1. Background

Breast pain, also known as mastalgia, mastodynia, or mammalgia, can be cyclical or non-cyclical, bilateral or unilateral, intermittent or continuous, and diffuse or focal. Mammalgia is one of the most typical breast complaints among women requiring medical attention (1) at breast clinics and imaging departments (2-4). According to some statistics, about 45 - 70% of breast-related symptoms in the primary care setting are associated with breast pain (5), and this type of pain is more common than breast cancer (6). Some reports have indicated that 50 - 80% of women experience mastalgia in their lifetime (7, 8).

Three types of breast pain are introduced: cyclical, non-cyclical, and extramammary (9). Cyclical mastalgia is associated with the menstrual cycle and usually occurs in both breasts diffusely. It is felt as soreness or heaviness at the breast and radiates to the axilla and arms (10, 11). It is more frequent in younger females and is resolved spontaneously. Non-cyclical mastalgia is not associated with the menstrual cycle. This type of pain can be persistent or intermittent. Extramammary pain arises from the chest wall but is felt within the breast (musculoskeletal chest pain). Some examples of extramammary pain are costochondritis, Tietze syndrome, and others (7, 9, 12). This type may be unilateral and localized in the breast, being observed more frequently in females aged 40 - 50 years. Extramammary pain is felt as a burning, sharp pain (10, 13).

Although breast pain, as the only symptom, is a low risk factor of breast cancer (9, 14), it leads to remarkable morbidity, anxiety and generally influences of the quality of life worldwide (15, 16). These women often seek medical attention due to concerns about possible breast cancer as the most typical female cancer worldwide (17-19). Studies have recommended imaging in patients who need reassurance (20).

In addition to clinical breast examination (CBE), imaging techniques such as sonomammography and mammography play a pivotal role in evaluating the painful breast, especially when there is a palpable mass. Sonomammography uses high-frequency sound waves above the human audible range (20 Hz - 20,000 Hz) to produce the images of the concerned area (3). This technique is highly acceptable for evaluating a dense breast, differentiating cystic from solid masses, and assessing highly painful breast in a patient who cannot withstand the compression involved with mammography examination. Mammography utilizes low-dose X-rays with breast compression to produce high-quality breast images revealing microcalcifications (21). In the absence of a palpable mass, the same tools are deployed to exclude an occult lesion in younger and older women, respectively, or to be used in combination (16).

Countries such as America, Europe, and Asia have had clinical trials and developed guidelines to help clinicians manage women with breast pain (15, 22). However, management schedules in African society are still in their infantile stage. On the other hand, imaging findings in women who present with breast pain in Southeast Nigeria have not been evaluated.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the diagnostic yield of mammography and sonomammography in women complaining of breast pain in a teaching hospital in Southeast Nigeria from January 2015 to December 2017.

3. Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of a Teaching Hospital affiliated with the University of Nigeria, Ituku/Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria.

We used a questionnaire to obtain biodata and past medical history of the subjects. Then, each subject signed the consent page in the questionnaire. Clinical breast examination was done, followed by breast imaging. The mammographic examination was performed using GE Alpha RT mammography machine, with a molybdenum cathode/target combination. Exposure factors were generally a low tube voltage ranging from 25 - 35 kVp and an mAs of 200. The mammographic images were acquired using film/screen combinations and stored physically with hardcopy reports in an archival room. Sonomammography was performed with a Toshiba ultrasound machine, with a linear transducer at frequencies ranging from 7.5 to 10 MHz, depending on the breast size. The images and reports were stored on a digital archive on a computer's hard drive, and the hard copies were stored in secure cardboard paper files.

A retrospective analysis was performed on breast imaging questionnaires and the mammographic and sonomammographic reports of 241 women with breast pain referring to the radiology department of our hospital during a three-years period from January 2015 to December 2017. A non-random sampling method was employed to select the participants. The following variables were extracted from the records, questionnaires, and radiologic reports: Patients’ age, positive clinical history of breast pain, laterality of breast pain, type of imaging, presence or absence of lesions, type and laterality of lesions if present, and Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) assignment of imaging findings on mammography and sonomammography.

Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Inc, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used for the descriptive analysis and display of the following variables: Frequency of breast pain amongst different age groups of the women, the laterality of symptoms, and the BI-RADS assignment of the lesions identified on either mammography or sonomammography amongst different age groups. Inferential statistics, including chi-squared test (GraphPad Prism, Version 5.03 (Graphpad Software Inc. USA, 1992-2010)), was used to compare the incidence of positive and negative imaging findings among the participants with unilateral and bilateral mastalgia. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

Two hundred and forty-one women referred to the radiology department with a complaint of breast pain, most (20%) of whom were in 40 - 44 years old range (Table 1). Moreover, 65.6% and 34.4% of the women had unilateral and bilateral breast pain, respectively (Table 1). According to the BI-RADS lexicon, 76.4% of the women with mastalgia, either unilateral or bilateral, ended up with BI-RADS 1, i.e., no mammographic/sonomammographic abnormality, and 21.9% had positive imaging findings (Table 2). These were predominantly benign breast masses such as fibroadenomata and cysts, mainly observed in the participants in the age group of 45 - 49 years. When lesions emerged, they were mostly benign-BI-RADS 2. Moreover, the higher grade BI-RADS (4 or 5) lesions occurred more in patients with unilateral mastalgia (Table 2). The lesions diagnosed in positive cases were simple fibroadenoma, breast cysts, fibrocystic breast disease, lactational and non-lactational breast abscesses, breast cancer, fat necrosis, mastitis, and Mondor’s disease. In this regard, 88% of women with bilateral mastalgia had negative/normal imaging findings (BI-RADS I). Chi-Square analysis revealed a P-value of 0.0089 (P < 0.05), thereby confirming that imaging the breasts of women with bilateral mastalgia will likely not yield any pathology (Table 3).

| Age Range (y) | Types of Examination | Breast Pain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography | Sonomammography | Total | Unilateral | Bilateral | Total | |

| < 20 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| 20 - 24 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| 25 - 29 | 1 | 30 | 31 | 18 | 13 | 31 |

| 30 - 34 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 16 |

| 35 - 39 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 27 | 5 | 32 |

| 40 - 44 | 33 | 16 | 49 | 32 | 17 | 49 |

| 45 - 49 | 23 | 11 | 34 | 19 | 15 | 34 |

| 50 - 54 | 23 | 6 | 29 | 19 | 10 | 29 |

| 55 - 59 | 9 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 14 |

| 60 - 64 | 11 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| > 64 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 118 | 123 | 241 | 158 (65.6%) | 83 (34.4%) | 241 |

| Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) Assignment | Unilateral Mastalgia | Bilateral Mastalgia | Sub-total | Interpretation | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI-RADS 0 | 4 (2.5) | 0 | 4 (1.7) | Inconclusive | 4 (1.7) |

| BI-RADS I | 111 (70.3) | 73 (88) | 184 (76.4) | Normal | 184(76.4) |

| BI-RADS II | 19 (12) | 10 (12) | 29 (12) | Benign | 42 (17.4) |

| BI-RADS III | 13 (8.2) | 0 | 13 (5.4) | ||

| BI-RADS IV | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | Malignant | 11 (4.5) |

| BI-RADS V | 9 (5.7) | 0 | 9 (3.7) | ||

| Total | 158 (100) | 83 (100) | 241 | 241(100) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

| Imaging Findings | Laterality of Mastalgia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral Mastalgia | Bilateral Mastalgia | Total | |

| Positive imaging findings | 47 (29.8) | 10 (12) | 57 |

| Negative imaging findings | 111 (70.2) | 73 (88) | 184 |

| Total | 158 (100) | 83 (100) | 241 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-square df = 9.439, 2. P = 0.0089 (P < 0.05)

5. Discussion

Breast pain seems to be more prevalent in the 5th decade of life among the research participants. The women complaining of breast pain mainly belonged to the age group of 40 - 49 years (n = 83, 34.4%). This finding agrees with those of some other studies in Ghana, the USA, and Australia, reporting mastalgia to be predominant among women passing their 5th decade of life (2, 3, 16, 23). In our study, painful breast masses were most reported in women aged 40 - 49 years (35% of all cases). Furthermore, 65.6% and 34.4% of the women had unilateral and bilateral mastalgia, respectively. This finding is similar to previous works suggesting relatively fewer women experiencing bilateral mastalgia (1, 3).

The preponderance of negative/normal findings on imaging in the present study agrees with some previous studies, especially those in the setting of a normal CBE (9, 17, 20). In this study, 76% of the patients revealed no abnormality on imaging, which is similar to two reports in the USA (77.3% and 75%) (16, 17). On the contrary, in some studies in Nigeria, smaller frequencies (4.7%) were reported (1, 2).

