1. Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) anticipations, 20% of the total population will be over 60 years by 2050 (1). The need for long-term care (LTC) and dependence on others is expected to increase due to the increasing aging population and chronic conditions (2). Studies indicate that 1.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) is allocated to LTC by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and in 2050, it will double at least (3).

Long-term care consists of health services and social supports provided to older adults with chronic diseases and physical or mental disabilities to help them achieve and maintain optimal function and health levels (4). In response to demographic changes, growing long-term costs, personal preferences, and policies on encouraging aging in place, many countries have promoted formal home care (HC) while supporting informal caregivers and prioritizing providing care by relatives (5, 6). Deinstitutionalization has also been one of the goals of advanced countries to reduce costs. It is a term used to refer to the process by which institutional care is reduced and replaced by community- and family-based care arrangements or new small, home-based accommodations.

Home-based LTC includes services related to personal care and assistance with performing (instrumental) activities of daily living (ADL and IADL) and healthcare, such as nursing care (7). In Asian countries, except for Japan and South Korea, children, and family members have always been at the top of financial support and care (8). Home-based long-term care (HC) is a policy adopted by many countries for decades, such as China’s Star Light Project (9) and Sweden’s social services (10). These reforms respond to the changing family structures, women's labor force participation, and reduced caregiving capacity (11).

Long-term care policies vary widely among advanced industrialized economies, and each country has taken a different path to implementing reforms to be cost-efficient measures (12). One of these policies is introducing long-term care insurance (LTCI), which covers older adults in many countries (13). Other issues that emerged with the introduction of HC include governance changes, caregiver training, and supporting caregivers (14). Various studies have looked at the structure of HC systems in different countries and compared them (6, 12, 15, 16); however, there was no study that reports the information of all countries about this system.

2. Objectives

This scoping review aimed to explain the structure and how home-based LTC is organized in different countries.

3. Methods

This scoping review was conducted according to the five-stage framework developed by Arkesy and O’Malley (17). This study provides evidence to explain the structure and organization of home-based LTC in different countries. Therefore, the following questions were asked when examining the relevant literature:

• At what levels is governing done?

• Are there laws supporting HC for older individuals?

• How do older individuals qualify for HC?

• How are the benefits provided?

• How is financing done?

• Do formal or informal caregivers receive the training?

• How is the outcome of care evaluated?

• Are the care providers public or private/for-profit?

3.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

Four electronic databases (e.g., PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science) were searched for published articles in English from their inception in 2000 to 2023. The search began in January 2022, and the latest search was conducted in June 2023 by one of the researchers (FP). The review also included grey literature, such as preprint and peer-reviewed publications, guidelines, and guidance documents, in addition to documents, reports, and upstream policies published on the websites of reputable organizations, such as Google Scholar, Google, WHO, Health System Facts, OECD, and relevant ministries (Appendix 1 in the Supplementary File).

3.2. Selection of the Literature and Eligibility Criteria

This review included all published articles, reports, and documents in English on this topic. One of the researchers (KhM) performed a primary screening of published documents based on titles. In the second screening round of selected publications, the titles and abstracts were evaluated by two researchers (HM and KhM). In the final step, four researchers double-checked the full texts of the remaining articles for inclusion in the study (HM, KhM, HA, and AK). Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through consensus. Papers were excluded based on the following criteria:

• Lack of information about the structure and organization of HC

• Non-English language

• Content and documentation of invalid sources (e.g., websites, blogs, and online magazines that are not peer-reviewed and lack authors’ names and logos)

