1. Context

Economic sanctions are often viewed as a humane alternative to warfare. A sanction is a penalty or punishment imposed on a country, organization, or individual to enforce compliance with a law, rule, or regulation. Sanctions can take various forms, such as economic restrictions, trade limitations, diplomatic measures, or military actions (1). However, they often result in human suffering in addition to the desired change in the political behavior of target countries (2). Forced migration, displacement, brain drain, and economic collapse are some of the most adverse consequences of sanctions on affected countries. A growing body of literature argues that economic sanctions detrimentally impact public health and human well-being (3-5) and cripple healthcare systems (6-9).

Economic sanctions affect the medicine market (1) and cause increased suffering and death among the population, particularly vulnerable groups like women, children, people with rare diseases, the elderly, veterans, and marginalized communities (10, 11). Sanctions also contribute to an increase in vaccine-preventable outbreaks, expanding epidemics of infectious diseases, mental health disabilities, and mortality rates among vulnerable groups (12-15).

Although political and economic sanctions against Iran have been in place over the past four decades, there are two crucial episodes in terms of their consequences: multilateral economic sanctions (imposed by the UN, EU, and the US) from December 2006 to January 2016 and unilateral economic coercion (imposed by the US) from August 2018 to date. These two sanction episodes have had significant adverse effects on the healthcare system and public health (7). Since February 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Iran’s healthcare system has been doubly burdened, and the adverse effects of sanctions have accelerated (16).

Public health has primarily been affected by the reduction of government healthcare expenditure (17) and the significant decline in market availability and access to life-saving and essential medicines (18-23). Furthermore, specific diseases, such as cancer, rare diseases, and mental health disorders, have been more severely impacted by sanctions compared to other health problems (24-28).

Considering the impact of economic sanctions on other countries, it can be inferred that the sanctions imposed on Iran in the last decade have significantly affected both population health and the healthcare system. Consequently, conducting a thorough investigation becomes imperative to offer a comprehensive understanding of the magnitude and trajectory of these effects over time. To achieve this objective, a concurrent embedded mixed-methods study has been devised to evaluate the impact of economic sanctions on Iran's population health and healthcare system.

In the quantitative part, we will elucidate the impact of sanctions on health using 28 indicators over a 20-year period (between 2000 and 2020) at both national and sub-national levels. Meanwhile, the qualitative aspect of our study will explore the pathways through which the effects of sanctions occurred. In this part of the study, we aim to delve into the perceptions and experiences of the public regarding the short- and long-term health implications of living under sanctions and identify the health policymakers' opinions regarding the impact of sanctions on the health system. During the interpretation phase, we'll compare findings from both quantitative and qualitative analyses. Moreover, the findings and conclusions will be thoroughly examined, accompanied by detailed explanations of the diverse mechanisms through which various sanctions can impact health outcomes.

1.1. Project Summary

Integrating complementary qualitative and quantitative approaches in a concurrent embedded mixed-methods study (29) allows us to develop a comprehensive understanding of the complex issues surrounding the public health impact of economic sanctions. Quantitative and qualitative data will be collected simultaneously and analyzed separately. We will compare results from these two parts of the study to draw overall conclusions.

