1. Context

Resource constraints have always been among the challenges that health systems are faced in many countries, especially in developing countries, such as Iran. Therefore, the proper use of available facilities and resources with maximum efficiency is highly essential (1). Given that hospitals are known as the most expensive centers that provide healthcare services in any health system (2), hospital managers have to control these resources for optimal and efficient use (3-5).

Hospital income derives from a variety of sources, including the government budget and direct hospital revenue, part of which is received directly from the patient; however, most of the income is earned through reimbursement from basic health insurance organizations (6). There are three basic insurance organizations in Iran, namely Health Insurance Organization, Social Security Organization, and Armed Forces Insurance (7, 8). According to the law of public health insurance, which covers basic medical services in medical centers, especially in hospitals, most hospital resources are provided by concluding contracts with these organizations.

The main source of hospital income is the services provided to individuals covered by insurance companies. These costs are determined and payable after the audit and exchange of financial and clinical documents of the services provided by hospitals to the insurance organizations and review of these documents by insurance companies. The problem is that during the process of auditing and ensuring hospital records, significant amounts of the costs, entitled as deductions, are not reimbursed to hospitals. In other words, the deduction is the difference between the total amount of hospital expenses and the amount of money reimbursed by insurance organizations (9, 10). This means that hospitals do not receive a portion of the costs for a variety of reasons claimed by insurance organizations. These deductions are not only one of the most important cases of waste of hospital resources (11, 12) but also lead to delays in reimbursement of hospital expenses and increase the financial problems and liquidity of Iranian hospitals in the current economic conditions.

There are various statistics on the amount, fee, and percentage of insurance deductions of Iranian hospitals based on different studies. According to a study in 2020, which examined the deductions of some hospitals in the country, the average cost of deduction applied to a case was announced to be 3,873,723 Rials, which was 5.5% of the total cost of each hospitalized case (13). Furthermore, the reduction of income and financial losses due to deductions in the hospitals affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, was announced up to 180 billion Rials in one year (14). In one study, the total revenue of the hospital was estimated at 316,436,524,031 Rials in one year, of which 57,627,977,004 Rials were not refunded from the total revenue (15). According to the findings of another study, $47,408.62 of hospital expenses ($1 equal to 12,050 Rials in 2012) was not reimbursed due to deductions only by one insurance organization (social security insurance) (16).

In other countries, the issue of deductions as false reimbursement of medical expenses is also crucial. For example, in the United States, peer review organizations are employed by the Health Care Financing Administration to maintain the integrity and solvency of Medicare Advantage plans. The audits of the Medicare Advantage plan in 1998 indicated that more than $12 billion dollars were spent on inappropriate payments to hospitals, with over 25% attributed to the prospective payment system (17).

There are various reasons for the issues of deductions and declined hospital revenues from insurance companies. Numerous studies have been conducted in Iran in this regard (6, 12, 18-20), and different reasons have been mentioned in different studies, along with some solutions to reduce them in a decentralized manner. Since Iran is a developing and low-income country, it is currently in an unstable economic condition. This issue has caused serious problems in the financial resources of the health system, especially for hospitals (21, 22). On the other hand, insurance organizations are the most important purchasers of services provided by health and treatment centers. Due to the ever-increasing price of services provided to patients and budget limitations, stricter rules are applied for the purchase of services day by day (23, 24). In such a situation, health managers and policymakers, both at macro and micro levels of decision-making, should be aware of the root causes of insurance income reduction and solutions and strategies to achieve maximum health insurance income in hospitals. Due to the multiplicity of field studies and lack of coherent studies in this field and considering the importance of this issue in Iran’s insurance context, it is necessary to conduct a review study that can collect and summarize the findings of existing studies and the results can be used as a guide to reduce hospital deductions. This study intends to evaluate and extract the causes of insurance deductions and the strategies to reduce them in Iranian hospitals based on field studies and in a centralized manner. Accordingly, it is possible to provide comprehensive, coherent, and structured data for policymakers and managers of the health system.

2. Methods

This was a scoping review of the literature on health insurance deductions in hospitals in Iran within 2000 to February 12, 2023, to synthesize the findings of original Persian and English studies that focused on the causes of deductions and propose strategies to reduce them in Iranian hospitals. Arksey and O’Malley’s protocols were used to conduct this scoping review, including six steps: (1) identifying research questions; (2) identifying related studies using valid databases, reviewing gray literature, dissertations, review articles, and the references of studies based on the scope of research; (3) selecting related studies for review from the initial studies; (4) extracting the data in the form of graphs and tables; (5) collecting, summarizing, and reporting the findings; and (6) optional consultation with experts about the obtained findings (25). The research questions of the present study were as follows:

What are the reasons or causes of insurance deductions in Iranian hospitals?

What are the strategies to reduce the insurance deductions of Iranian hospitals?

Therefore, this study can provide evidence for policymakers or health managers by outlining the subject matter, key concepts, thematic review of the literature in this field, and the nature and scope of research and identifying ways to reduce deductions (26).

This study used several databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest. The Persian databases, including scientific information database (SID) and Magiran, were also used. Finally, the Google Scholar search engine was used to ensure that all articles were reviewed.

The keywords used in this study were as follows:

- Insurance deductions

- Bill deductions

- Insurance deduction fraud

- Bill deduction fraud

- Health insurance fraud

- Medical claim fraud

- Deductions of insurance bills

- Revenue deficits

- Deductibles and Coinsurance

- Coinsurance and Deductibles

- Coinsurance

- Deductibles

- Cost sharing insurance

- Falsification of receipts

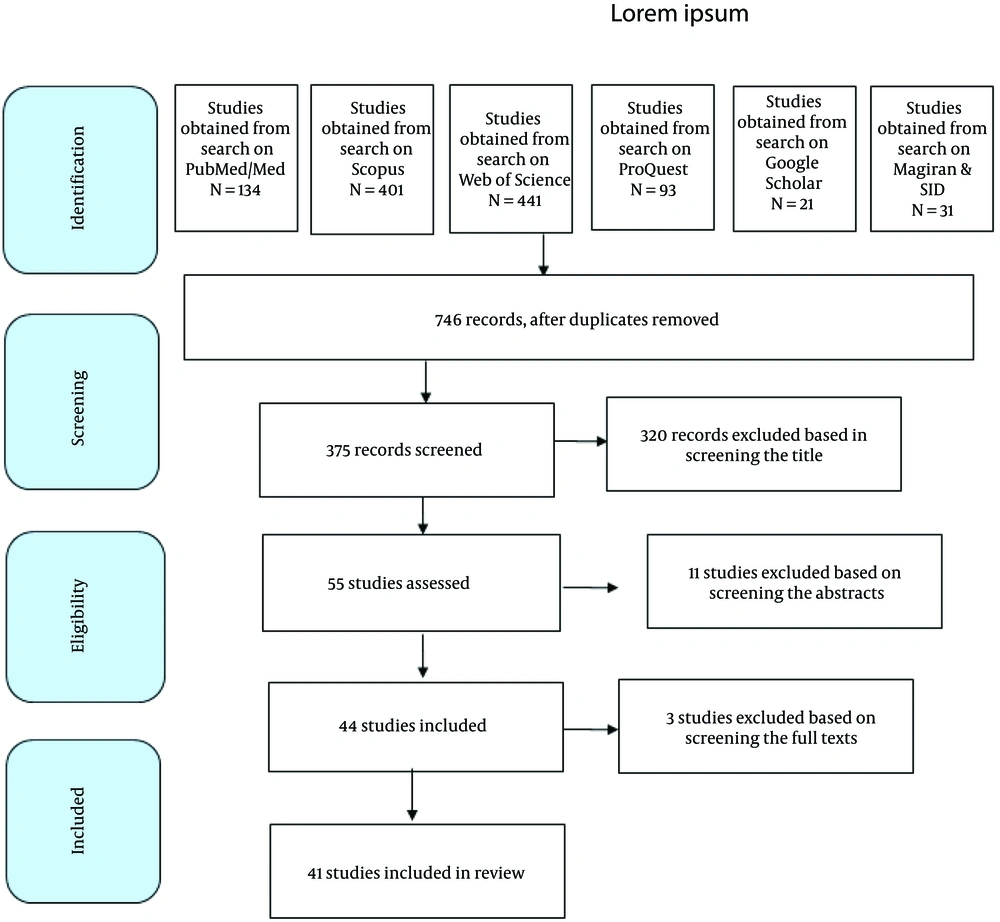

In Figure 1, the flow diagram shows the process of identifying, reviewing, and selecting articles (Figure 1). A total of 1121 articles were retrieved. First, the titles of the articles were evaluated and screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 375 articles were found at this stage. The retrieved articles in English included 21, 134, 401, 441, and 93 articles in the Google Scholar search engine, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest, respectively. In Persian databases, 24 and 7 articles were retrieved from Magiran and SID, respectively. Moreover, 320 unrelated articles were excluded after reviewing the titles of the articles, and 11 articles were omitted after reviewing the abstracts. Out of the remaining 44 articles, 3 articles were omitted after reviewing their full texts because they did not propose any solution to reduce deductions. Finally, 41 articles met the included criteria and were analyzed for final review.

The inclusion criteria in the present study were English and Persian articles published within 2000 to February 12, 2023, which pointed out the causes of deductions and presented ways to reduce them. The exclusion criteria were studies published in languages other than Persian and English and published after February 12, 2023. The articles were screened based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist. The analysis of research data (text of the articles) was carried out using the content analysis technique in MAXQDA software (version 10).

The databases were searched by one of the researchers (R. M.). The articles were independently screened by two researchers (H. R. and R. M.) based on the PRISMA-ScR (27) checklist, and the results were compared and discussed in the presence of a third (E. M.) and a fourth (M. M.) researcher to reach a consensus. To extract the necessary data, a data extraction form was used, including authors’ details, year of article publication, study objectives, year of study, type of research, data collection method, reasons for deductions, and strategies to reduce deductions. The analysis of the research data was carried out by the fifth (E. J. P.) and sixth (A. A.) researchers.

3. Results and Discussion

Figure 1 shows the screening process, distribution of the retrieved articles, and search results based on the PRISMA protocol.

Regarding the study level, 6 articles were conducted at the national level, 15 articles were conducted in hospitals affiliated with a university of medical sciences, and 20 articles were conducted in only one hospital (Table 1).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of study | |

| Review | 2 (4.9) |

| Descriptive | 23 (56.1) |

| Analytical | 8 (19.5) |

| Qualitative | 5 (12.2) |

| Mix methods | 3 (7.3) |

| Study level | |

| Hospital | 20 (48.8) |

| University | 15 (36.6) |

| National | 6 (14.6) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2000 - 2005 | - (0) |

| 2006 - 2010 | 2 (4.9) |

| 2011 - 2015 | 11 (26.8) |

| 2016 - 2020 | 25 (61) |

| 2021 - 2022 | 3 (7.3) |

In the target period of this study, within 2000 to February 12, 2023, the first and last articles were published in 2010 and 2022, respectively. The highest density of published articles was in 2018 and 2019 (eight articles in each year), in 2020 (seven articles), and within 2015 - 2017 (four articles). Tables 1 and 2 show the descriptive characteristics of the selected articles.

