1. Background

Consanguineous marriage is a type of interfamilial union, defined as the marriage between two individuals who are related as second cousins or closer, with an inbreeding coefficient (F) equal to or higher than 0.0156 (1). Consanguineous marriage is a preferred traditional practice and is even socially supported in many communities worldwide (2, 3). Globally, it has been estimated that nearly 8.5% of children are born to consanguineous unions, with the most common type being marriage between first cousins (4, 5).

From a social and economic standpoint, consanguineous marriage has several advantages, such as a lower risk of divorce and a higher likelihood of marriage survival (6). However, inbreeding marriage has been regarded as a global health issue, with growing recognition of the impact of consanguinity on health and illness. The main concern of consanguineous unions is the increased genetic homogeneity of inbred individuals (7). The detrimental effects of consanguineous marriages result from the homozygosity of genes coding for autosomal recessive diseases in the population, which increases the risk of genetic disorders among consanguineous progeny (8). Higher rates of consanguinity can result in multiple genetic diseases among affected individuals, including congenital heart diseases, renal diseases, and rare blood disorders. Conversely, the effect of consanguinity on common multifactorial diseases and cancers is less predictable and requires more research (9).

Approximately one-fifth of the global population resides in areas where there is a preference for consanguineous marriages, leading to a distinct geographical distribution of such unions worldwide (5). Regions with high rates of consanguineous marriage include the Middle East, West Asia, and North Africa (www.consang.net). However, there is substantial variation in the prevalence of consanguineous marriage within and between countries (5). For instance, an extensive examination of Pakistan Demographic Health Surveys over three decades, from 1990 to 2018, revealed a significant occurrence of consanguineous marriage, reaching a notable prevalence rate of 63% (10). In contrast, data from Saudi Arabia showed that 39.8% of marriages were consanguineous (11).

Although North America and Western Europe appear to be experiencing a decline in inbreeding over time (5), certain developing nations, including Pakistan and Iran, have shown a discernible upward trend (10, 12). For instance, an examination of the pattern in consanguineous marriage among three generations of Iranians (marriages before 1948, between 1949 and 1978, and after 1979) revealed a rise from 8.8% to 16.6% and 19%, respectively (13).

Consanguinity is associated with ethnicity, family structure, language, and marriage arrangements (14). Several demographic and social factors have also been linked to close kin marriage, including low socioeconomic status, low levels of education, early age at first marriage, rural residence, more traditional lifestyles, and women's employment status (5, 15).

In the Iranian communities researched thus far, the least affluent individuals, particularly rural couples, older marriage cohorts, younger marrying ages, and women with less formal education, have been found to have the highest percentages of consanguineous unions (16, 17). Other factors associated with relative marriage include having consanguineous parents, religious reasons for choosing a spouse, never-employed women, and those unaware that consanguinity may lead to serious diseases (18, 19). Contrary to previous studies, some populations report a high prevalence of marital unions between close relatives among individuals with higher levels of education (14) or higher socioeconomic status (20). Furthermore, it has been found that religion impacts the frequency of consanguineous marriage (5).

Sistan and Balouchestan Province, Southeast Iran, is home to two major traditional ethnic groups, Balouch and Sistani. Endogamy, the practice of marrying within a specific ethnic, class, or social group (21), is common in this province. As a result, genetic disorders and congenital malformations have been identified as important causes of mortality in children under five years of age in this province (22). In such a traditional society, the choice of a future spouse is often made by the parents. Although arranged marriages, where parents plan and arrange marriages for their children when they are young, are uncommon, some instances have been documented in very traditional families.

2. Objectives

Consanguinity is a main feature of the family structure in Sistan and Balouchestan Province. However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the prevalence and pattern of close kin marriages in this area. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of consanguinity among the study population, the distribution of marriages by the type of relationship, and the socio-demographic characteristics associated with consanguineous unions.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2020 and March 2021 at the Pre-Marriage Counselling Center (PMCC) in Zahedan, southeast Iran. According to an epidemiological study conducted on 12 ethnic/religious groups in Iran, it was estimated that around 40% of marriages were consanguineous (17). Hence, for sample size calculation, the reported prevalence of consanguineous marriages was considered as P = 0.4, with α = 0.05 and d = 0.05. Considering the number of predicting factors in the logistic model, the sample size was calculated to be 738 couples. A convenient sampling method was used for recruiting couples attending the PMCC in Zahedan. After receiving their verbal consent, subjects willing to take part in the study were interviewed.

3.2. Data Collection

Trained genetic counselors conducted face-to-face interviews using a 25-item structured questionnaire to gather all the necessary information. The questionnaire was developed based on a review of the literature and the National Guidelines for Integrating Genetic Disease Control and Prevention Services into the Iranian Health System, Fourth Edition, 2017 (23).

