1. Introduction

Xeroderma pigmentosum XP was first reported in 1874 by Hebra and Kaposi (cited by English and Swerdlow) (1). People with XD are extremely sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight that leads to defective DNA repair mechanism (2). Depending on the affected genes, there are seven types of XD, which each has a different prevalence and severity. XPA is the most common type (3). XP, inherited as an autosomal recessive pattern, has an equal frequency in male and female patients and occurs in all races. Its incidence ranges from 1 in 250,000 in the USA (4), 1 in 20,000 in Japan, to 2.3 per million live births in Western Europe (5). Its symptoms are photosensitivity, dry skin, changes of skin pigmentation; corneal keratitis, conjunctivitis and lid ulcer, premature skin aging, and a significant increase in incidence rates of skin cancers (6, 7). The estimated risks of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer and melanoma skin cancer are 10,000 and 2000 times higher, respectively, in people under age twenty (8). Malignant skin tumors in XP patients include melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma (9). As there is no cure for XP, prevention, and early diagnosis play a critical role in managing the disease. Besides, regular follow-up is the key to managing symptoms. In this article, we have described four children from two families diagnosed with XP, three of whom had skin cancer. It worth noting that the images of patients were taken with the informed consent of the parents.

2. Case Presentation

Patient 1 was a 6-years-old boy (Figure 1), the first offspring of a consanguineous marriage. He was from a family of low socioeconomic status. His parents were healthy, and he had no developmental or neurological disorders. Freckles and pigmentary skin changes occurred gradually at the age of about 18 months. Physical examination showed involvement of the face, eyes, lips, and the neck demonstrated as hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules, dry skin, and keratotic skin lesions. He suffered from conjunctivitis, extreme sensitivity to sunlight, and decreased visual acuity. His parents noticed a nodular lesion in his neck about 3 months earlier. The boy underwent complete excision of the lesion, and the histopathological findings indicated malignant melanoma. Adjuvant therapy was administered with interferon alpha-2b. Other diagnostic tests revealed no evidence of distant metastasis, and the patient is now alive.