• Experimental studies

• Instrument developments

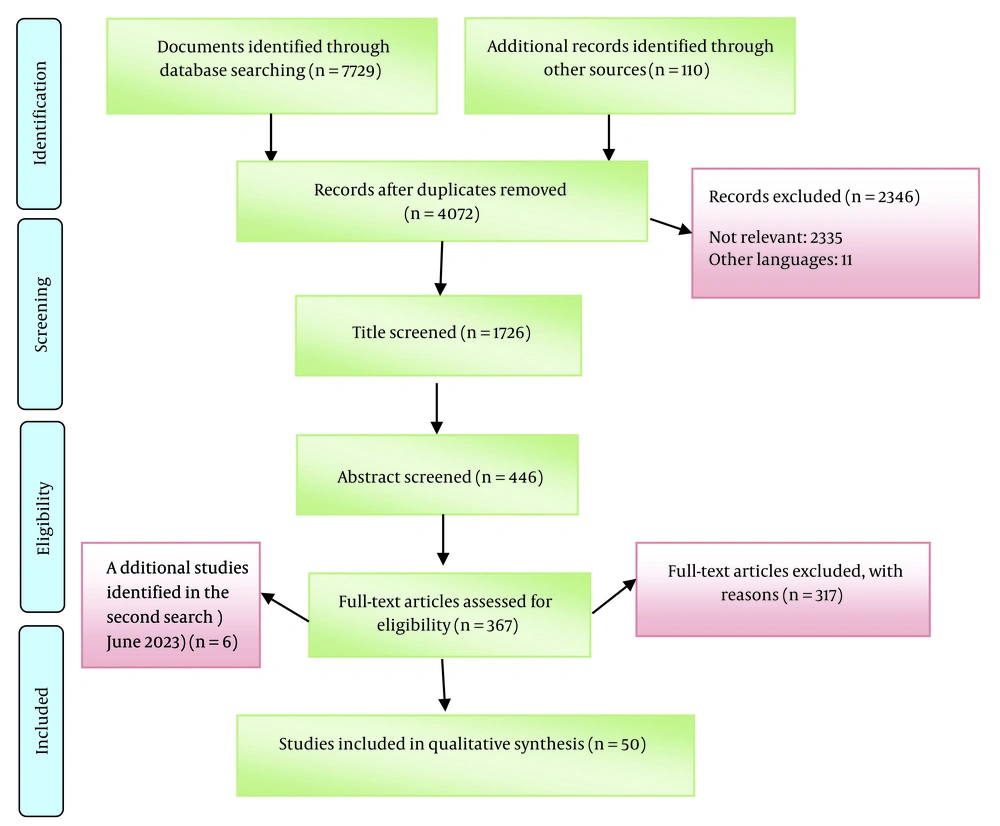

Endnote X8 software was used to screen and select articles and to identify and remove duplications. Figure 1 illustrates the process of screening and selection of documents.

3.3. Data Extraction and Charting

Following initial screening, two reviewers summarized and categorized the data in specific domains. The first author (KhM) developed an extraction form to capture study characteristics. The developed form was examined by four team members using 10 randomly selected studies. After finalizing the data extraction form, the extraction of study details was performed. This scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (18) (Appendix 2 in the Supplementary File). The final form included the information, namely first author (year), study objective(s), origin, design, purpose, and focused domain(s), related to the structure and organization of HC.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Studies

4.1.1. Countries Covered in the Papers

Based on Table 1, the publications included provided information on 23 countries. Most of the included studies on the structure of HC were performed in Germany (n = 13), Sweden (n = 9), and the Netherlands (n = 9). The HC system was not available in Asian countries except Japan and South Korea. Additional information is provided in Appendix 3 in the Supplementary File.

| No. | Author | Origin | Design | Purpose | Focused Domain(s) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Szebehely and Trydegard (19) | Sweden | Secondary data | The decline in HC and the marketization of services | 1, 2, 4 |

| 2 | Theobald (20) | Germany | Literature review | The interplay of formal and informal family care provision within the framework of LTCI and different types of formal care services | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| 3 | Ga (21) | South Korea | Document review | The LTC system in Korea | 2, 3 |

| 4 | Yakerson (22) | Ontario (Canada) | Perspective | The historical evolution of Ontario’s HC reform and the current challenges | 1, 2, 4 |

| 5 | Polivka and Luo (23) | United States | Literature review | The rationales for diminishing the role of the nonprofit Aging Networks | 1, 2, 4 |

| 6 | Mercille and O'Neill (24) | Ireland | Descriptive InterviewsDocument review | Patterns in private providers’ growth and their modes of operation in Ireland | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| 7 | Okma and Gusmano (25) | Japan | Commentary | Long-term care experience in Japan | 2, 3 |

| 8 | Lepore (26) | United States | Governmental report | An overview of LTSS, financing structure for LTSS, possible financing mechanisms, relevant policy, and policy recommendations | 1, 2, 7 |

| 9 | Sudo et al. (27) | Japan | Policy report | Financial aspects of the medical care and welfare services policy for older adults in Japan | 2 |

| 10 | Kodate and Timonen (14) | Asia and Europe | Literature review | How developments in formal HC bring different modes of increasing, encouraging, and necessitating family care inputs across welfare states | 2, 3, 4, 7 |

| 11 | Rostgaard and Timonen (28) | Europe | The final chapter of “Cultures of Care in Aging” Book | Key drivers of policy change and responses concerning the organization, financing, delivery, and regulation of HC in 11 European countries | 2, 3, 4 |

| 12 | Plaisier et al. (29) | Netherlands | Secondary data | Changes in community-based care use within 2004-2011 and changes in the explanatory effects of its determinants (i.e., health, personal, and facilitating factors) | 1, 2, 3 |

| 13 | Tur-Sinai et al. (30) | Europe | Cross-sectional | How the initial outbreak of the pandemic changed the supply of formal and informal care to older adults in European countries | 4 |

| 14 | Theobald et al. (10) | Germany, Japan, and Sweden | Comparative study | The effects of broader LTC policy developments on market-oriented reforms | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 15 | Wong and Leung (9) | China | Document review | Demographic shifts resulting in the emerging need for LTC in China and the issues facing LTC services | 1, 2, 5, 6 |

| 16 | Sigurdardottir et al. (31) | Iceland | Secondary data | The implementation of the Icelandic government’s policy on formal care of older adults in Iceland | 1, 2, 4 |

| 17 | Nadash et al. (32) | Germany | Literature review | The German LTC Insurance Program design and development | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 |

| 18 | Osterman (33) | United States | Governmental report | The circumstances facing paid home-care workers and a possible path forward | 4, 5 |

| 19 | Inaba (34) | Japan | Literature review | A brief overview of the situation of older adults and their caregivers in Japan | 1, 5 |

| 20 | Anttonen and Karsio (7) | Finland | Qualitative study | An overview of eldercare service redesign and deinstitutionalization of eldercare | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| 21 | Graham and Bilger (35) | Singapore | Document review | An overview of financing long-term services and support and ideas from Singapore | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 |

| 22 | Rhee et al. (36) | South Korea, Japan, and Germany | Comparative study | Developed LTCI systems and financing systems in three countries and lessons regarding revenue generation, benefits design, and eligibility | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| 23 | Alders (37) | Netherlands | Opinion paper | The innovation in HC by Buurtzorg, the reforms concerning community nursing in the Netherlands, and their possible impacts on caring for frail older adults | 2, 3, 6 |