The questionnaire consisted of four parts: The first part included nine questions on the socio-demographic characteristics of the study subjects. The second part included five questions on the socio-demographic characteristics of the parents, their consanguinity status, and the father's polygamy. The third part contained eleven questions on the history of congenital malformations and genetic disorders in the study subject's household. The fourth section of the questionnaire was used for drawing the family tree and calculating the inbreeding coefficients (F) for couples with consanguineous unions.

Marriages between couples were classified into six groups: Double first cousins, first cousins, first cousin once removed, second cousins, distant relatives (i.e., less than second cousins), and non-relatives. Consanguineous marriages were defined as unions between individuals who were second cousins or more closely related (1).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics methods such as counts and percentages were used to present categorical variables. The distribution of covariates between the two groups was compared using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted using the forward likelihood ratio method to identify the correlates of consanguineous marriages. All variables that showed a significant association with consanguineous marriages at a significance level of 0.2 or less in the binary logistic regression models were incorporated into the final model. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS version 23 statistical software package (Chicago, IL).

4. Results

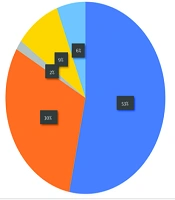

A total of 738 couples participated in this study. The participants' ages ranged from 13 to 61 years old, with a mean age of 23.06 ± 6.06 years. The degree of relationship between the couples is illustrated in Figure 1. Among the marrying couples, 46.7% were consanguineous and 53.3% were not related. First cousin marriages accounted for the majority of the unions (30.2%). Based on the pedigrees of the marrying couples, the average inbreeding coefficient (F) for consanguineous couples was calculated as 0.0516 (95% CI: 0.0481 - 0.0551).

As presented in Table 1, couples younger than 18 years of age were more likely to have a consanguineous marriage compared with older age groups (59.4% versus 44.8% and 21.4%). Consanguineous unions among college-educated grooms and brides and government employees were the lowest: 25.2%, 13%, and 22.1%, respectively. Compared to urban dwellers, consanguineous marriages were more common in rural areas (58% versus 42.9%).

| Variables | Consanguineous (n = 690) | Non-Consanguineous (n = 786) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (y) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 18 | 142 (59.4) | 97 (40.6) | |

| 18 - 35 | 530 (44.8) | 653 (55.2) | |

| > 35 | 18 (21.4) | 66 (78.6) | |

| Education | < 0.001 | ||

| Illiterate | 33 (37.1) | 56 (62.9) | |

| Primary | 210 (54.7) | 174 (45.3) | |

| Secondary | 176 (58.3) | 126 (41.7) | |

| High school | 204 (45.7) | 242 (54.3) | |

| University | 64 (25.2) | 190 (74.8) | |

| Groom's occupation | < 0.001 | ||

| Government job | 13 (22.1) | 46 (77.9) | |

| Worker | 53 (60.2) | 35 (39.8) | |

| Self-employed | 207 (45.5) | 248 (54.5) | |

| Unemployed | 36 (63.2) | 21 (36.8) | |

| Retired/pensioner | 36 (45.6) | 43 (54.4) | |

| Bride's occupation | < 0.001 | ||

| Government job | 4 (13.0) | 27 (87.0) | |

| Housewife | 293 (49.4) | 300 (51.1) | |

| Worker/self-employed | 48 (42.1) | 66 (57.9) | |

| Residence | < 0.001 | ||

| Urban | 471 (42.9) | 627 (57.1) | |

| Rural | 219 (58.0) | 159 (42.0) | |

| Ethnicity | < 0.001 | ||

| Balouch | 458 (47.2) | 513 (52.8) | |

| Sistani | 218 (49.8) | 220 (50.2) | |

| Others | 14 (20.9) | 53 (79.1) | |

| Income | < 0.001 | ||

| Good | 44 (31.9) | 91 (68.1) | |

| Medium | 309 (44.4) | 387 (55.6) | |

| Poor | 337 (52.3) | 308 (47.7) | |

| Parental consanguinity | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 307 (53.3) | 269 (46.7) | |

| No | 383 (42.6) | 517 (57.4) | |

| Polygynous father | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 453 (45.0) | 555 (55.0) | |

| No | 237 (50.6) | 231 (49.4) | |

| Consanguineous marriage in family members | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 648 (93.9) | 42 (6.1) | |

| No | 637 (84.9) | 113 (15.1) | |

| History of genetic disorders in the family members | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 64 (56.6) | 49 (43.4) | |

| No | 626 (45.9) | 737 (54.1) | |

| History of musculoskeletal disorders in the family members | 0.035 | ||

| Yes | 23 (67.6) | 11 (32.4) | |

| No | 667 (46.2) | 775 (53.8) | |

| Marriage arrangement | < 0.001 | ||

| Parents | 609 (68.2) | 285 (31.8) | |

| Others | 81 (14.0) | 501 (86.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b P-Value for chi square test.