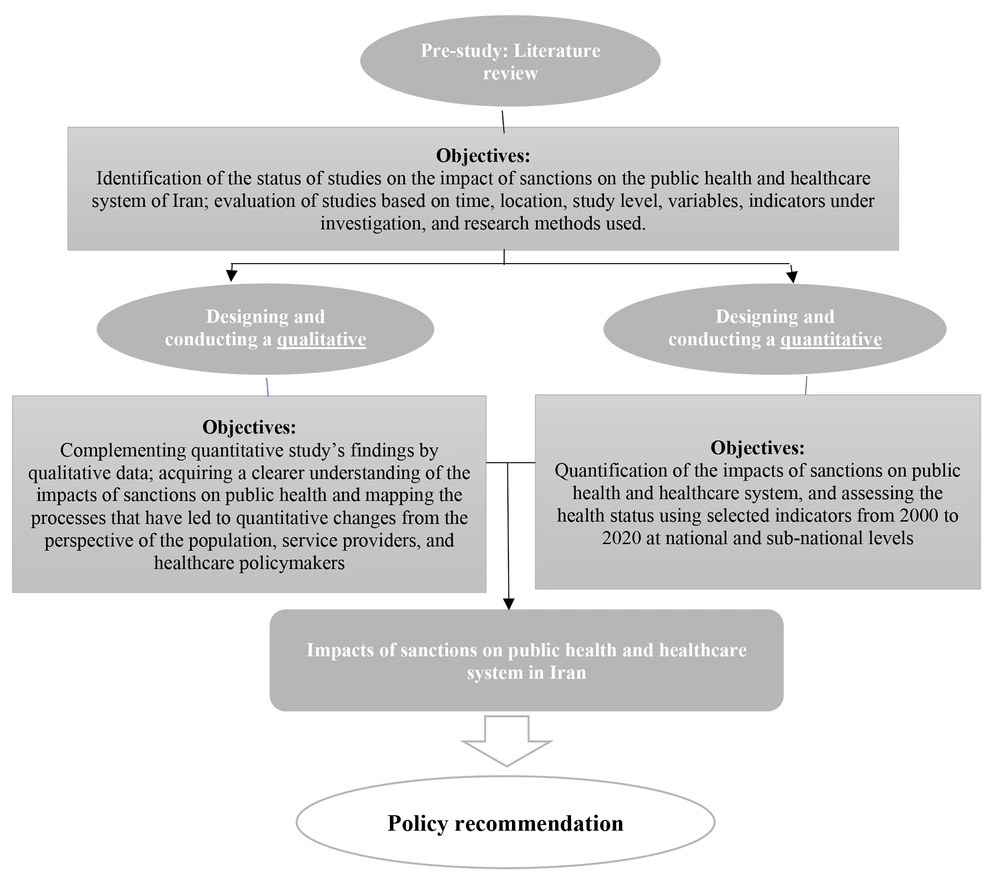

The quantitative part of the study investigates the effects of economic sanctions on the healthcare system and population health in Iran at the national and sub-national levels from 2000 - 2020. In the qualitative part, we will explore the perceptions and experiences of health professionals, policymakers, and industry managers regarding the public health impact of economic sanctions on Iran. Additionally, a selected group of patients suffering from chronic and rare diseases will be interviewed to explore their perceptions and experiences of the impact of sanctions on their health and disease condition. Figure 1 shows a summary of the aims of the two parts of this study.

1.2. Setting

Iran is a country in West Asia affiliated with the Eastern Mediterranean region of the World Health Organization (WHO). It spans an area of approximately 1.64 million square kilometers and has an estimated population of 87.92 million (2021). The MoHME oversees the health system in Iran, operating through a comprehensive network of over 70 universities of medical sciences (UMSs) across 31 provinces. Life expectancy at birth in Iran was recorded as 75 years in 2020 (30). Read more about the health system indicators of Iran at the World Health Organization's Global Health Observatory (31).

2. Methods

This mixed-methods study pertains to the field of health system management and spans the period from 2000 to 2020, covering both national and sub-national levels between 2019 and 2022. The study is structured into two phases: A qualitative study, a quantitative study, and a literature review (as a pre-study) (Figure 1).

