1. Background

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in various aspects of good health and a positive lifestyle. Good nutrition is imperative to achieve a better health status (1). Certain iconic tools have been presented by the United States Department of Agriculture to help in making healthy food choices, such as MyPyramid and MyPlate (2). A poor diet might include the overconsumption of sugar, salt, saturated fats, and refined cereals (3). Unhealthy dietary habits and low physical activity levels are closely linked with increased incidence of obesity and its related comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), and some cancers.

The rate of obesity and its related comorbidities is increasing worldwide (4). The portion sizes have also increased and resulted in a spike in overweight and obesity rates (5). Knowledge about nutrition plays a critical role in making healthy food choices. It is one of many factors that tremendously affect the dietary habits and nutritional status of individuals, families, and societies (6). University life is a period when students are independent in making their food choices (7). The chances of adopting unhealthy eating behaviors, such as increased consumption of energy-dense foods, cold drinks, and fast and processed foods, are increased during this tenure (8). Healthy students consume recommended potions of vegetables and fruits daily, an abundant amount of whole grain food items, fish, low salt, and added sugar (9).

Therefore, most well-aware students enjoy better health (10, 11). They remain physically active, and the chances of developing obesity and its related comorbidities become low (12).

The caloric intake and quality of the diet are closely related to food sources (homemade versus restaurant) and the place where the food is consumed (at home versus out of home) (13). Currently, there are numerous information media, many of which are non-credible and promote inaccurate messages about nutrition. University students of various disciplines commonly use potentially inaccurate sources of nutrition information, such as the Internet, media, and family and friends (14). At present, numerous young adults lack nutritional knowledge. They are not informed of the recommended amounts of different food groups (15). They are mostly unable to make healthy food choices. Accordingly, they are more prone to develop different disorders, such as obesity and its related comorbidities (16)

Therefore, unhealthy dietary habits are major risk factors for chronic diseases, particularly if adopted during the early years of adulthood (17). It is vital to explore how much the individuals have nutritional knowledge and follow the dietary guidelines. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the nutritional knowledge of university-going students of various disciplines. The subsequent studies also assessed the nutritional knowledge of university students.

Labban assessed the nutritional knowledge of 998 students from four Syrian universities. The total nutritional knowledge (TNK) was 37.86 ± 0.26 out of ten. Female students had a higher nutritional knowledge score of 38.37 ± 0.35 than male students (37.29 ± 0.38). The TNK of students from private universities was higher than the students of public sector universities (6). Shah et al. also assessed the nutrition-related knowledge of students from the dentistry and nutrition departments. Remarkable inter-group differences (P < 0.05) were noted relative to dietary recommendations regarding the between-mealtime consumption of an extensive range of drinks and snacks. The students from the dentistry and nutrition departments were more worried about their oral health and general health (e.g., obesity), respectively (18). The aforementioned study reported inconsistencies in the diet-related knowledge and attitudes toward dietary advice between the nutrition and dentistry departments.

Ozdogan et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in Ankara, Turkey, to assess the nutritional knowledge of university students (19). A total of 341 students participated, 33.7% (n = 115) and 66.3% (n = 226) of whom were male and female, respectively. The mean score of nutritional knowledge was 15.8 ± 4.9. The mean nutritional knowledge score of female students was higher (16.61 ± 4.34) than male students (14.20 ± 5.50), which was statistically significant (P = 0.00). They reported that all the students had a moderate score in nutritional knowledge.

2. Methods

In this cross-sectional study, the non-probability convenience sampling technique was used to collect the sample. The study sample size was 384 subjects calculated by Cochran’s formula (20):

Nevertheless, only 300 students completed the questionnaire, including 150 students from the Nutrition Department and 150 students from other departments of the University of Lahore, Pakistan. Additionally, 84 students were excluded from the study. The data were collected within January to April 2020. From the Nutrition Department, 108 and 42 students were female and male, respectively. However, from other departments, 77 and 73 students were male and female, respectively.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Undergraduates and post-graduate students (male and female) studying at the University of Lahore were included, and students other than those from the University of Lahore were excluded.

2.2. Questionnaire

The assessment of nutritional knowledge was carried out with the help of a valid nutritional knowledge questionnaire. The questionnaire aimed to give an extensive measure of the nutritional knowledge of students attending the University of Lahore. A pre-tested questionnaire was adapted and was divided into six parts (6, 21). The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were determined by obtaining data through this questionnaire from a small sample consisting of 40 university students. It was ensured that students understood every technical terminology in the questionnaire.

