1. Background

Burnout is a multidimensional psychological syndrome caused by prolonged exposure to job stressors. It was defined by the three dimensions of emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and reduced personal accomplishment (RPA) (1). Medical staff, especially frontline health workers, suffer from higher levels of burnout in emergencies and public health crises than other staff (2). According to a report, 10% of the confirmed COVID-19 cases were healthcare workers (3). Furthermore, less than 60% of frontline healthcare workers with COVID-19 are reported to have moderate to severe stress. On the other hand, nurses, married individuals, and those with work experience of above 20 days suffered from higher levels of stress (4).

Various studies have documented job burnout in healthcare workers in Iran. A study in 2017 - 2018 revealed the relationship between health sector employees' burnout with RPA and the higher odds ratio (OR) of composite job burnout (CJB) in younger employees (5). Healthcare professionals in a qualitative study also reported EE and RPA during the pandemic (6). Accordingly, intelligent technologies have been recommended to improve their health status, occupational safety, and performance (7). Detecting burnout in health sector employees during the pandemic would help policymakers to consider necessary interventions to prevent and reconstruct different burnout dimensions.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate job burnout and its relevant factors among the employees at the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study encompassed the employees of the SBMU in Tehran, Iran, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the summer of 2020. The inclusion criteria were employing at SBMU and having at least one year of work experience. Individuals with mental disorders or those taking sedatives during the last 4 - 6 weeks were excluded from the study. The sample size was calculated as follows:

Where, p = 0.26 (ratio of employed men at SBMU), d = 0.05, and z = 1.96.

First, 296 men and 1410 women were considered as the sample size; however, 488 men and 1410 women were included in the study, indicating that the male ratio stayed at 0.26.

Data collection tools were a demographic questionnaire and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) with acceptable internal reliability for EE, DP, and PA (8, 9). The EE scores were classified as follows: < 16 low, 16 - 24 moderate, and > 24 high. The DP scores were also classified as follows: < 8 low, 8 - 12 moderate, and > 12 high. Reduced personal accomplishment scores below five were considered low, and the scores 5 - 22 and > 22 were set as moderate, and high, respectively. Regarding the CBJ scores, the scores < 36 were low, the scores 36 - 53 were moderate, and those > 53 were high (10). The univariate and multivariate logistic regression model was used with a binary response variable of job burnout (1 = low, 2 = medium-high).

The convenience sampling method was used in this study, and the participants were those willing to participate in the study. The required data were collected electronically and analyzed using SPSS software version 26 and R4.0.2 software. An electronic questionnaire was sent to all university staff to collect the data. Information for participation in the study was provided via the office automation messaging system to the centers affiliated with the concerned university.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Research and Technology Deputy of the SBMU (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.834).

4. Results

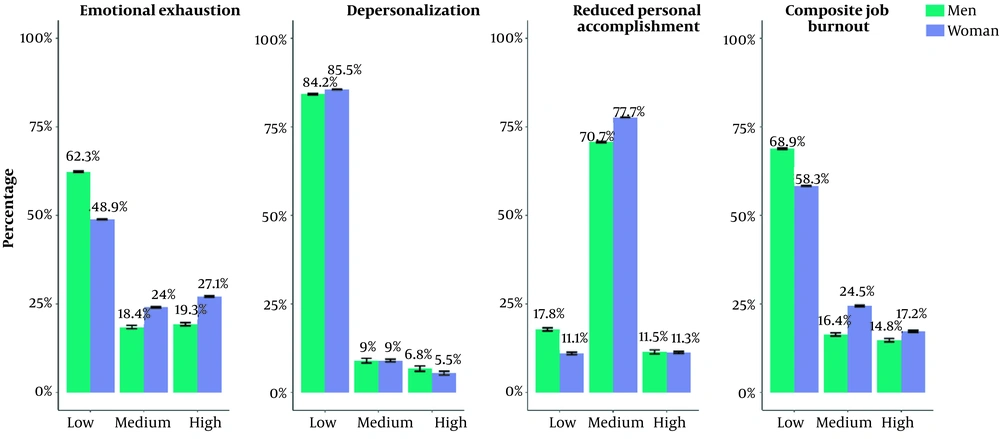

The mean scores of CJB, EE, and RPA were significantly higher in the women group than in the men group (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). The CJB and its dimensions were higher among those aged < 30 years and decreased significantly with aging (P < 0.001). Men and women with < 25 years of work experience showed higher levels of CJB than those with more than 25 years. Women and men working in healthcare centers and hospitals, especially staff exposed to COVID-19, had higher levels of CJB (Table 1).