2.1. Quantitative Study Methodology

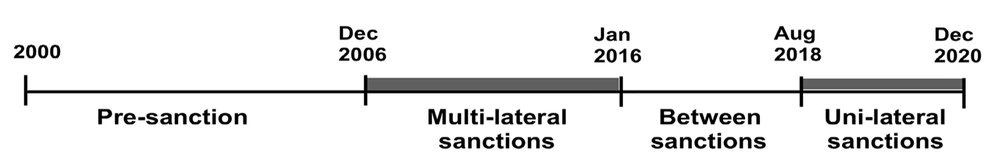

The study period (2000 - 2020) encompasses two significant episodes of economic sanctions in Iran's recent history: Multilateral sanctions (senders: UN, EU, the US) from December 2006 to January 2016, and unilateral economic sanctions (sender: The US) starting in August 2018 (Figure 2). Additionally, it includes a two-and-a-half-year sanction-free interval (February 2016 - July 2018). Although international sanctions began affecting Iran from 2006, their full impact on various transactions was more pronounced later. Therefore, we consider 2010 to 2016 as the first analytical episode of sanctions for our study. Data from before 2010 will serve to understand pre-sanction trends and form the baseline scenario.

2.2. Study Variables

The process of variable selection was carried out in three steps: Literature review, data sources review, and expert consensus stage (Table 1). We began with a comprehensive literature review from 2000 to 2020 to identify how economic sanctions could affect population health and measure these effects. We searched international databases such as PubMed/Medline, Social Sciences Database, and Google Scholar. We included studies published in English and different health system contexts, such as hospitals, healthcare centers, and international comparisons. Regarding the effect of sanctions on health, all studies assessing this topic through descriptive analysis, systematic review, and analytical studies were included.

| Variable Selection Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Literature review | - Study period: 2000 - 2020- Databases: PubMed/ Medline/ Scopus- Key words: Sanction*, Economic sanction*, Health*, Medicines*, Variables*, Indicators*Included criteria: Subject, year, English & Persian language |

| Step 2: Database review | We searched national and international databases, i.e. various disease registration systems, hospital and pharmaceutical resource registration systems, mortality registration systems, etc., and identified the variables and indicators with available data for the study years, both at the national and provincial levels. |

| Step 3: Expert panel | Through expert panel discussions, which included scientific advisors and members of the study team, we assessed the importance of each variable based on the study objectives and their significance for policymakers. |

Steps and Process of Selecting Variables

After organizing the findings, we extracted relevant indicators. We reviewed the data for each indicator and the reliability of the data sources by checking electronic databases, the MoHME, and the World Health Organization's Global Health Observatory. This process helped us determine the final measurable indicators for which data was available.

Finally, we reviewed all indicators through a series of meetings with experts, including researchers and established policymakers in management and health economics. The panel discussed each indicator's necessity and importance based on the study objectives and their priorities for policymakers. Through consensus, the study's final indicators were determined. We developed identifiers for each indicator, including definitions, data collection methods, and calculations (Table 2).

| Duration: 2000 - 2020Level: National–Subnational | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicators | Definition | Data Source |

| Macroeconomic indicators | ||

| Gross domestic product (GDP) | Total value of goods and services produced in a country and measured annually | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Unemployment rate | Share of workers aged 10 or older in the labor force who do not currently have a job but are actively looking for work. | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Inflation rate | Average price change in a basket of commodities and services over time. Inflation is measured in percentage and indicative of the decrease in the purchasing power of a unit of a country's currency. | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Health inflation rate | Average price change in a basket of health care services over time | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Healthcare resources indicators | ||

| Current health expenditure (CHE) per capita in PPP into$ | Average expenditure on health per person in comparable currency including the purchasing power of national currencies against USD | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Household expenditure as percentage of CHE (%) | Average expenditure on health as percentage of CHE (%) | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Hospital beds (per 10 000 population) | Number of hospital beds available per every 10, 000 inhabitants in a population | Statistical Centre of Iran |

| Households impoverished by out-of-pocket payments (%) | Households pushed below or further below a relative poverty line (reflecting basic needs: Food, housing, utilities) by out-of-pocket payments (%) | Statistical Centre of Iran,WHO and Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME) |

| Household’s catastrophic health expenditure (%) | The proportion of households with catastrophic health spending defined as out-of-pocket payments greater than 40% of capacity to pay for health care. Capacity to pay for health care is defined as total household consumption minus a standard amount to cover basic needs (food, housing and utilities). | Statistical Centre of Iran,WHO and MoHME |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure as percentage of CHE (%) | Share of out of pocket payments of total current health expenditures | Statistical Centre of Iran,WHO and MoHME |