The first part consisted of items about demographic characteristics and anthropometric measurements, such as age, gender, educational level, residential status, height, weight, and body mass index. From the second to sixth part, the correct answer to each item scored 1, and the wrong answer scored 0.

- Part 2: Basic knowledge (8 points)

- Part 3: Dietary recommendations (8 points)

- Part 4: Nutrient sources (13 points)

- Part 5: Food choices/dietary habits (20 points)

- Part 6: Diet-disease relationship (9 points)

The TNK was demonstrated as the sum of the above-mentioned five parts (58 points). The difficulty regarding any item in the questionnaire was resolved on the spot by the researchers. The TNK scores and other parameters were compared based on the participants’ departments and genders.

The height and weight of the participants were measured by flexible steel tape and a weighing machine, respectively. The BMI of the participants was calculated by weight in kilograms divided by height in meter square (kg/m2) and was classified by following the World Health Organization classification.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from this study were quantitative and qualitative and analyzed using SPSS software (version 21). Data analysis consisted of descriptive statistics in terms of frequency, percentages, and mean ± standard deviation. A one-way analysis of variance was used to measure the mean of the two groups. The chi-square test was also used. The mean TNK values of six parts of the questionnaire were calculated. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The confidence level was considered 95%.

3. Results

In the current study, the data about the assessment of nutritional knowledge was obtained from 150 students of the Nutrition Department and 150 students of the non-nutrition departments of the University of Lahore.

The current study showed that most students (n = 180) were under the age range of 22 - 25 years. The ratio of female students was higher (n = 181) than male students (n = 119), as shown in Table 1. The BMI was measured by the aforementioned formula (BMI = kg/m2) by taking the heights and weights of participants. In this study, 101, 97, 54, and 48 participants had BMI ranges of < 18.5 (underweight), 18.5 - 24.9 (normal weight), 25 - 29.9 (overweight), and > 30 kg/m2 (obese), respectively. Most students (n = 282/300) were at the graduate level, and only 18 students were at the post-graduate level. The majority of the participants (n = 174/300) in this study were day scholars, and 126 students were hostelites.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, group (y) | |

| 18 - 21 | 98 (33) |

| 22 - 25 | 180 (60) |

| 26 - 30 | 22 (7.0) |

| Total | 300 (100.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 119 (40) |

| Female | 181 (60) |

| Total | 300 (100.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |

| < 18.5 (underweight) | 101 (34) |

| 18.5 - 24.9 (normal weight) | 97 (32) |

| 25 - 29.9 (overweight) | 54 (18) |

| ≥ 30 (obese) | 48 (16) |

| Total | 300 (100.0) |

| Education level | |

| Graduation | 282 (94.0) |

| Post-graduation | 18 (6.0) |

| Total | 300 (100.0) |

| Residential status | |

| Hostelite | 126 (42.0) |

| Day scholar | 174 (58.0) |

| Total | 300 (100.0) |

3.1. Nutritional Knowledge Score

In part 2 (basic knowledge), the score of female students was higher (4.9 ± 1.32/8) than male students (4.5 ± 1.36/8). In part 3 (dietary recommendations), female (4.0 ± 1.38/8) and male (3.9 ± 1.38/8) students obtained similar scores. Nevertheless, in part 4, the score of female students was slightly higher (7.2 ± 2.15/13) than male students (7.0 ± 2.11/3). However, in part 5 (food choices/dietary habits), the score of male students was higher (8.4 ± 2.01/20) than female students (8.2 ± 2.05/20) with a slight difference.

In part 6 (diet-disease relationship), a higher score was observed for female students (4.1 ± 1.28/9) than male students (3.0 ± 1.14/9). Therefore, the mean TNK of the female students was higher (28.53/58) than male students (27.05/58). Nevertheless, the score of nutrition students was higher (6.1 ± 0.54/8) than non-nutrition students (3.8 ± 1.01/8) for part 2. In part 3, nutrition students also obtained a higher score (4.9 ± 0.41/8) than non-nutrition students (2.5 ± 0.74/8). Nevertheless, in part 4, the score of nutrition students was higher (8.8 ± 1.24/13) than non-nutrition students (6.0 ± 1.27/13). However, in part 5 (food choices/dietary habits), the scores of nutrition (9.8 ± 1.17/20) and non-nutrition (9.2 ± 1.14/20) students were almost similar. In part 6, a higher score was observed for nutrition students (5.2 ± 1.23/9) than non-nutrition-students (2.7 ± 0.85/9). Therefore, the mean TNK of the Nutrition Department students was higher (34.89/58) than students of non-nutrition departments (24.05/58), as shown in Table 2.

