1. Context

According to the official declaration of the 30th World Health Assembly in 1978 (the Almaty Declaration), the leading social goal of governments and the World Health Organization (WHO) should be to achieve a level of physical, mental, and social health for all people (1). Primary health care (PHC) was introduced as a method to achieve health for all (HFA) in 1978 (2). Achieving HFA must be accompanied by high-quality health services (3, 4). Also, the Astana Declaration is a recent milestone highlighting the quality of care at the PHC level (5). Quality of care is one of the most critical and global challenges facing health systems, especially at the PHC level (3, 6-8). The solemn responsibility of health policymakers and managers is the PHC quality assurance and improvement (9, 10). The quality of PHC is a priority in fragmented and pluralistic health systems, which are common in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) (11). In the past decades, quality has become a tool for improving the effectiveness of services, especially in developing countries, and extensive activities have been conducted to assess the quality of PHC (12).

Quality assessment is the first step in improving service quality (13). Because a multidisciplinary team provides the primary care (PC) services, quality assessment at the PHC level is more complicated (11, 14). The performance of each individual and the relationship between them and customers affect the overall PHC quality (11). International organizations such as WHO and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) encourage countries to assess the performance of their healthcare systems (2, 15). They have also presented frameworks for quality assessment in PHC (16).

One of the standard methods for assessing quality in PHC is the Quality Assessment Frameworks (QAFs), including quantitative indicators (17). Various reports have been published at national and international levels on PHCQAFs regarding multiple approaches based on their own needs, strategies, and objectives (18-21). Moreover, Australian Health Care Safety and Quality Commission has introduced seven dimensions of access, fitness, patient acceptance/participation, effectiveness, care coordination, and continuity of care safety as PHC quality dimensions (QDs), with 36 quality assessments indicators (QAIs) (22). However, the literature suggests that PHC processes and structures vary based on the context of each health system (23). Additionally, there are fundamental differences in quality assessment conception across countries (24, 25). Therefore, each country should develop a national framework for assessing the PHC quality by its own strategies and goals. Comparing PHCQAFs illustrates similarities and differences, indicates critical factors in the quality of PHC, and shows the neglected gaps and issues. This study aimed to compare the PHCQAFs.