| Accessibility of medicine | We consider several data item to show accessibility of medicine:- Annual diabetes medicine sales (int$, PPP)- Annual cancer medicine sales (int$, PPP)- Annual multiple sclerosis medicine sales (int$, PPP)- Annual Hemophilia medicine sales (int$, PPP)- Annual Thalassemia’s medicine sales (int$, PPP)- Annual Hemodialysis medicine sales (int$,PPP) | The national pharmaceutical sales statistics database |

| Health Outcome indicators | ||

| Neonatal mortality rate | Number of deaths during the first 28 completed days of life per 1000 live births in a given year or other period | Ministry of Health and Medical Education |

| Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) | Number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period | World Health Organization |

| Under-five mortality rate | Probability (expressed as a rate per 1000 live births) of a child born in a specific year or period dying before reaching the age of five years, if subject to age-specific mortality rates of that period. | Ministry of Health and Medical Education |

| Mortality due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) | Age-standardized mortality rate attributed to NCD (per 100,000 population). The four main NCDs are cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes, and chronic lung diseases. | Ministry of Health and Medical Education |

| Mortality due to rare diseases | A rare disease is any disease that affects a small percentage of the population; Age-standardized mortality rate attributed to rare diseases (per 100,000 population) | Ministry of Health and Medical Education |

| Neonatal mortality rate (NMR) | Death registration system in MoHME / Global health observatory of WHO | |

| Under-five mortality rate | ||

| Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | Death Registration System of the MoHME | |

| Hypertension mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Myocardial infraction mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| COPD mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Diabetes mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Multiple sclerosis mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Thalassemia mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Stroke mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Brain tumor mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Leukemia mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Lung cancer (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Colorectal cancer mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Gastric Cancer mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Prostate Cancer mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Breast Cancer mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Total cancer mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||

Definition of Study Variables

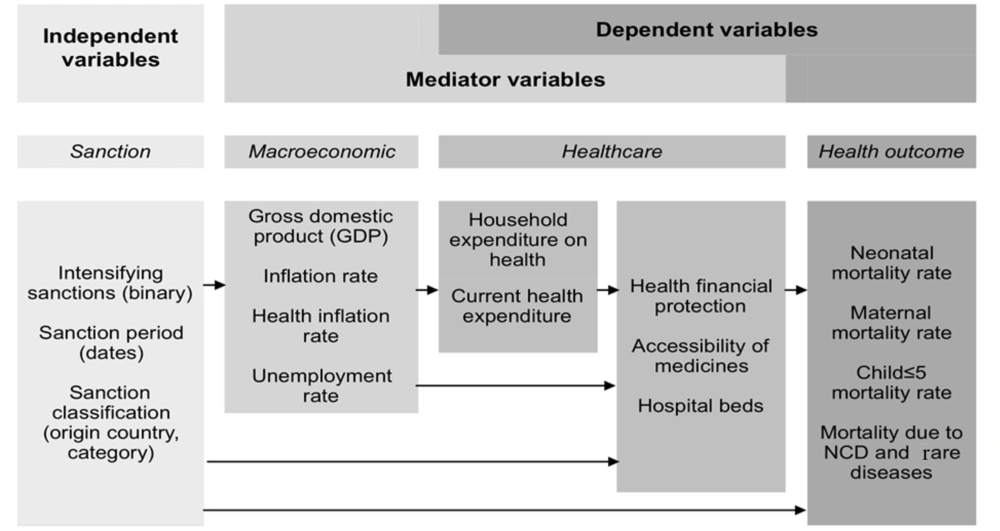

Based on the identified variables, a primary model has been hypothesized to present the impact of economic sanctions on population health and the healthcare system in Iran (Figure 3). This model illustrates each dependent, independent, and mediator variable, along with their hypothetical relationships.

