1. Background

The public health sector in various developing and emerging economies is undergoing unfavorable conditions and suffering from insufficiencies in both financial and human resources (1). Available resources are limited while public demand is on the rise. Emerging challenges, including pandemics such as COVID-19 and epidemics of infectious or non-infectious diseases, have exacerbated the situation and caused a tremendous burden on public healthcare systems worldwide. Accordingly, several countries are faced with inconsistencies between planned objectives for reaching desired health measures and budgets allocated to service provision and workforce development. Along with this threat, the private sector in developing economies has also developed simultaneously, now playing a significant role in providing services (2).

One of the main strategies for tackling insufficiencies in resources is to form a public-private partnership (PPP) to utilize the capacities of both sectors in reaching planned health objectives. Public-private partnerships are essentially cooperation between governmental and private organizations for utilizing shared financial, human, technical, and informational resources to obtain the planned objectives agreed upon by the organizations. It should, however, be noted that such partnerships have been adopted in various high, low, and middle-income economies. Yet, the economic crisis encountered by many countries in the 1980s necessitated such cooperation, entailing the preface to various PPPs in the health sector (3).

The proceedings for joining such partnerships between the public and private sectors may vary. For example, such partnerships in the health sector can include rehabilitation, construction, maintenance, management, and provision of minor and major services. Some sectors also exploit the benefits of outsourcing as a form of partnership wherein non-core jobs are delegated to the private sector so that the public sector can effectively keep up with its primary obligations of stewardship, procurement of resources, financial supply, and provision of basic services (4). Since 1993, the World Health Organization (WHO) has acquired the support of Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs) and private sector institutions for improving global health and implementing the health for all initiative. This led to further interactions with the private sector premised on the formation of effective PPPs. As a result, associations with WHO initiatives have become the primary procedures for implementing health for all (5).

As for primary healthcare, a total of 70 global partnerships have been identified. These emerging patterns of interactions towards world health have provided essential foundations for addressing serious problems, particularly in cases requiring research and development on drugs and vaccines for diseases disproportionately targeting vulnerable and poverty-stricken populations. Various partnerships have been made in the field of infectious diseases, a particular case of which includes joint endeavors for polio eradication and lymphatic filariasis elimination (6).

Public-private partnerships are essentially long-term contracts between the private sector and the government to provide public health services. The private sector is launched into accepting significant risks and responsibilities. However, some authors limit partnerships to include only for-profit organizations, while others include contracts with non-profit organizations, as well. The first recorded instances of PPPs date back to the 1970s and 1980s, when increasing public debts along with multiple economic recessions had compelled the governments to seek the help of private investments in developing health infrastructures and improving services (7).

In attaining organizational objectives, recent findings (2019) by the institute for global health services suggest that governments may proceed to sign contracts with the private sector for the provision of services in matters of finance, design, construction, maintenance, clinical services, and delivery, and non-clinical operations (8). It has become clear that the public health system alone cannot resolve all health-related issues. During the past few decades, changes in epidemiology, demographics, and techniques applied for the provision of services, and consequently alterations in service costs, have exposed the health system to a myriad of challenges. Due to these challenges, health systems are experiencing circumstances that demand financial resources that traditional health structures cannot provide optimally. Therefore, to meet these demands, health systems must undergo changes that capacitate them for more efficient use of human, financial, technical, and administrative resources invested in various sectors. One possible solution is the formation of PPPs in the field of health (9). Therefore, we conducted a scoping review study to clarify the role of PPP in increasing equity, access, efficiency, and improving health services to determine how the healthcare situation with PPP is progressing and whether the continuation of this process will have positive and desirable consequences for health. This study examines research between 2000 (the onset of the Millennium Development Goals Program) and 2020 on PPPs in the field of primary healthcare.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to identify the role of PPPs in providing primary health care worldwide.