Inbreeding was more common among the Balouch and Sistani ethnic groups, and among middle- and low-income couples, with the differences being statistically significant (P < 0.001). The consanguineous marriage group included a higher percentage of couples with polygynous fathers, those with a history of consanguineous marriage in family members, and couples whose parents were related. Parent-arranged marriages accounted for a significantly higher percentage of consanguineous marriages (68.2%) compared to just 14% of marriages arranged by people other than parents (P < 0.001).

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the factors that influence the likelihood of consanguineous marriages (Table 2). Couples under the age of 18 and between 18 - 35 years old were 5.3 and 2.9 times more likely to enter into consanguineous marriages compared to individuals over the age of 35. Illiterate couples, as well as those with educational backgrounds below university level, were found to have a 1.7 to 4.1 times greater likelihood of entering into consanguineous marriages compared to individuals with a university degree. Regarding the place of residence, couples living in rural areas had a 1.5 times higher likelihood of engaging in consanguineous unions compared to those residing in urban areas (OR= 1.55, 95% C.I.: 1.13 - 2.13). Consanguineous marriages were over three times more prevalent among individuals with a Balouch and Sistani ethnic background compared to couples from different ethnicities. Conversely, individuals with medium and low incomes had a 1.7- and 2.3-fold higher likelihood of consanguineous marriages, respectively, compared to couples with good incomes. Parental consanguinity greatly raised the likelihood of consanguineous unions between the couples getting married (OR= 1.57, 95% C.I.: 1.04 - 1.66). Similarly, marriages arranged by parents significantly increased the chance of consanguineous marriages compared to marriages arranged by individuals other than parents (OR= 12.97, 95% C.I.: 9.75 - 17.25).

| Variables | Crude OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI] | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (y) | |||

| < 18 | 5.367 [2.99 - 6.14] | 3.32 [1.74 - 6.30] | 0.008 |

| 18 - 35 | 2.98 [1.51 - 4.41] | 2.58 [1.45 - 4.61] | 0.041 |

| > 35 | Ref | Ref | |

| Education | |||

| Illiterate | 1.69 [0.12 - 2.91] | 1.79 [1.06 - 3.03] | 0.045 |

| Primary | 3.60 [2.54 - 4.41] | 3.37 [2.35 - 4.83] | 0.024 |

| Secondary | 4.20 [2.92 - 4.87] | 4.15 [2.86 - 6.01] | 0.015 |

| High School | 2.52 [1.61 - 3.60] | 2.42 [1.72 - 3.41] | 0.032 |

| University | Ref | Ref | |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 1.83 [1.44 - 2.32] | 1.55 [1.13 - 2.13] | 0.006 |

| Urban | Ref | Ref | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Balouch | 3.37 [1.67 - 4.93] | 3.03 [1.58 - 5.79] | 0.011 |

| Sistani | 3.75 [ 1.92 - 5.26] | 3.05 [ 1.92 - 5.26] | 0.004 |

| Others | Ref | Ref | |

| Income | |||

| Poor | 2.34 [1.25 - 3.37] | 1.99 [0.73 - 2.35] | 0.108 |

| Medium | 1.71 [0.43 - 2.44] | 1.44 [0.26 - 2.74] | < 0.001 |

| Good | Ref | Ref | |

| Parental consanguinity | |||

| Yes | 1.54 [1.24 - 1.90] | 1.57 [1.04 - 1.66] | 0.022 |

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| History of genetic disorders in the family members | |||

| Yes | 1.53 [0.06 - 2.18] | 1.72 [1.04 - 2.86] | 0.013 |

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| History of musculoskeletal disorders in the family members | |||

| Yes | 2.42 [0.54 - 4.24] | 2.75 [1.14 - 6.64] | 0.035 |

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Marriage arrangement by | |||

| Parents | 10.22 [9.75 - 17.25] | 12.97 [9.75 - 17.25] | < 0.001 |

| Others | Ref | Ref |

5. Discussion

This research emphasized the significant occurrence of consanguinity, specifically the practice of first-cousin marriage, among married couples residing in the southeastern region of Iran. Consanguineous marriage is a long-standing tradition and a preferred marriage pattern in Iran, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 38% (17). However, major differences in consanguineous marriage rates between different provinces have been observed. For instance, the consanguineous union rates in Gilan, Tehran, Isfahan, and Yazd provinces were found to be 20.9%, 34%, 44.2%, and 50.2%, respectively (16). Consanguineous marriage rates of up to 74.3% have also been reported in the genetic counseling centers of Isfahan (24). Sistan and Balouchestan Province is recognized as one of the provinces with high rates of consanguineous unions, with reports of marriage to biological relatives reaching up to 78% (25). However, in contrast to prior research, we identified a reduced prevalence of consanguineous marriage (46.7%) within the study cohort, although it remains one of the highest rates nationwide.