2.2.1. Independent Variable

The primary independent variable in this study is the presence of economic sanctions. We consider sanctions as a time-varying variable, taking values between 0 and 1 (inclusive). A value of 0 indicates no sanction action, 1 indicates a sanction is fully enacted for the year, and 0.5 represents periods between sanctions.

2.2.2. Dependent Variables

Economic sanctions impact population health through various pathways. Based on the process of variable selection demonstrated in the previous section, we considered a set of health-related indicators most likely affected by economic sanctions as dependent variables. These include health outcomes such as the under-five mortality rate and mortality due to non-communicable and rare diseases.

2.2.3. Mediator Variable

Alongside or unrelated to economic sanctions, numerous covariates can describe underlying mechanisms that link economic sanctions to health-related outcomes (mediators) or determinants of health-related outcomes unrelated to sanctions (moderators). A possible pathway in which the covariates could have a mediating role in the model is shown in Figure 3. In the modeling section, we address how to provide a causal inference of the effects of sanctions on the study outcomes in the presence of other covariates.

Generally, the covariates are categorized into several subgroups, including macroeconomic variables, healthcare resources, UHC Index, medicines, and nutritional variables. Sanctions are assumed to influence economic variables such as gross domestic product, inflation rate, and unemployment rate. Economic indicators mediate the influence of sanctions on healthcare indicators and public health. This study’s healthcare indicators consist of financial issues such as current health expenditure and household expenditure on health, and healthcare utilization by assessing hospital beds and accessibility of medicine. Accessibility of medicines is crucial because it is directly affected by economic sanctions due to international trade restrictions.

2.3. Data Collection Method

The data collection process is expected to span nine months. For national-level data collection, we will start by identifying the relevant data sources. Subsequently, data extraction will be carried out, considering the platform available for each source. Formal communication with data-holding organizations will be established to introduce the study and share its ethical code, seeking collaboration. In cases where data is derived from statistical yearbooks, manual entry of data into Excel format will be undertaken. For acquiring data from international sources, the procedure entails logging into the system and selecting the desired indicator. Following this, the unit of measurement for the indicator and the necessary years will be meticulously documented to facilitate data extraction in diverse formats. In this investigation, data will be extracted in Excel format. The data pertaining to each variable will undergo a comprehensive review by the research team. After this scrutiny, a determination will be reached regarding the selection of the most appropriate data source to serve as the study's baseline.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Tool

The initial step involves entering all collected data into Excel sheets, adhering to the specific format of each database due to the diversity of databases and data types. Following this, a custom checklist will be created to systematically gather and organize the accumulated data.

2.5. Data Management

To address insufficiencies in the collected data and ensure compatibility with statistical models, a meticulous data cleaning process will be executed. This process will utilize the "tidyverse" and "Amelia" packages within the R-4.2.1 software, ensuring thorough and accurate preparation of the data for subsequent analysis.

Outlier data management will be conducted in two phases. The first phase occurs before model fitting and aims to identify anomalies resulting from registry errors. Any detected issues will be addressed through revision or omission. Following the statistical model fitting, a second phase of outlier identification will be carried out through residual tests.

Addressing missing data poses another challenge during the pre-processing step. The "Amelia" package within the R-4.2.1 software will be employed for effective handling of missing data.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We will use "change point regression" (JPR) for impact assessment as the main analysis to test the study hypothesis regarding the impact of sanctions on health indicators. "Mediation analysis" will also be employed to confirm shifts in trends and quantify the relationships between sanctions and variables.

Change point regression: Also known as segmented regression or piecewise regression, JPR is a statistical technique used to analyze relationships between variables when there is a change in the slope of the relationship at a specific point, known as the joint point. JPR allows us to identify and estimate the location of the joint point, as well as the slopes of the regression lines before and after the joint point. The joint point represents the point at which there is a significant change in the indicators being studied, due to factors such as an intervention, policy change, or natural occurrence. Our assumption is that the sanction could make changes to the health indicators in this study.