| Total Nutritional Knowledge Score | Nutrition Students | Non-nutrition Students | Male Students | Female Students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part 2: Basic knowledge (8 points) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 6.1 ± 0.54 | 3.8 ± 1.01 | 4.5 ± 1.36 | 4.9 ± 1.32 |

| Min | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 8 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Part 3: Dietary recommendations (8 points) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 0.41 | 2.5 ± 0.74 | 3.9 ± 1.38 | 4.0 ± 1.38 |

| Min | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Part 4: Nutrient sources (13 points) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.8 ± 1.24 | 6.0 ± 1.27 | 7.0 ± 2.11 | 7.2 ± 2.15 |

| Min | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 13 | 8 | 10 | 11 |

| Part 5: Food choices/dietary habits (20 points) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.8 ± 1.17 | 9.2 ± 1.14 | 8.4 ± 2.01 | 8.2 ± 2.05 |

| Min | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 15 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

| Part 6: Diet-disease relationship (9 Points) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.2 ± 1.23 | 2.7 ± 0.85 | 3.0 ± 1.14 | 4.1 ± 1.28 |

| Min | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Total: 58 points | 34.89 ± 0.95 | 24.05 ± 1.00 | 27.05± 1.27 | 28.53 ± 1.28 |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||

3.2. Body Mass Index

Female students (n = 61/181) had normal weight as compared to male students (n = 36/119). Similarly, nutrition students (n = 58/150) had normal BMI as compared to non-nutrition students (n = 39/150). However, a statistically significant difference was not observed between gender (P = 0.78) and department (nutrition and non-nutrition students) (P = 0.10) with BMI, as shown in Table 3.

| Variables | Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | Total | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 18.5 (Underweight) | 18.5 - 24.9 (Normal) | 25 - 30 (Overweight) | ≥ 30 (Obese) | |||

| Gender | 0.78 | |||||

| Male | 39 (33) | 36 (31) | 22 (18) | 22 (18) | 119 | |

| Female | 62 (34) | 61 (34) | 32 (18) | 26 (14) | 181 | |

| Department | 0.10 | |||||

| Nutrition | 48 (32) | 58 (38) | 22 (15) | 22 (15) | 150 | |

| Non-nutrition | 53 (36) | 39 (26) | 32 (21) | 26 (17) | 150 | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

3.3. Meal Skipping

Irregularity in meal consumption was observed in this study; accordingly, 33%, 29%, and 31% of male students skipped breakfast, lunch, and dinner, respectively. Only 7% of male students consumed meals regularly. Additionally, 10% of female students used to consume meals regularly. In this study, 43%, 20%, and 27% of female students skipped breakfast, lunch, and dinner, respectively. No statistically significant difference was observed between genders in skipping a meal (P = 0.14). On the other hand, 13% of Nutrition Department students reported regular consumption of meals. However, 45%, 21%, and 19% of Nutrition Department students skipped breakfast, lunch, and dinner, respectively. In this study, 9% of students from non-nutrition departments used to consume meals regularly. Nevertheless, 36%, 23%, and 32% of students from non-nutrition departments skipped breakfast, lunch, and dinner, respectively. Therefore, a statistically significant difference was not observed between nutrition and non-nutrition students (P = 0.11; Table 4).

| Variables | Meal Skipping | Total | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Never | |||

| Gender | 0.14 | |||||

| Male | 39 (33) | 35 (29) | 37 (31) | 8 (7) | 119 | |

| Female | 77 (43) | 37 (20) | 49 (27) | 18 (10) | 181 | |

| Department | 0.11 | |||||

| Nutrition | 68 (45) | 32 (21) | 31 (21) | 19 (13) | 150 | |

| Non-nutrition | 54 (36) | 34 (23) | 48 (32) | 14 (9) | 150 | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

