1. Background

The global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has posed many challenges to policymakers and health officials, forcing them to adopt emergency policies across a range of sectors to control the disease (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged the collaboration between health and other related sectors as a prerequisite for adopting these policies (2). Health has been progressively considered a pillar for sustainable development. Hence, there exists the need to include health in all policies (3). In this regard, some countries have introduced and focused on the “whole-of-government” (WoG) approach, in which sectors beyond health have to work across boundaries to achieve an integrated government response to particular issues, such as global health emergencies (4). Besides, the “whole-of-society” (WoS) approach, in which communities are at the center of response, is vital for effectively dealing with crisis. Indeed, communities need to be engaged and empowered to take appropriate decisions and measures during emergencies, as well as other occasions (5).

World Health Organization’s definition of WoG denotes public service agencies working across portfolio boundaries to achieve a shared goal and an integrated government response to particular issues (6). Achieving coordination within and between organizations and strengthening departments’ ability to perform as one system instead of a collection of separate components are among the most notable purposes of applying the WoG approach. This approach is a joint effort between government agencies to make the most of all available resources (7). Additionally, the WoS approach means involving all stakeholders, including civil society, communities, academia, media, private sectors, voluntary associations, families, and individuals in the policy-making process to strengthen the resilience of communities and society (8).

The combined WoG-WoS approach renders governmental and societal solidarity to tackle global health emergencies such as pandemics (9). In addition to various ministries and government agencies, efficient engagement of academia, community stakeholders, private enterprises, and citizens is essential for the effective management of pandemics (10). For instance, academia is a main player in promoting evidence-based policymaking and preventing the formation of contradictory policies (11, 12). Furthermore, inter-academic collaborations and their partnership with other sectors, including health authorities, for example, through conducting epidemiological studies for predicting the pattern and trend of various diseases (7), are crucial for strengthening health systems in prediction, preparation and dealing with microbiological and other health threats worldwide (13).

In addition to governments' efforts, the WoS approach highlights public participation as a key to developing effective actions to control the epidemic and manage its far-reaching consequences in times of outbreak (14). This approach acknowledges and promotes the full and effective contributions of all relevant stakeholders to the risk management of emergencies (12). Despite WHO’s emphasis, the WoG-WoS approach has not been fully considered by many governments, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), to combat the current COVID-19 pandemic. This paper highlights the importance of paying attention to the WoG-WoS approach for strengthening policymakers’ decisions in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis in Iran.