| First Author | Research Method | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Level | Study Design | ||

| Maleki | University | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (20) |

| Madahian | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (28) |

| Hosseini-Shokouh | Hospital | A cross-sectional study | (29) |

| Emamgholipour | University | An analytic-applied study | (30) |

| Ghaed Chukamei | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (15) |

| Mousazadeh | Hospital | A cross-sectional study | (31) |

| Norooz Sarvestani | Hospital | A cross-sectional study | (32) |

| Mohamadi | National | A descriptive-analytic study | (13) |

| Rezvanjou | Hospital | A cross-sectional study | (33) |

| Najibi | University | A qualitative study | (24) |

| Mohammadi | University | A descriptive-analytic study | (34) |

| Tabrizi | University | A qualitative study | (35) |

| Safdari | University | A descriptive-analytic study | (36) |

| Alidoost | University | A qualitative study | (37) |

| Bagheri | Hospital | A descriptive-analytic study | (38) |

| Zarei | University | A cross-sectional study | (39) |

| Aryankhesal | National | A systematic review | (40) |

| Askari | University | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (41) |

| Mosadeghrad | Hospital | A descriptive study | (42) |

| Khorrami | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (43) |

| Karimi | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (44) |

| Taheri | Hospital | An interventional cross-sectional study | (19) |

| Imani | University | A mix-method study | (12) |

| Zarei | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (18) |

| Mazdaki | National | A quasi-experimental study | (45) |

| Rostami | Hospital | A descriptive-analytic study | (46) |

| Safdari | University | A descriptive study | (47) |

| Afshari | Hospital | A participatory action research | (48) |

| Safdari | University | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (49) |

| Ferdosi | National | A qualitative study | (50) |

| Karami | University | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (51) |

| Khalesi | Hospital | A longitudinal study | (52) |

| Sarabi-Asiabar | National | A mix-method study | (11) |

| Tavakoli | Hospital | An experimental study (pre-post study) | (9) |

| Khanlari | Hospital | A descriptive-practical study | (16) |

| Sohrabi Anbouhi | University | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (53) |

| Vali Pour | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (54) |

| Mousarrezaei | National | A systematic review | (55) |

| Kharazmi | Hospital | An interventional study | (56) |

| Makhsosi | Hospital | A descriptive cross-sectional study | (57) |

| Hayati | University | A retrospective cross-sectional study | (58) |

Most of the studies were descriptive (n = 23), analytic (n = 8), qualitative (n = 5), hybrid (n = 3), and review (n = 2). Data collection tools in most studies were checklists and data collection forms. Table 1 shows the distribution of studies.

In this study, 46 causes were found in the stage of identifying the causes of deductions (Table 3).

| Theme | %Subtheme | Frequency of Repetition in Studies (Proportion), No. (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deductions related to service delivery | 1. Redundant requests (in the form of additional requests) | 41 (8.5) | (6, 9, 11-13, 15, 16, 18-20, 23, 24, 28-56) |

| 1.1. Request for more than three counseling sessions from a specialist or more than six counseling sessions for a specific patient | 7 (1.5) | (12, 19, 28, 29, 43, 47, 51) | |

| 1.2. Request for additional price for medicines | 11 (2.2) | (20, 35, 39-41, 51-53, 55, 57, 58) | |

| 1.3. Request for fees for services higher than approved tariffs | 12 (2.5) | (16, 20, 35, 39-41, 46, 51-53, 55, 56) | |

| 1.4. Additional request for consumables, medications, or surgery or anesthesia | 13 (2.7) | (12, 13, 15, 18, 20, 28, 31, 33, 34, 38, 40, 44, 55) | |

| 2. Request without a doctor’s order: Providing paraclinical services, such as examination, ultrasound, radiology, consultation, and electrocardiogram, for the patient in the absence of a doctor’s order in the patient record | 17 (3.3) | (12, 13, 15, 16, 20, 28, 31, 32, 36, 38, 40, 43, 47, 49, 51, 54, 55) | |

| 3. Lack of familiarity of medical personnel (i.e., doctors, nurses, and midwives) with the rules and regulations of insurance | 15 (3.5) | (11, 12, 24, 30, 33-35, 37, 39-41, 46, 48, 55, 56) | |

| 4. Lack of familiarity with new tariffs or lack of adherence to general regulations of tariffs | 10 (2.1) | (12, 19, 28, 29, 32, 33, 40, 42, 44, 48) | |

| 5. Visit by first- and second-year assistants | 2 (0.4) | (15, 18) | |

| 6. The consulting physician or respondent is not a specialist | 1 (0.2) | (15) | |

| 7. Physicians do not pay attention to revenue and insurance deductions | 5 (1) | (11, 12, 35, 37, 56) | |

| 8. Physicians’ excessive ambition, such as performing independent surgeries during other surgeries | 4 (0.8) | (12, 15, 40, 47) | |

| 9. Request for extra anesthesia hours | 14 (2.9) | (12, 13, 15, 19, 20, 34, 40-43, 47, 51, 52, 56) | |

| 10. Lack of commitment to adjustment codes in surgeries based on the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services” | 14 (2.9) | (12, 13, 15, 19, 20, 34, 40-43, 47, 51, 52, 56) | |

| Deductions related to service registration | 1. Registration and organizational errors (i.e., errors in calculating the cost of drugs and anesthesia) | 9 (1.9) | (9, 13, 18, 28, 36, 39-41, 55) |

| 2. Incorrect coding of service units (i.e., incorrect recording of k coefficient or incorrect coding of surgeries and anesthesia) | 11 (2.2) | (15, 16, 18, 31-33, 38, 40, 44, 50, 54) | |

| 3. Failure to register expensive medical supplies used in surgeries, such as prostheses, and failure to register the surgical site in operation notes | 4 (0.8) | (15, 18, 31, 48) | |

| 4. Failure to register or incomplete registration of the provided service (e.g., consultation and visit) in the patient’s file | 5 (1) | (13, 37, 39, 40, 43) | |

| 5. Failure to register or incomplete registration of drugs in the nursing report | 9 (1.9) | (9, 13, 18, 28, 36, 39-41, 55) | |

| 6. Repeated requests for drugs and services (e.g., request for two visits in one day, record sampling more than once a day, and repeated magnetic resonance imaging request) | 11 (2.2) | (15, 16, 18, 31-33, 38, 40, 44, 50, 53) | |

| 7. Frequent separate requests for consumable items | 4 (0.8) | (39, 40, 45, 55) | |

| 8. Failure to record the latest prices of drugs or services | 4 (0.8) | (18, 31, 38, 55) | |

| 9. Failure to record the insurance code correctly | 3 (0.6) | (28, 34, 42) | |

| 10. Failure to record services or incorrectly register them in the Hospital Information System | 12 (2.5) | (12, 13, 18, 24, 30, 34, 37, 40, 42, 44, 48, 53) | |

| 11. Incomplete documentation of the case, such as failure to record the date and time by physicians in the consultation sheet, ultrasound, and procedure | 27 (5.6) | (12, 18, 19, 24, 30-35, 37-47, 49, 51, 52, 54-56) | |

