1. Background

Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases are debilitating neurological conditions that affect millions of people worldwide. Current treatments for these diseases are limited and often have significant side effects, highlighting the need for new therapeutic options. Octreotide is a synthetic peptide that has been shown to interact with the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, a key mediator of neuronal activity in the brain. The GluN2B subunit of the NMDA receptor is of particular interest due to its involvement in synaptic plasticity and learning and memory processes. In this study, we aimed to investigate the potential role of octreotide in regulating the function of GluN2B through computational molecular docking, building on previous studies showing the effectiveness of computational approaches for evaluating receptor-ligand binding energies (1). We hypothesize that octreotide may have a therapeutic effect on nervous diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s by modulating the interaction between GluN2B and other proteins involved in neuronal signaling, as suggested by the work of Kim et al. (2).

2. Methods

In this study, we conducted a computational investigation of the binding interactions between a ligand and a macromolecule. Firstly, we selected a suitable receptor structure and optimized it, followed by the prediction of its druggable binding sites (pockets). We constructed a simulation box and performed molecular docking simulations in each pocket’s designated region upon identifying the specific residues of the chosen pockets. We investigated the effect of octreotide, which controls blood lipids, on one of the proteins involved in epilepsy. Our ChemBio Draw (3) program is for the preparation and creation of the 3D structure of octreotide. Also, molecular optimization of the 3D structure of this drug was done using this program. After examining the genes involved in epilepsy on the DisGeNET (4) server, we selected the ionotropic glutamate receptor NMDA type subunit 2B gene with the symbol GRIN2B. We studied its supplementary information on the UniProt (5) server. The three-dimensional structure of this protein was simulated using the AlphaFold (6) server, and the steps of preparing this structure for docking were performed by the Chimera (7)) program. Also, these receptor envelopes were identified using the PockDrug (8) server. The ProCHECK (9, 10) server has checked the predicted structure of the protein in question. The docking and molecular simulation process was done using the AutoDock Vina 1.2.0 (11, 12) algorithm under the Chimera user interface. The analysis of docking results has been done by the PDBsum (13) and Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (14) servers. The images were prepared by the VMD (15) program.

3. Results

We examined the structure and quality of the GluN2B subunit of the NMDA receptor protein. We then identified and measured all druggable sites of the receptor, selecting the most promising ones for further investigation. We analyzed the interaction between octreotide and the GluN2B subunit using molecular docking techniques. Our results include the preparation of the protein receptor, identification of its druggable pockets, and the findings from molecular docking analysis.