| 24 | Chon (38) | South Korea | Literature review | The LTC infrastructure in Korea, market-friendly policies used to expand the infrastructure, and positive results of the expansion of the LTC infrastructure and the emerged challenges | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| 25 | Beck et al. (39) | Poland | Document review | An overview of framework, problems, and prospects of long-term HC in Poland | 1, 2, 7 |

| 26 | Asiskovitch (40) | Israel | Document review | The structure of LTCI, its sources of financing and scope of expenditure, trends among the beneficiaries and the generosity of the program, and its implications for the solidarity of Israeli society with its aged population | 2, 3 |

| 27 | Kroger and Leinonen (41) | Finland | Document review | The trends and changes in HC services for older individuals during the last two decades in Finland | 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 |

| 28 | Glendinning (42) | England | Literature review | Tracing the development of HC services in England since the early 1990s | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 |

| 29 | Radvanský and Páleník (43) | Slovakia | Governmental report | An overview of the Slovakian LTC system | 1, 2, 3 |

| 30 | Saltman et al. (12) | Singapore and Sweden | Comparative study | The framework of financial risk-sharing and the configuration and management of health service providers in Singapore and Sweden | 2, 3 |

| 31 | Mahoney (44) | United States | Commentary | Information on how states have responded using the new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) toolkit during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic | 4 |

| 32 | Osterle and Bauer (45) | Austria | Literature and document review | The development of the HC sector in Austria and the impacts of the traditional family orientation to care | 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 33 | Casanova et al. (46) | Italy | Rapid literature review Expert interviews | Impact of Occupational Welfare (OW) schemes on the different actors involved in HC provision | 1, 3, 4, 7 |

| 34 | Frericks et al. (47) | Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark | Comparative study | The way welfare states institutionally frame the working conditions and social security for family caregivers and analysis of the social risks related to this framework in three countries | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7 |

| 35 | Mavromaras et al. (48) | Australia | Cross-sectional | Information on the residential facilities, HC, and home support outlets as employers and businesses, the presence, causes, and consequences of skill shortages, job vacancies, and the composition of the workforce | 5 |

| 36 | Palesy et al. (49) | Australia | Integrative review | Home care recipients and their needs, funding, and regulation, care worker skills, tasks, demographics, employment conditions, and training needs | 1, 4, 5 |

| 37 | Van Eenoo et al. (15) | Europe | Literature review | Comparing community care delivery with care-dependent older individuals in Europe | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| 38 | Genet et al. (6) | Europe | Systematic review | Home Care in Europe | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| 39 | Kiersey and Coleman (16) | Europe | Scoping review | Approaches to the regulation and financing of formal HC services in four countries | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| 40 | Riedel (50) | Europe | Short overview | Providing an overview of the availability of cash benefits that can be used to finance informal care in 21 Member States of the European Union and was written during the ANCIEN (Assessing Needs of Care in European Nations) project | 2, 3 |

| 41 | Rodrigues and Glendinning (51) | England | Qualitative study | Recent changes in markets for home (domiciliary) care services in England | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| 42 | Caughey et al. (52) | 11 countries | Governmental report | Quality assurance of care in 11 countries | 7 |

| 43 | Owen et al. (53) | United States | Literature review | How HC is provided, the cost associated with each type of service provision, how to identify resources for service provision and the indirect costs associated with family members providing HC | 2, 3, 5 |

| 44 | Gori (54) | Italy | Literature review | How has the provision of publicly funded HC changed over the last decade, and why is the result different from that expected? | 1, 2, 3 |

| 45 | Ghasemyani et al. (55) | Iran and selected countries | Comparative study | Comparison of LTC components for the elderly in Iran and selected countries | 2, 3 |

| 46 | Miyazaki (56) | Italy and Japan | Comparative study | Identifying the state-family relationship in the provision of LTC for older adults in Italy and Japan | 3 |

| 47 | Lee et al. (57) | OECD countries | Policy analysis | Investigating the characteristics of LTC financing in OECD countries | 1, 2, 3 |

| 48 | Zhou and Zhang (58) | Japan | Literature review | Description of LTC in Japan | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| 49 | United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) 2022 (59) | Asia | Governmental report | Asia Pacific Report on Population Aging 2022, Trends, Policies, and Good Practices on Older Individuals and Population Aging | 1, 6 |

| 50 | Rostgaard (60) | Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden | Comparative study | Changes in institutional features of national LTC systems and the implication for equality | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 |

Characteristics of Included Studies

4.1.2. Design of Studies

Most of the included studies were literature reviews (6, 14-16, 20, 23, 32, 34, 38, 42, 45, 46, 49, 50, 53, 54), and 3 of them had scoping (16), systematic (6), and integrative (28) designs and used peer review studies to explain HC in the target countries. Eight studies (9, 21, 24, 35, 39-41, 59) were also document reviews, meaning that they gathered information and data from reputable organizations, such as the WHO, the Insurance Organization, or the Ministry of Health (MOH), and such organizations. Seven studies (10, 12, 36, 47, 55, 56, 60) have investigated the HC system or its domains in several countries as a comparative study. In addition, 5 valid governmental reports (26, 33, 43, 52) that contained valuable information and could help enrich the information were included in this study.

