1. Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic Gram-negative bacterium, which is responsible for systemic infections among immunocompromised patients (1). This organism poses a growing public health concern worldwide. A recent report from the National Healthcare Safety Network introduced Pseudomonas aeruginosa as the sixth most typical nosocomial pathogen globally and the second most typical organism in ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in the United States hospitals (2). Also, patients enduring burn trauma are particularly susceptible to P. aeruginosa infection; therefore, this group is a major target for treatment (3, 4).

Carbapenems are the last line treatment for serious P. aeruginosa infections (5). However, in recent years, due to the widespread use of antimicrobial agents, carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa has dramatically increased (6, 7). Unfortunately, raising carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPA) is the leading cause of high mortality, prolonged hospital stay, and increased costs (3, 8). Since multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa is usually resistant to many classes of antimicrobial agents, the treatment regimens against these strains are limited (9).

Furthermore, finding a new therapeutic method for the treatment of such isolates is necessary. In the past, Papaver somniferum was considered as an antibacterial agent in traditional medicine. Opium (or poppy tears) is a dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of Papaver somniferum (10). Previous studies have proven the antibacterial effect of opium (11).

2. Objectives

Since limited studies have explored the effect of opium on P. aeruginosa and due to the lack of enough information about opium effects on carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, we decided to design this study to explore the influence of opium on carbapenem-resistant and carbapenem-sensitive P. aeruginosa.

3. Methods

3.1. Microbial Strains

During the study period from December 2018 to March 2019, we collected a total of 20 non-duplicate (one per patient) P. aeruginosa, including 10 meropenem-resistant and 10 meropenem-susceptible isolates. These isolates were randomly selected from clinical samples at Shahid Mohammadi and Pediatrics hospitals affiliated to Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences in Bandar Abbas, the South of Iran. Random numbers were computer-generated to select samples using the laboratory submission numbers. The random selection process was repeated until the target number was obtained. The isolates were identified as P. aeruginosa using phenotypic microbiology tests (12) and verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers of the gyrB gene for P. aeruginosa (13).

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

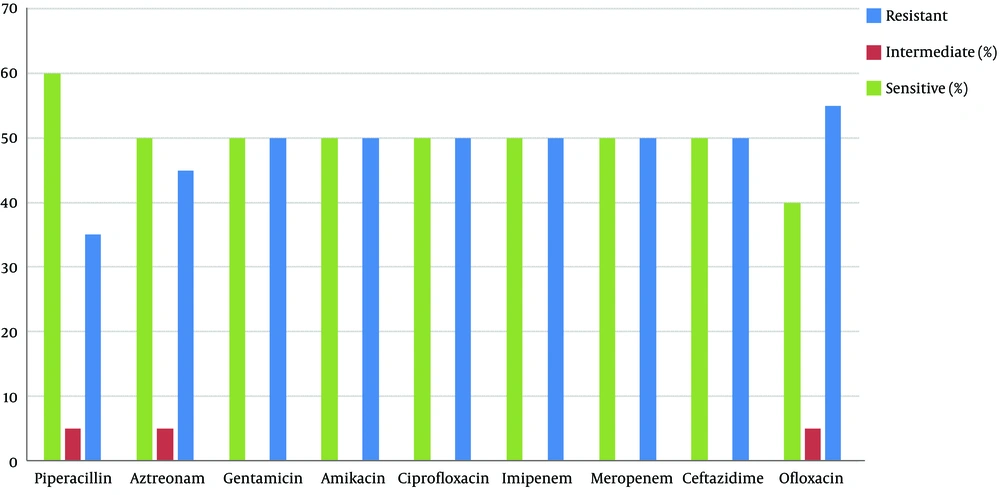

The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern was tested by disc diffusion according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. The following antimicrobial agents were used: meropenem (10 µg), imipenem (10 µg), piperacillin (100 µg), amikacin (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), ofloxacin (5 µg), aztreonam (30 µg), and gentamicin (10 µg). The plates were incubated in ambient air at 35°C for 18 h. All antimicrobial agents were purchased from Mast Company (MAST Group Ltd, Merseyside, UK) and the results were interpreted as sensitive, intermediate or resistant following the CLSI guidelines and the manufacturer protocols. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used for quality control (14).

3.3. Antimicrobial Screening Test of Opium

3.3.1. Broth Microdilution Studies

Broth microdilution was carried out in duplicate for the determination of MIC and MBC of opium. Briefly, a 100 mg/mL stock solution was prepared by dissolving opium in distilled water (opium was prepared as a gift from Faranshimi Co., Iran).