3.1. Receptor Protein Preparation

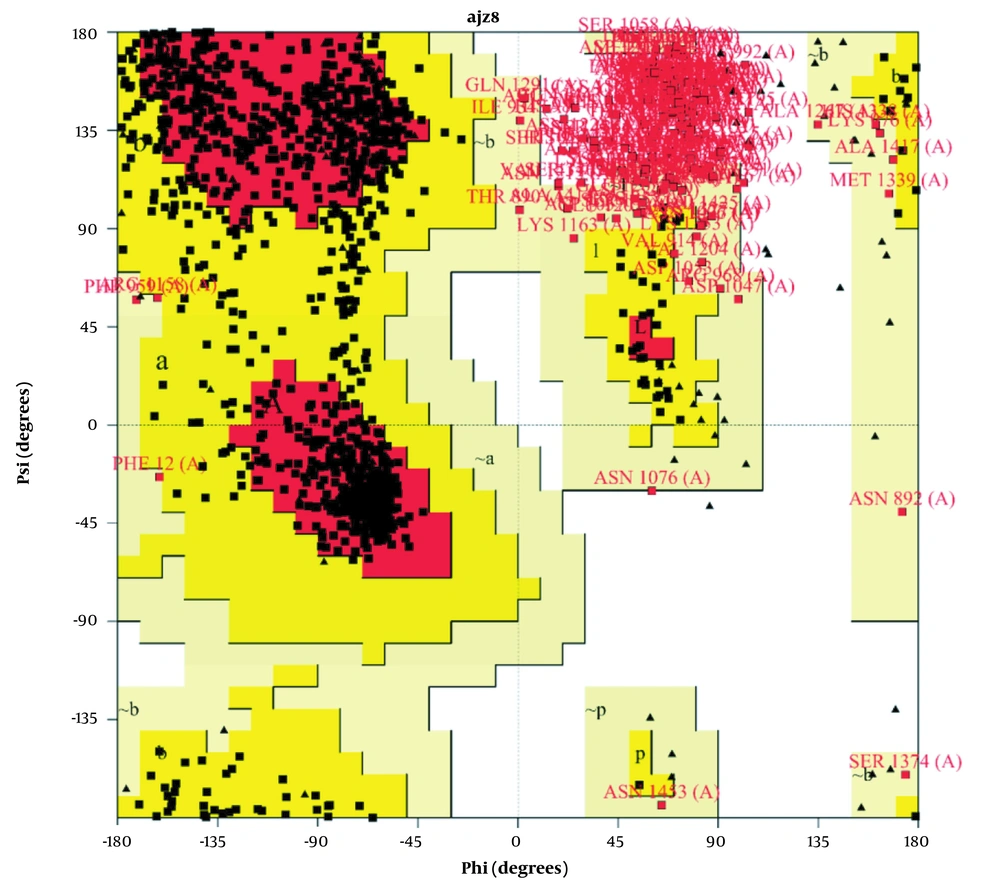

Before performing molecular docking, we evaluated the structure simulated by AlphaFold by the ProCHECK server. The results of this evaluation are presented in the form of a Ramachandran diagram in Figure 1.

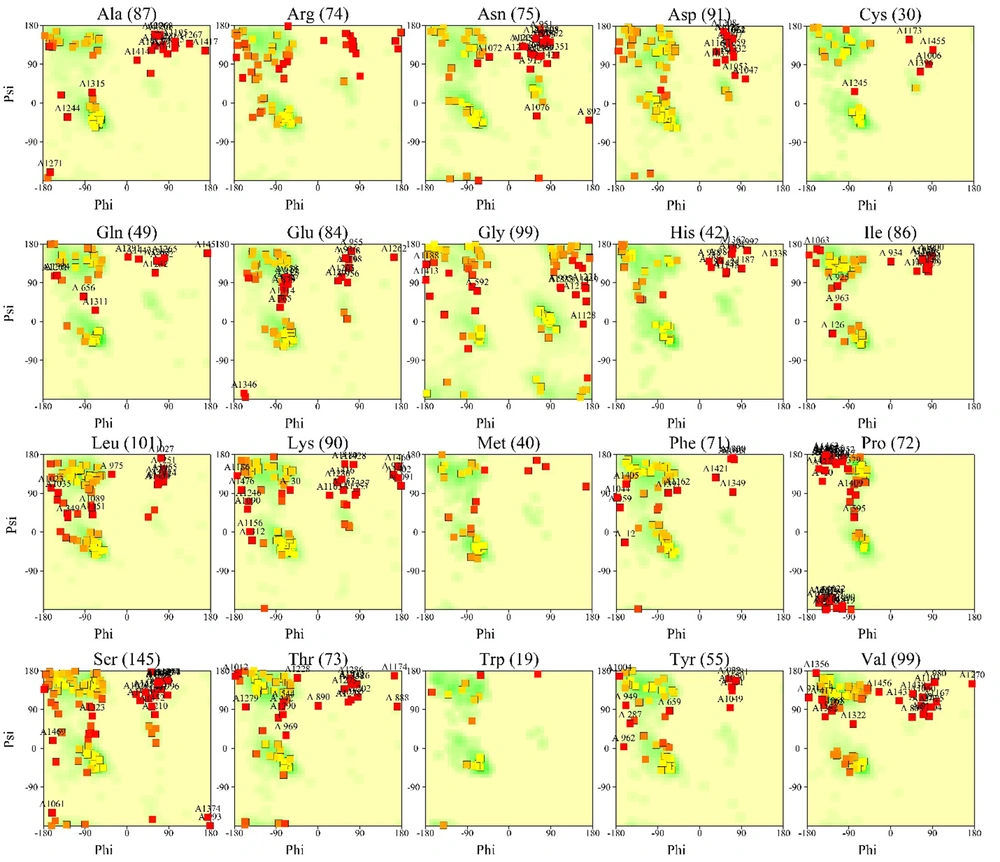

Also, Ramachandran graphs by separating this protein residue are mentioned in Figure 2.