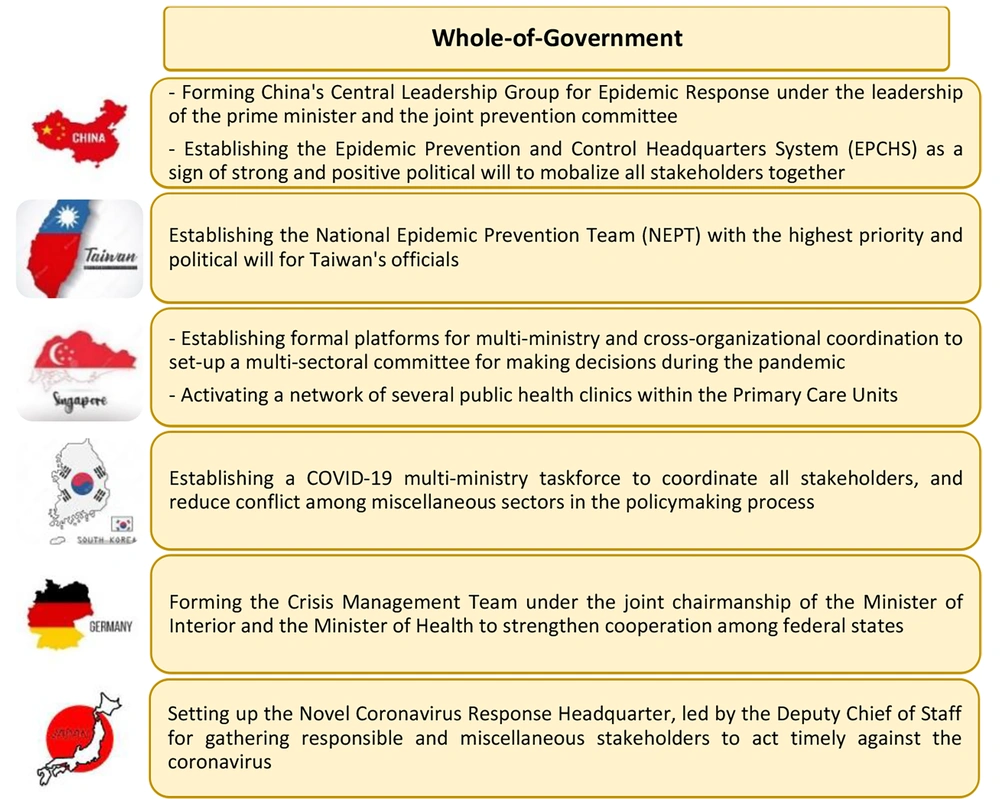

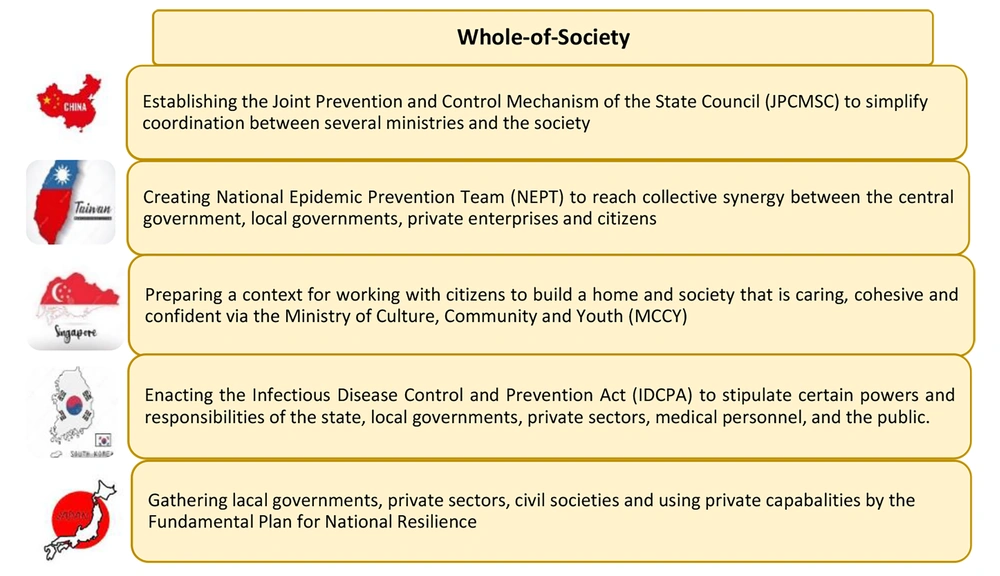

2. The Global Implementation of WoG-WoS Approaches

Countries have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic based on their context and health system infrastructures. Some countries designed appropriate structures to apply the WoG-WoS approach to help combat the crisis (Figures 1 and 2). For instance, in Singapore, the government took the most advantage of enhancing inter-sectoral collaborations between ministries and organizations by defining effective platforms and developing various inter-sectoral task forces (1). They also adopted a WoS approach, with a particular focus on supporting the vulnerable population of foreign workers, who comprised the majority of the country's COVID-19 cases (4). To establish a WoG approach in China, the State Council created a platform for communication, cooperation, and resource mobilization among 32 ministries and departments, the so-called Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism (2). China also implemented WoS measures through the participation of social organizations and the engagement of citizens in the pandemic prevention and control (3). Evidence suggests that countries that have applied the WoG-WoS approach could have dealt more efficiently with the crisis (Figure 1 and Table 1).

| Total Cases | Total Deaths | Total Cases/1 m Population | Total Deaths/1 m Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 664 121 509 | 6 706 674 | 83 274 | 0.27 |

| China | 10 566 576 | 32 524 | 1 399 | 0.01 |

| Taiwan | 9 055 191 | 15 542 | 378 983 | 1.61 |

| Singapore | 2 208 216 | 1 713 | 391 734 | 0.05 |

| S. Korea | 29 539 706 | 32 625 | 570 090 | 0.97 |

| Germany | 37 509 539 | 162 688 | 449 917 | 2.10 |

| Japan | 30 495 711 | 59 830 | 246 028 | 2.66 |

3. Iran’s Experience in Taking Whole-of-Government and Whole-of-Society Approach

Besides its health dimensions, the COVID-19 crisis is a socio-political challenge, tackling which requires complex multisectoral interactions. Despite advances in access to effective vaccines and treatment, many countries, particularly in the LMICs, have not yet fully reached herd immunity; hence, it is imperative to continue preventive policies, i.e., social distancing, wearing masks, and isolation, to control the virus transmission. Implementing such restrictive strategies can be elusive without decisive leadership and consensus of all government agencies and relevant stakeholders, and failure to do so can lead to political, social, economic, and related medical difficulties (7, 15, 16). In Iran, where the pandemic crisis coincided with the toughest unilateral political and economic sanctions, implementing such strategies could be elusive without a tailored WoG-WoS approach to include citizens in decision-making as well as provide effective socio-economic support, particularly for the vulnerable population (17, 18). Indeed, strong and meaningful inter-sectoral collaboration and the engagement of all relevant stakeholders, i.e., economics, finance, trade, education, social security and welfare, nutrition, justice, etc., is the key to overcoming the crisis.

4. The Whole-of-Government Approach in Action

Following the official announcement of the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran on February 19, 2019, and the need for a collective synergy among all government sectors and society, the outbreak reached the highest political priority (19). The multi-sectoral National COVID-19 Committee (NCC) was established during the first days of the pandemic, comprising a range of relevant ministries and other departments (Table 2) (19). This was the initiation of inter-sectoral collaboration and implementation of the WoG approach to combat COVID-19 in Iran. Iran has a centralized government, and all rules and regulations are issued by the central government and implemented throughout the country. Therefore, NCC has the main responsibility of responding to the outbreak in the country via the issuance of mandates throughout the country. The NCC approved several preventive measures, including the closure of schools, educational centers, shopping centers, borders, and bazaars, as well as the cancellation of public events, including Friday prayers and religious and funeral ceremonies, and restriction of internal and international travels to control virus transmission (18). Nonetheless, Iran has faced seven waves of the COVID-19 pandemic so far, each one more devastating than the previous wave. The inadequate political will to fully implement the WoG-WoS approach in the right manner might be the main reason, we believe, that compelled Iran to face more severe consequences compared to some other countries (20-22). For instance, no public representative was a member of the NCC, and the capacity of civil society was not meaningfully utilized to reach people for training and preparation. Moreover, disappointingly, the NCC believed that herd immunity would protect most exposed to the virus (23, 24).

| Position in the NCC | General Position | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chairman of the National COVID-19 Committee | The president |

| 2 | Secretary of the National COVID-19 Committee | Director of National Board for Medical Education |

| 3 | Chairman of the Social and Disciplinary Committee | Interior Minister |

| 4 | Chairman of the Committee for the Prevention of Pollution of the Transport Fleet and Passenger Gathering Authorities | Minister of Road & Urban Development |

| 5 | Chairman of the Education Committee | Minister of Education |

| 6 | Chairman of the Committee for Supervision of Gatherings Centers | Minister of Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism |

| 7 | Chairman of the Information Committee | Minister of Culture & Islamic Guidance |

| 8 | Chairman of the Committee for Supervision of Pilgrimage Centers and Holy Shrines | Head of Hajj and Pilgrimage Organization |

| 9 | Member of the committee | Chief of General Staff of the Armed Forces |

| 10 | Member of the committee | Attorney General (Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) |

| 11 | Member of the committee | Chief of Planning and Budget Organization |

| 12 | Member of the committee | Chief of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting |

| 13 | Member of the committee | Minister of Science, Research and Technology |

| 14 | Member of the committee | Spokesman for the Government of Iran |

| 15 | Member of the committee | Commander of the police force of the Islamic Republic of Iran |

| 16 | Member of the committee | A member of the Constitutional Council |

Abbreviation: NCC, National COVID-19 Committee.