| 12. Incomplete, illegible, and undetailed registration of operation notes | 26 (5.4) | (9, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 31, 32, 36-45, 47-49, 51, 54-56) | |

| Deductions related to sending documents | 1. Defective documents and illegibility of documents, such as scrawl of prescriptions, drugs, services, and defective patient file | 14 (2.9) | (9, 12, 15, 19, 20, 32, 39-42, 44, 45, 47, 53) |

| 2. Incomplete and delayed submission of documents | 20 (4.2) | (9, 11, 12, 18, 19, 28, 32, 34, 36, 37, 40, 41, 43, 46-48, 51, 52, 55, 56) | |

| 3. Defects in the documentation of operation notes and anesthesia, such as not mentioning the date and time of the beginning and end of the operation and anesthesia notes | 16 (3.3) | (15, 16, 18, 31, 36-38, 40, 42, 43, 46-48, 54-56) | |

| 4. Lack of stamp and signature of the surgeon or anesthesiologist | 14 (2.9) | (15, 16, 18, 31, 36-38, 40, 42, 43, 47, 48, 54, 56) | |

| 5. Incomplete anesthesia chart and incomplete registration of drugs in the anesthesia description | 8 (1.7) | (15, 31, 36-38, 40, 42, 43) | |

| 6. Lack of stamp and signature of the treating physician in types of services (e.g., visit, radiology, consultation, and procedure) | 24 (5) | (12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 31, 36-45, 47-49, 51, 54-56) | |

| 7. Contradiction of the submitted documents with the services registered in the patient’s bill | 1 (0.2) | (38) | |

| 8. Billing for services not performed | 2 (0.4) | (39, 47) | |

| 9. Failure to send pathology sheets, incomplete pathology sheets, and delay in pathology response | 3 (0.6) | (15, 24, 47) | |

| 10. Lack of commitment and attention of senior management to the issue of deductions and hospital revenue, followed by weak supervision over the process of sending documents | 5 (1) | (11, 29, 37, 40, 55) | |

| Deductions related to the conversion of services into revenue | 1. Not covered by insurance (in services such as monitoring, some tests, and drugs) | 19 (4) | (12, 13, 19, 20, 24, 32, 35-40, 44, 46, 49, 50, 53, 55, 56) |

| 2. Non-compliance with insurance rules, such as prescribing medication outside the doctor’s specialty | 3 (0.6) | (15, 29, 40) | |

| 3. Providing surplus services outside the scope of the contract (e.g., consulting outside the tariff or non-compliance with general tariff rules) | 10 (2.1) | (12, 19, 28, 29, 33, 34, 39, 40, 44, 45) | |

| 4. Non-approval of the documents by the hospital insurance supervisor | 2 (0.4) | (40, 41) | |

| 5. Surgeries without the need for surgeon’s assistance and below 30 k | 4 (0.8) | (12, 15, 16, 47) | |

| 6. Contradiction between diagnosis and prescribed intervention | 6 (1.3) | (15, 32, 40, 51, 53, 54) | |

| 7. Contradiction of the book of relative health values with the directives of insurance organizations | 1 (0.2) | (18) | |

| 8. Disagreement between providers and insurers (due to the lack of specific insurance agendas and regulations and different implementations by insurers) | 5 (1) | (12, 15, 18, 48, 56) | |

| 9. Delay in sending letter sections by insurance organizations (due to poor interaction) | 4 (0.8) | (11, 12, 24, 37) | |

| 10. Changing the price of cases under non-global hospitalization to global ones | 1 (0.2) | (38) | |

| 11. Non-acceptance of hospitalization days (e.g., failure to calculate the correct number of beds, extra requests, and unrealistic calculation of the hoteling amount) | 10 (2.1) | (12, 16, 18, 19, 28, 31, 38, 40, 43, 47) |

Regarding frequency, three of the most common causes of the deductions were redundant requests, incomplete documentation of the case, and lack of stamp and signature of the treating physician in different services, respectively. Three of the least common causes of deductions were failure to pay attention to revenue and insurance deductions by the physician, visits by first- and second-year assistants, and non-approval of the documents by hospital insurance supervisors, respectively.

In this study, 35 solutions were extracted from different articles as solutions to reduce insurance deductions (Table 4).

| Theme | Subtheme | Frequency of Repetition in Studies (Proportion), No. (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies offered at the national level | - Modification of the document submission process in an electronic form | 2 (1.2) | (13, 40) |

| - Establishment of an efficient repayment system, such as a diagnosis-related group | 2 (1.2) | (40, 43) | |

| - Communicating and requiring the implementation of instructions in the same way and avoiding capricious behaviors of insurers | 3 (1.7) | (12, 13, 40) | |

| - Holding continuous courses to empower insurance agents and hospital revenue specialists | 2 (1.2) | (13, 50) | |

| - Timely informing insurance instructions and their changes to medical centers | 2 (1.2) | (13, 40) | |

| - Examining files before sending them to resident experts using the smart checklist | 2 (1.2) | (13, 40) | |

| - Familiarizing physicians with insurance rules and correct coding | 2 (1.2) | (12, 13) | |

| - Teaching the principles of documentation to all medical staff, physicians, and students | 6 (3.5) | (11-13, 40, 45, 50) | |

| - Creating a structure (i.e., formation of a deduction committee with the participation of all stakeholders [i.e., insurance, hospital, and university]) | 3 (1.7) | (11, 13, 40) | |

| - Monitoring the performance of physicians and medical staff and checking the errors in their documents | 2 (1.2) | (11, 40) | |

| - Continuous interaction between insurance companies and hospitals, correction of factors causing deductions, and communication of the list of services and drugs covered by insurance | 5 (2.9) | (11, 12, 40, 45, 50) | |

| - Improving the process of examining documents with measures, such as employing medical graduates to analyze and eliminate the shortcomings of the files | 1 (0.6) | (40) | |

| - Using a standard number of administrative/financial personnel to regulate the registration and auditing of files (e.g., secretary, discharge, and income) | 1 (0.6) | (13) | |