According to the CLSI guidelines (15), various concentrations of opium ranging from 4 µg/mL to 2,048 µg/mL were prepared in Mueller-Hinton broth (Merck, Germany) with a disposable 96-well microdilution plate (16). The bacterial suspension was prepared by the direct colony suspension method according to the CLSI guidelines (17). The plates were incubated in ambient air at 35°C for 20 h and then visually examined. Any turbidity was considered as the growth of bacteria. Additionally, 10 µL of each turbid well was cultured on the Mueller-Hinton agar plate to rule out the contamination and confirm that the growth was due to the tested organism. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used for quality control. One well with Mueller-Hinton broth alone was kept for sterility control.

3.3.2. Disc Diffusion Assay

Using a cotton swab, a 0.5 McFarland bacterial suspension was inoculated on a freshly prepared Mueller-Hinton agar plate (Merck, Germany). Five blank discs were placed and 10 µL of opium with concentrations of 32, 64, 128, 512, and 1,024 µg/mL were added to each disc following the CLSI guidelines (14). The plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h. The diameters of the zones of inhibition appearing around the discs were measured to the nearest millimeter (mm) and the results were compared with those of meropenem for meropenem-susceptible strains and ceftazidime or ciprofloxacin for meropenem-resistant strains. Any zone of inhibition around an opium disc indicated antibacterial activity and it was interpreted as positive results. For comparison, the full meropenem Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used for quality control (14).

4. Results

4.1. Bacterial Strains

A total of 20 Pseudomonas aeruginosa-positive isolates were recovered from the wound (30%), urine (30%), discharge (15%), blood (10%), the tracheal tube (10%) and other specimens (5%).

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

The results of the antimicrobial susceptibility test are shown in Figure 1. According to the results, the highest and lowest rates of resistance were to ofloxacin and piperacillin, respectively, and this drug had effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates.

4.3. Broth Microdilution Studies

The antimicrobial activities of opium were studied at different concentrations against 10 meropenem-resistant isolates, 10 meropenem-susceptible isolates, and standard (ATCC 27853) isolate. Unexpectedly, all clinical and standard strains of P. aeruginosa were resistant to opium, and all of the wells containing different concentrations of opium were turbid after 20 h incubation. The growth did not belong to contamination because pure P. aeruginosa strain was isolated from turbid wells by culture on the Mueller-Hinton agar plate.

4.4. Disc Diffusion Assay

The results of the disc diffusion assay showed that opium was ineffective against both clinical isolates and standard strains by disc diffusion.

5. Discussion

The present study was designed to determine the effect of opium on carbapenem-resistant and carbapenem-sensitive P. aeruginosa and the results of this study did not exhibit any significant increase in the sensitivity to all of the wells containing different concentrations of opium. Little is known about combination therapy for the treatment of P. aeruginosa infections and related evidence is not clear (16). At present, the fecal microbiota and phage therapy are opportunities available to combat antibiotic resistance.

Recent plans for therapy and diagnosis cannot stop the evolution of chronic infections observed in most adult patients (18). Common antibiotic therapy plans are just moderately efficient and may lead to drug resistance in bacteria and cause many side effects and clinical problems in patients (18). Some new antimicrobial compounds derived from plants and other living organisms have been proposed to avoid some of these resistance procedures (10). Ceftolozane-tazobactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, imipenem-cilastatin/relebactam and cefiderocol may supply action in the contradiction of MDR types of Pseudomonas. Some available articles explain the medical and microbiological efficiency of neoteric antimicrobials although emerging resistance demonstrates the continuous treatment face of Pseudomonas (19).

The antibacterial basis of opium is poorly understood and very little is currently known about it. Mami et al. (11) showed that opium had an antibacterial effect. Their results differed from the findings presented here. In contrast to our study, the antimicrobial effects of opiates were exhibited in different investigations (20). Antifungal and antibacterial effects of morphine and bupivacaine have been reported. These opiates had in vitro dose-dependent antibacterial effects on examined bacteria. Their experimental conditions showed that morphine and bupivacaine were effective at high doses and it was stated that this phenomenon was related to interaction with bacterial membranes (15). In concordance with our findings, Mami et al. (11) showed that P. aeruginosa isolates were resistant to opiates such as lidocaine and procaine. Also, the MIC results of their study revealed that some Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli and P. mirabilis, were sensitive to opium solution. It suggests that different sensitivities to various opium concentrations observed for these pathogens were probably due to different cellular structures (differences in the arrangement of fatty acids, proteins, and other cell wall and membrane components) (10). According to a study conducted by Rios and Recio (21), some general considerations must be established for the study of antimicrobial activity of plant extracts and the compounds isolated from them. Scientific criteria should be standardized and used in the study of plant material.

5.1. Conclusions

Although based on our observations, null antimicrobial effects of opium were found in tested isolates, studies of opium have to be continued, as it may show some bacteriostatic or bactericide activity in other conditions. It is not possible to absolutely declare that there is no possibility to suggest it as a traditional antimicrobial agent. Future studies with a larger sample size are needed to confirm our findings and evaluate opium in combination with herbal extracts to show its antibacterial effects.