4.2. Main Domains of the HC Structure in Countries

The obtained information was classified into 7 domains, including governing; LTCI, eligibility and financing; benefits; marketization and free choice system; workforce training; quality assurance of care; and supporting caregivers. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies included in this study. The main domains of the HC structure in countries are pointed out and explained below (Table 2).

| Country | Governing | Eligibility | Benefits | Financing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | Central Government and Ministries: Determining the Legal Framework; Municipalities: How to provide the service, type of strategies and principles of providing home care services, and how to finance | Needs-tested; Means-tested | Cash (mainly) and in-kind | Public and private health insurance and co-payment |

| Sweden | Similar to France | It is needs-tested; however, there are no strict guidelines at the national level regarding the eligibility criteria. | Combination of cash and in-kind | 68%: Local taxes; 18%: Government subsidies and grants; 5 - 6%: Co-payments |

| Japan | Similar to France | Needs-tested | In-kind | Compulsory public health insurance, LTCI, and taxes (25% national, 12.5% provincial, and 12.5% municipal); Government subsidies, co-payment, and out-of-pocket (50%) |

| South Korea | Similar to France | Needs-tested | In-kind (mainly) and cash (very limited) | A tax-based system, social insurance, and LTCI |

| Italy | The central government directs public tax revenues for publicly financed healthcare, defines the benefit package, and provides overall supervision. Each region is responsible for organizing and providing health services through local health units and through accredited public and private hospitals. | Means-tested Availability of informal caregivers | Cash and in-kind | Taxes, health insurance, and co-payments |

| Netherlands | Similar to France | Needs-tested; Means-tested; Availability of informal caregivers | Cash and in-kind | Compulsory public insurance, national or municipal taxes, and co-payment |

| Singapore | Long-term care policymaking and financing are done by the Ministry of Finance (MOF), Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF). Statutory bodies determine eligibility and payment of subsidies. | Means-tested | Emphasis on cash benefits based on income (means testing) to encourage family caregivers to provide in-kind care | Out-of-pocket (40%), private LTCI (ElderShield) (9%), charitable donations (9%), government subsidies to LTSS providers (16%), and means-tested government subsidies (26%) |

| Canada | Each province is left to decide and design how and to what extent it will provide home care services and how it will pay for them. | Means-tested | Insurance and tax | |

| Germany | In Germany, at the Länder level, states oversee the regulation of LTC and might also finance investments in HC agencies. | Needs-tested | Combination of cash and In-kind | Compulsory social insurance and co-payment |

| Finland | Similar to France | Needs-tested; Means-tested; Availability of informal caregivers | Cash | Municipal taxes, subsidized by the state, and co-payment |

| Ireland | There are guidelines at the national level, and municipalities act independently in providing services. | Needs-tested | Cash | National or municipal taxes (97%) and private out of pocket |

| United Kingdom | National government guidelines indicate the general principles that should be followed. Local government is responsible for assessment and care management. | Means-tested | In-kind and cash | General taxation (mainly), local taxation, and co-payment |

| Denmark | The Danish municipalities (local authorities) are obliged to offer help and care to dependent older individuals. | Needs-tested; Means-tested; Availability of informal caregivers | Cash or in-kind | National or municipal taxes and co-payment |

| Austria | National and provincial legislation, administration, and funding | Needs-tested | Cash (mainly) and in-kind | Social insurance, general taxation (largely), and co-payment |

| United States | Eligibility, benefits, and even sources of funding for programs differ between states. | Means-tested | Most states have in-home assistance programs for low-income seniors who are not eligible for Medicaid. Some of these programs provide cash assistance; others provide care services and respite. | Medicaid, Medicare, LTCI- general taxation, and co-payment |

| Iceland | The Minister of Health and Social Security is responsible by law for matters concerning the aged, and the Ministry is responsible for implementing international obligations in the field. The Ministry of Welfare of Iceland is responsible for formulating policies and guidelines, and Health services are provided by the state; however, the local government is responsible for social services. | Needs-tested | Cash | Social insurance, national or municipal taxes, and co-payment |

| Poland | In addition to the sectoral divisions, resources are distributed among national, provincial, and local authorities, each executing its finances by administering its own programs. | Needs-tested (score below 40 on Barthel scale) | 56%: In-kind; 44%: Cash | Low level of public spending and significant co-payment on formal care services |

| Switzerland | Responsibilities for LTC lie with sub-national authorities. Municipalities and, to a lesser extent, cantons are responsible for assessment and aged care. | Needs-tested | Cash and in-kind | Compulsory public insurance, significant co-payment, the old-age and invalidity benefit system (AVS-AI) |

Components of Home Care in Different Countries

4.2.1. First Domain: Governing

Regulation in geriatric care has led authorities to prioritize the care of seniors and universal care and allocate benefits for community-oriented care and quality of care (QoC). Legislation related to HC in Sweden includes Social Services Act 2001 (SSA), the Local Government Act 1991, and the Public Procurement Act 1992 in Sweden (10, 16, 30).

Japan approved the Welfare of the Elderly Law 1963 and the Aged Society Basic Law 1995 related to work, pension, LTC, and family care leave (10, 34). The importance of aging in place is emphasized in some countries, such as Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, Iceland, Finland, Germany, and Belgium (except Italy), which is accompanied by an increase in informal family caregiving in some countries, such as Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland (15, 60). The Starlight Project in China (9) and the Community Care Project in South Korea (21) are aimed at promoting this goal.

In the governing field, there have been reforms with the aim of decentralization. Moreover, in most countries, including Finland (7, 41), Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Scotland, France (15, 16, 29), and Japan (36), central government and ministries set the legal framework, and municipalities are autonomous in the way of offering, kind of strategies, and the principles of providing HC services and financing.