The findings of our study indicated that the kinship structure among married couples closely resembled that of their parental kinship. Parental consanguinity has been proven to be a major predictor of the occurrence of consanguineous unions in the progeny, reflecting the effect of familial customs and parental beliefs (13, 17, 26). The process of consanguineous marriage is largely influenced by ethnicity, province, and area of residence (25). As a result of some traditions, the pressure or insistence of parents and other family members may lead to higher consanguineous marriage rates (27).

Significant variations in the occurrence and types of consanguinity have been noted among different ethnic groups in Iran, with rates ranging from 31.1% in the Lur ethnic group to 50% in the Balouch population (17). We observed relatively higher rates of consanguineous marriage among Balouch (47.2%) and Sistani (49.8%) couples living in southeast Iran. Additionally, various research findings have indicated that the prevalence of consanguineous unions can significantly differ among religious communities belonging to the same ethnic background. For example, when comparing Shi'a individuals to Persian and Kurdish Sunni populations, a higher percentage of consanguineous unions has been observed among the latter groups (52.1% versus 30% for Persian, and 40.1% versus 35.9% for Kurdish) (17). This is in agreement with our study findings, which showed that individuals from the Balouch ethnic background and some Sistani individuals, with the majority belonging to the Sunni religious group, have a high rate of consanguineous marriage. However, it should be noted that consanguineous marriage is not encouraged in the Islamic context, as it is primarily driven by social motivations and influenced by traditions and cultural beliefs (28).

Consanguineous marriage in our research was linked to various socio-demographic factors of the participants, such as age, level of education, income, and place of residence. This aligns with findings from different epidemiological studies on the factors associated with consanguineous marriages. Consanguineous unions have been found to occur more frequently in rural settings (17, 26). Although the choice of this type of marriage is influenced by socio-economic factors, the extent of the relationship varies significantly depending on the study design and setting (10, 15). For example, a study conducted in Tabriz, Iran, demonstrated a significant association between consanguineous marriage and factors such as age at marriage and level of knowledge (29). However, the occupation of the father, income level, and the degree of consanguinity among parents were significant factors influencing consanguineous unions in males, while no such association was observed in females. The findings of separate research conducted in Turkey indicated that mothers with higher educational attainment and families with two or fewer children exhibited reduced rates of consanguineous marriages (27).

One of the important strengths of this study was a response rate of 100% from all the couples who were approached to participate. We also used a semi-structured questionnaire for data collection during face-to-face interviews, which improved the quality of data collected. However, there are a number of limitations to the present study. First, this study was based on data collected from a single Pre-Marriage Counselling Center in Zahedan city. However, it is legally required in Iran for all couples to undergo a beta-Thalassemia trait screening prior to marriage and to attend a pre-marriage counseling center before completing the legal formalities of marriage (29). Hence, the study sample may be considered a reliable representation of the target population. Additionally, the residents of Sistan and Baluchestan Province are from the Sistani and Baluch ethnic backgrounds, sharing common cultural values and traditions. Therefore, the results of this study can provide valuable information about the prevalence of consanguineous marriages in this region. Second, in this study, the potential confounders such as socio-demographic characteristics of the participants and their parents, the consanguinity status of the parents, and the history of congenital malformations and genetic disorders in family members have been addressed by fitting a multivariable logistic regression model to the data. Nonetheless, it is impossible to completely rule out the chance of residual confounding brought on by unidentified confounders. Third, the total population of Zahedan district is 889,405, with 84% residing in urban areas and 16% in rural areas. Due to the utilization of a convenient sampling method for recruiting couples, the study slightly overrepresented the rural population (26% rural versus 74% urban). Nonetheless, the authors believe that these limitations do not diminish the credibility of the findings from this study.

In conclusion, consanguinity is a common social practice in the southeastern region of Iran, particularly among individuals with Balouch and Sistani backgrounds. Public health interventions are needed to increase public awareness of the prevention of the detrimental effects of consanguineous marriages. Additionally, efforts should be made to identify families at a heightened risk of genetic disorders and offer premarital genetic counseling within this community.