Further, the supplementary results related to Figure 1 are reported in Table 1.

| Plot Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Residues in most favored regions [A, B, L] | 905 | 69.0% |

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 245 | 18.7% |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 61 | 4.7% |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 100 | 7.6% |

| Number of non-glycine and non-proline residues | 1311 | 100.0% |

| Number of end-residues (excl. GLY and PRO) | 3 | |

| Number of glycine residues (shown as triangles) | 99 | |

| Number of proline residues | 72 | |

| Total number of residues | 1485 | |

Supplementary Results for Figure 1

After checking the structure of the desired protein, we checked the pockets of the GluN2B receptor.

3.2. Identification of Druggable Pockets

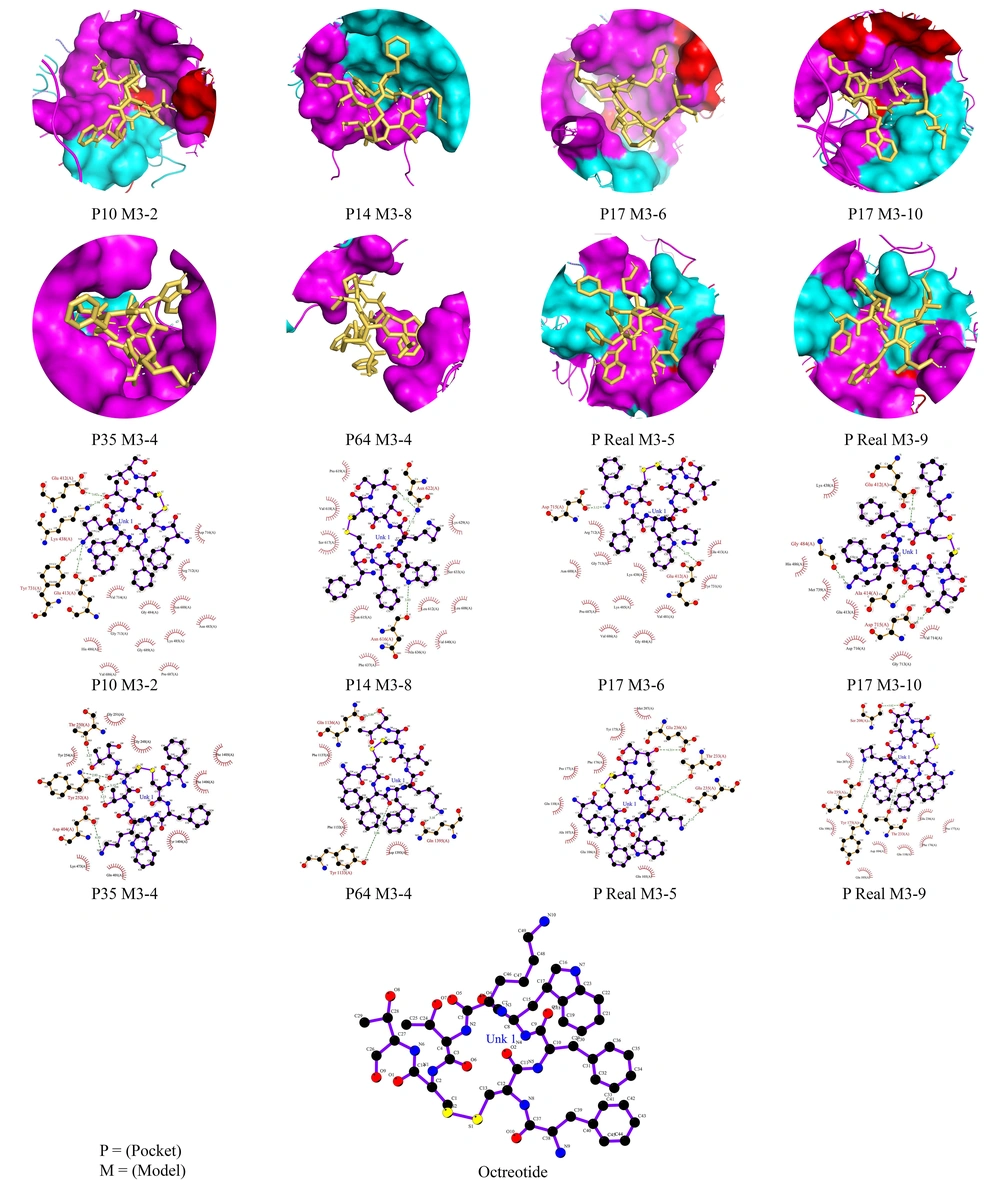

The Pocket Drug server detected eighteen packets. Only the molecular docking results of 5 out of 18 pockets were acceptable. The results of this simulation are presented in full detail in Figure 3. In 2012, the relationship between ifenprodil and a pocket of the GluN2B subunit of the NMDA gene was investigated.

Eighteen pockets were found in this target protein after the simulations; 13 have fewer than 14 residues, and 5 have more than 14 residues. The results of our analysis are listed below. We selected the best 18 pockets (P35, P64), (P10, P14, P17).

The GluN2B residues and equivalent residues that interact with ifenprodil are listed in Table 2.

| Amino Acid | Num |

|---|---|

| Pro | 78 |

| Ile | 82 |

| Glu | 106 |

| Ala | 107 |

| Gln | 110 |

| Ile | 111 |

| Phe | 114 |

| Tyr | 175 |

| Phe | 176 |

| Pro | 177 |

| Met | 207 |

| Thr | 233 |

| Glu | 236 |

GluN2B Residues and Equivalent Residues Interacting with Ifenprodil