In the United States, more recently, health maintenance organizations (HMOs) have entered the caregiving arena, operating managed LTC (MLTC) programs, reducing the role of non-profit Aging Networks (AN) that have been responsible for HC programs for the past 40 years (23). In Nordic countries, there is no uniform welfare state; however, welfare municipalities differ significantly from each other in the level of services and the quality of services (60). Home help services are provided by the Health Service Executive (HSE) and non-profit organizations; nevertheless, HC packages are in the hands of the HSE and private companies in Ireland (16, 24). Since 1993, local authorities in England have been responsible for assessing needs, funding, allocating the overall budget, and ensuring the provision of HC services (42, 51). In Belgium and the Netherlands, nursing care is a federal responsibility; nonetheless, domestic care is mainly a social responsibility (15, 16, 29).

4.2.2. Second Domain: Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI), Eligibility, and Financing

Financing systems for LTC in OECD countries can be classified into tax-based, social insurance, and private insurance-based models, and mixed models are common, in which social insurance is divided into two categories: health insurance-based and LTCI-based (57). In Germany, needs assessment (NA) and quality assurance are the responsibility of the Medical Board of Health Insurances (MDK) (16, 47). After the providers’ registration in the region’s LTCI funds, the contract is concluded between the provider and insurance fund regarding the prices and quality standards (20, 32).

The main financing system in Austria is tax-based (57). A stricter focus than publicly funded provision is on the Austrian older person with broader care needs (16, 45). Austria (and Germany) is described as a private and facilitated public care model with a family orientation strategy (45).

South Korea became the second Asian country after Japan to introduce mandatory social LTCI (38). Eligibility decision is made based on six levels of needs managed by each local LTCI company (21, 36, 38).

In the United States, Policy H-280.991 addresses financing of LTC and tax incentives, employer-based LTC coverage, tax deduction or credit for family caregivers, and QoC (26). Medicaid is the primary payer for publicly funded LTC, covers individuals below the poverty line, and is funded by the federal and state governments (53). Medicare pays for LTC only for individuals who typically need skilled services or rehabilitative care after being hospitalized (23, 26). Most seniors enroll in Medicare with a supplemental insurance policy (Medigap) or a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan that provides additional benefits to the client (26).

The public health insurance coverage system in Japan was launched in 1961 and is available with mandatory affiliation, easy access, and low co-payments (27). According to the Gold Plan 1989, universal tax-based home services were delivered to older adults at the municipal level, and then universal LTCI without means-testing was introduced in 2000 due to individuals’ protests against the tax increase (10, 14, 36). After reaching the high-cost LTC service limit, beneficiaries pay 100% of their LTC costs out of pocket (36). However, the share of co-payment has increased to 20% since 2015, and the financial responsibility of families has not been eliminated (10, 58).

In Southern Europe (Portugal and Spain) and Western Europe (England, Ireland, France, Australia, and Canada), the financing system is based on taxes. However, in Estonia, Hungary, Belgium, Switzerland, and Poland, the health insurance system is used as the main source of financing (57). Eligibility is based on means testing in Belgium, Romania, and Spain (50). Home care in Slovakia is provided for the person based on income (means-tested) and level of the person’s need. Eligibility is assessed based on strict guidelines by an advisory committee consisting of physicians and social workers, and services are provided according to the patient’s needs in one of four areas, namely self-service, household activities, basic social activities, and supervision (43).

In the Scandinavian countries, the allocation of HC benefits (except domestic assistance to a certain extent) is universal and more comprehensive (12). In Sweden, nurses perform NA for nursing care (6, 37), and financing is mainly through local taxes (12). Complementary cash and in-kind benefits are available after the NA (16). The dominant fiscal responsibility is vested in public sector tax funds, and a combination of elected and administratively appointed public sector officials makes decisions about the expenditure of those funds. The national government allocates more funds for social services (12).

In Scotland (16) and Slovakia (43), national or municipal taxes are a source of financing. Co-payment is another source of financing in all countries, Netherlands, France, Iceland, Ireland, Finland, Germany, England, Slovakia, Denmark, Germany, Belgium, and Italy (6, 15). Fee-charging and subsidized multiservice by the Ministry of Civil (MCA) of China are available for three categories of people: those who have no family support, those who have low income, or those who have disabilities (9).

Independent assessment agencies do NAs for service receipt in the Netherlands (6). The Center for Indication of Care (CIZ) and its regional branches are responsible for NA and eligibility and provide cash and in-kind services (16).

The healthcare financing system of Singapore is based on individual health savings accounts (Medisave), mandatory health insurance (MediShield Life), and health insurance for low-income individuals (MediFund) (35). The Singapore government proposed replacing the voluntary MediShield in 2020 with a comprehensive and mandatory LTC coverage program called CareShield Life, which all citizens over 21 must hold and pay (12, 35). MediFund is a fully government-funded safety net for low-income individuals who do not have sufficient medical savings account balances to pay for necessary services (35).

In Iran, due to the limited access to LTC and the lack of a comprehensive LTC system for older adults, no criterion has been defined to determine the eligible elderly. In a limited way, there are non-cash benefits for the elderly from the welfare organization to provide rehabilitation and medical equipment for older adults (55).

4.2.3. Third Domain: Benefits

Benefits are usually provided to seniors in two forms, namely cash and in-kind benefits. In-kind benefits are care services that a person receives. In some countries, such as Japan (56) and South Korea (38), the focus is on providing this type of service. However, cash benefits are usually deposited in the person’s account as money that can be used to purchase services from a formal caregiver or family (61).