Specifically, it can be used to test our hypothesis regarding the occurrence of joint points after 2009 (the initiation of the first period of sanctions). The aim of the present study is to investigate the evidence supporting a deterioration in public health trends following the commencement of the first period of sanctions.

For this study, only one joint point will be considered for public health trends. Consequently, our model will comprise two separate regression equations, one for the period before the joint point and another for the period after it:

In which yt represents a public health index and βij are regression coefficients in the model’s j section. β01 and β02 represent the average of yt (logarithm) before and after the join point C0, respectively. β12 also signifies the direction of the yt trend after C0 time. If β12 > 0 after C0, the trend of yt is ascending, while if β12 < 0, it is descending. To control the lag-time effect on yt changes, φij was entered into the model. εt is the model’s random error, and εt ~ N (0,σ2).

Generalization of join point regression model for panel data at sub-national level: If sub-national level data for a given index yt is available, random-effects modeling is used to estimate its join point in each province.

In this equation, δk ~ N (0,σc2). Therefore, C0 and Ck are estimates of the national and sub-national level join points, respectively, and δk represents the impact of province K on the join point.

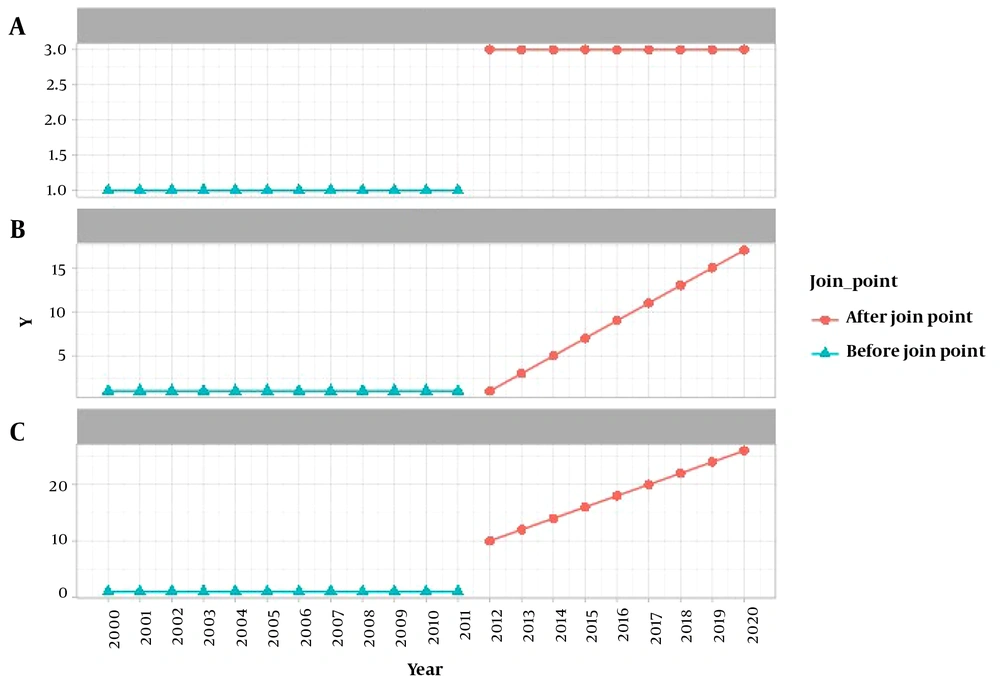

Study hypotheses and statistical inference: Using model (1), three scenarios can be identified for the changes in upward trends of public health after 2009 (Figure 4). The presence of a join point after 2009 for the hypothetical index Y is evident in all scenarios. Figure 4-A depicts a scenario in which the average of Y is higher only before and after the join point. Figure 4-B illustrates a scenario in which Y exhibits an upward trend after the join point, and Figure 4-C presents a combination of scenarios A-1 and B-1. In the C-1 scenario, apart from the higher average of Y after the join point, its trend also ascends following the join point.

To identify the illustrated scenarios in Figure 4 using model (1), the following hypotheses should be tested. First, the hypothesis for the presence of a join point at Y after 2009 is tested as follows:

To determine the presence or absence of a join point, "cp_1" is examined in the model's outcomes. If its infimum is less than 2009 (the infimum and supremum indicate that changes occurred in a previous year, not in 2009), then hypothesis 0 is accepted, and hypothesis 1 is rejected (indicating there is no join point in 2009). If there is indeed a join point in Y's trend after 2009, taking into account the rejection of hypothesis 0 in tests (3) and (4), the changes in Y's trend that occur after the join point can be estimated based on one of the scenarios presented in Figure 4:

If only test (3) rejects hypothesis 0, it can be concluded that Y's trend changes align with the A-1 scenario. If only test (4) rejects hypothesis 0, the changes align with the B-1 scenario. If both tests reject hypothesis 0, Y's trend changes correspond to the C-1 scenario.

To determine whether hypothesis 0 is accepted or rejected in tests (3) and (4) and to identify which scenario the trend changes follow:

- In test (3), “int_2 - int_1 > 0” (β02 – β01) is examined: If both infimum and supremum are positive, hypothesis 0 is rejected, indicating that the average for the selected index has increased before and after the join point.

- In test (4), “sigma_1” (β12) is assessed; if neither the infimum nor the supremum includes 0, hypothesis 0 is rejected, indicating that the selected index has undergone an ascending trend after the join point.

2.7. Computer Calculations

Statistical calculations will be done using the “mcp” packages in the R-4.2.1 software. Statistical deductions within “mcp” packages will be conducted using the Bayes method. A non-informative prior distribution will be considered for our parameters and the posterior distribution mean will be used as the point estimate for model parameters (1). In addition, 0.5 and 0.95 posterior distribution percentiles will be used to report credible intervals.

2.7.1. Mediation Analysis

Mediation analysis will be employed to confirm shifts in trends and quantify the relationships between sanctions and variables. These models allow for the measurement and estimation of direct and indirect effects, utilizing a mediator variable like the health sector inflation rate, on the health outcome variable. In the mediation analysis, the dataset will undergo two concurrent regression models. The primary regression model will focus on gauging the impact of sanctions on mediator variables, specifically macroeconomic indicators and healthcare resources. Simultaneously, the second regression model will quantify the influence of these mediator variables on the health outcome variable. The ensuing results of the mediation analysis will illuminate both the direct and indirect repercussions of sanctions on health outcome indicators. The General Additive Mixed Effect Model (GAMM) will be utilized for mediation analysis in this study, as it can measure complex functional relationships among other covariates and outcome variables. The mediation analysis will be conducted using the "medflex" and "mgvc" packages of the R-4.2.1 software.

2.8. Quality Assurance

As outlined in the preceding sections, our approach involves utilizing standardized data collection tools, validating measurement instruments, and strictly adhering to established research protocols. To mitigate selection bias, we will employ a census approach, utilizing panel data at both the national and subnational levels. Comprehensive training will be provided to data collectors to ensure the accuracy of data collection, while strategies will be implemented to minimize the occurrence of missing or erroneous data. Quality control measures will include data validation checks, assessments of inter-rater reliability, and systematic procedures for addressing outliers or data discrepancies, all aimed at enhancing the overall quality of the data collected.

A limitation of this study is demonstrating the impact of sanctions on health indicators, which may present a challenge, and it may not be possible to find a direct relationship between them. We will attempt to demonstrate the existence of this relationship by introducing other mediating variables, such as economic indicators and health system resource variables.

2.9. Qualitative Study Methodology

Content analysis with an inductive approach will be used in the qualitative part of the study. Designing and conducting the study is expected to take 12 months.

2.9.1. Participants

Participants will be classified into two groups:

1) Patients: This group includes patients covered by Iran’s Health Insurance Organization (IHIO) with a chronic or rare disease diagnosis from selected provinces based on their level of development. These provinces include Tehran (the most developed province), Sistan and Baluchistan (the least developed province), Hamedan, and Yazd (developing provinces). Patients will be randomly chosen based on phone numbers provided by IHIO.

2) Health policymakers and experts: Participants in this group will be selected using purposive sampling. Selection criteria will include theoretical familiarity with sanctions in the healthcare sector, cooperation in decision-making processes related to resource allocations or clinical expertise related to rare diseases, knowledge of national macro policies and plans, awareness of sanctions' impacts on public health, interest in the study, and consent to participate.

2.10. Data Collection Tool

Semi-structured interviews using interview guides will be conducted. Two thematic guides will be developed according to the participants and study aims, based on the opinions of the study's scientific advisors.

2.11. Data Collection Method

Interviews will be conducted as follows:

Patient interviews will be conducted over the phone. Interviewees will introduce themselves, be briefed on the study, and after ensuring privacy and obtaining consent to participate and record, the interview will proceed or move on to the next patient. Questions will be tailored to the social status and literacy levels of the interviewees, with no pressure exerted on them to answer certain questions. The average interview duration for this group is expected to be 20 minutes.

Health policymakers and experts will be interviewed in person, following initial introductions over the phone. After setting the interview date and obtaining consent to participate and record, the interviews will take place. The recorded sessions will be transcribed and sent for confirmation and consent for analysis and publication. The average interview duration for this group is expected to be 35 minutes.

Interviews and data collection will continue until data saturation is achieved.

Participants' agreement to participate in this study will be obtained after a thorough explanation of the research purpose and process. All participants will be given adequate time to read the information sheet containing further explanations and decide whether they want to participate in this study. They will be required to sign the informed consent form before the interview. Additionally, data collection will be coordinated with the authorities. Participants' confidentiality will be preserved by not revealing their identity during data collection, analysis, and reporting of the study findings.

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

In the data analysis phase, content analysis using an inductive approach will be conducted. Content review and coding will begin immediately after the data collection phases. Each code will be compared conceptually with others, and closely related concepts will be grouped into sub-themes, which will then be organized into main themes. This process will be carried out by three research team members, and any disagreements will be resolved through meetings with the study's scientific advisors. MAXQDA 10 will be used for data management during this phase.

3.2. Quality Assurance

All team members will be selected as outsiders to the research context, ensuring they have no prior contact with the participants or the research field. This aspect of the study context will be made clear to all team members. The researchers will strive to avoid any bias and preconceptions during data generation and analysis. The interdisciplinary research team, comprising eight Ph.D. researchers specializing in health policy and public health, will work collaboratively to maintain objectivity. The researcher responsible for data analysis will have no prior relationship with the study participants before conducting in-depth interviews. Our goal is to enhance the thoroughness and soundness of the research process and resulting interpretations.

Participants will be purposefully selected from diverse socioeconomic provinces of the country (patients) and various organizations (policymakers) to ensure a comprehensive range of opinions. Furthermore, to bolster the validity of the findings, codes and themes will be developed and reviewed by all members of the research team, and cross-validation of the findings will be conducted. By integrating different perspectives and data sources, we aim to establish a more comprehensive and reliable understanding of the phenomenon.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Expected Outcomes

The study is designed with the primary goal of assessing the impact of sanctions on the health status of the population and the healthcare system, transparently presenting the health situation using specific indicators and variables from 2000 to 2020 at national and sub-national levels in Iran. It is expected to yield the following outcomes:

- Identification of various sanctions against Iran and their history.

- Determination of the trend of changes in the studied indicators from 2000 to 2019 at national and sub-national levels.

- Identification of joint points in the trend of the studied indicators from 2000 to 2019 at the national level and by province.

- Determination of the relationship between health indicators and the imposition of sanctions.

- Identification of the attitudes and experiences of health professionals and policymakers regarding the impact of economic sanctions on public health and the healthcare system in Iran.

- Identification of the experiences and perceptions of the public and patients regarding the impact of sanctions on access to health services and the quality of treatment.