| - Continuous evaluation and timely delivery of evaluation results to the hospital (accreditation score: The basis for paying insurance to the hospital) | 2 (1.2) | (13, 50) | |

| - Improving the process of registering insurance deductions and equipping the HIS with alarms | 1 (0.6) | (40) | |

| - Considering financial penalties for physicians and medical staff responsible for the occurrence of insurance deductions | 3 (1.7) | (11, 40, 57) | |

| - Motivating providers to control deductions (with a variety of financial and non-financial incentives) | 3 (1.7) | (11, 40, 50) | |

| Strategies offered at the university level | - Holding training documentation workshops and the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services” for physicians, clinical staff, and revenue specialists | 12 (6.9) | (20, 24, 30, 34-37, 39, 47, 49, 51, 56) |

| - Establishing a suitable context by allocating an organizational chart for holding revenue and hospital audit | 5 (2.9) | (20, 34, 36, 37, 39) | |

| - Analyzing and reviewing documents before sending them to insurance organizations using a standard checklist | 5 (2.9) | (11, 20, 36, 37, 47) | |

| - Timely implementation of the instructions of insurance organizations | 2 (1.2) | (30, 37) | |

| - Necessity of prescribing medicines based on the obligations of insurance organizations | 3 (1.7) | (30, 34, 55) | |

| - Participation and cooperation of key individuals, such as management and leadership team, department officials, and physicians, in the hospital deduction committee | 1 (0.6) | (37) | |

| - Establishing a unified procedure between insurance organizations to apply deductions | 1 (0.6) | (24) | |

| - Motivating to control deductions in department secretaries, revenue specialists, and auditors using financial incentives | 4 (2.3) | (24, 37, 39, 52) | |

| - Cooperation of insurance agents to improve processes, training, and interaction between insurers and hospitals | 2 (1.2) | (24, 37) | |

| - Stability of employees of the revenue department (trained and fixed employees) | 2 (1.2) | (24, 39) | |

| - Establishing a single insurance system in the country and removal of insurance booklets | 1 (0.6) | (24) | |

| - Revising the repayment system by insurance organizations and establishing the diagnosis-related group reimbursement system | 5 (2.9) | (24, 34, 39, 51, 52) | |

| - Informing providers, such as physicians and midwives, of the list of services and drugs covered by insurance in a timely manner | 2 (1.2) | (35, 55) | |

| - Monitoring and providing feedback to wards, units, and individuals involved in insurance deductions and imposing financial penalties on individuals who make intentional mistakes | 3 (1.7) | (35, 37, 47) | |

| - Continuous evaluation of health centers regarding the frequencies and causes of insurance deductions | 1 (0.6) | (35) | |

| Establishing an active committee in the university headquarters to reduce hospital deductions (suitable substrate construction) | 1 (0.6) | (37) | |

| - Clarifying insurance rules and regulations for hospitals | 2 (1.2) | (20, 34) | |

| - Planning for the timely sending of documents to the revenue unit and then to insurance organizations | 2 (1.2) | (37, 39) | |

| - Using reminders and warnings in the HIS to reduce deductions | 2 (1.2) | (37, 47) | |

| Strategies offered at the hospital level | - Asking physicians to follow surgical and anesthesia coding rules | 1 (0.6) | (28) |

| - Preparing and approving specific and unit tariffs on drugs and medical supplies | 1 (0.6) | (28) | |

| - Establishing a quality control unit in the hospital for monitoring, teaching the principles of documentation, and checking the files using the failure modes and effects analysis technique | 3 (1.7) | (28, 48, 56) | |

| - Clarifying items covered by insurance (i.e., types of services, drugs, and medical supplies) by insurance organizations | 2 (1.2) | (28, 42) | |

| - Accuracy in registered prices of medicines and medical supplies | 1 (0.6) | (28) | |

| - Accurate calculation of the number of drugs and medical supplies | 1 (0.6) | (28) | |

| - Timely informing of insurance instructions to hospitals and timely implementation by them | 3 (1.7) | (29, 42, 46) | |

| - Holding meetings of the hospital deduction committee at the university headquarters and continuously monitoring the frequencies and causes of insurance deductions of affiliated hospitals | 1 (0.6) | (15) | |

| - Training staff in the field of admission instructions, proper registration of services, and insurance rules and instructions | 14 (8) | (9, 15, 18, 19, 29, 31, 33, 38, 42, 46, 48, 53, 54, 56) | |

| - Mechanizing the process of reviewing and auditing medical records | 6 (3.5) | (18, 29, 38, 43, 44, 46) | |

| - Establishing an expert team to review, refine, and modify documents before auditing by supervisors of insurance | 5 (2.9) | (9, 18, 19, 29, 53) | |

| - Continuous interaction between insurance organizations and the hospital for feedback, correction of deductions, and equalizing the codes not defined in the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services” | 9 (5.2) | (18, 29, 31, 38, 42, 43, 46, 48, 53) | |

| - Changing the method of reimbursement to hospitals from fee-for-service payment to a fixed method (e.g., Global) | 1 (0.6) | (42) | |

| - Upgrading HISs and registering deductions in them | 3 (1.7) | (43, 46, 52) | |

| - Preventing deductions due to visits (by registering a stamp and signature by the senior assistants or the treating physician during the usual visiting hours) | 1 (0.6) | (18) | |

| - Registering expensive medical supplies on operation notes | 1 (0.6) | (18) | |

| - Supervising the staff of the revenue unit by the hospital management and leadership team, providing continuous feedback, and providing financial rewards to them | 5 (2.9) | (15, 31, 32, 38, 53) | |

| - Employing experienced and specialized staff in the revenue and medical records unit | 4 (2.3) | (19, 31, 53, 54) | |

| - Establishing a link between volume, quality of work, and staff performance in controlling deductions and giving them financial benefits | 6 (3.5) | (19, 29, 31, 33, 43, 44) | |

| - Assigning part of the responsibility of financial management to the heads of inpatient wards, such as physicians and head nurses | 2 (1.2) | (15, 31) | |

| - Developing policies for using clinical guidelines and concluding contracts with physicians committed to complying with these guidelines | 2 (1.2) | (15, 31) |

Abbreviation: HIS, hospital information system.