Personal budgets (PBs) are paid to older adults in the England LTC system and used to purchase services and tasks through HC by the care manager (6, 42). Personal budgets mean public resources allocated to eligible adults to finance residential or community-based support, which can be held as a direct cash payment in a designated bank account or used to hire a personal assistant or relatives, purchase HC, or be used to purchase services, such as taxis or ready meals. However, 80% of older individuals leave their budget to the local authority to fund their HC services (51).

In Norway and Finland, where the use of care allowances for informal care is increasingly common, families are expected to participate extensively in caring for older relatives at home (60). In southern Europe, receiving care from informal caregivers is more common (6), and families use the cash allowance received to hire migrants (common in Italy) or family caregivers (24).

In addition to cash-for-care, fiscalization (tax allowances) is also allocated to the Irish service recipients (6, 24). Finnish seniors also benefit from service vouchers, tax rebate systems, personal budgets, and care allowances for pensioners (6, 7).

In Singapore, the means-tested cash benefit scheme called the Silver Support scheme was proposed as a safety net and was approved in 2015. The aim was to encourage family caregiving (14).

In Germany, based on five care levels, older individuals are free to choose cash or in-kind benefits, inpatient care, and a combination of both, and ancillary services, such as respite, home modifications, counseling, and pension contributions (10, 16, 32). Ethnic minorities and individuals with low economic status usually choose family care payments. On the contrary, individuals with higher welfare status prefer to use cash for care to buy care from formal caregivers (14).

The Community Care (Direct Payments) (Scotland) Regulations 2003, as amended in 2005, is related to direct payments for HC services (16). In Italy, individuals receive companion allowance and spend it on migrant caregivers, which is outside of formal care regulation, where the role of family caregivers is highlighted, and paid caregivers (14, 46). In France, the supervision of cash grants is stricter, and in Italy, it is more liberal (28).

According to the Family, Nursing, and Parental Benefits Act, the state budget grant nursing care allowances are a fixed amount of income not linked to the beneficiary’s income level in Poland (39). Financial aid is concentrated on individuals with poor social and economic status, and low-income individuals’ needs are often unmet (50).

4.2.4. Fourth Domain: Marketization and Free Choice System

In many countries, a competitive care market with a free user choice system was created to reduce public costs. With the marketization of the HC system, policies in many countries are aimed at allowing clients to freely choose between different types of service providers to receive quality care (6).

Nowadays, in many developed countries, HC follows neoliberalism, market orientation, and privatization that aim for decentralization or transfer of central government power to local and regional levels with the aim of reducing costs and quality improvement (22). In Greece, informal care is still dominant in the HC sector. Private HC providers have emerged to meet some of the out-of-pocket needs (24). In the Scandinavian countries (except Norway), Germany, France, South Korea, Israel, Australia, Portugal, and England, private and profit providers have grown significantly (14, 24, 36, 40, 49). During the entry of for-profit companies into the United States HC system, corporate control has gradually expanded to all areas of healthcare and now extends to publicly sponsored LTC through contracting out of Medicaid LTC programs in several states (23).

According to Act on the Affairs of the Elderly, no. 125/1999 in Iceland, open geriatric services include home healthcare provided by a designated health district center (run by the national government) and cover assistance with ADLs and nursing care. Furthermore, social assistance at home includes some services, such as assistance with household chores (IADL) and Meals on Wheels provided by local authorities, municipalities, and for-profit companies (31).

The private sector providing services has increased, and according to Act on Free Choice Systems, individuals are autonomous in choosing the service provider in Sweden (10, 19), Finland (7, 47), Germany (10), and Japan (10). At the beginning of the 1990s, two new laws (i.e., the Local Government Act 1991 and the Public Procurement Act 1992) enabled Japanese municipalities to award publicly funded care services to profit and non-profit providers based on competition. Local levels have full authority to implement market-oriented reforms announced by national levels (10).

Although marketization increases QoC, some challenge comes with the emergence of the gray market, where families employ immigrants without valid certificates for care to reduce costs (5, 20, 24, 35, 46, 47). High-income are likely to pay higher co-payments or out-of-pocket to use private caregivers to meet their needs, and they will benefit from high-quality care by purchasing services privately; nevertheless, low-income individuals will not benefit from this (29).