2. Methods

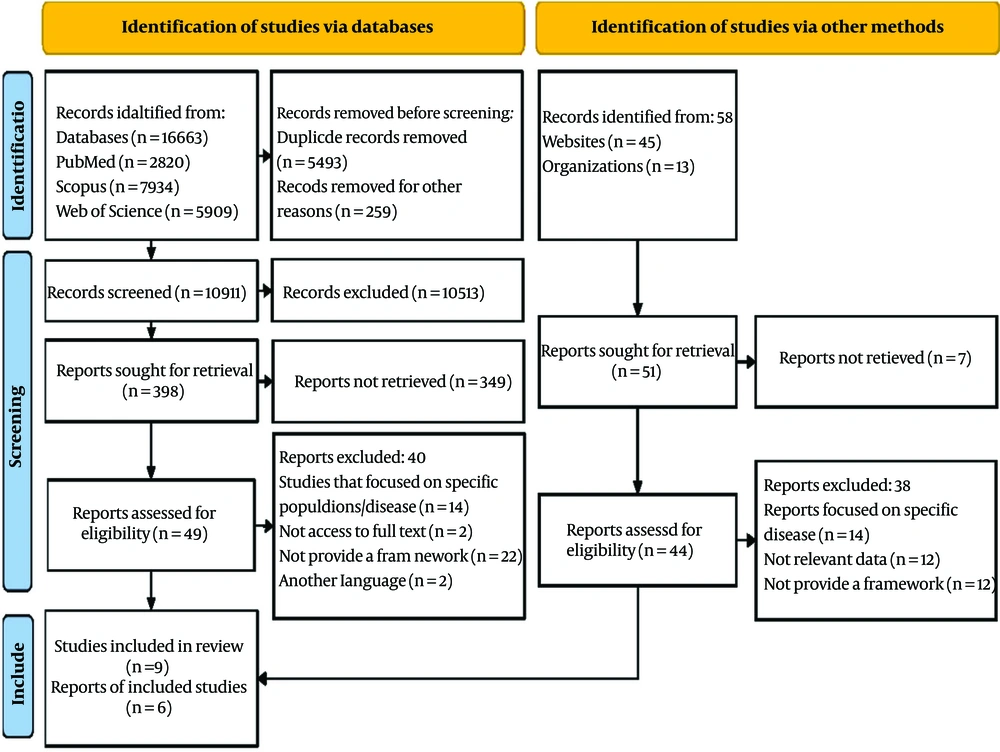

A state-of-the-art review was conducted in 2022 based on the guidelines of systematic reviews included in the “Systematic Reviews to Support Evidence-based Medicine” book (26) and PRISMA 2020 statement (27, 28). Reports and papers related to PHCQAFs were reviewed systematically to achieve the study goal.

2.1. Search Strategy

Three well-known databases, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of knowledge, were used to identify all primary studies up to January 2022. The following search strategy was used in PubMed (Quality [Title/Abstract] AND “Primary Healthcare”[Title/Abstract] OR PHC[Title/Abstract] OR “Primary Care”[Title/Abstract] OR “Primary health services”[Title/Abstract] OR “Basic Healthcare”[Title/Abstract] Assessment[Title/Abstract] OR Evaluation[Title/Abstract] OR Monitoring[Title/Abstract] OR Measurement[Title/Abstract] OR Improvement[Title/Abstract] OR Indicator[Title/Abstract] OR Index[Title/Abstract] AND pattern[Title/Abstract] OR framework[Title/Abstract] OR model[Title/Abstract]) (Appendix 1 - search strategy in all databases). After searching databases, several websites such as WHO and World Bank were also searched to identify and cover most of the reports. After excluding the irrelevant articles based on the study aims and inclusion criteria, the reference-by-reference check was used to find additional articles and enhance the identification reliability of the paper.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were frameworks focusing on the whole PHC systems, frameworks providing QAIs and QDs, and studies in the English language. The exclusion criteria were studies/reports on specific populations such as the elderly and children, studies/reports on specific diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, and studies assessing a particular service or process quality.

2.3. Study Selection

All identified documents were inserted into Endnote X9 software to select eligible studies, and duplicates were removed. At first, studies were screened based on titles and abstracts. Next, the first author (R. R.) and another reviewer (S. A. A.) screened remained studies using the eligibility criteria. Then, reviewers’ meetings were held to discuss and resolve any discrepancies. A minimum agreement of 75% was determined as a cut-off point for selecting debatable studies. The selection process (i.e., including and excluding studies and reasons for exclusion) was presented in a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (27, 28).

2.4. Data Extraction

Three data extraction forms (comparative tables) were created manually in Word 2010 software based on the experience of researchers and the initial review of the frameworks (Detail information of framework, QDs comparison, and QAIs comparison). Two reviewers (R. R. and S. A. A.) extracted the data independently. Differences in extracted data were resolved by discussion. Extracted information in Form 1 included the author’s name and publication year, organizations or countries that developed the framework, the number of QDs, and the number of QAIs. Form 2 included QDs, organizations or governments that set the framework and the frequency of QDs between organizations or countries. Form 3 contained QAIs categories, the organization or country that developed the framework, and the frequency of QAIs between organizations or governments.

2.5. Data Analysis

Analysis and reporting of QDs were done in comparison tables by presenting the frequency of QDs in organizations or countries. Analysis of QAIs was done through the content analysis method. Content analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting the themes within the text. Coding to QAIs was performed by two of the researchers. The steps of QAIs analysis and coding were as follows: Familiarity with the QAIs’ titles and definition, assigning a code to each of the QAIs, categories identification (grouping primarily extracted codes in related categories), reviewing and completing identified categories, naming and defining categories (Based on the content of the principles, a name was chosen for each category of similar codes). The QAIs that were matched or identical in the two frameworks were reported in comparison tables.

3. Results

Out of the 16,663 articles found in the mentioned databases and 58 other resources, 5,493 were deleted due to duplication. Then, 10,513 articles were deleted after reviewing the title and abstracts of the articles. After full-text reading, nine articles and six reports remained (Figure 1).

