strain for blaSHV; C, SM: marker size (100 bp), lane 1: negative control, lane 2: positive control, lanes 3, 4, and 7 - 9: positive E. coli strains for blaCTX-M, and lane 6: negative E. coli strains for blaCTX-M.

5. Discussion

Over one million people hospitalized for different medical conditions and during a hospital stay have been infected with nosocomial infections. Nosocomial infection is the most common cause of complications and problems for medical personnel, patients, and all hospitals in Iran (17).

The risk of nosocomial infections has been reported to be from at least 0.27 (0%) to more than 6/27 (22.2%) between 2010 and 2015, respectively (18). These infections can easily be transmitted among patients and their visitors, hospital personnel, and those with direct contact with the hospital environment (1). The highest number of nosocomial infections occurs in the ICU, therefore, it is known as one of the most important responsibilities of lab technicians to identify and control these infections (9). Additionally, E. coli is the most evident and frequent organism, which is also a critical pathogen for UTI (19).

In our investigation, the highest and lowest resistances were found to ampicillin and nitrofurantoin, respectively. However, various resistant rates have been reported from different parts of the world, mostly due to the different patterns of antibiotic use. Rajabnia et al. (19) in Iran indicated that cefotaxime and meropenem had the highest and lowest resistance rates, whereas Jena in India (2017) reported ceftazidime and colistin with the highest and lowest resistance rates (19, 20).

Previous studies conducted in India, Poland, Africa, Iraq, Iran, and other countries showed different rates of antibiotic resistance in E. coli strains (20-24).

We also found a high rate of blaTEM (61.5%), blaCTX-M (45%), and blaSHV (38%) genes in clinical strains isolated from the patients with UTI admitted to the ICU. However, blaSHV was less than the other two types of genes. Moreover, another study conducted in India reported that 93.47%, 82.60%, and 4.34% of blaTEM, blaCTX-M, and blaSHV genes in E. coli were isolated from adult patients with UTI, respectively (20). Polse et al. (23) in a study performed in Iraq indicated that E. coli strains isolated from UTI included 87.2%, 54.5%, and 21.8% of blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV genes, respectively. In contrast, a recent study by Nojoomi and Ghasemian (25) in 2016 in Iran the prevalence of blaCTX-M-1, blaSHV and blaTEM was 77.4% (n = 86), 47.4% (n = 53) and 2.4% (n = 2), respectively.

Interestingly, these findings are consistent with a previous study reflected a high rate of ESBL genes in clinical isolates, which clearly indicates the current challenges for the centers for infection control at hospitals and health centers in ICU Qom, Iran. Financial problems and the lack of facilities for molecular typing methods for epidemiology studies, such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), multilocus sequence typing (MLST) that are effective in finding the relationship between strains, and ultimately finding their origin are some of the limitations of our study. The patients admitted to the ICU in our hospitals were not evaluated for the extent of beta-lactamase genes in the urine samples, which can be considered as the strength of the present study.

It is also hoped that in future studies, we will be able to take some effective steps to help in controlling nosocomial infections through molecular typing methods.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results showed that among the examined genes, the most common gene was blaTEM, with a frequency of 61.5% in ESBL-producing E. coli taken from the patients with UTI admitted to the ICU in Qom, Iran.

Due to the high level of drug resistance of the studied isolates, it was very difficult to treat the infections. Accordingly, considering the high rate of drug resistance in our study, further studies are needed to find effective drugs, including nanoparticles, for eliminating these bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics.