1. Context

In recent decades, the tobacco epidemic has spread across the world. Several complex factors with cross-border effects, such as trade liberalization, global marketing, direct foreign investment, transnational tobacco promotion, advertising and sponsorship, and the international movement for contraband and counterfeit cigarettes, have facilitated its spread (1-3). The globalization of the tobacco epidemic has had devastating effects. Over 8 million people died from tobacco-related diseases in 2019. Tobacco has caused more than half a trillion dollars of economic damage (4, 5). Moreover, based on reports of the World Health Organization (WHO), tobacco use, as the most preventable cause of death, disability, and economic pasting, is a global public health challenge (3, 6, 7).

At the global level, the first profound policy to control the tobacco epidemic was the World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), adopted in 2003. The FCTC has identified three main types of obligations: Those aimed at reducing the demand for tobacco products, those focusing on decreasing the supply of tobacco products, and those aimed at reducing exposure to second-hand smoke (8). Framework Convention on Tobacco Control provides a global policy framework for addressing tobacco issues at the local level. Member states of the Convention must consider how the provisions will be implemented in their countries. However, FCTC obligations are difficult to enforce because there is no powerful international entity to hold states responsible for the obligations they accepted under the Convention or to apply sanctions if they are not met. For example, while 180 countries enacted some protocols to limit exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, these protocols vary widely. Many countries still need comprehensive legislation on creating smoke-free indoor public places (8).

Political, economic, and societal factors can influence the context of a policy (9). To understand how a policy has been developed and implemented, it is important to investigate how various actors interacted and how it changed the implementation process. Moreover, the contextual opportunities and constraints to policy change and formal and informal practices through which choices are made over the life course of a policy in specific areas must also be considered. The players affected by the reforms, the power of stakeholders, their basic interests and situations, and the level of obligation towards the reform play important roles in policy implementation (10).

Until now, implementing public health policies to prevent the global, regional, and national tobacco epidemic has gone through a difficult and long path. More than half of the Member States of the FCTC reported substantial constraints and barriers preventing them from completely implementing the Convention (11). The history of tobacco control is characterized by evolving medical research, public health advocates, the tobacco industry, governments, mass media, and the perception of societies toward smoking behaviors. Little is known about the difficulties of balancing interest groups to implement tobacco control policies properly. Without the knowledge of the main actors and their interests, there would be a gap between what has been decided and what is implemented. This paper aims to explain how India and the United Kingdom, two countries with different political, social, and cultural contexts, implemented FCTC.

2. Evidence Acquisition

A comparative study was done for tobacco control in UK and India in 2022. This qualitative study reviewed literature, observational data, and legal documents about tobacco use to identify and explain the factors that pose challenges to implementing tobacco control policies. Steps taken to carry out this narrative review included:

(1) Identifying keywords through a simple search in Google Scholar papers.

(2) Looking for relevant documents in online databases such as MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science and governmental and international organizations’ webpages such as WHO and health institutions and searching for keywords including tobacco, smoking, tobacco control, cigarette, FCTC, cigarette industry stakeholder, interest group, policy, and UK and India from 2000 to 2020.

(3) Reading the titles, abstracts, and full texts of searched papers and removing irrelevant and duplicate ones.

(4) Reviewing the remaining papers.

(5) Summarizing the findings and integrating them into the writing.

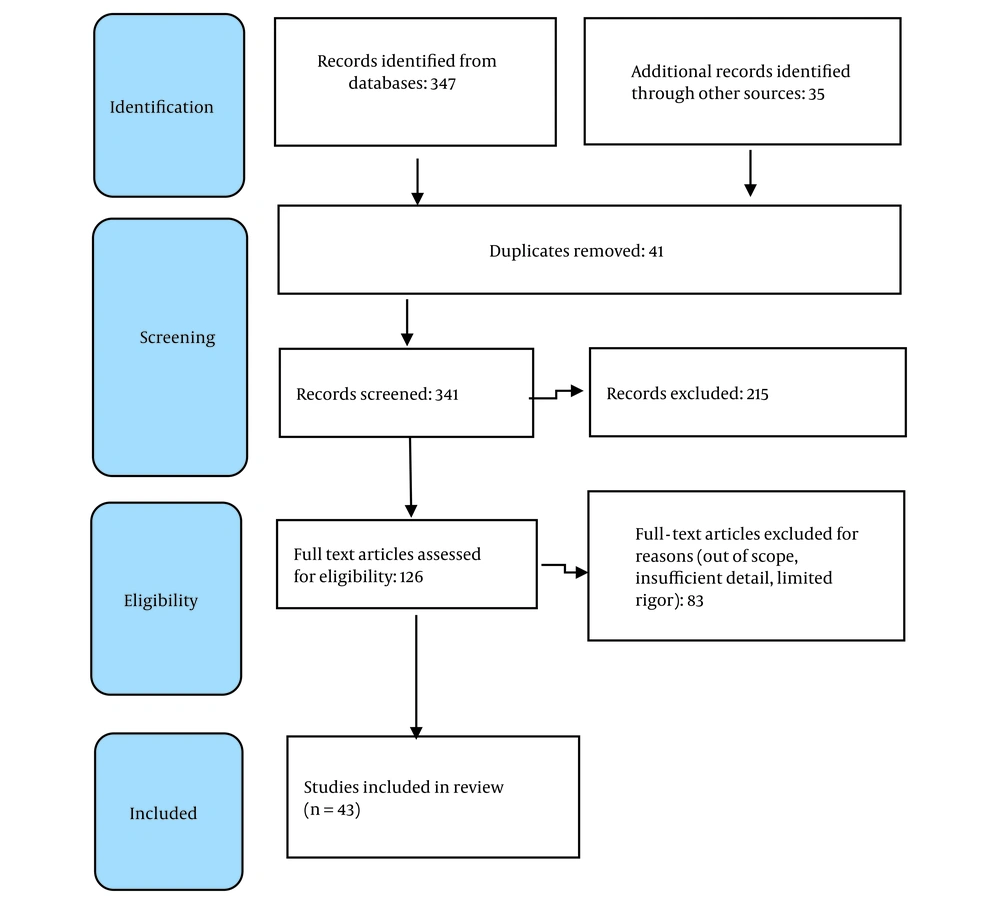

The papers were subjected to systematic retrieval, storage, and quality assessment. For coding, extraction, and data analysis, thematic analysis was used—the thematic analysis of the data involved reading through the extracted text and identifying the key messages. The inclusion criteria were whether the papers discussed the UK and India’s tobacco control policies and actions and related institutional changes as well as the situation of stakeholders. Moreover, the papers published by reliable scientific journals and reports published by WHO and health authorities that have been cited by other scholars and contributed to the understanding of the subject were included. To assure the quality of included papers, the WHO and health system reports were prioritized in any contrast found in the selected papers. Considering the purpose of the study, the papers discussing the health effects of smoking and related health services were not included. Exclusion criteria were the lack of online full text, articles about theory rather than actual practice, and articles not in English. A summary of the review process is presented in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

The situation of the main role players, namely the government, medical doctors, the tobacco industry, and civil advocates, were followed to compare the two countries. The historical changes in the government’s policies were reviewed over time. For analysis, the data collected were summarized and compared. The policies of the governments, similarities and differences, barriers, and facilitators were extracted and listed. For the data analysis, MAXqD software was used.

UK and India were selected for the study since both show similar outcomes in creating smoke-free environments but differ in political structure and characteristics. In this study, a most different in type but similar outcome case design is adopted. A review of the institutional changes in these two countries will explain the similarities in the outcomes. Since historical institutional analyses lack a universal toolkit to analyze country policies, hypotheses are usually deduced by interpreting the empirical material before the analyses. The focus of the socio-historical comparative approach lies on stakeholders and stake challengers and the way that the power of these actors changes over time as a result of process changes (12). This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Ethics code no: IR.MUMS.FHMPM.REC.1402.032.

3. Results

In this study, 27 papers and 16 reports were reviewed. UK and India, having different backgrounds and country profiles, ratified FCTC. The total smoking prevalence among adults differed in these two countries (20.4 for males and 1.9 for females in India and 19.9 for males and 18.4 for females in the UK in 2018), although the difference was rather small (13). Understanding related institutional changes is necessary to identify and explain the factors that pose challenges to implementing tobacco control policies. Institutions structure the behavior; in every country, the structure of political institutions provides various interest groups with diverse veto points that need to be negotiated (14). In this part, the main actors and their power dynamics in the tobacco control process in the UK and India are reviewed and explained.

3.1. United Kingdom

The UK has a population of about 67 million and is a high-income country (15). It has a unitary governmental system in which political authority is concentrated in the central government. The UK has successfully controlled tobacco consumption and is considered one of Europe's countries with the strictest tobacco regulations (16).

Tobacco was brought to England by European adventurers in 1565, and it was criticized from the time it was introduced to the country. Still, the demand continued to grow, and very soon, plentiful tobacco supplies reached British shops. In the 1800s, smoking became a characteristic of a Victorian gentleman, and even smoking was compulsory at Eton Public School. After a while, anti-smoking campaigners made little headway; as a result, the Children’s Act of 1908 forbidding the sale of tobacco to children under 16 was passed. In 2002, Westminster passed a bill banning tobacco advertisements, and in 2006 passed a bill banning smoking in public places (17). In 2004, the UK ratified the FCTC (18) Other measures, such as smoking cessation initiatives and health education, were introduced very soon (17)

Public places with smoke-free legislation in the UK include health-care, educational, and governmental facilities, indoor offices, restaurants, cafés, pubs, bars, and public transportation. In the UK, fines for smoking are defined by law and can be imposed on the smoker and the establishment. All country is covered by subnational legislations, which WHO has assessed as complete. Furthermore, tobacco dependency rehabilitation is available in most health facilities, and National Health Services (NHS) covers all costs. The law requires health warnings on tobacco packages, whether domestically produced or imported. Based on national laws, tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship are banned, and tax is applied to the most popular brands of cigarettes. Also, a national tobacco control program and several anti-tobacco mass-media campaigns exist (18). In the UK, the smoking rate has considerably decreased in recent years (from 50% for men and 40% for women in 1974 to about 19% for both genders in 2015 and 2018) (19, 20).

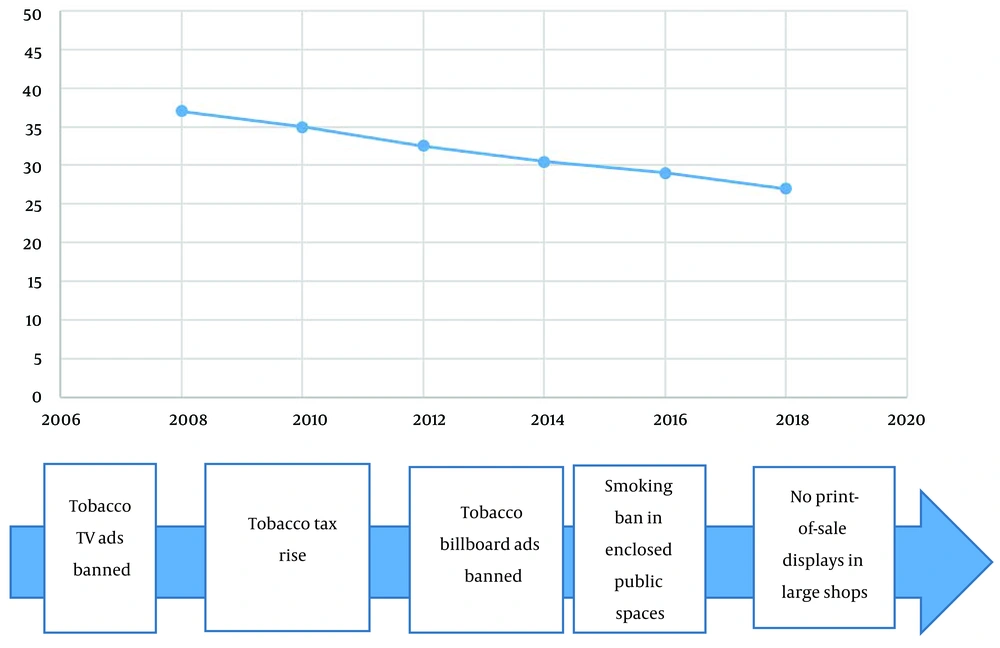

The move toward restrictive smoking policies started in the early 20th century in the UK. The demands of an institution, Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), and parliament members, following the constant production of evidence on the link between smoking and diseases, especially a document named “Smoking Kills,” forced the government to change its policies towards the tobacco industry. The ban on the sale of cigarettes to children (1903), the ban on cigarette advertising on TV (1965), health warnings on cigarette packs (1971), phasing out smoking in public transportation and cinemas, a tax increase on health grounds in the 1970s, Code of Practice on Smoking at Work, the Charter on Smoking in Public Places, and better customs controls show the change of government’s policies about tobacco (17). The UK smoking rates and evolving anti-tobacco measures can be seen in Figure 2.

3.2. India

India is the second greatest populous country, with a probable 1.2 billion people and the third largest economy in the world. Legislative authority and power in this country are implemented by the parliament, which has two houses: An upper house, the Council of States, and the lower house, or the House of People. Furthermore, due to its heterogeneity, India uses a central political structure whereby power is shared between the central government and 28 states (21).

About 400 years ago, tobacco was introduced to India by the Portuguese. They established the tradition of tobacco smoking and trade in this country. Two centuries later, commercially produced cigarettes were brought to India by the British, who established tobacco production (16). Soon, tobacco became an important item of trade. Surprisingly, given the amount of tobacco that India used to produce and still produces, little is known about the history of tobacco in India (22).

Globally, the dominant form of tobacco use is cigarette smoking. The main smoking method in India is Bidis smoking, and a great section of overall tobacco intake is the oral use of smokeless products (23). This country is home to over 195 million tobacco users. Tobacco consumption in India has been the second major globally, surpassed only by China (24). Tobacco-related habits among the Indian population show considerable variation by area and gender. The nature of sociocultural determinants and community responses to tobacco might have varied over time, region, religious denomination, and social class but always existed (25).

In the seventies, India gave conflicting signals about tobacco control. This time was marked by early attempts to enact tobacco control legislation, though they were not enough. In 1975, the Tobacco Board Act was introduced to develop the tobacco industry; it brought tobacco under the Central Government. The act facilitated the regulation of the production of tobacco. Moreover, the Tobacco Cess Act of 1975 aimed at collecting duty on tobacco for the development of the industry. Anti–tobacco advocates have criticized the Act because it nurtured the tobacco industry with loose export policies and subsidies. Their rationale was to keep the tobacco industry under control for the public well-being and interest (16).

During 1980 - 1990, civil society, mass media, and other agencies were more organized and important in promoting population awareness of tobacco-related health issues. This led to public litigation and favorable outcomes by courts and increased the pressure on the government to impose restrictions on the tobacco industry. Therefore, the demand for tobacco control increased at the Indian Parliament. Shortly after, regional and national consultations between a collective of organizations advocating tobacco control, the WHO, and the Indian Ministry of Health on “Tobacco or Health” took place. A while later, a memorandum was issued by the Cabinet Secretariat in 1990 that prohibited smoking in public places. It was the direct result of NGOs’ action, which set the judiciary of India’s thinking about the rights of non-smokers (26).

The most noteworthy law on tobacco control was the Cable Television Networks Amendment Act of 2000 which banned the transmission of tobacco on television across the country. In 2003, India took a more aggressive stance on tobacco control with the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (27) The Act was the result of expert consultations identifying tobacco as a “demerit commodity” (28).

Soon after committing to FCTC, the Indian government established National Tobacco Control Programs (NTCP). The programs aimed to establish tobacco cessation centers and educate healthcare workers, teachers, students, and the general population about tobacco health hazards. The programs included mechanisms for monitoring the enforcement of tobacco control legislation at a district level (29). Together with NGOs, the government made efforts to educate the Indian community, which, although few, have intensified in the past few years.

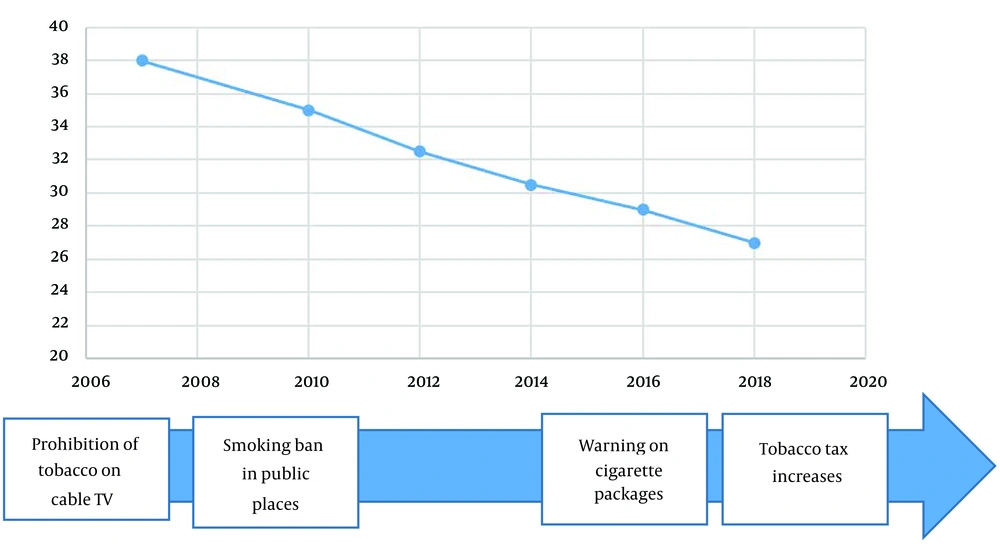

Efforts to ban smoking scenes in films have been challenged in Indian courts several times (27). Despite the difficulties, India has been praised for its achievements in implementing FCTC regulations and even became the convention coordinator for the South East Asia region (23). During 2011 - 15, India could lower tobacco use across different socio-economic groups. However, smoking is still the main cause of health inequality in this country (30). Figure 3 shows smoking rates in India from 2007 - 2018.

India smoking rate 2007 - 2018 (31)

4. Discussion

UK and India, having different backgrounds and country profiles, ratified FCTC. The policy outcomes in India show similarities with the smoke-free environment policy of the UK. In both countries, there has been a serious conflict between the interests of the tobacco industry and public health advocates. Three main phases of the group–government relations on tobacco control can be seen. In the first phase, post-World War II, the tobacco industry was dominant, and public health was excluded by the policy image of economic benefits and minimal knowledge of the link between smoking and diseases (17). The second phase is identifiable by more scientific research that established the link, but the response was mediated by a policy monopoly (26). At this time, competition among public health groups was minimal since they were not organized and their funding was low. In the current phase, public health groups are organized and respected within the government, and the tobacco industry’s power is at the lowest level.

Generally, specific founding moments of institutions direct countries to broadly different development paths. The case of tobacco control in both countries shows the strong lobbying of the tobacco industry. Over many years, the tobacco industry attempted to mislead politicians and the public and misused front groups and third-party advocates to limit and undermine tobacco control measures. The tobacco industry has tried almost everything, from claiming the right of smokers to freedom and the interests of small shopkeepers or pop landlords to sponsoring cultural events to maintain its position. This industry is still very strong, and it is difficult to limit its activities. Judge Gladys Kessler said in a judgment in 2006 that the tobacco industry leads to a surprising number of deaths per year, is responsible for an immeasurable amount of human suffering and financial loss, and is a heavy burden on our national health care system (32).

In a recent universal economic crisis, the tobacco industry has used various strategies to keep tobacco cheap. Scholars in the UK urge the government to increase the tax to limit the industry (33). Over the past 15 years, the literature on the impact of policy measures on tobacco control measures has grown significantly, providing a better basis for justifying specific measures. Tobacco tax hikes, enforcement of smoke-free aviation laws, blanket marketing bans, media campaigns, smoke-free policies, and strong health warnings play an important role in reducing smoking prevalence (34).

Policy implementation is intermediate between policy expectations and policy results. This gap is shaped by various factors resulting from policy content, the methods of policymaking, and how authority is used in health policy advocacy (10). The government and the national and global civil society groups play important roles in this regard. For appropriate policy implementation, it is crucial to understand how their effects are played out (e.g., in formulating policy) and the setting in which these different players and processes interact (35). Usually, changes in public attitudes do not directly affect public policies. It took a long time for medical spotlighting health risks of tobacco to be heard.

A representational community comprises the organized interests in a particular policy domain; the stakeholders who benefit from the status quo or are threatened by the revision, and stake challengers who are interested in changing the status quo because they do not benefit from it or are harmed by it. The representational community varies over time and across policy domains. The different attributes of stakeholders and stake challengers may be combined to produce four distinct representational communities. When stake challengers are absent and stakeholders are allied, the community is homogeneous and can be considered a block. The community may be complex and a mixture of interests if the stakeholders are competitive. On the other hand, a polarized community is formed when organized stake challengers face linked stakeholders. Where stake challengers are effectively present and stakeholders are competitive, the community becomes heterogeneous. It creates a network with broad boundaries where participants share opinions on the same issues in the policy domain (12). The power of stakeholders in the tobacco industry was weakened over time due to the increasing power of stake challengers interested in changing them. The stake challengers built a network of participants with a shared view on tobacco control. The network comprised civil society and medical professionals in both countries.

Initially, the interest groups advocating tobacco control in the UK and India were disorganized. The tobacco industry was powerful, and, to protect its revenue, it influenced the government’s decisions on tobacco control. Organizing interest groups in the UK started in the sixties, whereas the interest groups in India began forming in the seventies. Only after global pressure from World Health Assembly and especially WHO did the interest groups in India become uniform against the tobacco issue. Both countries had major ties with the tobacco industry and tried to balance the interests of the industry and anti-tobacco groups more in India than in the UK. An explanation could be that India's economy has been largely dependent on cultivating tobacco. Another explanation could be that the governmental power in the UK is more centralized than in India. The federal system in India permits differences in tobacco control enforcement over the states (36). Moreover, tobacco control advocacy groups tend to submit their ideas to state bodies first. In contrast, these ideas are more directly brought to the parliament in the UK. Similarly, in both countries, anti-tobacco interest groups and governments’ thoughts and ideas about tobacco control changed due to the increasing scientific evidence on the links between morbidity and mortality and tobacco use. However, funding was a problem for anti-tobacco groups in both countries. This positively changed in the UK but remained a problem for India. Moreover, funding makes tobacco control enforcement difficult in India. The tobacco industry has relatively more power in India than in the UK, and funding for anti-tobacco actions is less in India than in the UK. Smoking can be controlled through school or community education interventions and cessation support facilitated through providing training for health professionals and school teachers (28).

A summary of tobacco control policies in the UK and India is shown in Table 1, and a list of barriers and facilitators, similarities and differences in tobacco control in these two countries are provided in Table 2.

| United Kingdom | India | |

|---|---|---|

| History of tobacco | Tobacco introduced in 1565; Ratified FCTC in 2004 | Tobacco was introduced 400 years ago; Ratified FCTC in 2004 |

| Prevalence of tobacco use (%) | ||

| Before enforcement (2000) | 34.2 | 32.3 |

| After enforcement (2020) | 21.7 | 17.8 |

| Control measures under the FCTC policies | ||

| Reducing demand | Banning tobacco advertisement, promotion, and sponsorship; Health warnings on tobacco packages; Health education; Smoking cessation initiatives | Treatment of tobacco dependence; Health warnings on cigarette packets; Banning cigarette advertisement; Raising public awareness; Prohibiting tobacco on TV |

| Reducing supply | Ban the sale of cigarettes to children; Tax increase on cigarette; Customs controls | Ban the sale of cigarettes to children; Collecting duty on tobacco |

| Reducing second-hand smoke | Banning smoking in public places; Code of practice on smoking at work | Prohibiting smoking in public places; |

| Control measures under the FCTC | Fines for smoking levied on the establishment and smoker | Penalty for smoking in public places |