3. Methods

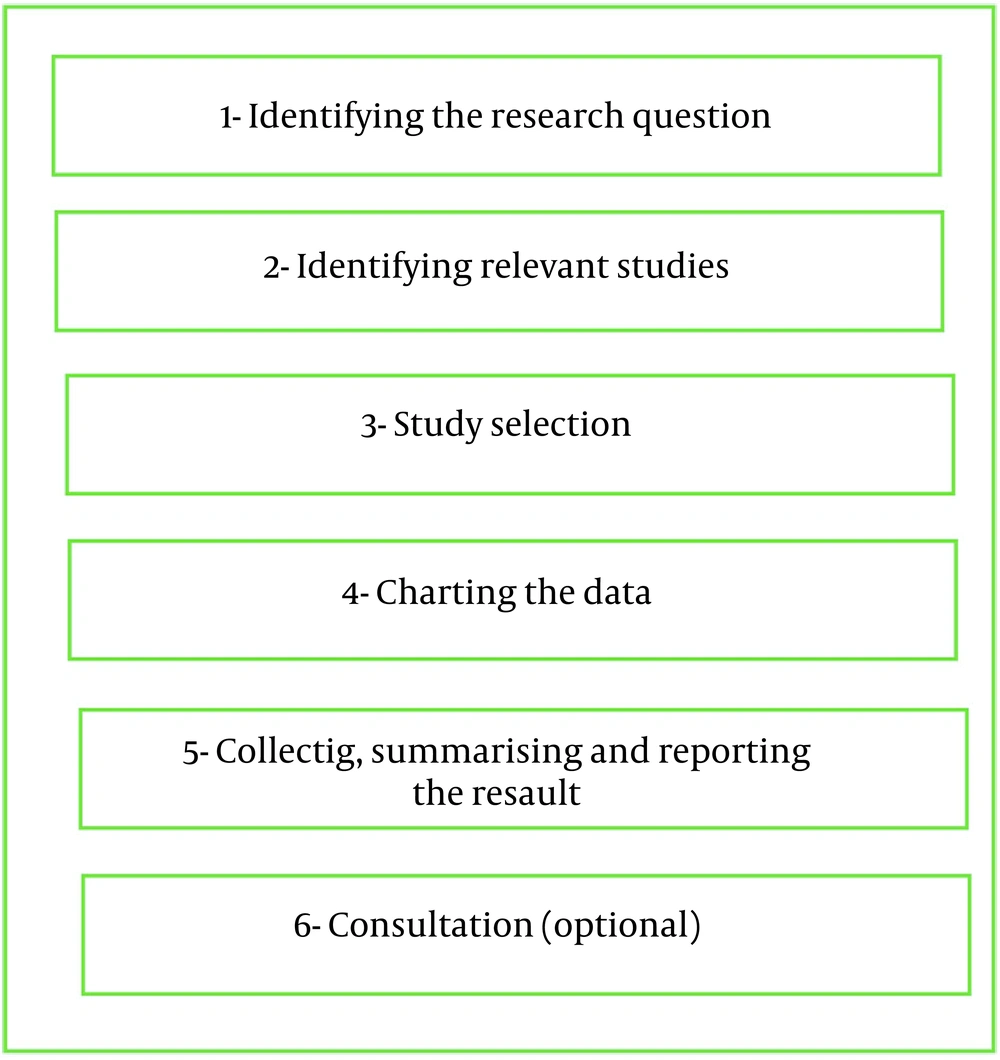

We conducted a scoping review, a type of review often used when a specific research question has not been defined, various methods of data collection and analysis are used, no previous synthesis has been done on the subject matter, or researchers have no intention of evaluating the quality of studies (10). The present study was conducted as a standard scoping review, as shown in the steps below (11) (Figure 1).

3.1. Identifying the Research Question

The research question for this scoping review was investigated based on the PCC (population, context, concept) framework: What are the effects of PPP expansion in the health field on the dimensions of quality of care, such as access, equity, efficiency, and improvement of services? The question was aimed to include all health systems involved in any type of partnership for healthcare services (population) as well as the primary factors affecting PPPs (concept) and structures in which PPPs provide services (context) (12). Relevant studies should be considered to answer the research question.

3.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

The relevant studies forming the study population included studies on PPPs, privatization, and public-private initiatives in the health sectors in different countries. These studies were selected through searches in databases, as shown in Table 1. As evident, relevant studies from 2000 (onset of the millennium development goals) onwards were thoroughly searched through the mentioned databases. The articles were written in English and selected based on the English abstracts indexed in each database.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Search engines and databases: | Pubmed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, Proquest, and Google Scholar |

| Time span- date of search | (2000-2020)- From September to December 2020 |

| Inclusion criteria | Written in English; Published in/after 2000; Categorized as scientific papers; Relevant to public-private participation in healthcare |

| Post-hoc exclusion criteria | Studies conducted before 2000; Lacked full access to article text; Non-English articles; Articles published in non-scientific (non-authentic) journals; Conference abstracts without full text available; No English abstract available; Duplicate articles |

| Search string | #1 AND #2 |

| #1 | "public-private partnership*" or "private-public sector partnership*" or "private public partnership*" or "private-public cooperation" or "private-public sector cooperation" or "public private collaboration" or " public-private collaboration" or " private and public sector collaboration" or "out sourcing" or privatize* or "public-private initiative*" |

| #2 | "health system*" or "health care*" or "health service*" or "health area*" or " Health Sector*" or primary health care |

