1. Background

Aging is increasing almost in all countries (1), and it is predicted that 21.1 percent of the world’s population would be old in 2050. Aging poses major social and economic challenges for governments. The irreversible aging changes are at the levels of molecules, cells, tissues, organs, and systems. Although the reproductive system activity reduces in men and women with increasing age, this reduction is less pronounced in men (2, 3).

The testis changes during aging include a decrease of the mean volume, the number of germinal cells and Leydig cells, and an increase in the thickness of the tunica propria of the basal membrane of seminiferous tubules, reduction of testicular vessels (4) and defects in adrenergic vasoconstriction (5).

The effects of exercise on the reproductive system in the literature are controversial. Some studies indicated that exercise maintains the miotic cell population, decreases lipid peroxidation levels and oxidative stress (6), and prevents aging damages (7, 8). Moreover, it is observed that exercise protects against testicular cancer, prevents diabetes, and controls blood pressure (9). However, some researchers concluded that exercise does not positively affect testicular and spermatogenesis morphological characteristics (10). Moreover, it is demonstrated that long-term exercise may decrease testosterone production, and consequently, spermatogenesis can be impaired by reduced activity of the sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) (11, 12).

Medicinal plants have attracted much attention because of their health benefits, negligible side effects, and reasonable costs (13). Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) is a Lamiaceae family member with thin leaves and purple-blue flowers. Rosemary extract consists of different antioxidants (14), and is used as an antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiulcerogenic, and antidiuretic agent (15, 16). It also increases testosterone levels (17) and recovers seminiferous tubular cell populations’ ratio (18).

Nonetheless, the effects of aerobic exercise and rosemary extract on the male reproductive system remain unclear. Moreover, most researchers in this field have focused on adults.

2. Objectives

This study was designed to evaluate the effects of low-intensity aerobic exercise and rosemary extract with 100 mg/kg concentration on testis histological parameters and the number of spermatogenic lineage cells in aging rats with the ultimate goal of developing an herbal medication for the enhancement of male fertility.

3. Methods

3.1. Animal and Experimental Design

All experiments of this study were conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the Qom University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.MUQ.REC.1398.104). Male Wistar rats (n = 30) weighing ~300 - 350 g were purchased from the Iran University of Medical Sciences Animal Department. The temperature and relative humidity of the animals’ environment were 22 ± 2°C and 40 - 60%, respectively. The 18-month rats were randomly divided into five groups (n = 6 in each group): (1) control group (without treatment, C); (2) gavage group (received the solvent of rosemary extract (in distilled water) and put on a turned-off treadmill daily for 10 minutes, G); (3) exercise group (put on a turned-on treadmill based on an exercise protocol for 12 weeks, E); (4) extract group (received 100 mg/kg of rosemary extract for 12 weeks, EX); (5) exercise and extract groups (received 100 mg/kg of rosemary extract and put on a turned-on treadmill for 12 weeks, EE).

Rosemary extract, including 40% carnosic acid, was purchased from the Hunan Geneham Biomedical Technological Company of China (RAP20-110401). Then, 100 mg/kg of rosemary extract was dissolved in 1 ml of distilled water under a thermal shaker (200 rpm) at 37°C. This concentration was administrated orally five times a week for three months (19, 20).

Rats in the exercise groups were familiarized with the running sessions on a level motor-driven treadmill (Pishroo Andisheah Senate, A1400Y10, Iran) at 10 - 12 m/min for seven days. Then, the running sessions were performed for five days in each week for 12 weeks. The running time and speed increased gradually up to the point that they could run for 1hr at 22 m/min daily in the 12th week.