3.3. Molecular Docking Analysis

The docking results for GluN2B Residues and Equivalent Residues Interacting with ifenprodil were reported in Table 2 and are presented in Table 3.

| Model No. | Score | RMSD u.b. | RMSD l.b. | H Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | -6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 |

| 3.5 | -5.4 | 1.316 | 1.763 | 4 |

| 3.9 | -5.2 | 2.746 | 4.958 | 3 |

Docking Results for Reported Pockets

The full results of the analysis are reported in Table 4 (Pockets 35 and 64), Table 5 (Pockets 10 and 14), and Table 6 (Pocket 17).

| Pocket and Model No. | Score | RMSD u.b. | RMSD l.b. | H Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P35 | ||||

| 3.4 | -6.1 | 3.937 | 6.973 | 8 |

| P64 | ||||

| 3.1 | -5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 3.3 | -5.0 | 4.036 | 9.342 | 2 |

| 3.4 | -5.0 | 4.259 | 6.906 | 2 |

Results of Pocket Num 35, 64 (Less Than 14 Residues)

| Pocket and Model No. | Score | RMSD u.b. | RMSD l.b. | H Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P10 | ||||

| 3.1 | -6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 |

| 3.2 | -6.4 | 2.718 | 7.384 | 3 |

| 3.9 | -5.4 | 1.776 | 2.286 | 3 |

| P14 | ||||

| 3.1 | -6.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 |

| 3.2 | -5.6 | 2.557 | 6.667 | 2 |

| 3.8 | -4.5 | 1.355 | 2.152 | 2 |

Results of Pocket Num 10, 14 (More Than 14 Residues)

| Pocket and Model No. | Score | RMSD u.b. | RMSD l.b. | H Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P17 | ||||

| 3.1 | -6.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 |

| 3.6 | -5.7 | 1.308 | 1.875 | 4 |

| 3.10 | -5.5 | 3.902 | 8.979 | 6 |

Results of Pocket Num 17 (More Than 14 Residues)

Due to the extensiveness of the information, the rest of our analysis results, along with their images, are given below.