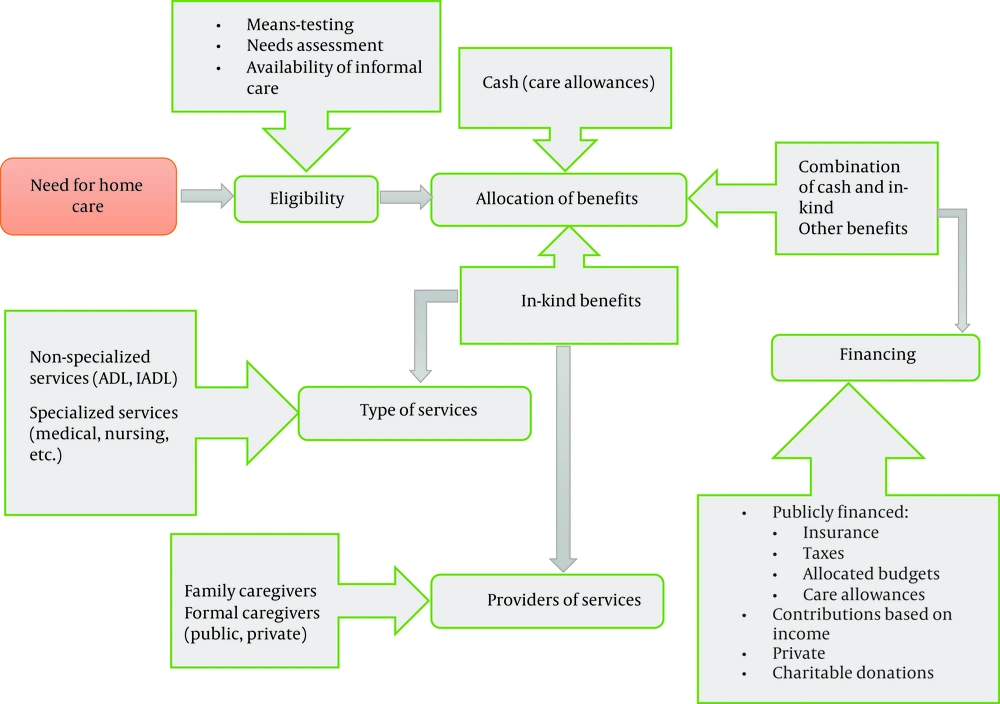

One of the major crises that caused the shift in HC arrangements is the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In the Netherlands, Poland, Germany, and Switzerland, the response of informal care networks has been one of the most potent responses to support the seniors in the first wave of the epidemic and, at the same time, providing services at home has continued with the minor problems (30). Many states in the United States, encouraged by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), are moving toward self-directed home and community-based services (HCBS), in which participants are free to hire and manage workers. Hiring families as caregivers who have recently become unemployed due to the pandemic situation, limiting the entry and exit of individuals to seniors’ homes, flexibility of choice between self-direction and provided services by agencies, and increasing the budgets allocated to self-government are the reasons for the usefulness of this approach in the COVID-19 pandemic (44). The present review developed a model to show the structure of home-based LTC services in Figure 2.

4.2.5. Fifth Domain: Workforce Training

In different countries, there are different educational levels to qualify caregivers, some of which are mentioned. Some countries have not considered a requirement for this issue. In Japan and Sweden, where HC includes family-related services, the level of competence is lower (10, 16). Some evidence state that in Germany, body care requires 2 to 3 years of professional training, and HC requires a few months to a year of training (16, 20). Unlike in Italy, in Taiwan, it is mandatory to certify the qualifications of migrant caregivers (14). Danish municipalities are autonomous regarding caregiver training (47). Portugal, England, Poland (6), Netherlands (16), Scotland (48), and Austria (45) consider the training of caregivers mandatory.

Most of the healthcare workers (HCWs) are women within the age group of 45-54 years. Mental health disorders, dementia, and person-centered planning and care are reported as the three most common training priorities for HCWs (49). After the issuance of professional standards for the care of older adults by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security of China in 2002, the recruitment and training of care workers were given more priority (9). In the United States, HC teams include companion/sitter, certified nurse’s aide (CNA)/personal care aide (PCA), and/or licensed practical nurse (LPN)/registered nurse (RN) (53). A sitter generally has a non-medical role in an individual’s life. Home health aides are either CNAs or PCAs, and their roles are very similar. Usually, a PCA is not required to be certified. A PCA helps with feeding, hygiene, and mobility (33). In most states, a high school diploma and completion of a 75-hour training program are required to become a CNA. An LPN works under the supervision of an RN or physician (53). Since 2010, Korean care workers have received a care certificate after passing a formal exam. A Level One certificate is awarded to personal care workers who have completed 240 hours of theory and field training, and a Level Two certificate is awarded upon completing 120 hours of training (36, 38).

4.2.6. Sixth Domain: Quality Assurance of Care

One of the other components that most countries emphasize is guaranteeing HC quality. Even in some countries, there are protocols and legislation on this issue. For example, in Germany, Quality Assurance and Consumer Protection law in 2002 addressed this issue (20).

Case managers in Iceland, Sweden, Italy, and Finland and integrated care trusts in England were used to integrate and increase the quality of HC services (6). Accreditation standards are set nationally, and ISO 9001 is the most common quality management system (QMS) used by German HC services (16). Singapore MOH is responsible for monitoring the quality of services based on national standards that ensure the safety and dignity of clients and meaningful client-centered care by trained staff (35). South Korea has limited monitoring for continuous quality improvement (36). The quality of life in the Netherlands is measured by a Consumer Quality Index (CQ index), which asks service consumers about their experiences with QoC (37).

In England, all organizations providing HC must register with the Care Quality Commission, and regular inspections of providers are carried out (42). The National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW) of Sweden monitors the quality and safety of care services (16). In Canada and New Zealand, the quality of HC indicators with different domains is compiled using the Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessment. The Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set is used as a screening and assessment tool for the health status of home and facility residents in some countries, such as Finland, Iceland, and the United States (52). Five indicators are collected by the Public Sector Residential Aged Care Services (PSRACS) of Victoria, Australia, and are reported to the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services quarterly (52). The quality indicators of LTC of Denmark are based on annual municipal or other administrative data from registries or from a bi-annual survey of older individuals. Five questions about safety, effectiveness, respect, responsiveness to individuals’ needs, and good management are assessed for all care providers in the United Kingdom (52). In Italy, there is no mechanism to monitor and guarantee QoC at home (54).

4.2.7. Seventh Domain: Supporting Caregivers

In some countries, governments support informal caregivers to maintain the family care system, as mentioned in the articles below.