3.4. Use of Dietary Supplements

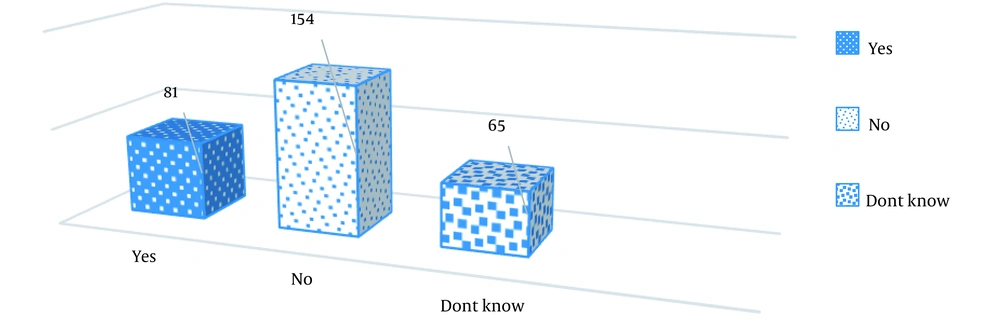

Only 26% and 28% of male and female students reported the consumption of dietary supplements, respectively. However, a statistically significant difference was not observed between genders in dietary supplement usage (P = 0.32). On the other hand, 33% and 21% of nutrition students and non-nutrition students used to consume dietary supplements, respectively. Therefore, a statistically significant difference was noticed between nutrition and non-nutrition students in using dietary supplements (P = 0.00), as shown in Table 5. However, overall, the majority of the students (n = 154/300) did not use dietary supplements, as illustrated in Figure 1.

| Variables | Dietary Supplement Usage | Total | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Do Not Know | |||

| Gender | 0.32 | ||||

| Male | 31 (26) | 57 (48) | 31 (26) | 119 | |

| Female | 50 (28) | 97 (54) | 34 (19) | 181 | |

| Department | 0.00 | ||||

| Nutrition | 49 (33) | 80 (53) | 21 (12) | 150 | |

| Non-nutrition | 32 (21) | 74 (49) | 44 (30) | 150 | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

3.5. Knowledge of Salt and Fat Relation to Diseases

Most female students (44%) were aware that a high intake of salt might cause chronic disorders, and only 37% of male students were familiar with this issue. Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant difference between genders (P = 0.41). Additionally, most female participants (48%) were familiar with the fact that a high intake of salt might cause diseases, and only 37% of male students were familiar with this issue. Therefore, a statistically significant difference was not observed between genders in this issue (P = 0.11).

On the other hand, 61% of nutrition students were aware that a high intake of salt might cause diseases, such as hypertension and CVDs. However, only 20% of non-nutrition students were familiar with this issue. Therefore, there was a statistically significant difference between nutrition and non-nutrition students (P = 0.00). Nevertheless, 63% of nutrition students were familiar with the relationship between high intake of fat and diseases. Nonetheless, only 27% of non-nutrition students were familiar with this issue. As a result, a statistically significant difference was observed between students of nutrition and non-nutrition departments (P = 0.00), as shown in Table 6.

| Variables | Knowledge | Total | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Do Not Know | |||

| Salt Relation to Diseases | |||||

| Gender | 0.41 | ||||

| Male | 44 (37) | 53 (45) | 22 (18) | 119 | |

| Female | 80 (44) | 68 (38) | 33 (18) | 181 | |

| Department | 0.00 | ||||

| Nutrition | 91 (61) | 41 (27) | 18 (12) | 150 | |

| Non-nutrition | 30 (20) | 83 (55) | 37 (25) | 150 | |

| Fat Relation to Diseases | |||||

| Gender | 0.11 | ||||

| Male | 43 (36) | 45 (38) | 31 (26) | 119 | |

| Female | 87 (48) | 59 (33) | 35 (19) | 181 | |

| Department | 0.00 | ||||

| Nutrition | 94 (63) | 36 (24) | 20 (13) | 150 | |

| Non-nutrition | 40 (27) | 70 (46) | 40 (27) | 150 | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4. Discussion

Knowledge of nutrition plays a critical role in making healthy food choices. It tremendously affects the dietary habits and nutritional status of individuals, families, and societies. The present study demonstrated a difference between genders in achieving scores on TNK. Female students achieved higher (28.53 ± 1.28/58) mean TNK than male students, who obtained lower scores (27.05 ± 1.27/58). These results are in line with the results of several studies. Labban reported that female students had a higher nutritional knowledge score (38.37 ± 0.35) than male students (37.29 ± 0.38). Students from health disciplines had higher nutritional knowledge (41.23 ± 0.05) than students of non-health disciplines (36.86 ± 0.28) (6).

Ozdogan et al. also showed a higher mean nutritional knowledge score of female students (16.61 ± 4.34) than male students (14.20 ± 5.50) which were statistically significant (P = 0.00) (19). Some studies (22, 23) also indicated a higher score for female students (mean score = 27.1 and 58.6 ± 12.8) than for male students (mean score = 26.2 and 54.1 ± 13.3) (P < 0.01) (22, 23). In the present study, a statistically significant difference was not observed between genders (P = 0.78) and departments (nutrition and non-nutrition students) (P = 0.10 with BMI. In a similar vein, Mehanna et al. reported no significant association between students’ overall knowledge and their BMI (P = 0.43) (24).