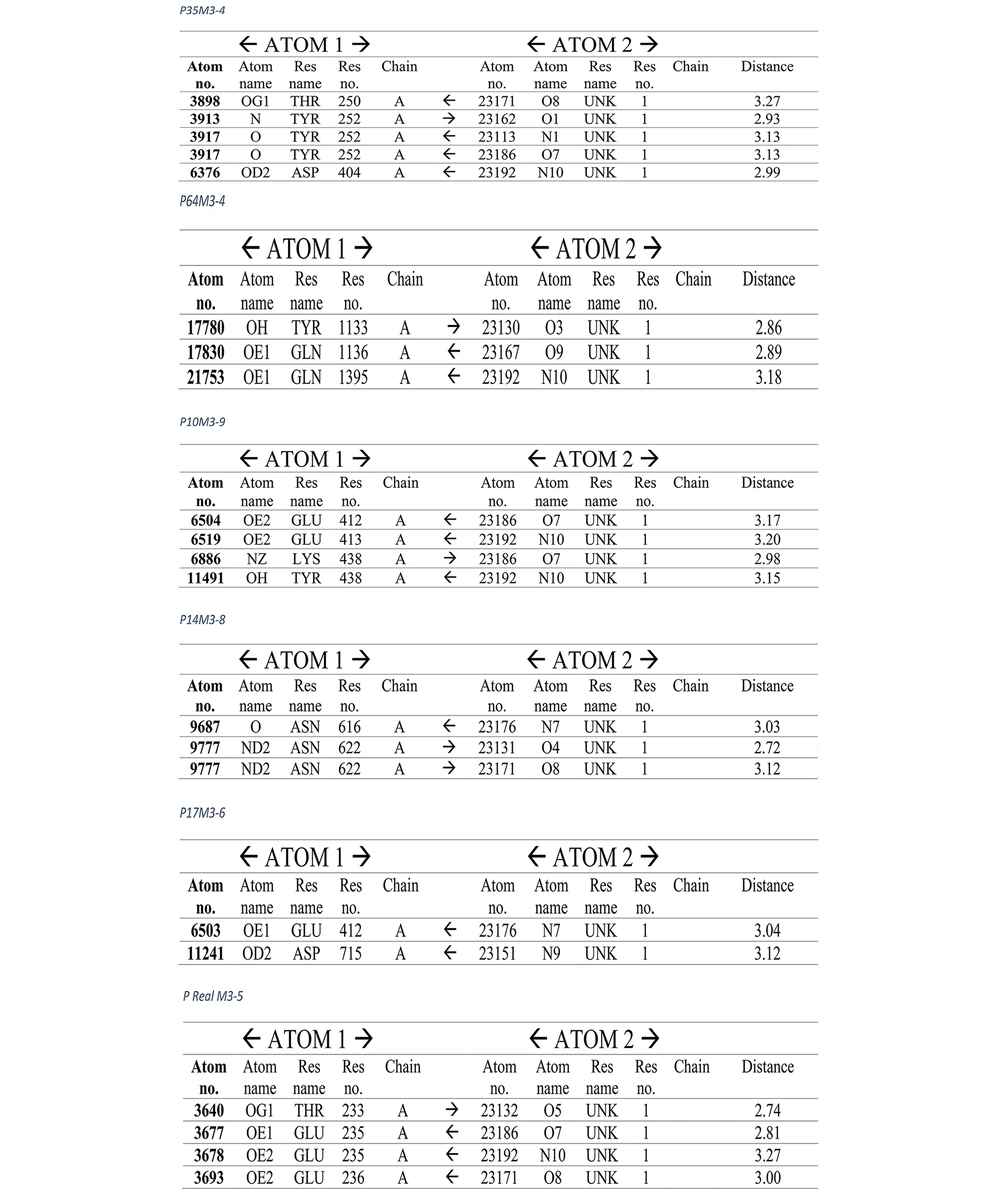

The hydrogen bonds established between the ligand and our receptor and their bond distance are also mentioned in the figure below.

4. Discussion

There were no specific crystallographic structures for the related protein. As a result, we obtained our protein structure using the AlphaFold server. In examining this structure, we observed that the continuous simulation could have been better quality but more comprehensive than the existing crystallographic structures. Examining the Ramachandran diagram of NMDA protein, we saw the presence of amino acids in the central regions of the diagram, which had high accuracy in simulation. As shown in Figure 1, out of 1485 residues in our protein, 905 residues are present in the central regions of A, B, and L, constituting 69.0% of the total residues in our protein. Two hundred forty-five residues of our protein are located in acceptable regions for our structure validation, constituting 18.7% of our residues (regions a, b, l). Sixty-one residues are also located where we can confirm their authenticity (regions a’, b’, l’). However, our 100 residues are in regions that are unacceptable to us and were not correctly cloned. In total, we can safely say that 92.4% of our protein structure has been correctly simulated and shown in picture number 1 in most black squares. The remaining 7.6% are also displayed as red squares. All glycine residues in our protein structure, 99 in number, are shown as triangles in the diagram. Glycine is symmetrical in the Ramachandran diagram.