Multi-sectoral collaboration is the key to the fight against the complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the NCC had diverse membership, it did not establish formal multidisciplinary working groups that represent all relevant sectors and stakeholders for providing evidence-informed and efficient strategies (18). Most notably, as the symbol of multisectoral collaboration for health, the capacity of the Supreme Council for Health and Food Security (SCHFS) was not meaningfully utilized in materializing the WoG-WoS approach. Chaired by the president and its secretariat within the MOHME, the SCHFS has the potential to align the private sector and community representatives for the policy-making process, for instance, through the establishment of national and sub-national health assemblies. Such capacity for bringing people into decision-making for health, applying health in all policies, and fostering the WoG-WoS approach was not meaningfully utilized to control the crisis (25).

COVID-19 was, especially during its first 18 months into the pandemic, full of obscurities. Hence, the need to produce reliable evidence in biological, social, human, and other aspects is vital to combat the pandemic. Academic institutions are at the center of producing evidence (26, 27). In this regard, the scientific sub-committee of the NCC was set up to use scientific evidence in formulating COVID-19 policies. Nonetheless, the composition of the sub-committee was skewed towards a few selected clinicians and epidemiologists, where other relevant expertise, including health economics, health policy, public policy, psychology, sociology, communication science, information technology, etc., were overlooked (2). The NCC did not establish an organic communication line with the National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR), which is the health system observatory of Iran, for producing evidence and regular monitoring of the implemented strategies (2). More disappointingly, the capacity of the extensive primary health care (PHC) network was not fully utilized to bring COVID-19 services closer to the communities, conduct effective tracing and testing, and reduce hospitalization (28).

5. The Whole-of-Society Approach in Action

Whole-of-society approach can help resolve many health challenges effectively by bringing representatives from civil societies, scientific bodies, the private sector, media, etc., into the policymaking forum (2). COVID-19 is a multidimensional challenge that involves all sections of society. Engaging with all is essential to tackling the pandemic (29). Further, individual, family, and community contributions can lead citizens to be involved in decision-making, which will facilitate better implementation of disease control policies (30, 31). Despite health system authorities’ efforts to enhance public involvement, the magnitude of social participation in health promotion is far from perfect in Iran (32). The COVID-19 crisis was not an exception, as the NCC did not manage well to engage with the representatives of civil society and the grassroots organizations, i.e., the Supreme Council of Provinces, the Strategic Council of Non-governmental Organizations, for mitigation and control of the pandemic. Insufficient community engagement and inadequate public healthcare literacy might have created remarkable difficulties in public adherence to preventive protocols, keeping social distancing and citizens’ compliance with the lockdown requirements in Iran (33-35), and the frequent inevitable, devastating waves of the pandemic after that.

6. Policy Recommendations

COVID-19 was not the first crisis, and it would not be the last. Although the pandemic is now under control in the world, it has opened a window of opportunity for governments to learn lessons and prepare themselves for future crises of any kind. The WoG-WoS approach is key to navigating through any crisis, including the recent COVID-19 pandemic and its dramatic consequences. Therefore, in line with the global experience and the context of Iran, we advocate the following:

- Obtaining the utmost political support to apply the principles of good governance, i.e., public participation, transparency, responsiveness, use of evidence, and accountability, into the health system of Iran.

- Fostering meaningful intersectoral collaboration, with the effective participation of relevant government sectors, private enterprises, and citizens, through strengthening the SCHFS and organic relationship with academia and the media, as well as applying system thinking in planning for health before, during, and after any crisis.

- Ensuring public participation from all public agencies, including but not limited to food, agriculture, business, economic, philanthropic organizations, and the entire public as a whole for decision-making for health.

- Investing in macro health monitoring and the use of big data tools and artificial intelligence in surveillance, prediction, and preparation for pandemics, along with acquiring political support for strengthening the Center for Disease Control affiliated with the MOHME.

7. Conclusions

In addition to appropriate preventive and curative measures, effective and targeted public health emergency governance is essential to deal with outbreaks. The WoG-WoS approach is an effective governance strategy to engage with all government sectors, institutions, governmental and non-governmental organizations, and, more importantly, all citizens as the pillar of society. Countries with better performance in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis have benefited from societal mobilization and meaningful engagement with all sectors, including both state and non-state actors. The COVID-19 pandemic and its long-term consequences have not been fully overcome yet, and future pandemics are likely to happen. Lessons learned from this crisis are ample to wake up politicians and policymakers at midnight to invest in tailored, timely, and efficient mechanisms to foster the WoG-WoS approach in preparation for future global health crises, now more than ever.