In Germany, services include training, payment of pension, respite breaks, health insurance, unemployment insurance, and interest-free loan leave for family caregivers (14, 32, 36). Moreover, in Finland, some facilities, such as loans and leave, for family caregivers have been considered (41). In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark, family members who care for parents are entitled to working leave, care vacation, unemployment insurance, respite care, and pension (6, 15, 47). Stability Law 2016 in Italy is related to granting benefits to employees to support them and includes tax incentives for companies supporting employees, adopting the voucher system to access services, and granting benefits to low-income employees (46). According to Act No. 447/2008 on financial allowances, a Slovakian informal caregiver who provides intensive care can use social contribution (cash benefits or similar) (43). Additional care leaves, cash benefits to support HC, vouchers to buy care services, and the direct provision of care by service providers are benefits in the framework of Occupational Welfare (OW). Occupational Welfare refers to employee benefits and services provided by employers and unions based on employment contracts and generally supports family care (46).

In Australia, the Aged Care Support Program sets out several guiding principles to enhance QoC. This program provides support, education, and information to seniors receiving senior care services. To ensure sufficient and qualified caregivers in Singapore, the MOH and the Integrated Care Agency assist providers in recruitment and salary increases through special schemes. Training and capacity-building assistance are also available to meet the needs of healthcare professionals. The Chinese government offers training courses for caregivers and nurses focusing on geriatric care at home (59).

5. Discussion

The present study showed how the HC system is organized in different countries. The present review categorized the extracted information from 50 studies into seven domains. Comprehensive information related to these 10 areas was only available for some countries. Information on Asian countries (except South Korea, Japan, and Singapore) and Central and Eastern Europe was scarce.

The common domains between countries are legislation, marketization, precise governance levels, quality monitoring, caregiver training, decentralization, and autonomy in HC organization for local authorities and municipalities. Eligibility criteria for receiving care were common in some countries and varied in others. For example, in England and the United States, a person is qualified based on his/her level of need and wealth; however, in Sweden and South Korea, a person’s need is the criterion for receiving care regardless of wealth. Some countries also do not have clear eligibility criteria for this issue. Others have differences in eligibility criteria.

The current study’s findings showed that most countries focus on older individuals with the highest level of need and do not have equal access to services for those with low and moderate needs. Home-based care and prioritizing preventive and rehabilitation policies for all older adults at different levels of need can bring fairness (62). Furthermore, well-designed health promotion and self-management programs focused on self-help can reduce healthcare utilization and related costs (27). In Iran, existing health services are required to meet the needs of older individuals (63, 64). One of the services that can be provided at home is the spiritual health of older adults, which in the context of Iran, religion is considered very important and can affect the results of care (65). Using the successful experiences of countries can also be a light for formulating appropriate policies. For instance, in the Netherlands, Buurtzorg (Dutch for neighborhood care) is a non-profit HC company known for self-management, intra- and inter-departmental cooperation, maximum consumer satisfaction, and greater productivity. After the 2015 reforms, care is more patient-centered (37).

Concerns have been raised about the financial sustainability of LTCI due to the growing demand and costs of geriatric care (66, 67). In many developing countries, sustainable funding mechanisms do not exist (68). Long-term care financing should be based on a reliable and predictable source (69). In addition, accurate assessment for eligibility can improve financial sustainability (66).

The lack of strict quality monitoring causes a decrease in individuals’ satisfaction and an increase in hospitalization rates (70), and the results of the present study also showed the lack of a clear standard of quality assessment in some countries. Requiring the supervision of QoC based on strict standards and indicators can smooth this challenge (62).

The decline of informal care, the rise of women’s labor force participation, and the marketization of HC systems have reduced family care capacity and worsened HC workers’ conditions, especially for women and minorities (22, 47, 71). This issue of the provision of care allowances that employ family members, primarily daughters, has been protested by feminist groups (22).

In many European countries, cash payments support family-based care; however, more than public support is needed, and individuals must purchase part of the services privately (10). Conversely, in Asia, except in Japan, children and family members have always been principal caregivers and financial providers (14). Creating policy reforms to support formal and informal caregivers, creating suitable working conditions, establishing fair wages and benefits (e.g., work leave and respite care), maintaining their dignity, reviewing the role of HCWs and finding ways to create more productivity, expanding the scope of activities of HC aides, allowing easier entry of large non-profit providers into the market, a strict inspection of employee training organizations, developing and enforcing adequate guidelines to protect personal care workers, and formal and clear division between care and nursing in both theory and practice are the political solutions (33, 39).

5.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study and Further Research

This study had a comprehensive overview of different HC systems of different dimensions. Compared to previous review studies, this study is more comprehensive, newer, and geographically broader (6, 15, 16). In addition to providing valuable experiences of different countries, this study also had limitations. It also had limitations, such as excluding non-English studies, not accessing some web-based information, and not searching for “COVID-19”. It is recommended to study the details of different dimensions in several review studies focusing more on gray literature. The educational contents of formal and informal caregivers, benefits and challenges of marketization, HC reforms and innovations in the COVID-19 pandemic, quality indicators, and successful innovations of countries to sustain LTC financing should be explained more widely.

5.2. Conclusions

This review can generate novel insights into designing HC systems according to different contexts. Comprehensive information on HC organizations for older adults was only available in some countries. Therefore, further in-depth studies are needed to assess each component of the HC system separately. Defining legal rights and responsibilities for caregivers and older individuals, universal coverage of LTCI for all older adults, financial and care options to help pay for HC, and training family caregivers are recommended for developing countries.