The etiology of mastalgia is not fully understood; however, some reports have demonstrated its association with anxiety, depression, psychosomatic disorders, and high-stress levels (24-26). Moreover, high levels of prolactin and high plasma fatty acids have been introduced as the possible causes of mastalgia, especially in the absence of clinical or radiological findings (27). Other factors associated with breast pain are caffeine and nicotine consumption, lactation frequency, alteration in estrogen/progesterone ratio, oral contraceptives, hormonal therapy, psychotropic drugs, and others (10, 14, 16, 28). Large breasts also cause some degree of ligamentous pain (9). In the aforementioned cases, negative/normal imaging findings are usually observed.

Our study shows that, a majority of the women with positive imaging findings (n = 42, 79.2%) had lesions with BI-RADS II and III assignment, suggesting that most of the patients with painful breast lesions had benign imaging attributes. This finding is some reports in local studies (71.4% (25 out of 35), 98.9% (841 out of 850) and 85% (57 out of 67)), clinically and histologically proving benign diseases in a majority of women presenting with mastalgia (1, 29, 30).

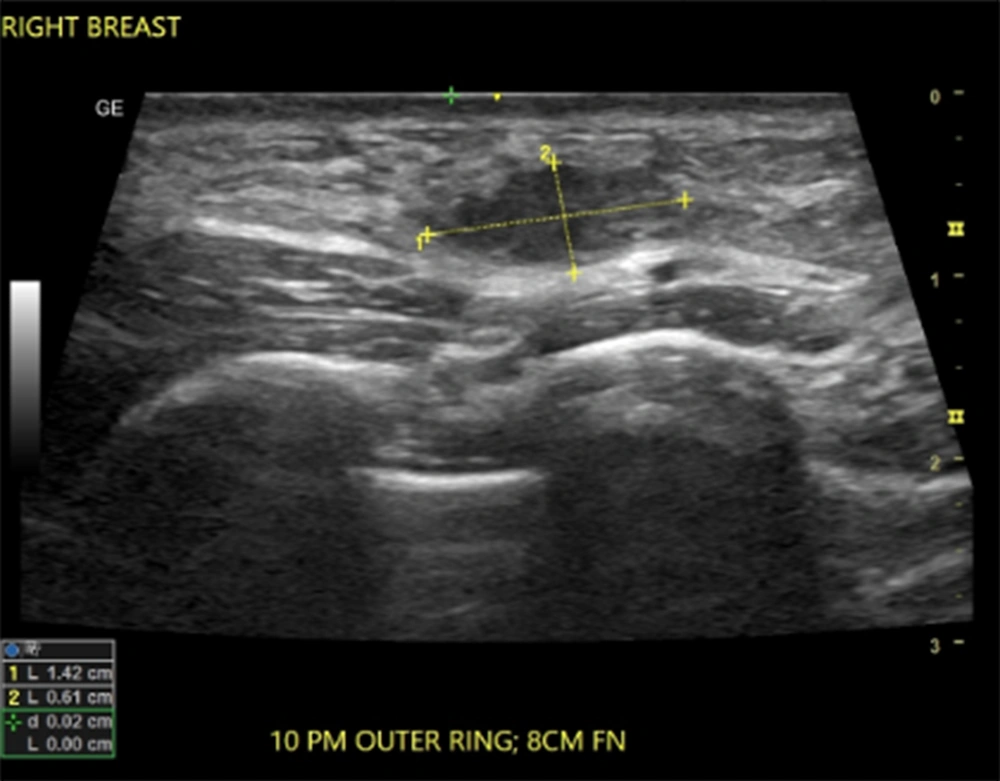

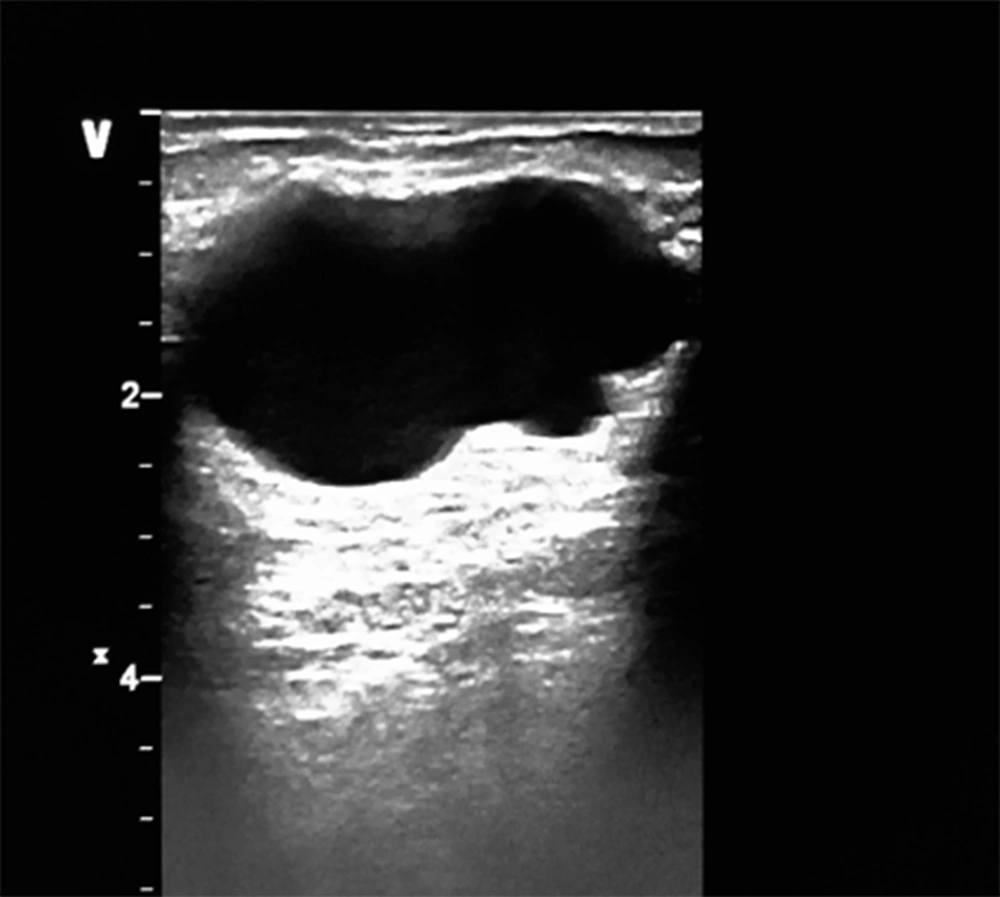

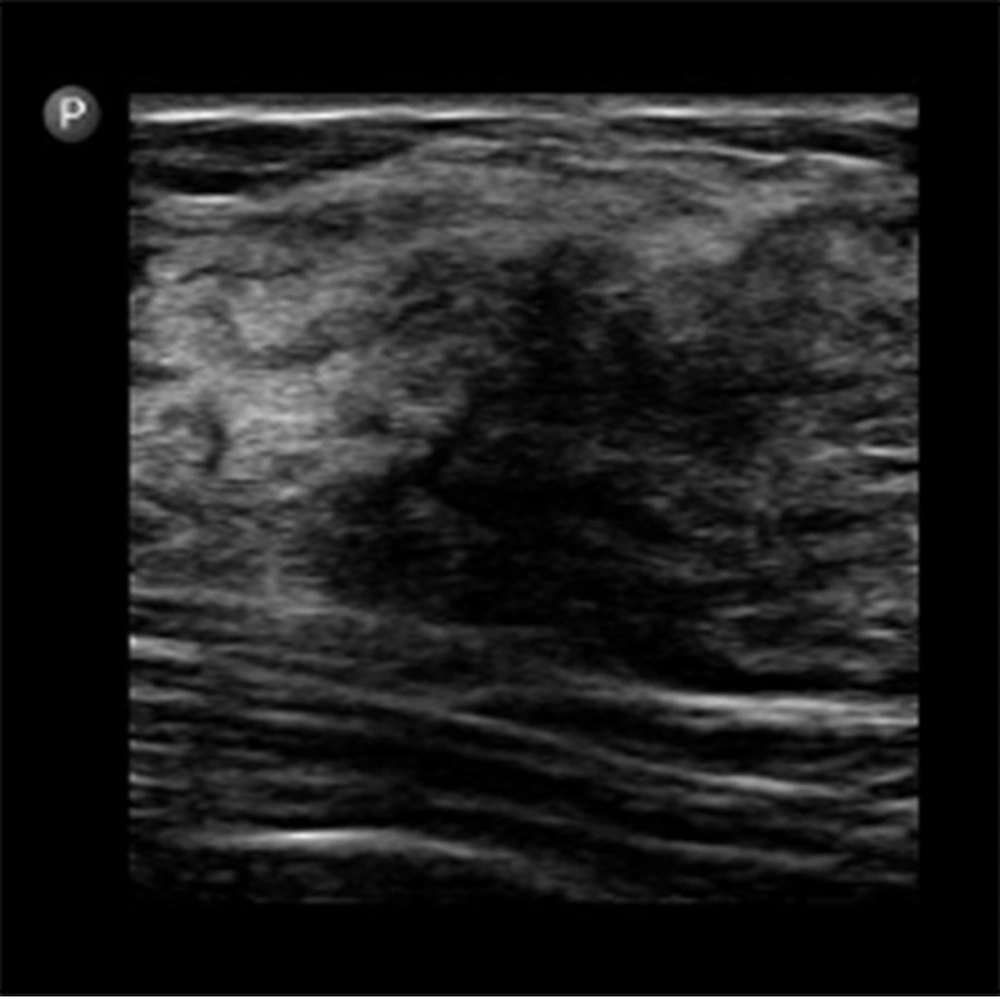

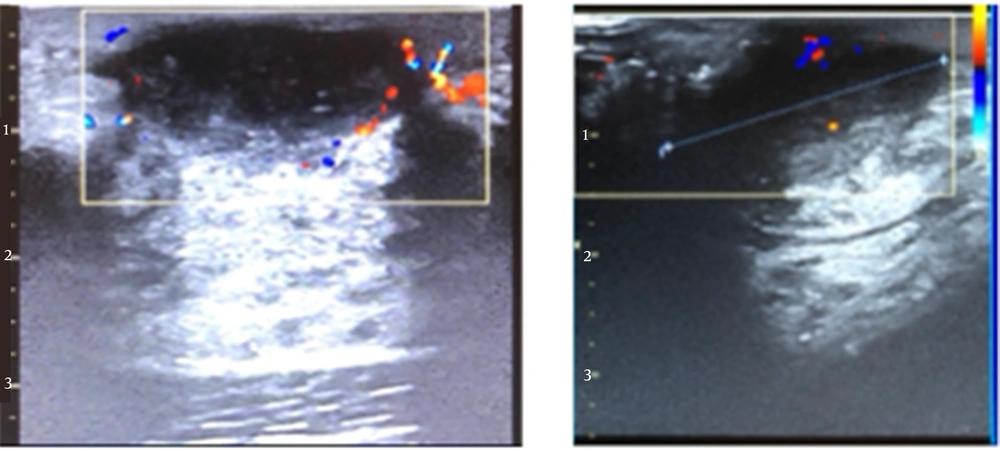

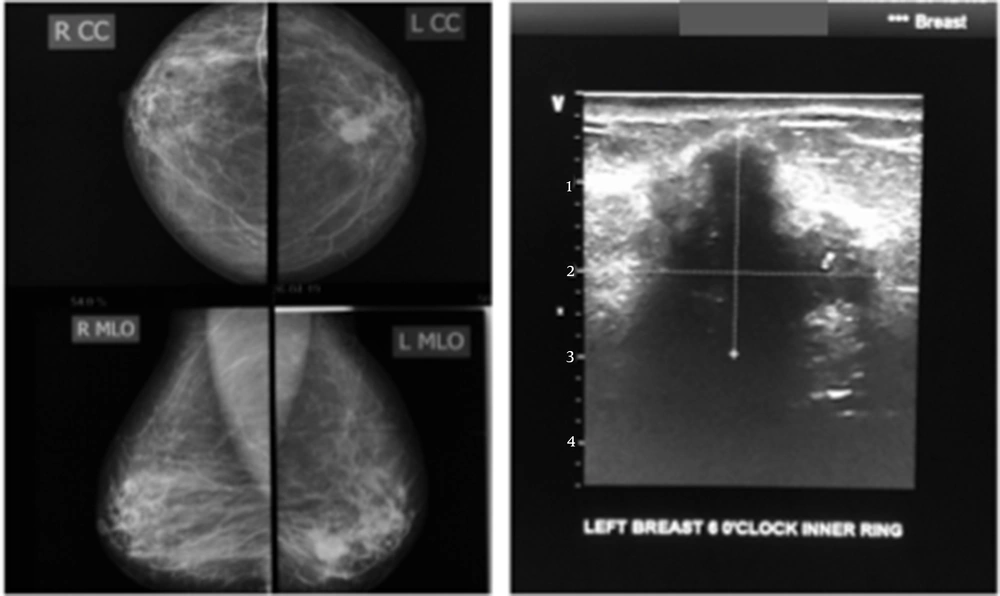

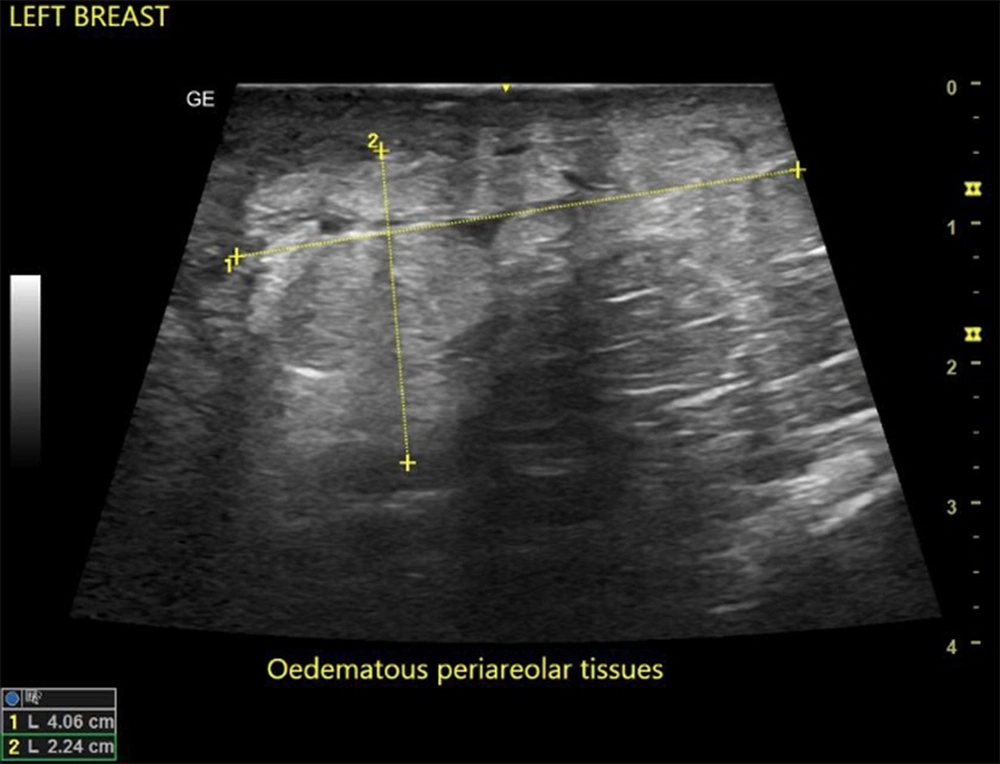

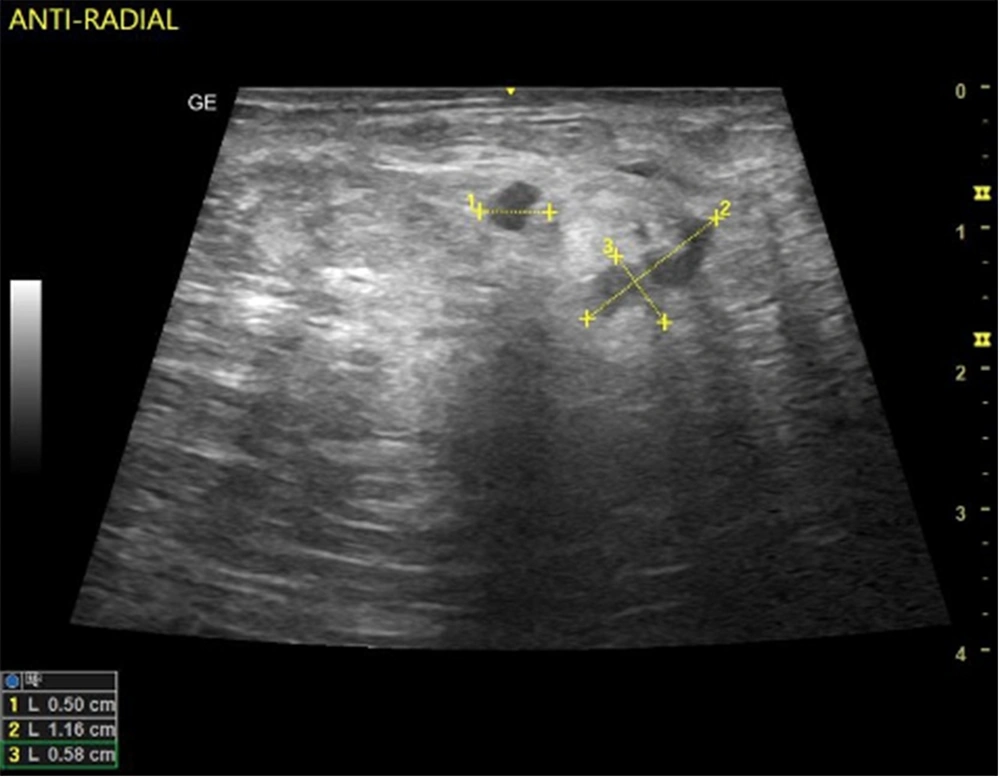

In this study, the predominant imaging diagnosis was fibroadenoma in those with lesions (Figure 1), followed by solitary or multiple simple breast cyst(s) (Figure 2), fibrocystic disease (Figure 3), lactating/nonlactating breast abscesses (Figures 4A and B), and cancer (Figure 5). This finding is in a similar vein with some studies (12, 16) and in contrast with some other studies claiming a fibrocystic change as the most common breast pathology in women with breast pain (1, 2, 29, 31, 32). Interestingly, we observed just one case with a sonological diagnosis of diffuse mastitis, which we assumed was tuberculous, but ended up with a histological diagnosis of breast myxoedema (Figure 6). One patient had a history and sonologic findings suggestive of fat necrosis, which was confirmed at histology after ultrasound-guided core biopsy (Figure 7).