| Female | Male | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | DP | RPA | CJB (Total Score) | EE | DP | RPA | CJB (Total Score) | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | |

| Age (y) | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | 0.020 a | 0.030 a | 0.005 a | 0.005 a | ||||||||

| < 30 | 19.26 ± 13.09 | 5.33 ± 5.45 | 15.27 ± 8.80 | 39.86 ± 23.85 | 18.00 ± 13.82 | 6.36 ± 5.72 | 13.80 ± 7.01 | 38.16 ± 23.74 | ||||||||

| 30 - 39 | 17.56 ± 11.46 | 4.00 ± 4.62 | 14.17 ± 7.35 | 35.73 ± 19.15 | 14.63 ± 12.21 | 3.76 ± 4.45 | 13.07 ± 7.94 | 31.46 ± 20.21 | ||||||||

| 40 - 49 | 17.19 ± 12.23 | 2.97 ± 3.84 | 12.74 ± 7.02 | 32.90 ± 19.31 | 13.76 ± 13.06 | 3.42 ± 4.99 | 11.39 ± 8.02 | 28.58 ± 22.77 | ||||||||

| ≥ 50 | 14.21 ± 11.13 | 2.32 ± 3.45 | 9.96 ± 6.54 | 26.49 ± 17.21 | 10.43 ± 10.71 | 3.23 ± 5.03 | 9.75 ± 7.42 | 23.41 ± 19.01 | ||||||||

| Work experience (y) | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | 0.012 a | 0.187 | 0.003 a | 0.004 a | ||||||||

| ≤ 10 | 17.14 ± 12.07 | 4.31 ± 4.86 | 14.38 ± 8.07 | 35.82 ± 21.23 | 16.23 ± 12.63 | 4.57 ± 4.87 | 13.35 ± 7.96 | 34.15 ± 20.94 | ||||||||

| 11 - 15 | 17.68 ± 11.22 | 3.77 ± 4.41 | 13.88 ± 6.96 | 35.33 ± 18.54 | 13.43 ± 11.99 | 3.41 ± 4.48 | 12.57 ± 7.40 | 29.41 ± 20.68 | ||||||||

| 16 - 20 | 17.96 ± 12.55 | 3.23 ± 4.32 | 12.95 ± 7.38 | 34.14 ± 19.91 | 14.04 ± 12.79 | 3.58 ± 4.70 | 12.24 ± 9.02 | 29.86 ± 22.55 | ||||||||

| 21 - 25 | 17.84 ± 12.40 | 2.81 ± 3.81 | 11.94 ± 6.73 | 32.59 ± 19.50 | 13.43 ± 13.55 | 3.36 ± 5.38 | 9.93 ± 7.01 | 26.73 ± 22.01 | ||||||||

| > 25 | 13.14 ± 10.97 | 2.20 ± 3.01 | 9.99 ± 6.83 | 25.32 ± 16.80 | 8.96 ± 9.74 | 2.96 ± 5.09 | 9.19 ± 7.40 | 21.12 ± 18.70 | ||||||||

| Exposure to COVID-19 | < 0.001 b | < 0.001 b | < 0.001 b | < 0.001 b | < 0.001 b | < 0.001 b | 0.037 b | < 0.001 b | ||||||||

| Yes | 19.93 ± 11.75 | 4.24 ± 4.70 | 14.47 ± 7.34 | 38.64 ± 20.11 | 17.19 ± 12.94 | 4.60 ± 5.27 | 12.79 ± 8.09 | 34.58 ± 22.41 | ||||||||

| No | 15.01 ± 11.62 | 2.98 ± 4.02 | 12.20 ± 7.35 | 30.19 ± 18.71 | 11.12 ± 11.41 | 2.97 ± 4.36 | 11.28 ± 7.73 | 25.38 ± 19.64 | ||||||||

| Work place | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | < 0.001 a | 0.060 | 0.138 | 0.001 a | ||||||||

| Hospital | 18.98 ± 11.53 | 4.19 ± 4.66 | 14.10 ± 7.55 | 37.29 ± 19.62 | 15.51 ± 12.21 | 4.13 ± 4.95 | 12.33 ± 8.04 | 31.98 ± 20.73 | ||||||||

| Faculties and research | 13.59 ± 11.45 | 2.45 ± 3.58 | 11.61 ± 6.77 | 27.65 ± 17.84 | 11.00 ± 11.18 | 1.97 ± 2.75 | 9.58 ± 8.22 | 22.54 ± 19.47 | ||||||||

| Headquarters | 13.08 ± 11.65 | 2.41 ± 3.75 | 10.95 ± 6.86 | 26.44 ± 18.18 | 10.34 ± 11.38 | 3.25 ± 4.80 | 11.38 ± 7.94 | 24.98 ± 20.93 | ||||||||

| Healthcare centers | 18.73 ± 12.24 | 3.31 ± 4.05 | 14.10 ± 7.41 | 36.15 ± 20.12 | 17.68 ± 14.42 | 3.95 ± 5.16 | 13.13 ± 7.00 | 34.77 ± 23.22 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: EE, emotional exhaustion; DP, depersonalization; RPA, reduced personal accomplishment.

a One-way ANOVA.

b Independent samples t-test.