3.2. Histological Preparation

Each rat was anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of xylazine 10 mg/kg and ketamine 100 mg/kg. The animals were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer solution (pH: 7.4). After perfusion, the abdomen was exposed, and the

position of the testes was observed. The testis tissue was separated from the epididymis and other tissue. Then it was placed in the 10% formalin overnight. The samples were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and cleared in xylene. After paraffin embedding, the sections with 5 µm thickness were prepared by a microtome rotary (LEICA RM 2235). They were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H & E) and Mallory trichrome according to the protocol (21). The sections were visualized under an optical microscope (Eclipse E200-LED, Tokyo, Japan). Then, nine images at 400X magnifications were randomly selected to measure the mean seminiferous tubular diameter, luminal diameter, and epithelial height in different groups. The five random fields were chosen and measured by the Image J analysis software. The means of seminiferous tubular diameter were measured by 2 diameters from the basement membrane to the border of the epithelial cells in seminiferous tubules. The luminal diameter was calculated by measuring the lumen’s vertical and horizontal diameters to the epithelial cells’ border. Also, the average epithelial height was measured in 4 areas from the basement membrane to the lumen in each seminiferous tubule. Finally, the population of spermatogonia, primary spermatocyte, and spermatozoa cells was calculated (using the Image J software).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS 24 software and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the significant differences between groups. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Histological Analysis of the Testes

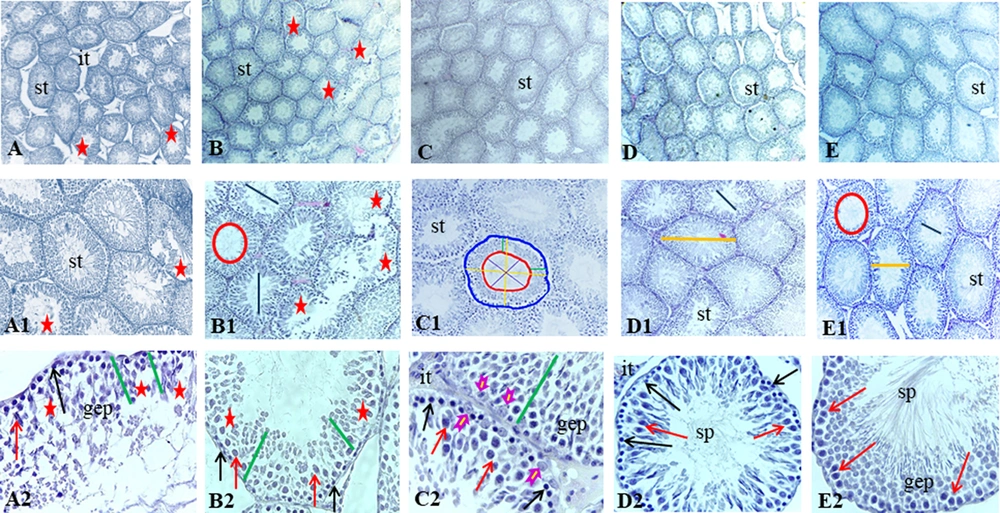

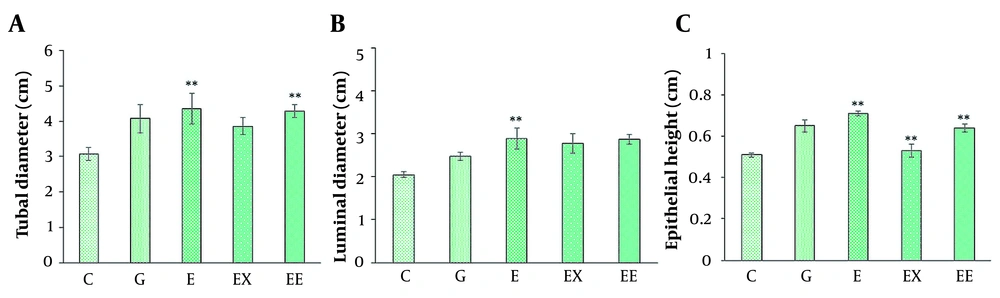

The seminiferous tubular diameter, luminal diameter, and epithelial height were measured (Figures 1 and 2). We observed the destruction of germinal epithelium in the control group, while in the exercised animals, pathological changes were not detected in seminiferous tubules. A significant increase in tubular diameter was found in E and EE groups compared with the control group (P < 0.01). Also, compared with the control group the luminal diameter increased extensively following the exercise, but there was no significant difference between the other groups (P > 0.05).