3.3. Study Selection

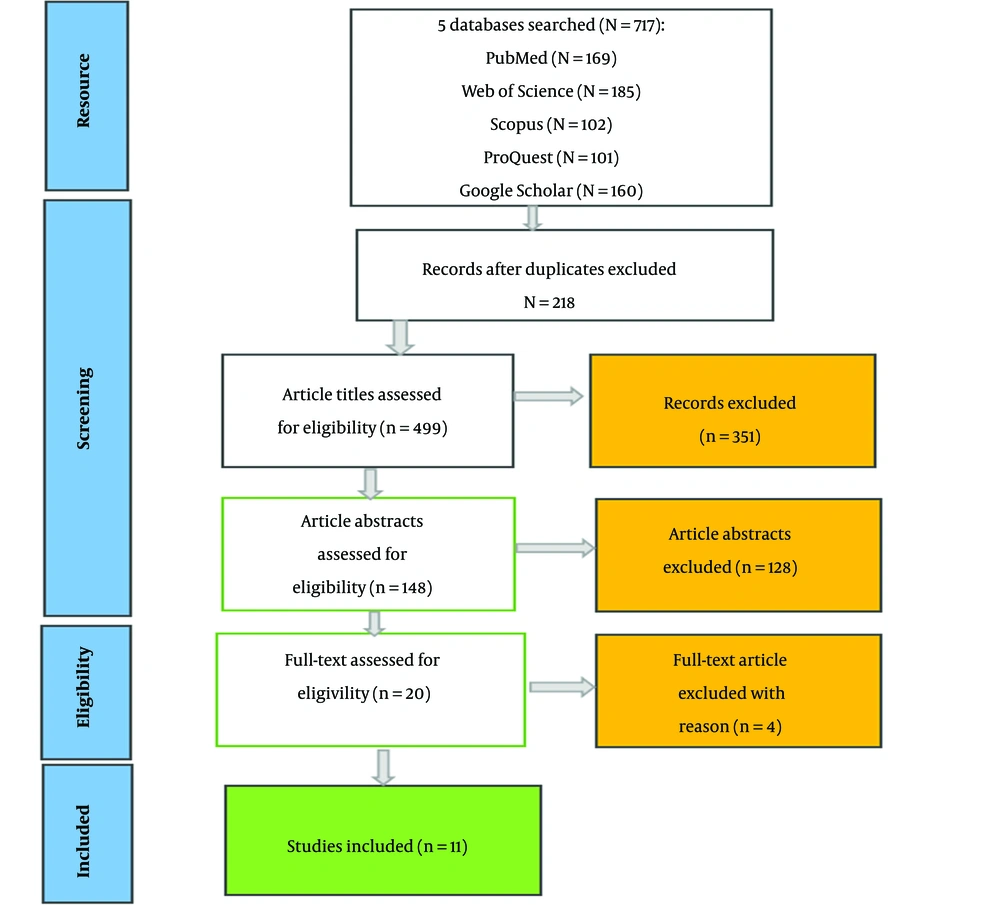

The inclusion criteria for selecting relevant studies are listed in Table 1. The selection procedure was conducted with the initial collection of 717 articles searched using the search strings listed in the table. Repeated articles were removed, and screening procedures were undertaken, leaving 148 articles. These articles were then assessed based on their abstracts and in consistency with the study objectives, leading to 20 studies. After the final reference to the inclusion criteria, four studies were removed due to inconsistencies with the criteria. The remaining 16 articles were kept to investigate according to the purpose of the study (Figure 2). It should be mentioned that the entire study selection process was conducted by two separate researchers, with a final third researcher's opinion for consensus. The selected studies were finally assessed in terms of quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP). The assessment was implemented using the CASP checklists concerning the 10 inclusion criteria, with the condition that a target study must attain at least half the required score (out of 10) to be included in the study. The checklist is as follows: congruence with study objectives, up to date articles, consistency of articles with study design, sampling method used in articles, processes, and quality of data collection methods, reflectiveness and generalizability of results of articles, the accuracy of data analysis processes used, clarity of results, overall contribution and value (13). As a result of this 10-item checklist, 16 articles were included in this study.

3.4. Charting the Data

The included studies were assessed, and relevant data were extracted in forms and stored as Excel spreadsheets. The existing domains were extracted and examined according to Table 2 (14).

| Charting Elements | Associated Questions |

|---|---|

| Publication Details | |

| Author (s) | Who wrote the study/document? |

| Year of publication | What year was the study/document published? |

| Title | What is the title of the article? |

| Origin/country of origin | Where was the study/document conducted and/or published? |

| General Study Details | |

| Aims/purpose | What were the aims of the study/document? |

| Methodological design | What methodological design was used for this study? |

| Strategies emphasized by the study | What strategies are emphasized in this article? |

| Results | What are the results of this research? |

3.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Descriptive analyses of the articles were performed and methodologies and overall strategies used in the articles - to attain the related objectives and contribute to/affecting primary healthcare - were identified and charted. The results are summarized in Table 3, emphasizing available knowledge and findings obtained from the included articles.