In terms of frequency, three of the most common solutions to reduce deductions were training staff in the field of admission instructions, proper registration of services, and insurance rules, holding training documentation workshops for physicians, clinical staff, and revenue specialists, and continuous interaction between insurance organizations and hospitals, respectively. Three of the least common solutions to reduce deductions were improving the process of examining documents, timely implementing the instructions of insurance organizations, and upgrading hospital information systems (HISs) and registering deductions in them, respectively.

Table 5 shows a brief overview of strategies for reducing health insurance deductions by causal factors.

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Strategies for reducing insurance deductions related to providers | - Teaching the principles of documentation to all medical staff, physicians, and students |

| - Familiarizing physicians with insurance rules and correct coding | |

| - Monitoring the performance of physicians and medical staff and checking the errors in their documents | |

| - Asking physicians to follow surgical and anesthesia coding rules | |

| - Prevention of deductions due to visits (by registering a stamp and signature by the senior assistants or the treating physician during the usual visiting hours) | |

| Strategies for reducing insurance deductions related to the modification of processes | - Clarifying insurance rules and regulations for hospitals |

| - Assigning part of the responsibility of financial management to the heads of inpatient wards, such as physicians and head nurses | |

| - Establishing an expert team to review, refine, and modify documents before auditing by supervisors of insurance | |

| - Cooperation of insurance agents to improve processes, training, and interaction between insurers and hospitals | |

| - Participation and cooperation of key individuals, such as management and leadership team, department officials, and physicians in the hospital deduction committee | |

| - Monitoring and providing feedback to wards, units, and individuals involved in insurance deductions and imposing financial penalties on individuals who make intentional mistakes | |

| - Supervising the correct implementation of clinical guidelines and providing feedback in case of violations by the hospital management and leadership team | |

| Strategies for reducing insurance deductions related to the reform of policies | - Changing the method of reimbursement to hospitals from fee-for-service payment to a fixed method (e.g., Global) |

| - Planning for the timely sending of documents to the revenue unit and then to insurance organizations | |

| - Motivating providers to control deductions (with a variety of financial and non-financial incentives) | |

| - Continuous evaluation of health centers regarding the frequencies and causes of insurance deductions | |

| - Continuous interaction between insurance organizations and hospitals for feedback, correction of deductions, and equalizing the codes not defined in the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services” | |

| - Revising the repayment system by insurance organizations and establishing the diagnosis-related group reimbursement system | |

| - Stability of employees of the revenue department (trained and fixed employees) | |

| - Continuous interaction between insurance companies and hospitals, correction of factors causing deductions, and communication of the list of services and drugs covered by insurance | |

| - Timely informing insurance instructions and their changes to medical centers | |

| - Communicating and requiring the implementation of instructions in the same way and avoiding capricious behaviors of insurers | |

| - Holding continuous courses to empower insurance agents and hospital revenue specialists | |

| - Establishing a unified procedure between insurance organizations to apply deductions | |

| - Informing insurance providers, such as physicians and midwives, of the list of services and drugs covered in a timely manner | |

| - Developing policies for using clinical guidelines and concluding contracts with physicians committed to complying with these guidelines | |

| Strategies for reducing insurance deductions related to modification of infrastructure | Establishing an active committee in the university headquarters to reduce hospital deductions (suitable substrate construction) |

| - Using reminders and warnings in the HIS to reduce deductions | |

| - Examining files before sending them to resident experts using the smart checklist | |

| - Establishing the quality control unit in the hospital for monitoring, teaching the principles of documentation, and checking the files using the failure modes and effects analysis technique | |

| - Upgrading HISs and registering deductions in them | |

| - Using a standard number of administrative/financial personnel to regulate the registration and auditing of files (e.g., secretary, discharge, and income) | |

| - Modifying the document submission process in an electronic form | |

| - Establishing a suitable context by allocating an organizational chart for holding revenue and hospital audit | |

| - Mechanizing the process of reviewing and auditing medical records |

Abbreviation: HIS, hospital information system.

The strategies were divided into four categories, including strategies related to providers, modification of processes, reform of policies, and modification of infrastructure.

The present study was conducted to determine the causes of hospital deductions and identify strategies to reduce them in the last two decades. During this period, 41 studies examined the causes of deductions and provided solutions to reduce them in Iranian hospitals. Studies conducted on deductions in Iranian hospitals started in 2010, grew well within mid-2011 to 2015, and peaked in late 2020.

Insurance deductions might occur in all hospital departments and all stages of receiving service revenue, including providing services, registering services, submitting documents, and receiving revenues (9, 35, 37). Based on studies, additional requests for services (e.g., requests for more than three consultation sessions in a specialty or more than six consultation sessions in one case), requests for extra money for medications, requests for money for services more than approved tariffs, other additional requests (e.g., the number of consumables or medicines) (57, 58), and additional requests for surgery or anesthesia according to the stage of service were the most important causes of deductions in Iranian hospitals. This has been mentioned 41 times in the studies and is something that occurs in most hospitals and imposes great costs on them (6, 9, 11-13, 15, 16, 18-20, 23, 24, 28-56). Part of the reason for this problem might be the lack of familiarity of doctors and staff with insurance laws and regulations, and part of it is the financial incentive to increase revenues.

There are solutions to the above-mentioned problem, which were assessed in the present study at three national, university, and hospital levels and repeated 34 times in the studied articles. The solutions at the national level included familiarizing physicians with insurance rules and regulations and the correct way of coding, monitoring the performance of physicians and other medical staff and checking the errors in their documents, and correcting the deduction registration process. The solutions at the university level included establishing an active university committee (appropriate platform) to reduce hospital deductions, timely receiving of regulations and clarifying insurance instructions regarding deductions, and participation and cooperation of key individuals (i.e., management team, officials, and physicians) in the hospital deduction committee. The solutions at the hospital level included requiring physicians to comply with surgical and anesthesia codes, delegating part of financial management responsibility to heads of departments and units, such as physicians and head nurses, changing the method of payment from fee-for-service payment to a fixed-price agreement, and accuracy in the prices of imported items and medicines. Finally, equipping the HIS with alerts and reminders and providing feedback for deductions based on fee-for-service payment to staff and physicians are among the common solutions at the national, university, and hospital levels.