We selected 18 best-scoring envelopes for this protein, but after viewing the docking results, we reported only five that provided acceptable results. We also selected an envelope according to studies done in the past and measured its molecular docking. The amino acids of this envelope are reported separately in Table 2.

Among our five simulated pockets, 2 of them, P35 (Pocket 35) and P64 (Pocket 64) have less than 14 residues. Three of them, named P10 (Pocket 10), P14 (Pocket 14), and P17 (Pocket 17), contain more than 14 residues.

The results of molecular docking, which contain binding energy (score), RMSD u.b, RMSD l.b, and hydrogen bonds, are reported separately in Tables 4, 5, and 6. Also, the results related to our pocket obtained in the studies (real pocket) are listed in Table 3.

The docking done in Table 3 had ten different modes of ligand placement in the receptor, of which only 3 of the best were reported. According to this report, models 1, 5, and 9 each had energies of -6.0, -5.4, and -5.2 kcal/mol. Our standard value for this energy is that the smaller it is -5, the better our result. The fluctuation of RMSDs in this envelope is much less, and the formed bonds are more stable and reliable in addition to the high number. Model number 1 in the analysis of this envelope, as it is an essential criterion, has fixed RMSDs. As a result, model number 5 of docking is this pocket with an average bond distance of 2.95 angstroms to get closer to the intermolecular conditions. The connection between ligand and receptor is fully reported in Figure 3. Similar to the hydrogen bonds we have in our analysis, in the research work, we observed the connection between ifenprodil and our subunit (GluN2B) by Mohamed El Fadili et al. (16). This drug is used as an inhibitor of the NMDA receptor and GIRK channels (17, 18). In some countries, such as Japan and France, it is used as a cerebral vasodilator (19). This drug has also been studied to prevent tinnitus (20).

The rest of the studies conducted with our receptor include a limited range of its amino acids. For example, in the work of Gawaskar et al., their analysis only covers amino acids 1290 to 1310 of GluN2B, while our work simulates all 1428 amino acids available (21).

These favorable conditions exist only for our other three envelopes with more than 14 amino acids. Envelopes No. 10, 14, and 17 of their valid models, which are 3.9, 3.8, and 3.6, each have energies of -5.4, -4.6, and -5.7, and their average links are 3.12, 2.95, and 3.08. All hydrogen bonds are mentioned in detail in Figure 4.

Some neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease, have been associated with inhibiting GluN2B activity in neurons (22). GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors have been linked to memory formation and synaptic plasticity, according to studies (23). Long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), two types of synaptic plasticity that are crucial for the development of learning and memory, have been demonstrated to be impaired by the inhibition of GluN2B activity (24).

The GluN2B subunit of NMDA receptors has been demonstrated to be inhibited by the somatostatin analog octreotide. According to studies, octreotide lowers GluN2B expression in the brain, which lowers NMDA receptor function. This action is believed to lessen glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, which is advantageous for neuroprotection. Furthermore, octreotide has been demonstrated to lessen anxiety in animal models, possibly due to its impact on GluN2B (25-27).

Antibodies known as GluN2B antagonists prevent the GluN2B component of the NMDA receptor from performing its normal activity. The therapeutic potential of these substances for treating neuropsychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression, has been researched. By decreasing the activation of NMDA receptors, glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity is reduced, which may lessen neuroinflammation and enhance cognitive performance. These drugs are being studied for their potential to treat neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and schizophrenia (25, 26).

Octreotide is hence regarded as a GluN2B receptor antagonist, except it indirectly inhibits this receptor’s activity by lowering its expression.

This work looked at how octreotide directly affects the GluN2B receptor. According to the data, octreotide could likely operate as a direct inhibitor of this receptor and decrease the expression of GluN2B (25, 26).