4. Results

Of the 16 articles included, 10 (62%) were related to developing economies, two (13%) to developed economies, and four (25%) were conducted globally. Most articles were on infectious diseases, with a total of five articles (29%). Three (18%) articles were about vaccination, and two (12%) studies were on non-infectious diseases. The main emphasis of the articles was directed towards the role of PPP in responsiveness to providers, reducing costs, service coverage, performance, favorable results, and improving referral systems. Moreover, at least one quality measure was assessed or affected in each article out of the indices provided by the WHO, including health equity, security, effectiveness, performance, disease orientation, and timeliness of services (15). The primary research topic in the articles was aimed at improving access to services and promoting their quality (eight articles). The most frequent methodologies among the case studies (four articles) suggested the effectiveness of PPP in providing primary healthcare services and mentioned the challenges posed by such partnerships (Table 3).

| Author (s) | Time | title | Place | Study Aim | Type | Strategies emphasized study | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheikh et al. (16) | 2006 | Public-private partnerships for equity of access to care for tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS: lessons from Pune, India | India | Investigating public-private partnerships (PPP) in the health framework in line with the goal of health justice | Mix method | Increased patient selection for treatment and other services; Increased interaction with the private sector for distribution and sharing of information; Designed partnerships and education plans based on a synergistic framework by the agency of the government and the private sector; Dedication of involved partners to policies of public-private partnership | PPP endorsed healthcare services for AIDS patients and served to meet different individuals' diverse and often conflicting needs by increasing access to healthcare services. Also, it improved the referral system and continuity of patient care. |

| Ardian et al. (17) | 2007 | A public-private partnership for TB control in Timika, Papua Province, Indonesia | Indonesia | Descriptors of successful cooperation between national (governmental) and private health service providers | Quantitative | Observation of national guidelines by service providers; Political commitment and coordination between governmental and private sectors; Accurate identification of different parts of the plan; Identification of the main agents and stakeholders and their mode of communication | An innovative model that can attain sustainable results in controlling, diagnosing, and treating tuberculosis as well as extending access to services, attaining the millennium development goal for tuberculosis (TB) |

| Silk et al. (18) | 2009 | The Central Massachusetts Oral Health Initiative (CMOHI): A successful public-private community health collaboration | USA | Improving access to quality oral health services | Case study | Support for changes in oral health policies; Introduction of new and comprehensive approaches; Regular communication and assessment of involved partners; Coordination of resources among partners; Partnerships with other involved sectors | Sustainable results in terms of access to healthcare services, increasing capacity of health facilities, and training and education for health personnel; Improved quality |

| Pal and Pal (19) | 2009 | Primary health care and public-private partnership: An Indian perspective | India | Assessing the qualifications and increased quality of PPP for primary health care | Systematic review | Better mechanisms of service provision; Mobilization of resources for healthcare services; Targeted services for low-income populations and improved self-regulation and responsiveness; Reduced parallelism of services and selection of the most optimal mode of service | One of the main goals of health system reform is to promote appropriate PPP. PPP in primary healthcare has helped promote responsiveness to user needs and is considered an appropriate measure for advocating public health. |

| Levin and Kaddar (20) | 2011 | Role of the private sector in the provision of immunization services in low- and middle-income countries | Global | Assessing the performance of the private sector based on national economic status and type and capacities of governments | Literature review | Arranged facilities by the private sector in coordination with the governmental sector; Facilitation of new services; Governmental focus on education, coordination, financial supply, and partnerships and contracts with the private sector; Private partnerships for policy-making and planning | In low-income countries, partnerships with the private sector have led to better access to vaccinations, while middle-income countries incorporated partnerships in delivering new vaccines and technology have not yet been fully exploited by the public health systems. Non-profit sectors play a major role in promoting access to routine immunization services. |

| Rao et al. (2) | 2011 | Leveraging the Private Health Sector to Enhance HIV Service Delivery in Lower-income Countries | Ethiopia | Assessing the role of the private sector in promoting national responsiveness to HIV and leveraging the sector’s capacity for different services | Quantitative | Observance of national clinical guidelines and quality standards on the part of the private sector; Interaction between different governmental agents in providing services; Systematic placement of private partners in discussions on policies; Identification of for-profit and non-profit organizations ; Establishing robust monitoring policies and environments, as well as proper incentives | Resources, skills, and expertise of the private sector can increase the use of services, quality, and accessibility. Despite its benefits, partnerships face specific challenges, including unbalanced partnerships and a lack of easy access to financial resources. Such challenges can, however, be alleviated through creative policy-making and new approaches. Given the shortage of philanthropists and domestic public resources, it is essential to exploit the role of the private sector to its fullest potential. |

| Sood and Wagner (21) | 2012 | For-profit sector immunization service provision: does low provision create a barrier to take-up? | Kenya | Assessing the role of the private sector in the provision of immunization services | Quantitative | Increased interaction with the private sector on the part of the government; Technical and financial cooperation with the private sector; Incentives for the participation of the private sector | Only one-third of existing for-profit centers included immunization services. Despite the high contribution of private service providers, vaccination coverage for kids was not relatively high. Also, 29% of private sectors received technical and financial support from the government for vaccination purposes. Furthered interactions between the government and the private sector resulted in better immunization coverage and reduced inequality in service reception. |

