1. Background

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) (1) can be related to an increased risk of health consequences (2). Long-term health consequences may include urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginosis, increased risks of obstetric consequences, obstruction of urine and menstrual blood, and sexual problems (2-4). However, because FGM/C involves a wide range of different practices, ranging from the pricking of the clitoris to full infibulation (5), health consequences may be largely related to how a practice is performed and what is done (6-8). FGM/C may cause obstetric, gynecological, and psychological (including sexual function) complications (9-11). Although FGM/C may give rise to negative physical, sexual, and psychological health complications, less is known about treatment and healthcare for women and girls living with FGM/C.

Sweden is a country in which the principle of equal access and quality in healthcare for all is strong. The healthcare system is obliged not to discriminate individuals and groups based on gender and ethnicity but provides all residents with equal opportunities to receive high-quality healthcare. However, some groups such as FGM/C-affected women and girls may have different healthcare needs than the majority of the population; thus may require specialized healthcare. It is estimated that 40,000 women and girls who live in Sweden had been subjected to FGM/C. They mostly have their origins from African or Asian countries and have already been subjected to FGM/C before migrating to Sweden.

An investigation (11) has been done to map the healthcare for women and girls who have undergone FGM/C.

2. Objectives

The aim of this brief report was to introduce innovations in healthcare and treatment of women and girls who have suffered from any form of FGM/C in order to improve our knowledge and understanding on the adoption, implementation, and potential scale-up of healthcare services and innovative policy cares for this target group in Iran.

3. Methods

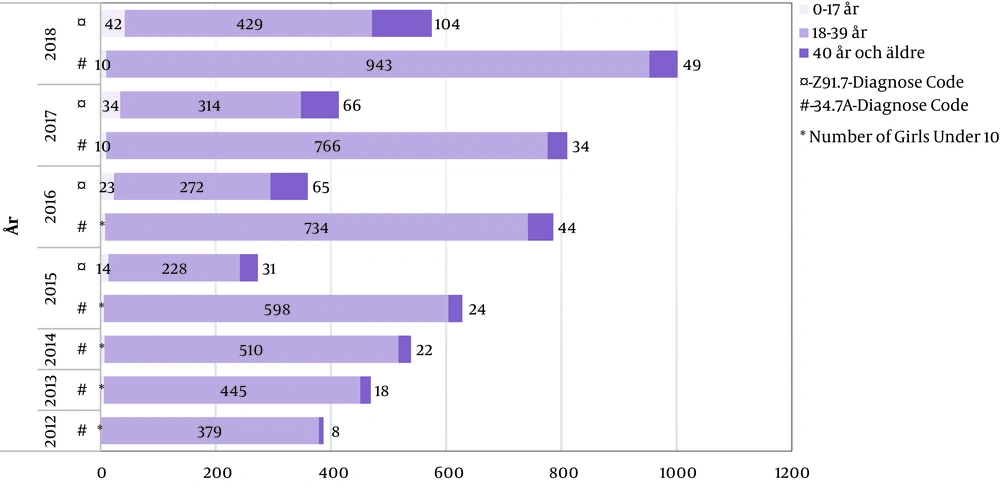

This study was conducted to survey the number of women and girls who were exposed to FGM/C and sought care during 2012 - 2018 and also what type of care measure they have been offered. Data on healthcare consumption in Sweden related to FGM/C were obtained from the patients register and the medical birth register. Two codes related to FGM/C were used as the main or bi-diagnosis factor in ICD-10-SE:

3.1. O34.7A

Care of future mother for vulva and perineum abnormalities in the form of previous genital mutilation.

3.2. Z 91.7

Female genital mutilation in medical history. This code was introduced by WHO on January 1, 2015.

An inventory of regional guidelines was conducted in Sweden to get a picture of the current state of knowledge about care measures for women and girls who have experienced FGM/C. The basis for the inventory of the regional guidelines has been collected via e-mail contact with regional coordinators.

The literature review was carried out. The specific objectives were to investigate existing care measures and treatment alternatives for FGM/C-related complications, the healthcare professionals’ perceptions and experiences of providing care to this target group and also health-seeking behaviors among the target group. The inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed original qualitative and quantitative research articles and literature reviews relevant to the study objectives published in the English language from 2000 - 2019. The quality of included articles was assessed using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research tool (12).

4. Results and Discussion

The care offered in Sweden today varies can be categorized as obstetric care, gynecological care, consulting, vulva plastic surgery, and other vulva or perineum reconstruction. The results showed that there were about 5,000 women and girls diagnosed with FGM/C who have sought care between 2012 and 2018. They mostly sought care and offered care in connection to pregnancy and childbirth. The number of girls and women who have been exposed to FGM/C and sought care and received a diagnosis is lower among girls under 18 and women over 40 (Figure 1). This may indicate that these age groups do not need care, do not have access to or information about care, and do not dare to seek care or do not want to seek care for fear of being stigmatized by their own family/community or society.