A, Histological images of testicular tissue following Mallory trichrome staining under light microscopy in different groups: (1) control (A-A2), (2) gavage (B-B2), (3) exercise (C - C2), (4) rosemary extract (D-D2), (5) exercise and extract (E-E2) groups (× 40, × 100, and × 400 magnification). Seminiferous tubule (st), germinal epithelium (gep), interstitial tissue (it), spermatozoa cells (sp). Detachment and destruction of germinal epithelium (red star), Spermatogonia cells (black arrow), primary spermatocyte (red arrow). Sertoli cell (arrowhead). Tubal and luminal circumferences are demonstrated by blue and red circles, respectively. The yellow line points to seminiferous tubule diameter, the purple line shows the luminal diameter, and the epithelial height is marked by the green line.

A, The comparison of average seminiferous tubule diameter in different groups; B, The comparison of mean luminal diameter in different groups; C, The comparison of epithelial height in seminiferous tubules in different groups (mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01) indicates a significant difference between the control group with other groups).

The epithelial height significantly increased with aerobic exercise with/ without rosemary extract compared with the control group (P < 0.01), and the highest mean epithelial height was observed in the E group (0.716 ± 0.018).

3.2. Effect of the Rosemary Extract and Aerobic Exercise on the Spermatogenic Lineage Count

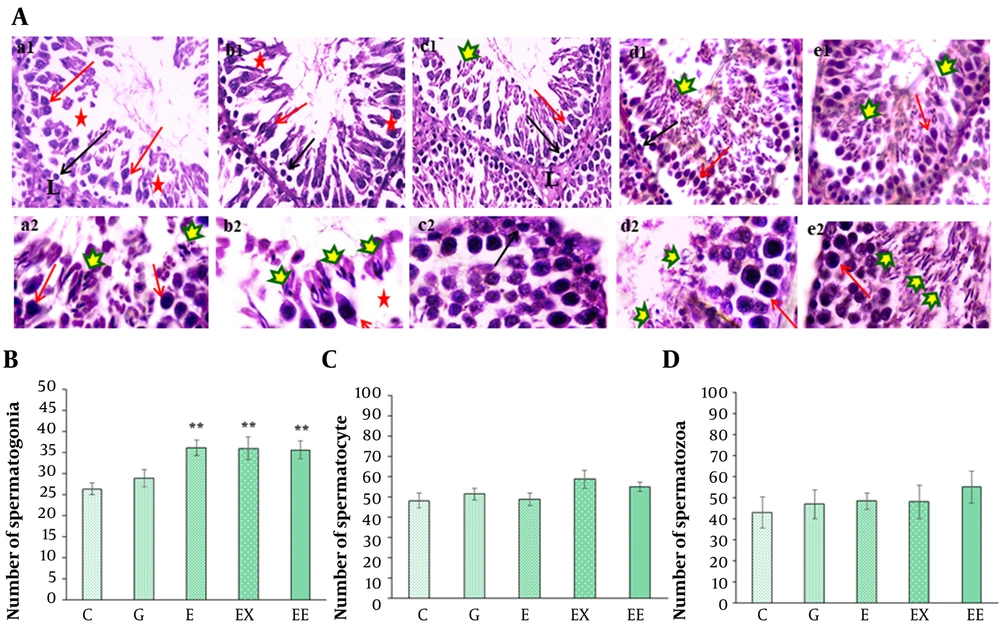

Figure 3A shows the light microscope images of testis tissue in various groups. The histological evaluation showed that rosemary extract or/and exercise had caused a proliferation in the number of spermatogonia cells compared with the control group (P < 0.01) (Figure 3B). Although the highest number of primary spermatocyte cells was observed in the presence of rosemary extract (58.71 ± 4.4), there was no significant difference in the number of primary spermatocytes (P > 0.05) (Figure 3C). In addition, the mean number of spermatozoa cells was about 55.19 ± 7.6 in the group undertaking exercise. However, there was no significant difference in the number of spermatozoa cells between various groups (P > 0.05) (Figure 3D).

A, H&E staining of spermatogenesis lineage in seminiferous tubules in different groups: (1) control (a1-a2), (2) gavage (b1-b2), (3) exercise (c1-c2), (4) rosemary extract (d1-d2), (5) exercise and extract (e1-e2) groups (× 100 in a1-e1 and × 400 in a2-e2 images). Detachment and destruction of the germinal epithelium (red star), Leydig cell in interstitial tissue (L), G group, Spermatogonia cells (black arrow), primary spermatocyte (red arrow), and spermatozoa cells are shown by different markers in different groups; B, The comparison of the mean number of spermatogonia cells among different groups; C, The comparison of the mean number of primary spermatocytes in different groups; D, The comparison of the mean number of spermatozoa cells in different groups (**P < 0.05 show a significant difference compared with the C group).