| Kamugumya and Olivier (4) | 2016 | Health system’s barriers hindering implementation of public-private partnership at the district level: a case study of partnership for improved reproductive and child health services provision in Tanzania | Tanzania | Introduction of PPP as an efficient tool for assisting governments in the effective provision of services | Case study | Dynamic interaction between governmental and private sectors towards strategic plans; New social contracts endorsing inclusive partnerships at the local scale; Avoidance of parallel services and troublesome competition | The absence of official contracts with the private sector leads to uneven distribution of risk and other moral perils. Implementing policies incorporating PPPs helps increase governmental services' capacity and promotes service coverage, improving health justice, performance, and quality of services. |

| Grépin (22) | 2016 | Private Sector: An Important But Not Dominant Provider of Key Health Services in Low- and Middle-income Countries | Global | Investigating the role of the private sector in the provision of health services and its impacts on the universal health coverage | Qualitative | Suitable placement of private sectors in accordance with the country’s development level; National health policies in accordance with country category (development level); Identification of service patterns for improved health services; Health for all coverage | The private sector was instrumental in maternal and child care and reproductive health services. They acknowledged the role of the private sector and its positive effects on child care and reproductive health care services. No single approach to partnerships can be determined, as partnerships are inherently variable in terms of social and economic factors as well as the development status of the country. |

| Montagu et al. (23) | 2016 | Recent trends in working with the private sector to improve basic healthcare: a review of evidence and interventions | Global | Assessment of intervention models in private healthcare markets | Systematic review | Identification of failure points in social-economic markets; Problem detection and resolution; Aligning motives of service providers with public health goals | Five models of interventions in the private market for healthcare services were investigated. The most common models of the intervention included social marketing of goods, social privileges, contracts, accreditation, and social marketing vouchers. These models can increase access and, most likely, the quality of services, which must be aligned with the existing health system’s framework and development level. |

| Weir (24) | 2017 | A regional collaborative working to improve health care quality, outcomes, and affordability | USA | Bree collaboration identified specific mechanisms of structure and performance and provided incentives for further engagement. | Case study | The government was considered the primary agent of change; Development based on consensus; Prioritization of services for partnership identification and implementation of proven strategies for improving prioritized issues | Health partnerships in Washington State were identified and studied. Governmental authorities and policy makers were found to operate under a central management system which seeks to improve service quality. The main partners included non-profit organizations, which helped improve the overall outcome of the existing health system. |

| Das et al. (25) | 2017 | Does involvement of local NGOs enhance public service delivery? Cautionary evidence from a malaria-prevention program in India | India | Assessing public participation and partnerships with nongovernmental sectors to promote quality and efficiency of services | Intervention | Identification of demographic features and NGOs qualification, and efforts of local executives; The promotional capacity of the governmental (public) sector; Provision of cost-efficient services; Deployment of key interventions | The proposed plan was significantly affected by the site of implementation, demographic features, and NGOs. The efforts made by local executives determined success or failure and the overall efficiency of plans. Overall, improvements were witnessed in service usage, satisfaction, and the final outcome. |

| Amarasinghe et al. (26) | 2018 | Engagement of private providers in immunization in the Western Pacific region | Western Pacific | The role of the private sector in progressing towards national goals and desired outcomes for vaccination | Case study | Compilation of required policies for partnerships in immunization ; Training and education of private institutions for service provision; Consideration of private capacities in the compilation of plans | Despite policies for partnerships with the private sector for vaccination services, nearly half (50%) of private partners were unaware of such regulations. All private sectors in the studied countries were engaged in partnerships for immunization services. The main reason for referral to the private sector included access to new vaccines and equipment rather than the quality of service. Less than 10% of the target group used services provided by the private sector. |

| Hossain et al. (27) | 2018 | Filling the human resource gap through public-private partnership: Can private, community-based skilled birth attendants improve maternal health service utilization and health outcomes in a remote region of Bangladesh? | Bangladesh | Evaluating the private community skilled birth attendant model | Pre-post cross-sectional design | Improved cooperation between the public and private sectors; Education and training of personnel ; Robust supervision and monitoring; Support for public service providers | Key maternal health services improved during the implementation of the program. Significant increases were seen in the birth rate assisted by seasoned nurses, leading to lower side effects during and after pregnancy and at childbirth. PPPs were considered essential to achieving overall objectives for extending public health services. |