As presented in Table 2, unadjusted logistic regressions demonstrated that female gender, age groups of 30 - 39, 40 - 49, and ≥ 50 years, bachelor’s, master’s, and higher education, work experience of 21 - 25 and > 25 years, workplace, including faculties, research centers, and headquarters, and exposure to COVID-19 were significantly correlated with the increased likelihood of job burnout. Importantly, female gender, age groups of 40 - 49 and ≥ 50 years, and exposure to COVID-19 were the main independent risk factors for job burnout after adjusting for level of education, work place, and occupation.

| Variables | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-Value | AOR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 1.58 (1.27, 1.97) | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.27, 2.00) | 0.003 |

| Age (y) | ||||

| < 30 | Reference | |||

| 30 - 39 | 0.66 (0.47, 0.93) | 0.016 | 0.64 (0.44, 0.95) | 0.027 |

| 40 - 49 | 0.53 (0.37, 0.75) | < 0.001 | 0.45 (0.28, 0.72) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 50 | 0.28 (0.19, 0.43) | < 0.001 | 0.30 (0.16, 0.55) | < 0.001 |

| Education | ||||

| High school and lower | Reference | |||

| Associate | 1.44 (0.91, 2.27) | 0.121 | ||

| Bachelor | 2.87 (2.03, 4.05) | < 0.001 | ||

| Master and higher | 1.85 (1.27, 2.67) | 0.001 | ||

| Work experience (y) | ||||

| ≤ 10 | Reference | |||

| 11 - 15 | 0.96 (0.75, 1.22) | 0.747 | 1.26 (0.95, 1.67) | 0.104 |

| 16 - 20 | 0.89 (0.67, 1.17) | 0.400 | 1.36 (0.93, 1.97) | 0.106 |

| 21 - 25 | 0.73 (0.54, 0.97) | 0.033 | 1.25 (0.82, 1.90) | 0.289 |

| > 25 | 0.38 (0.26, 0.56) | < 0.001 | 0.88 (0.50, 1.54) | 0.660 |

| Work place | ||||

| Hospital | Reference | |||

| Faculties and research | 0.44 (0.32, 0.62) | < 0.001 | ||

| Headquarters | 0.38 (0.29, 0.48) | < 0.001 | ||

| Healthcare centers | 0.91 (0.68, 1.21) | 0.498 | ||

| Income (million tomans) | ||||

| < 30 | Reference | |||

| 30 - 40 | 1.24 (0.70, 2.21) | 0.460 | 1.24 (0.68, 2.25) | 0.490 |

| ≥ 50 | 1.44 (0.80, 2.56) | 0.222 | 1.64 (0.89, 3.02) | 0.110 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Official and financial | Reference | |||

| Health and medical branches | 2.61 (2.03, 3.36) | < 0.001 | ||

| Service affairs | 0.79 (0.46, 1.37) | 0.414 | ||

| Others | 0.91 (0.60, 1.38) | 0.656 | ||

| COVID-19 exposure | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 2.05 (1.70, 2.48) | < 0.001 | 1.87 (1.54, 2.28) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

5. Discussion

The mean of CJB was moderate among all participants. Compared to men, women showed significantly higher levels of CJB, EE, and RPA; however, the difference for DP was not statistically significant. Differences in ratios might have been caused by different work and life stressors among men and women (11). Furthermore, the mean score of CJB and its components were higher in the age group < 30 years and those with < 25 years of work experience and decreased significantly with aging. Different relationships between age and job burnout might have been caused by differential exposure to constraints and resources. Moreover, some evidence have revealed that job burnout is higher among young individuals during their early years of work, and this is probably because they had not been well-adjusted to their new circumstances (12).

Regarding the participants’ occupation, the largest mean scores of job burnout and its dimensions were observed in the health and medical branches of both genders. Accordingly, healthcare employees are more likely to experience burnout due to the sensitivity of their decisions and long work hours. The present study confirmed that the employees infected with COVID-19 had significantly higher mean scores of job burnout and its components than those not being exposed to COVID-19. Relevant literature has demonstrated that the burnout level among workers was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (13). According to logistic regression results, females and employees with exposure to COVID-19 are significantly more likely to suffer from job burnout than males or those with no exposure to COVID-19. Liu et al. have also reported that the odds of EE was 3.29 times higher among healthcare workers with symptoms of COVID-19 than those without symptoms of COVID-19 (14). Accordingly, gender differences should be considered when providing mental health services to healthcare workers to cope with stressors, especially during the pandemic (15).

The impossibility of having a larger sample size in the present study due to the pandemic was one of the research limitations.

5.1. Conclusions

The results show that although a majority of employees had low levels of EE and DP, they had moderate levels of CBJ and RPA. Effective interventions are suggested to improve individuals’ work-life with an emphasis on critical situations. It is recommended to raise staff’s awareness about the disorder due to its significant relationship with gender, age, and exposure to COVID-19.