5. Discussion

The present findings demonstrated that low-intensity exercise could improve some histological features of testicular tissue. Also, this study revealed that the consumption of rosemary and training exercises could increase the number of spermatogonia cells. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in the number of primary spermatocyte and spermatozoa cells between different groups. Additionally, the empty spaces between seminiferous tubules were smaller in the groups that undertook exercise. However, as we did not compare different exercise intensities and various rosemary doses, the findings may not be accurately generalized.

Testicular parameters are changed by aging (22), and aging may deteriorate male fertility and cause deficiencies in the reproductive axis (23). The present study investigated the effects of low-intensity aerobic exercise and rosemary extract on the testis morphology of old male rats. Moreover, as the spermatogenic process takes approximately 53 days in rats (24), we evaluated the effect of the administration of the herbal extract and exercise on male fertility in 84 days.

Exercise can make alternations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Moreover, the effects of exercise on the testicular tissue depend on its intensity and duration, and high-intensity exercises have a more deleterious effect on reproduction (12). One research comparing the results of low and high exercise capacity on apoptosis and spermatogenesis in rat testes found that low exercise may increase spermatogenesis via decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) (25). In another study, it was demonstrated that aerobic exercise 5 times a week for eight weeks could improve fertility and sperm parameters in diabetic rats by decreasing oxidative stress (26). Another research demonstrated that high-intensity exercise can result in spermatogenesis failure and reduction in the survival of germinal lineages and Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules (27). Moreover, it demonstrated that exercise can improve semen parameters, sperm DNA integrity, and pregnancy rate in infertile men (28).

Recently, several studies have focused on the effect of different plant extracts on the function of different human body systems and healthy complexion (29-32). Momordica charantia fruit contains flavonoid components that can regulate cholesterol and lipoproteins levels (33). Rosemary, which contains phenolic diterpenes, flavones, and steroids, has been widely studied for pharmaceutical purposes (34). It also contains different types of triterpenes, including carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid, carnosol, rosmanol, betulinic acid, and ursolic acid (35). The rosemary extract can regulate serum testosterone concentrations through a direct effect on the male sexual hormone system (36).

There is controversy about the effect of rosemary on the reproductive system in different concentrations. On the one hand, it reduces the testicular DNA damage induced by Etoposide in a low dose of rosemary extract (37). On the other hand, high dose consumption of rosemary can have detrimental effects on fertility (24). Moreover, in one study, rosemary leaves improved semen quality and fertility in rabbits (38). Another study evaluating the effect of the ethanolic extract of rosemary on injured testicular tissue in albino rats demonstrated that this extract increased male hormones and catalase (CAT) activity (39). Rosemary extract in 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg doses improved heat stress side effects, demonstrating that this extract can be a stress moderator with the potential to regulate spermatogenesis and sexual hormones in warm climates (36). Generally, the dosage of rosemary extract administration has a key role in regulating the reproductive system.

The results of the current study demonstrated that the daily administration of rosemary extract (100 mg/kg), with or without exercise, can confer some benefits on spermatogonia cell populations. Nonetheless, there was no significant difference in other spermatogenesis lineage cells between various groups. As there are 14 stages and 12 waves in the rat's spermatogenesis process (40), more time may have been needed for the differentiation of spermatogonia to primary spermatocyte and spermatozoa cells in E, EX, and EE groups.

This study demonstrated that low-intensity aerobic exercise could improve some testis tissue parameters in aging. However, although daily rosemary extract (100 mg/kg) positively affected epithelial height and the number of spermatogonia cells, it was not as beneficial as exercise. Therefore, we conclude that low-intensity exercise and rosemary extract with specific concentrations could be recommended as a lifestyle-modifying approach against the deteriorating effects of aging on male fertility. Moreover, it can be proposed that future research should be focused on the impact of different concentrations of the extract and various exercise intensities on male fertility in aging.