The results of a study by Coustasse et al. demonstrated that one of the most expensive and pervasive examples of fraud in providing medical care is upcoding. It occurs when a healthcare provider sends codes for conditions more critical than the patient has been diagnosed with in order to receive a higher refund. This type of fraud in 2015 was the cause of more than 60 billion dollars of overpaid claims by Medicare. The two solutions presented in this study were providing ongoing training to healthcare providers to avoid getting involved in the upcoding process and establishing a reward system to encourage whistleblowers to expose these types of fraud (59).

Other important causes of deductions related to the service registration stage were incomplete documentation of the case, such as lack of date and time registration by physicians in the consultation sheet, ultrasound, and procedure, and incomplete, illegible, and undetailed registration of operation notes, and registration of extra anesthesia hours. This cause has been repeated about 53 times in the studies and is one of the major causes of deductions in hospitals, especially teaching hospitals. The reason for this is the provision of services by assistants and medical students, their lack of familiarity with the correct principles of documentation, or even a lack of sufficient motivation among service providers to control insurance deductions. To solve this problem, solutions at the national, university, and hospital levels were considered in the present study.

The solutions to the above-mentioned problem were mentioned 44 times in the studies. These strategies at the national level included teaching the principles of documentation to all medical staff, physicians, and students, modifying the documentation process, and employing medical records to analyze and eliminate deficiencies in documents. In addition to holding training workshops for the target staff (i.e., physicians, clinical staff, and revenue specialists) to train to document and the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services”, analyzing and reviewing files before sending them to insurance organizations using a standard checklist and submitting documents to the revenue department and insurance organizations in a timely manner are among the solutions at the university level. The establishment of a quality control unit in the hospital for monitoring, teaching the principles of documentation, and handling cases using failure modes and effects analysis technique (60), forming an expert team to examine, refine, and review documents and provide feedback to individuals and departments before sending the documents to insurance organizations, and upgrading HISs and recording the deductions in them are among the solutions at the hospital level. Generating motivation to control deductions among department secretaries, revenue specialists, and service providers through financial incentives is a common strategy at the national and university levels.

A study in the United States demonstrated that some anesthesiologists estimated anesthesia times longer than the normal range to receive higher reimbursed expenses. The proposed solution of the aforementioned study was changing the payment policy. Based on this solution, the payment to anesthesiologists is based solely on the type of case (and removing the element of time). Under the new policy, anesthesiologists will no longer be paid based on the length of time they report. Instead, similar to surgeons, anesthesiologists are allowed to add a modifier code for particularly difficult cases. Another potential policy is to consider anesthesia time based on the duration of surgery, for example, the time the patient enters and leaves the operating room, which is usually recorded by a third person (i.e., operating room personnel) (61).

In support of the above-mentioned findings, the results of a study by Drabiak and Wolfson in Florida, United States, showed that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services classified billing fraud and abuse into four categories, namely (1) errors that lead to administrative errors, such as incorrect billing; (2) inefficiencies that cause waste, such as ordering too many diagnostic tests; (3) deviations and abuses of the laws, such as updating claims; and (4) intentional and deceptive fraud, such as billing for services or tests that are not provided or are undoubtedly medically unnecessary. In this study, training in the residency program was declared to be the most basic proposed solution to reduce fraud and abuse, and its implementation was considered one of the most important duties of heads of universities of medical sciences, heads of departments, and managers and supervisors of departments (62).

Other causes of deductions are related to the service registration stage, which have been repeated about 65 times in the studies and included incorrect coding of service units (i.e., incorrect registration of k coefficient or incorrect coding of surgeries and anesthesia), failure to register expensive equipment used in surgery, such as prostheses, or failure to record the surgical site in operation notes, registration and organizational errors (i.e., false calculation of the cost of drugs and anesthesia), failure to register or incorrectly register services in the HIS, and registration of repeated requests for drugs and services (e.g., requests for two visits in one day, registration of sample collection more than once a day, and repeated requests for magnetic resonance imaging). The lack of familiarity of surgeons and anesthesiologists with coding issues and the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services” or financial incentives to increase revenue is one of the most important reasons for this problem. Overall, the solutions to eliminate this shortcoming have been mentioned 24 times in studies. At the national level, the solutions included familiarizing physicians with insurance laws, the tariff book of “Relative Values of Health Services”, and proper coding and monitoring of how they act in this regard.

At the university level, the solutions included continuous evaluation of health centers regarding the frequencies and causes of deductions. Finally, the solutions at the hospital level included appropriate and ongoing interaction between insurance organizations for feedback and correction and equalization of codes not defined in the “Relative Value of Health Services” book. The solutions proposed in a study by Fakhry emphasize the necessity of continuous training of physicians, staff, and surgical assistants in order to be fully acquainted with the principles of documentation, correct coding, and issuance of appropriate bills and acknowledge that continuous education leads to higher efficiency and revenue, in addition to reducing the unfavorable results during the audit of documents (63). Nevertheless, a study by Benke et al. demonstrated that providing short-term training (90 minutes) for ear, nose, and throat surgical assistants does not have similar results for everyone. Assistants who had no previous experience in the issuance of bills or coding made significant progress in these two skills after a short-term training program in comparison to assistants who did coding and issuance of bills regularly (64).

In addition to using reminders and warnings in the HIS, the evaluation of the reimbursement system by insurance organizations, such as establishing a diagnosis-related group (DRG) system, has also received special attention as a common solution in studies conducted at the national and university levels. In support of this, it is possible to refer to a study by Widmer in Switzerland, which showed the increase in efficiency in hospital costs as one of the benefits of prospective payments, such as DRG, compared to retrospective payments (65). Moreover, based on the results of a similar study conducted by Panagiotopoulos et al. in Greece, the DRG payment system enables us to know the actual cost of hospitalization and can help create a cost database over time in hospitals or specific clinical departments (66).