Importantly, this study indicated that nutrition students and female students had higher TNK than non-nutrition and male students, respectively. However, no significant differences were observed in food choices/dietary habits between nutrition and other departments and both genders.

According to the results of the current study, only 7% and 10% of male and female students consumed meals regularly, respectively. In addition, 13% and 9% of the nutrition and non-nutrition departments reported regular consumption of meals, respectively. Zaborowicz et al. demonstrated similar results. In the aforementioned study, 15.9% and 12.8% of female and male students used to consume meals regularly, respectively. Moreover, 32.1% and 38.6% of female and male students skipped meals, respectively. Their statistical analysis showed no significant differences in the nutritional behaviors of the respondents with consideration of gender and nutritional knowledge (25).

In the current study, most female students (48%) were well aware that high intake of fatty foods was closely associated with various negative health outcomes, such as CVDs, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancers. Similar results were also obtained in a study conducted by Mehanna et al. They reported that 97% of female students recognized that high fat intake is related to overweight/obesity and related comorbidities. This study reported that only a few students used dietary supplements (n = 81), and a majority of students did not use dietary supplements (n = 154) with no significant differences in gender (P = 0.32) (24). However, Fattahzadeh-Ardalani et al. obtained contradicting results. They reported that 167 out of 250 students (66.8%) in their study used various dietary supplements, and gender-based usage of dietary supplements was also statistically significant (P = 0.00) (26).

The present study revealed that most of the students (female: 43%; male: 33%) used to skip breakfast regularly. Alkazemi observed similar results. In the aforementioned study, about 35% and 35.1% of female and male students usually skipped breakfast, respectively (27). The current study showed that students recognized that excessive salt intake might result in chronic disorders, such as hypertension, CVDs, and renal diseases. Female participants (44%) were aware that a high intake of salt might cause chronic disorders, and only 37% of male students were familiar with this issue. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between genders (P = 0.41). Cheikh Ismail et al. reported similar findings to a greater extent. Accordingly, most female students were able to accurately describe the association between high intake of salt with hypertension (71.9%), CVDs (66.7%), and renal diseases (69.3%) (28).

4.1. Strengths

The current study showed similar food choices/dietary habits of students from nutrition and non-nutrition departments indicating that Nutrition Department students do not usually apply their knowledge in their food choices. This finding shows that the main problem is not applying nutritional knowledge in daily eating practices among university students. Therefore, this study will be fruitful for policymakers to focus mainly on the translation of nutritional knowledge into daily eating habits/food choices when initiating nutrition education programs. The present study will also be helpful for the researchers who will assess the nutritional knowledge scores of university students.

4.2. Limitations

In the current study, the data were obtained only from the students of the University of Lahore to assess nutritional knowledge. As a result, the findings cannot be generalized to all university students in Pakistan. The sample size is small. It is required to carry out further studies based on a large sample to generalize the results.

4.3. Conclusions

Nutritional knowledge plays a pivotal role in ameliorating dietary choices and maintaining health status. The students at the university level are independent regarding making food choices. If they do not have sufficient knowledge of healthy foods and portion sizes, they cannot improve their eating habits. The assessment of their nutritional knowledge and its application in food choices is essential to launch nutrition education campaigns. Therefore, the current study assessed the nutritional knowledge of university-going students. As a result, the mean TNK of the female students was higher (28.53/58) than male students. Additionally, the mean TNK of the Nutrition Department students was higher (34.89/58) than non-nutrition students. Nevertheless, regarding the food choices/dietary habits part, the scores of nutrition (9.8 ± 1.17/20) and non-nutrition (9.2 ± 1.14/20) students were almost similar. Therefore, students, even from the Nutrition Department, failed to transform their knowledge about nutrition into healthy food choices and eating practices.

A statistically significant difference was not observed between genders (P = 0.78) and departments (nutrition and non-nutrition students) (P = 0.10) with BMI. This finding shows that nutritional knowledge alone is not a predictor of the nutritional status (BMI) of an individual. However, 61% and 63% of nutrition students were familiar with the relationship of high intake of salt and fats with diseases, such as hypertension and CVDs, respectively. Accordingly, they can be better able to change their dietary habits to prevent chronic problems. Consequently, it is necessary to initiate nutrition education programs emphasizing making healthy food choices and recommended portion sizes of various foods. Moreover, nutritional knowledge related to dietary guidelines should be incorporated into daily life to remove the disease burden associated with obesity, especially among young adults.