| Awale et al. (28) | 2019 | Effective Partnership Mechanisms: A Legacy of the Polio Eradication Initiative in India and Their Potential for Addressing Other Public Health Priorities | India | Discussions on the various recognized techniques and processes for establishing mechanisms of partnerships and cooperation for the eradication of Polio | Review | Coordination between different levels of service provision and among different stakeholders; Identification of opportunities and weaknesses of plans; Prevention of redundant work and increased synergy over resources; Social mobilization and community-based healthcare | The best PPP model for eradicating Polio was identified based on reviews of the relevant literature and frameworks. Partnerships and coordinated actions on multiple levels and among multiple stakeholders were considered essential factors of success. The PPP model can be used as a template for other plans to eradicate or control different diseases, particularly those which can be prevented through vaccination, or other preventable causes of maternal mortality and newborn deaths |

| Ryan et al. (7) | 2020 | Partnership for the implementation of mental health policy in Nigeria: a case study of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Program in Benue State | Nigeria | Informing about the use of PPPs to implement mental health policies | Case study | Investments in available resources and skills; Merging mental health programs with primary health care services; Multi-dimensional partnerships for the incorporation of different resources and actors | PPPs in mental health services helped with the smooth merging of national mental health policies and international guidelines of WHO, which led to improved services. PPPs were categorized as essential for the rapid extension of mental health services. It is through partnerships and shared use of resources and skills that a successful plan for mental health care can be implemented. |

Health equity, amongst other major health system policies, is also considered a quality measure that seeks to provide services for patients based on their specific needs (15). In three studies, improving equity in access to services, reducing inequality in receiving services, and promoting equity in using services have been considered as the results and products of PPP, improving and promoting health equity. Continuity of care is a critical issue in completing the interconnected chain of treatment of patients, especially chronic patients, and one of the ways to continue care is better access to services. In eight studies, improving access to services has been considered one of the positive results of PPP. In particular, PPPs have extended healthcare services for TB and AIDS patients and met the diverse and conflicting needs of different patients while improving the availability of healthcare services (16). Clinical guidelines and standards are required to provide health services. These standards should be developed at the national level, all governmental and nongovernmental sectors should be responsible for its implementation, and the government departments should have the necessary supervision. The development of robust regulatory policies, appropriate incentives, and private sector adherence to national clinical guidelines and quality standards led to better access, improved quality, and reduced costs of caring for AIDS patients (2).

One of the primary instruments of success is planning, and several examples have been implemented by governmental institutes or through partnerships with other sectors concerning primary healthcare. The odds of a plan succeeding depend on an initial road map and a set of clear and precise instructions issued by the government or as the byproduct of interactions and partnerships between involved parties. Regarding the TB control and treatment program, knowing the parties involved in the program's components, explaining the actors' roles, and identifying their relationships helped achieve sustainable TB control achievements and better access to diagnosis and treatment (17). Another example is the Polio Eradication Initiative (PEI), based upon exploiting a system of coordinated service providers of different classes that helped prevent rework through social mobilization and plan-based healthcare (25). The integration of maternal health programs in the health system and the implementation of these programs in partnership with nongovernmental organizations increased the number of skilled attendance and significantly improved the birth rate with the presence of skilled attendance and reported significantly fewer complications during the prenatal, labor, delivery, and postnatal periods. Through PPP, mental health programs were integrated into the WHO National Mental Health Policy and mental health guidelines, resulting in improved service delivery and better public participation in the program. In health programs, an important dimension is the recipient of services. In this study, it was mentioned that for the rapid expansion of mental health services, PPP is necessary, and in this way, problems can be solved, and people's participation in the program can be more obvious. Identifying the characteristics of the population and nongovernmental organizations providing services, quality, and efforts of local implementers and expanding their critical interventions improved the quality and effectiveness of the malaria prevention and control program, so that this program inherited and became a model for other disease prevention programs (28). This study showed that to reform the health system in the field of participation, the government is considered the first factor of change, and the implementation of the development process should be based on consensus, and services for participation should be prioritized. These measures require ongoing communication and evaluation and mutual coordination between program partners. According to the Washington State Health System Participation Survey, the result was improved services, better quality of care outcomes, and better access to care by encouraging more and better interaction with stakeholders (18, 24). There is no single model for participation in the health field, so the design of national health policies and the use of the capacity of other sectors varies according to the country's level of development and social and economic factors. Designing policies appropriate to these conditions made the provision of maternal and child services by the private sector acceptable to the public, and the impact of participation on child health and reproductive health indicators has positive growth (4, 27).