The most important causes of deductions in the document submission stage, which were repeated 58 times in studies, included the absence of stamp and signature of the treating physician in various services (e.g., visit, radiology, consultation, procedure, and description of anesthesia and operation) and delayed submission or incomplete submission (e.g., without patient details and records, without a date, or with a wrong date). The solutions to eliminate these shortcomings have been considered in studies conducted at national, university, and hospital levels and were repeated 21 times. The solutions at the national level included using a standard number of administrative and financial personnel to prepare, register, and audit files (e.g., secretary, discharge, and revenue) and modifying the document submission process (i.e., online submission). On the other hand, scheduling to send documents to the hospital revenue/discharge department in a timely manner and their timely submission to insurance organizations, creating a structure and chart for human resources for the discharge department and audit department of hospitals in order to employ related graduates, stability of the staff of revenue department and discharge department of hospitals (having trained fixed-term staff), cooperation of representatives of the insurance organization for education and modification of processes, and active and two-way communication between insurance companies and hospitals are some of the strategies that have been mentioned in the studies conducted at the university level.

Mechanization and systematization of auditing and reviewing medical records and preventing visit deductions by having the stamp and signature of senior assistants or physicians during normal visiting hours are among the solutions at the hospital level. In confirmation of the aforementioned solution, a study by Adams et al. dealt with the consequences of sending medical bills with missing, incomplete, and incorrect information, failure of Medicare to pay physicians’ claims, loss of revenue, financial penalties, tracking possible fraud, and disqualification from participating in government programs. In the second part, the study provided solutions to assess the potential risk of improper billing and improve the financial management of medical bills (67).

Finally, most important causes of deductions in the stage of receiving revenues, which have been repeated about 55 times in the studies, included non-commitment of insurance companies to cover some drugs or services, such as monitoring and certain tests, non-compliance with insurance regulations, such as prescribing drugs outside the doctor’s specialty, providing surplus services and outside contract (e.g., consultations outside the defined tariffs and non-compliance with general tariff regulations), non-approval of documents by the relevant official, discrepancy between diagnosis and prescribed intervention, disagreement between providers and insurance companies (due to a lack of specific insurance agendas and regulations and different implementation by insurance companies), delay in sending directives by insurance companies (due to poor interaction), and non-acceptance of hospitalization days due to the incorrect calculation of beds, extra requests, and unrealistic calculation of hospital hoteling cost.

The most important solutions were repeated 36 times in the studies at three national, university, and hospital levels. The solutions at the national level included continuous interaction between insurance companies and hospitals in order to correct deductions, notification of the list of services and drugs covered by insurance, timely notification of instructions and changes to medical centers, uniform implementation of guidelines, prevention of capricious behaviors of insurance companies, holding continuous training courses to empower insurance agents and hospital revenue specialists, and creating a suitable structure and platform to reduce deductions (i.e., forming a deduction committee with the participation of all stakeholders [i.e., insurance companies, hospitals, and respective universities]).

Strategies in the studies conducted at the university level included creating a unified procedure between insurance organizations in applying deductions, participation and cooperation of key individuals (i.e., management team, department officials, and physicians) in the hospital deduction committee, continuous monitoring, and providing feedback to the departments and individuals involved in deductions. In confirmation of the aforementioned finding, a study by Alinia and Davoodi Lahijan indicated that the integration of several health insurance organizations could be a crucial policy in solving some insurance challenges and problems because it solves the problem of the difference between the basic insurance organizations for applying deductions and the difference in the covered service packages forever (68).

On the other hand, common solutions considered in the studies at both university and hospital levels included informing providers (i.e., doctors and midwives) of the list of services and drugs covered by insurance, holding meetings for reviewing hospital deductions at the university level, and continuous monitoring of affiliated hospitals (i.e., creating a suitable platform for controlling deductions and increasing hospital revenue). Finally, the solutions at the hospital level included developing policies for the use of clinical guidelines and concluding contracts with committed physicians in this field, monitoring and follow-up by the hospital management team on the implementation of clinical guidelines, giving feedback about deductions to those who cause them, and upgrading HISs and recording the deductions in them.

Numerous studies have highlighted the important role of the HIS in reducing deductions and improving the financial management of a complex hospital organization. Comprehensive HIS, if used by trained users, can be a good platform for the effective use of human and financial resources and reduce insurance deductions in hospitals as it records all provided services and provides the possibility of defining services based on insurance laws and clinical guidelines and of course the possibility of reporting the provided services. Improving the quality of medical documentation is one of the most important benefits of using the HIS, and one of the most obvious consequences is controlling and reducing deductions in healthcare centers, which is confirmed by a study by Howard in UK Health Care (69). Helmons et al. also acknowledged in his study that electronic health service registration systems could be beneficial in reducing the excessive use of medications and their costs (70).

4. Conclusions

This scoping review identified the research gap in the proposed solutions to reduce insurance deductions, especially how to upgrade the HIS or equip such systems with warnings and reminders in hospitals. The results of this study can be used by hospital managers, insurance companies, policymakers, and health researchers as a basis for evidence-based decisions in the field of hospital deductions. In the course of expanding the knowledge of how to control hospital deductions, this can be a new approach that provides innovative solutions that received less attention in previous studies.

Overall, the strategies to reduce deductions are presented in four main themes, including provider-related solutions, process-related solutions, policy-related solutions, and infrastructure-related solutions. Most of the solutions belong to the theme of policy reform and include changing the policy of hospitals reimbursement, proper and continuous interaction between insurance companies and hospitals, empowering insurance agents and hospital revenue specialists, timely submission of documents, and motivating clinical and administrative staff to control deductions using financial incentives. Undoubtedly, solving the problem of deductions in a bureaucratic organization, which is very complex and multidisciplinary in a hospital, is a very complex matter and requires multifaceted cooperation and synergy of different organizations and stakeholders. Currently, due to the wide application of machine learning methods as a subset of artificial intelligence in various industries, this science can be used in the health industry, especially in financial resource management. Part of the tasks of human resources in auditing and processing the documents of hospitals can be delegated to machines.

4.1. Limitations

It was difficult to find a suitable term for “deduction” in English databases since it has no exact equivalent word in English.