The LCC and LMLO views of the mammogram (left) show an oval dense, bilobed mass with spiculated margins extending into the surrounding tissues; complimentary ultrasound (right) shows a deeply hypoechoic, taller-than-wide mass with irregular margins. Findings are consistent with malignancy. Histology confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma.

A case of fat necrosis; the patient presented with a painful right breast after sleeping on the bare floor the previous night. Ultrasound showed multifocal irregular hypoechoic foci on a background of echogenic (oedematous) breast tissue. The histology of the core needle biopsy revealed fat necrosis. The symptoms and ultrasound findings were resolved after three weeks.

Reports have also demonstrated a lower risk of breast cancer in women with breast pain, citing frequencies ranging from 0.4 to 0.6% (19, 29, 33). Nine women (3.7%) in our study had BI-RADS V assignments. In previous work on 110 subjects with the breast pain symptoms, no cancer was detected. This, however, may be due to the small sample size of the participants in this study (16). Nevertheless, researchers have demonstrated that cancer prevalence in breast pain ranges from as low as 0.6% and 1.5% (17, 20, 29) to as high as 28.6% (1). The higher frequency is most likely to be attributed to the absence of histopathological confirmation. The cited studies included histopathology outcomes and reported that women with other complaints other than breast pain are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than women with isolated breast pain (30).

No male with breast pain was observed in the present study. This is similar to the findings in Australia (3) and contrary to other studies reporting that 0.6% of the patients were male. It has to be noted, however, that the latter study included other breast complaints besides breast pain (2).

We believe that, despite the negative yields, imaging the painful breast is beneficial. Researchers have noted that the high negative predictive value (NPV) of mammography and sonomammography are quite reassuring not only for the patient but for the managing clinician, even in a setting of a normal CBE (20).

5.1. Conclusions

Imaging, including mammography, and sonomammography, helps confirm or rule out a cause for breast pain. More often than not, there are adverse findings on imaging. Of those that turn out positive, a large majority are benign lesions. Considering the low diagnostic (imaging) yield in patients with mastalgia, there is a need to properly examine and select patients who would likely benefit from imaging, especially those with other symptoms along with breast pain. However, in our environment, where there is still a poor culture of breast screening, this could serve as an opportunity to screen for cancer.

5.2. Limitations of Study

There was no distinction between different forms of breast pain-focal/diffuse and cyclical/non-cyclical as these specific types of pain tend to indicate certain pathologies. Furthermore, the histological diagnosis of the BI-RADS-assigned lesions was not performed for all cases. Moreover, the number of women with breast pain with or without a concomitant breast mass palpated on CBE was not determined.

5.3. Recommendations for Future Studies

Further studies on imaging findings should be followed up with histological diagnosis to reach more comprehensive findings.