Finally, 14 PHCQAFs were retrieved from Australia, the United States, Canada, Iran, Japan, Austria (national level), WHO, the European Union (EU), and OECD (international level). They contained 94 QDs and 785 QAIs (Table 1.)

| Organization or Country | World Health Organization Region | Number of Indicators | Number of Dimensions | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Health Organization (29) | - | 34 | 6 | 2016 |

| Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (30) | - | 26 | 3 | 2004 |

| Australia (31) | Western Pacific Region | 139 | 15 | 2005 |

| Australia (22) | 36 | 7 | 2012 | |

| European Union (18) | - | 99 | 10 | 2010 |

| European Union (32, 33) | - | 62 | 5 | 2005 |

| Canada (34) | Region of the Americas | 30 | 13 | 2012 |

| Canada (35) | Region of the Americas | 105 | 7 | 2005 |

| Iran (17) | Eastern Mediterranean Region | 40 | 7 | 2019 |

| Austria (36) | European Region | 30 | 5 | 2017 |

| Japan (37) | Western Pacific Region | 42 | 5 | 2018 |

| USA (38) | Region of the Americas | 54 | - | 2008 |

| USA (39) | Region of the Americas | 58 | 8 | 2013 |

| USA (40) | Region of the Americas | 30 | 3 | 2022 |

| Total | 785 | 94 |

Australia (2005) and Canada (2012), with 15 and 13 dimensions, have defined the highest number of QDs. Accessibility, coordination, safety, effectiveness, and efficiency were the most frequent QDs. The least frequent QDs, with a relative frequency of 7.7%, were preventive care, diagnosis, and treatment, health status, equity, communication, information, finance, responsiveness, clinician-patient partnership, technical quality, understanding patient context, management of health information, practice systems, specific health problems, patient health records, collaborating with patients, education and training, facilities and access, equipment for comprehensive care and clinical support processes that existed only in one PHCQAFs. The QDs comparisons are presented in Table 2.

| Dimensions | USA (39) | USA (40) | WHO-EMRO (29) | European Union (18) | European Union (32, 33) | Australia (31) | Australia (22) | Canada (34) | Canada (35) | OECD (30) | Iran (1) | Austria (36) | Japan (37) | Total a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Health promotion | * | * | 2 (15.4) b | |||||||||||

| 2. Preventive care | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 3. Diagnosis and treatment | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 4. Governance | * | * | * | 3 (23.1) | ||||||||||

| 5. Economic conditions | * | * | 2 (15.4) | |||||||||||

| 6. Staff development | * | * | * | 3 (23.1) | ||||||||||

| 7. Accessibility | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 11 (84.6) | ||

| 8. Continuity | * | * | * | * | 4 (30.8) | |||||||||

| 9. Coordination | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 (61.5) | |||||

| 10. Comprehensiveness | * | * | * | * | 4 (30.8) | |||||||||

| 11. Efficiency | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (38.5) | ||||||||

| 12. Patient centeredness | * | * | * | * | 4 (30.8) | |||||||||

| 13. Effectiveness | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (38.5) | ||||||||

| 14. Safety | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (46.2) | |||||||

| 15. Timeliness | * | * | 2 (15.4) | |||||||||||

| 16. Health status | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 17. Health system infrastructure | * | * | * | 3 (23.1) | ||||||||||

| 18. Management of health information | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 19. Acceptability | * | * | * | 3 (23.1) | ||||||||||

| 20. Equity | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 21. Appropriateness | * | * | * | 3 (23.1) | ||||||||||

| 22. Quality | * | * | 2 (15.4) | |||||||||||

| 23. Communication | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 24. Information | * | * | 2 (15.4) | |||||||||||

| 25. Finance | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 26. Quality and safety | * | * | * | 3 (23.1) | ||||||||||

| 27. Responsiveness | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 28. Clinician-patient partnership | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 29. Technical quality | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 30. Practice systems | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 31. Understanding patient context | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 32. Specific health problems | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 33. Patient health records | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 34. Collaborating with patients | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 35. Education and training | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 36. Facilities and access | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 37. Equipment for comprehensive care | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| 38. Clinical support processes | * | 1 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| Total | 8 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | Sum = 94 |

Abbreviations: OECD, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Frequency is 2 (considered by two frameworks), so the relative frequency (percent) becomes: (2/13) × 100 = 15.4 %.