The provision of participatory services in countries also varies according to their level of development. In the field of vaccination services, the nongovernmental sector in low-income countries try to provide services and improve access to vaccines, but middle- and high-income countries try to provide new vaccines and services that are not universal in the public sector and act as facilitators for new services. Also, in the program of vaccination and interaction with the private sector, the countries under study had developed desirable participatory policies, but pertinent information was not provided, so 50% of the private sector was unaware of these policies. Increasing the awareness and transparency of tasks has improved performance and vaccination coverage. Reducing inequality in promoting immunization has been a faithful and conscious participation achievement because people come to the private sector for various reasons, including getting new vaccines, convenience, saving time, and more respect and attention (20, 21). One of the main challenges of PPP was the weak role of private partners in decision-making, and consequently, this sector's motivation was low, so the dynamic relationship between government and private sector in the direction of long-term plans improves participation and plays a role in decision-making. Also, the existence of social contracts to support participation at the local level and prevent the provision of parallel services will improve equity, efficiency, and the quality of services. Moreover, by implementing PPP policies, the service capacity of the government will be helped, and the coverage and benefit of services will be improved, promoting reproductive health and reducing complications of prenatal, labor, delivery, and postnatal periods. Public-private partnerships in the Indian health system are a prime example of a social institution that exploits the advantages of both the government and the private sector. These partnerships have improved the mechanisms behind the provision of health services while increasing resource mobilization, contradicting the claim that PPPs tend to direct resources towards tertiary services. Other advantages of partnerships in primary healthcare services include improved service quality, reduced costs, the direction of public resources towards demand, avoiding rework and repeated services, optimal selection of targeted methods, and providing services for those in need (19).

5. Discussion

The findings of this study revealed clear indications of the effectiveness of PPP as a means for the exchange of knowledge and expertise, as well as the endorsement of public development, resource integration, and efficiency maximization, all in accordance with a specific agenda. Similar joint ventures in the health system are another example of the effectiveness of partnerships that succeeded in extending access to and facilitating health care services, improving overall performance. Reports of case studies in the healthcare sector reveal that a combinatory approach that exploits the advantages of different sectors can lead to better service coverage for target groups, improved responsiveness, higher quality, practical success, lower costs and affordable prices, and consequently, high access to services.

Shrivastava et al. examined PPP's role in achieving UNAIDS/HIV treatment goals in selected countries. Public-private participation in strengthening laboratory systems of disease care was considered a great model and opportunity that can be used to achieve the goals of UNAIDS. This partnership provided many patients with access to services in remote areas and resulted in significant savings in costs and time, as well as the access of many infants to care, and the waiting time to receive the results was reduced by 50%. Despite emphasizing nongovernmental sector participation as an essential partner in disease prevention, participation still requires serious attention to strengthen laboratories. This is consistent with the research results on improving service access, savings costs and time, and improving care indicators (29). Hamzi et al. stated that PPPs had a positive impact on health care delivery, cost savings, and service efficiency; such partnerships satisfied stakeholders with improved access to breast cancer screening, further coverage of dialysis services, and increased access to AIDS policies and programs; they also reduced HIV infection and increased affordability and accessibility to methadone therapy, which is consistent with the results of eight studies concerning improved accessibility (30). In South Africa, NGOs assisted the public health system in fighting AIDS, which simultaneously expressed the inadequacies of the governmental sector in providing quality services for all, particularly those of rural and more deprived or remote regions. Thus, NGOs and other private institutions are essential for public health programs that provide government assistance with technical, financial, informational, and academic support (31). Several factors can help increase the efficiency of partnership plans, including identifying demographic characteristics and key features of a population, such as wealth, religion, and education, as well as the characteristics of executive bodies, service providers, and NGOs, which differ from region to region. Among the studied factors, NGOs obtained overall better results despite their relatively low financial budget by identifying and knowing their target population (25). A study in Russia by Gera and Rubtcova found that Russian citizens often encounter challenges in choosing between the governmental sector of health care (free although slow-performing clinics) and the private sector (fast and easy services), while PPP is considered the third option. Their results indicated the positive impacts of PPP on health care services and the economic progression of health plans, albeit the overall rate of mortality, as a final indicator, remained unchanged (32). From an economic perspective, these findings are concurrent with the present study's findings, although the results contradict each other.

The public-private partnership has been introduced as a global solution to improving health services. Torchia et al. elaborate how PPP, despite being successfully used to address health issues at both national and international levels, is predicated on certain factors to thrive, including the role of involved partners, policy framework, infrastructure, processes, and clear plans (33). The findings in the present study indicate, however, that there is no single approach to forming PPPs, and methods may vary depending on the social, economic, political, and cultural levels of a given society. This idea can be incorporated into national agendas to improve partnerships with the private sector. The first step to ensuring the success of such partnerships is to identify various patterns of services and the socio-economic status of the target population to improve health care services and move towards the primary goal of health for all (22). Concerning vaccination, the findings indicated that services provided in high and middle-income countries differ from those in low-income countries. To elaborate, the for-profit private sector in low-income countries usually provides immunization services and assists in expanding access to vaccines and immunization services. In contrast, in medium-income countries, the private sector has gone beyond common services towards incorporating new vaccines and technologies not yet integrated into the public sectors. Therefore, the type of services provided in each country is subject to its level of income (basic economic country conditions). Nevertheless, low-income countries have also promoted service quality through interactions with the private sector in education, financial support, coordination, and contract work (26).