Tobacco Control Policies in UK and India

| United Kingdom | India | |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to tobacco control | Drastically reducing tobacco production costs, producing distinctive cigarettes tastes, promoting smoking as a stress-reducing pleasure, promoting individual choice and freedom of smokers, economic benefits of smoking and the rights of workers and owners of pubs and restaurants, high level of representational legitimacy and direct lobbying to senior ministers, undermining the health risks of smoking, gift coupons or sport sponsorship, promoting smoking as a modern code of behavior. | Tobacco lobby, large economic benefits of smoking, social and cultural factors, corruption subsidies to tobacco growers, worries about massive employment loss, government policy on developing the Indian tobacco market, The inadequate knowledge of people about their right to a smoke-free environment, claiming uncertainty about scientific facts on tobacco health risks, legal challenges brought about by the tobacco industry against anti-tobacco actions, financing and widely advertising non-tobacco goods with the same brand names, supporting bravery and film fare awards, the use of surrogate advertising methods and violating advertising regulations. |

| Facilitators | Increasing scientific evidence on the health risks of smoking, anti-tobacco mass media campaigns, advocacy by civil society, FCTC ratification and international movement. | Increasing scientific evidence on tobacco harms, litigation and favorable verdicts by courts against the tobacco industry, World Health Assembly, WHO, and NGOs’ actions, FCTC ratification. |

| Similarities | major ties with the tobacco industry, committing to FCTC, conflict of interests between the tobacco industry and governments’ public health authorities, similar pathway to control the tobacco industry. | |

| Differences | inadequate funding to anti-tobacco groups in India compared to the UK, Week enforcement of the tobacco control law and lack of mechanisms in India in comparison to the UK | |

Barriers and Facilitators, Similarities and Differences in Tobacco Control in UK and India

Acknowledging the important and incompatible conflict of interests between the tobacco industry and governments’ public health authorities, FCTC specifically states in Article 5.3 that member states should defend their public health strategies on tobacco control from the profitable interests of the tobacco industry. According to the critics, India has done little to address the conflict of interests because the Tobacco Board established under the Tobacco Board Act in 1975 has not been dismantled to promote the interests of tobacco growers and develop the tobacco industry (37).

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study explained the situation of different stakeholders and interest groups over time. This type of information is necessary for making successful policies. However, every country has specific cultural, political, and economic characteristics, and the findings of this paper cannot be generalized to other countries. This shows the necessity of a comprehensive view of all interest groups in a policy domain.

4.2. Conclusions

This paper demonstrated how the tobacco industry, interest groups, and people interact for the benefit of tobacco. UK and India have major ties with the tobacco industry; they are committed to FCTC and face challenges about the conflict of interests between the tobacco industry and public health authorities. They have followed a similar pathway to control the tobacco industry. However, inadequate funding available to anti-tobacco groups and weak enforcement of the tobacco control law can be seen in India in comparison to the UK. To fulfill the FCTC obligations, the governments should make a balance between the main actors in favor of people’s health. They are not helpless! They have the capabilities needed to limit industries harming people’s health. Governments should carefully recognize the stakeholders and stake challengers in a specific policy domain and balance their interests. Health policymakers should be sensitive to the power balance between main stakeholders and how their actions affect people’s health. Education plays an important role in changing the behavior of people. They should know about the health risk of smoking and their right to a smoke-free environment. People who are educated about a particular health policy will support the government. Interest groups should be organized and get stronger to be able to influence such a powerful industry.