The PHCQAF from Australia, 2005, has the highest number of QAIs (n = 135). The QAIs related to smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, diabetes care, vaccination, chronic heart disease care, respiratory/infectious disease care, hypertension care, population coverage, community participation, customer satisfaction, maternal and child health, adverse event, health information management, staff empowerment, referral system, and patient rights were the most frequent among PHCQAFs. The QAIs related to accreditation andTelephone consulting were the less frequent QAIs as they were included only in two PHCQAFs (Appendix 2). Comparisons of QAIs are presented in Table 3.

| Indicator’s Category | USA (38-40) | WHO-EMRO (29) | European Union (18, 32, 33) | Australia (22, 31) | Canada (34, 35) | OECD (30) | Iran (17) | Austria (36) | Japan (37) | Total a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nutrition and obesity | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (55.56) b | ||||

| 2. Physical activity | * | * | * | 3 (33.33) | ||||||

| 3. Smoking, alcohol, and substance abuse | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 (77.78) | ||

| 4. Diabetes | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 (100) |

| 5. HIV/AIDS | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 6. Safe condition | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 7. Vaccination | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 (88.89) | |

| 8. Chronic heart disease | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 (100) |

| 9. Respiratory/infectious disease | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (66.67) | |||

| 10. Hypertension | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 (100) |

| 11. Population coverage | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (66.67) | |||

| 12. Community participation | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (66.67) | |||

| 13. Screening health risks | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 14. Customer satisfaction (provider-client) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 (88.89) | |

| 15. Maternal and child health | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (66.67) | |||

| 16. Cancer screening | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (55.56) | ||||

| 17. Mental health | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (55.56) | ||||

| 18. Adverse event | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (66.67) | |||

| 19. Quality improvement program | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 20. Health information management | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 (77.78) | ||

| 21. Staff empowerment | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 (66.67) | |||

| 22. Referral system | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 (88.89) | |

| 23. Patient rights | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 (77.78) | ||

| 24. Team working | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 25. Appropriate prescribing | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (55.56) | ||||

| 26. Lipid disorders | * | * | * | 3 (33.33) | ||||||

| 27. Accreditation program | * | * | 2 (22.22) | |||||||

| 28. Financing and health expenditure | * | * | * | 3 (33.33) | ||||||

| 29. Teleconsultation | * | * | 2 (22.22) | |||||||

| 30. Home care | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 31. Out-of-hours care | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 32. Medication and equipment sufficiency | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 33. Pregnancy care | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 34. Medication safety | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| 35. Emergency/ambulatory care | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (55.56) | ||||

| 36. Waiting time | * | * | * | * | * | 5 (55.56) | ||||

| 37. Self-care | * | * | * | * | 4 (44.44) | |||||

| Total | 26 | 17 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 12 | 23 | 16 | 17 | Sum = 195 |

Abbreviations: OECD, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Frequency is 5 (considered by five frameworks). So, the relative frequency (percent) becomes: (5/9) × 100 = 55.56%.

4. Discussion

According to the results, 14 PHCQAFs with 94 QDs and 785 QAIs were retrieved. Accessibility, safety, coordination, effectiveness, and efficiency were the five most frequent QDs. Moreover, QAIs related to smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, diabetes care, vaccination, chronic heart disease care, respiratory/infectious disease care, hypertension care, population coverage, community participation, customer satisfaction (provider/client), maternal and child health, adverse event, health information management, staff empowerment, referral system, and patient rights were the most frequent and they were shared in more than half of the PHCQAFs. The frequency of QDs and QAIs between PHCQAFs shows their importance. However, differences in QDs and QIs illustrate different countries’ health system contexts.

The QDs are named based on the QAIs’ features and experts’ opinions (17). The results of this study showed that the same QAIs in different PHCQAFs were classified into different QDs (31-33, 37). In addition, similar QDs in different PHCQAFs were introduced with different names (32, 37). In Table 2, comparing QDs, attempts were made to write the exact title of the QDs, and the integration of similar QDs was avoided. As mentioned in that table, many QDs can be integrated. For example, patient centeredness can be integrated with understanding patient context, and management of health information can be integrated with information and patient health records (32, 37). It is suggested that responsible international organizations, such as WHO, develop a set of dimensions as a reference for developing PHCQAFs and that countries use it as a basic framework.