To a certain point, the TB pandemic was a fine example of the failure of the market, which led to budget deficits and insufficiencies in the provision of facilities for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the disease. The study by Shelby was another example of innovative collaboration endorsed by the Lilly partnership focused on local public health proceedings. The Lilly partnership employed a multi-dimensional PPP approach oriented on obstacles, gaps, and challenges of TB specimens showing resistance to nationally employed drugs through measures to meet basic health requirements. This highlights the significance and positive impact of partnerships in the health field. In fact, the Lilly partnership is considered one of the paragons of cost-efficient agendas that succeeded in upholding national and international public-private initiatives (34). The proposed approach in the program is quite akin to the conceptual framework used in the polio eradication initiative, which is used as a template for plans to control and eradicate infectious diseases.

Political contexts are yet another influential factor when it comes to planned partnerships in the field of health. Thus, in planning the method and type of partnership, one is encouraged to seek political support and leverage, governmental aspirations, and mutual responsibility and accountability. Some of the main human-resource challenges faced in most countries around the world arise out of inappropriate policies and plans, as well as inconsistencies in supply and demand, quality, downsizing, and improper distribution of forces. Successful cooperation of benefactors backed by political and governmental endorsements was implemented in Indonesia, wherein joint efforts were made by all involved parties to plan and distribute human resources towards a Universal Health Coverage (UHC) plan. This collaborative venture succeeded in attaining international support for promoting human resources in the country by mobilizing domestic and international companies' financial and technical resources. The case in Indonesia is yet another example of the effectiveness of PPP in mobilizing human, financial, and informational resources toward planned partnerships aided by governmental support (35).

5.1. Conclusions

Partnerships set into motion various mechanisms for the provision of services and increased mobilization of resources in healthcare that include several advantages, including higher quality, reduced costs, redirecting public resources towards needs, decreased redundancy of services, optimal methods, targeted services for low-income populations, improved self-regulation and responsiveness (19). One of the advantages of PPP in healthcare has been observed in the renovation of governmental medical institutions and improved quality of medical services for the public through the successful implementation of large-scale infrastructural projects. These mechanisms are considered strategic objectives for developing healthcare services, upon which marketing, finance, and organization strategies are added with the overall goal of sustainable development (36).

In the past two decades, various countries have made amendments to their health systems, thereby affecting all related to healthcare services. The new systems require cooperation and interaction among different sectors. India, in particular, has successfully incorporated PPPs in improving basic health indicators, including life expectancy and child mortality. One of the challenges to these proceedings was assuring improvements in quality and fair access to services for the public, which was dealt with by employing new and effective policies for better access to services (37). The significance of PPP is undoubtedly clear in light of the various cases mentioned. However, the distinction is much bolder when the government cannot solely meet the required standards of quality and requires the assistance of other partners to increase service coverage and quality.

Policymakers should consider that one of the primary modes of attaining sustainable development and health for all is PPP in the health sector. Various studies give evidence of the positive impacts of partnerships in the health sector, albeit the overall efficiency of the practiced methods can be improved by gaining knowledge of the local population as well as NGOs and other partners, understanding the rules and regulations, and documents on partnerships, and acquiring political and social support. Without engaging people, health plans are doomed to fail. Through assistance and partnerships, governments can facilitate the processes for achieving health goals and obtaining better results. A proper interaction would be flexible and dynamic, preventing the loss of resources and avoiding parallel and repetitive services, resulting in synergistic progress towards planned goals. As partnerships in planning undoubtedly improve partnerships in the implementation of plans, it is essential that the partners be systematically involved and informed in the process of health policies. Also, PPP can be reinforced by integrating facilities of the private sector with those of the public sector and by aligning the interests and motives of service providers with the goals of public health. Further awareness of plans and information on the capacities of both the public and private sectors is also required, along with a conscious and mutual interaction between the parties, as well as supervisory and monitory mechanisms needed for a synergistic implementation of health plans.

Overall, the impacts of PPP in the health sector have been positive; in most cases, proving successful in attaining the planned goals, the desired quality of service, increased accessibility and responsiveness, and overall cost-efficiency have been proven. These partnerships relieve the government of part of its responsibilities to focus on more primary measures so that it can carry out its core tasks, including stewardship, policy-making, and oversight, with greater focus and power. Because the provision of primary health care in most countries is the government's responsibility, PPP in the cases carried out in this area has had favorable results, but not many studies have been published in this regard, as in the treatment field. It is suggested that more research be done to identify the strengths and weaknesses of PPP in health programs and apply the identified guidelines and techniques to bring PPP to a more favorable state. Regarding the limitations of the present study, we declare that since one of the inclusion criteria was the publication of English articles, those published in other languages were excluded from this study. Moreover, the full text of a limited number of articles was not accessible, which led to exclusion from this study.