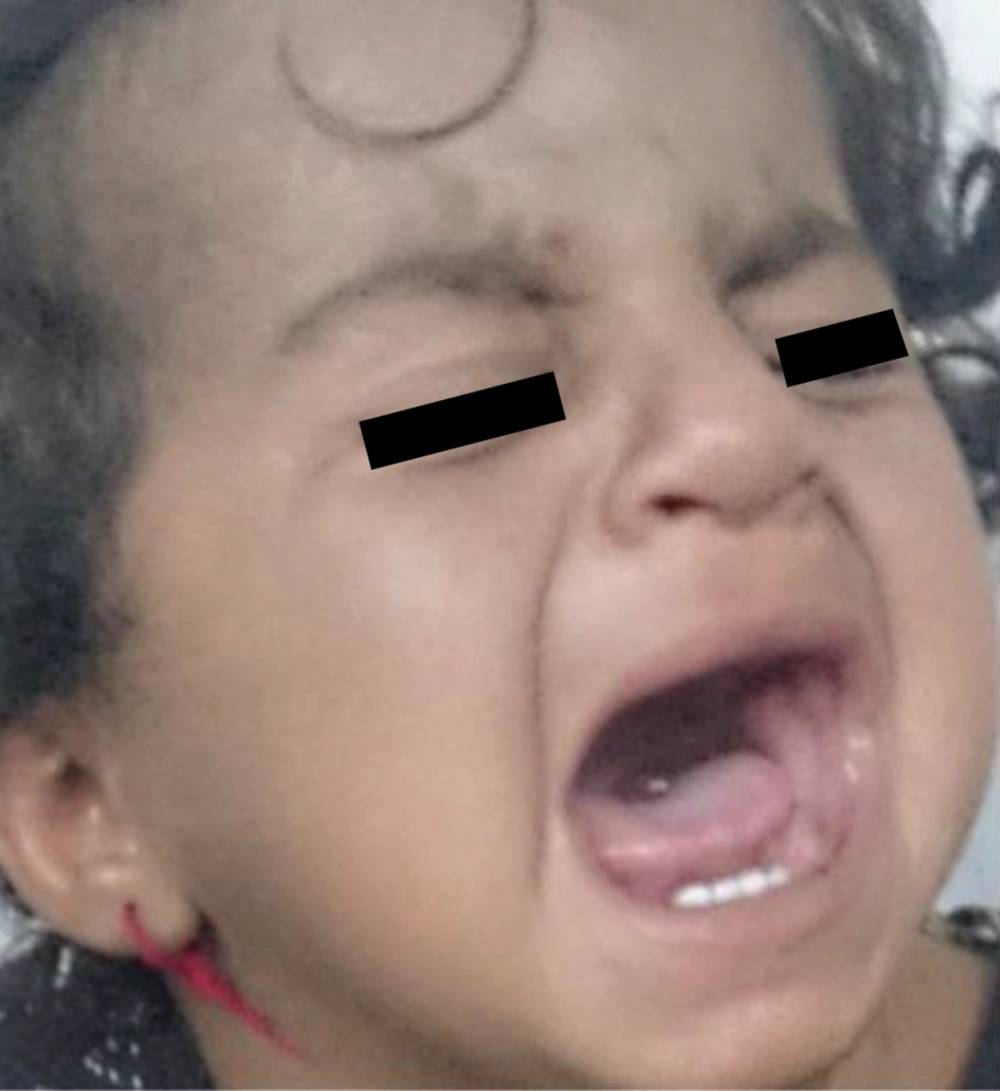

Patient 2 was a 2-years-old girl (Figure 2) and the third offspring of a consanguineous marriage. She was the sister of the patient number one and had normal growth and development. She developed hyperpigmentation and freckles, and pigmentary skin changes on her face and neck when she was about 1-year-old. However, the lesions were much less severe than those of her brother. Fortunately, she did not have any lesions suspected of malignancy. Sun protective measures, such as hats, sunglasses, face shields, sunscreen lotions, and avoidance of sun exposure, were educated to the parents.

Patient 3 was a 10-year-old boy (Figure 3), the second offspring of a consanguineous marriage. He developed photosensitivity, conjunctivitis, and pigmentary changes of the skin on the head, face, neck, and hands. He developed squamous cell carcinoma of the left nasolabial fold at age 8 years, and surgical excision of the lesion was performed. He was not suffering from developmental or neurological disorders. He is now alive and has no signs of recurrence or metastasis.

Patient 4 was a 12-years-old girl (Figure 4), the first offspring of a consanguineous marriage. She was the sister of the patient number 3. Her neurological examinations were normal. She developed photophobia, decreased visual acuity, hyperpigmentation, and freckle-like lesions on her face and forehead when she was about 18 months old and nodular lesions on the forehead and on the tip of the nose at age 8 years. Biopsy revealed squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma in the mentioned areas, respectively, and the girl underwent complete removal of the lesions. She is now alive with no evidence of new skin cancer.

3. Discussion

XP is a rare inherited disorder characterized by excessive photosensitivity in which pigmentary changes of the skin occur with minimal sun exposure that causes increased susceptibility to developing skin cancer (3).

Bradford PT et al. (8) showed that the risks of nonmelanoma skin cancer and malignant melanoma in patients with XP were more than 10,000 and 2000 times higher, respectively, in XP patients younger than 20 years of age. These young XP patients developed their first nonmelanoma skin cancer and melanoma 58 and 33 years earlier, respectively, compared to the mean age of XP patients, and the most common causes of death among them were metastatic melanoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma (8). In fact, defect in the DNA repair mechanism has a major role in the etiology of skin cancers and neurological degeneration as well as morbidity and mortality in these patients (8).

As in other genetic disorders, genetic counseling and psychological support should be provided to families about the XP. Necessary information about XP should be provided to the families as well as the increased risk of these patients for developing skin cancers and prenatal diagnosis of XP (5).

The current study had limitations, including the low number of patients. As there is no cure for XP, prevention and early diagnosis play a critical role in managing the disease and controlling the symptoms. Besides, regular follow-up by a dermatologist and/or ophthalmologist is crucial for in time identification of malignant lesions. Early and timely diagnosis, application of stringent sun-protection using special eyeglasses and sunscreen creams, and avoiding sun are important measures for preventing skin cancer as well as improving both quality of and life expectancy of XP patients. In the absence of neurological disorders and in cases with early identification, the prognosis of XP is good. However, protecting against sunlight and UV radiation are of crucial importance. Prenatal diagnosis is recommended if available. The authors suggest performing further studies on the XP epidermal stem cell and DNA repair.