In the QAIs comparison table (Table 3), only those indicators repeated by at least two PHCQAFs were reviewed. As mentioned in this table, many essential services have been missed in the PHCQAFs or mentioned only in one. For instance, indicators such as water hygiene and health workers’ safety are among the indicators that have been neglected. The reason for this could be the differences in the PHC service packages. Moreover, 21 (56.75%) indicator categories were considered in more than 50% of the PHCQAFs. This shows that the frameworks are very similar to each other.

The QAIs categorized in the QD of equity and accessibility have more similarities to different PHCQAFs (21, 31, 39). Accessibility has the highest frequency (84.6%), and equity has the lowest frequency (7.7%); it was suggested to integrate these two QDs. Also, QAIs categorized in the QD of effectiveness, technical quality, and clinical support processes have more similarities to different PHCQAFs (29, 31, 40). As the efficacy has the highest frequency (38.5%), and technical quality and clinical support processes have the lowest frequency (7.7%), it was suggested to integrate these three QDs.

The OECD PHCQAF has used exclusive QDs (health promotion, preventive care, and diagnosis and treatment) for quality indicators based on PHC missions (30). The QAIs in these PHCQAFs are focused on PHC services and outcomes. Performance indicators for PHC principles (such as community participation, intersectoral coordination, etc. (2)) have not been provided in the OECD PHCQAF.

Furthermore, the components of PHC presented in the Alma-Ata statement (1) show that some features, such as access to essential drugs, occupational health, and oral and dental health, were ignored in PHCQAFs. However, the PHC components, such as vaccination, mental illness, and maternal and child health, were presented in most PHCQAFs as QAIs. Achieving health system reform goals, including improving health, patient experience, and affordable costs, depends on establishing and strengthening a comprehensive PHC system (41). Therefore, it is essential to consider the components and principles of PHC regarding disease transition and innovation in developing comprehensive PHCQAFs (41, 42).

Today, non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, respiratory diseases, diabetes, and mental illness, are among the most important causes of death (43, 44). Cardiovascular diseases are the primary cause of death and account for 30% of deaths globally, especially in LMICs (45-47). Studies have argued that controlling, managing, and preventing chronic illnesses differ from acute ones and require a quality PHC system (42, 43). In this regard, QAIs related to cardiovascular and respiratory care services, diabetes, and mental illness were used in most of the studied PHCQAFs. This should also be considered in LMICs with a growing incidence of chronic diseases (42, 46), and it must be regarded as a priority in their PHC. In addition, it was revealed that PHCQAFs had paid little attention to HIV/AIDS. About the growing spread of HIV/AIDS as a chronic disease (42), assessing the quality of HIV/AIDS prevention and management processes in PHC should be one of the main issues for international and national PHCQAFs, especially in LMICs (17).

There are consistent and contradictory experiences regarding the existence of standards and comprehensive frameworks to assess the quality of PHC to compare health system performance at the international level (17, 32, 48). Some believe that each country’s framework should be based on demographic indicators, health status, health system structure, and type of service delivery systems (48, 49). While acknowledging these issues, others believe that most health systems have similar goals and face challenges such as demographic change, limited resources, and rising costs. Hence, using the same frameworks to compare health system performance can provide opportunities to learn from the experiences of other countries (17). The results of this study can provide a practical tool and evidence for developing a comprehensive and valuable framework that includes similarities and differences between different health systems.

This study reviewed the PHCQAFs provided for the whole PHC system. The most critical limitation can be the lack of reviewing QAIs provided outside the PHCQAFs or for part of the PHC system. Since this study aimed to investigate the differences and similarities of PHCQAFs, these studies and reports were not included.

5. Conclusions

There have been many PHCQAFs across different countries and international organizations during the last few years. A comparative framework was developed using a scientific methodology to compare various QAIs and QDs. There were similarities and differences among PHCQAFs. However, international PHCQAFs showed to be more coherent and comprehensive than national ones. Differences in PHCQAFs increase the cost of data collection and conflict of interest. It is suggested to develop complete and reliable PHCQAFs. The findings provide a ready way for health policymakers to address key quality aspects that can help countries accelerate progress in the quality of PHC. Among LMICs, Iran was the only country that provided PHCQAFs. High-income countries provided other PHCQAFs. Low and middle-income countries can use the evidence presented in this study, especially the experiences of Iran, to develop a framework for assessing the quality of PHC appropriate to the context of their health system.