There are two specialist medical centers with healthcare providers (HCP) who have the experience of FGM/C in Sweden. Female gynecologists, midwives, and curators work at these receptions. The centers use a female professional interpreter when needed. The following care measures were included in their treatment: sexual consultation, the usual gynecological examination, opening surgery if needed, surgery regarding delivery injuries, clitoris reconstruction (CR), and removal of cysts.

The inventory of the region guidelines on care for women and girls diagnosed with FGM/C showed that most of the 21 regions have regional or local governance guidelines.

The literature review showed most studies investigating healthcare interventions for FGM/C-diagnosed women encompass surgeries such as defibulation, CR, and removal of cysts. CR is a type of surgical intervention that has the potential to improve FGM/C diagnosed women’s and girls’ health, particularly regarding sexuality, body image, and self-confidence (13). Removal of cysts is another type of surgical intervention. Berg et al. (14) discussed the improvement of women’s sexual lives, no intraoperative complications, good recovery, and no reoccurrence of cysts one to six years post-surgery.

The literature review demonstrated that there are issues in care encounters that affect both HCPs and FGM/C diagnosed women and girls negatively. One aspect is HCPs lack knowledge on FGM/C as well as express negative emotions about it. The silence that existed around FGM in care encounters seemed to increase discomfort in both women and HCPs, which lead to reduced chances of exchanging information about needs and fears. Another important aspect identified in the review was the lack of care pathways or clarity in the care continuum, lack of guidelines, procedures, and implemented routines about what to do with girls and women exposed to FGM/C in healthcare services.

FGM/C violates girls’ and women’s human rights, which are enshrined in the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” and the “convention on the rights of the child”. Although Iran is a signatory to both still violence in the form of practicing FGM/C, it continues to be a risk for women, especially girls in various provinces (15). According to previous research, the prevalence of FGM/C in Iran is high in seven provinces, namely Hormozgan, Bushehr, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, Khuzestan, Lorestan, and West Azerbaijan (16-20). One study demonstrates that the prevalence of FGM/C is approximately 60% in the rural areas around Hormozgan and 42% in villages around Marivan (16). The prevalence of FGM/C in Ravansar is about 55.7%. Most of the girls exposed to FGM/C before they become seven years old by traditional circumcisers (17). A study in Minab estimated the prevalence of FGM/C around 70%. It was also shown that they performed type I (21) to a greater extent (87.4%) than type II (22) (12.6%) (20). This practice has been performed confidentially in families and there are no official statistics about it. There is a silence in the families and in the society about FGM/C. Reasons for performing FGM/C in Iran like in any other part of the world are to control girls’ sexual activities, preserving “virginity”, and protecting against pre-marital sexual activity. The cause of practicing FGM/C in these provinces can be due to a combination of socioeconomic, religious, and cultural factors. In provinces that FGM/C is a norm, if girls do not conform to that, they will be stigmatized, marginalized, and demoted.

Iran has accepted the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. FGM/C has been considered as a disability, and the practice of it should be stopped. The studies conducted on FGM/C in Iran are few, and most of them discussed knowledge, attitude, prevalence, and types of FGM/C as well as legal and judicial aspects. There are no studies and on public health policies about how to deal with FGM/C (23) or how healthcare treat and provide care for this target group. One study on health sector involvement in the management of FGM/C among 30 countries (24) shows that Iran has no national policies on FGM/C. Healthcare providers do not receive training on FGM/C and have no duties to health-educated patients and report FGM/C. It also shows that there is no legal regulation on FGM/C at the national

level and it is not illegal for HCPs to perform FGM/C. There are no medical services available for Iranian girls and women exposed to FGM/C. The study shows that in Iran there are no diagnosis codes on FGM/C available to be used systematically in medical records.

Based on the Swedish experience and WHO guidelines, what can be suggested for better care of women and girls subjected to FGM/C in Iran are as follows:

To break the silence and talk aloud about FGM/C and its health consequences;

To improve the public knowledge regarding FGM/C and its health consequences;

To collaborate with schools and provide education regarding FGM/C and its health consequences for school staff but also parents and pupils;

To encourage and support girls and women subjected to FGM/C to seek healthcare;

To provide web education for local/province HCPs regarding health consequences of FGM/C and different ways of care for the target group by for example research center in the Health Ministry;

To prepare guidelines at region, province, and country level for stopping FGM/C and provide healthcare to girls and women who suffers from it;

To educate HCP that can understand and work with this target group;

To use the diagnose codes ICD-10-SE: O34.7A and Z 91.7 in healthcare system in order to register, map, and follow up these patients;

To offer healthcare in the form of surgery or psychosexual consulting to the target group;

To offer culturally sensitive and person-centered care to the target group;

To establish specialist medical centers with HCPs who have experience of FGM/C, in those provinces that FGM/C has a high prevalence;

As poverty, low education and patriarchal culture are the main reasons for FGM/C practice there is an enormous need to work to eliminate these reasons. The elimination of these components may assist to remove the cultural and traditional barriers.

To conduct more research on healthcare policies and services for women and girls experienced FGM/C in Iran.