1. Context

Health, in all its aspects, is a fundamental human right. Health and welfare organizations worldwide strive to achieve the best health outcomes possible for their societies (1). Various determinants of people's health have a complex relationship with other cultural and social properties of a community, leading to health inequities (2). According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), “social determinants of health (SDH) are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life, including income and social protection, education, employment, and job security, working life conditions, food security, housing, basic amenities, environment, early childhood development, social inclusion and non-discrimination, structural conflict, and access to affordable health services” (3).

Prioritizing women's health is crucial to achieving the fourth and fifth Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (4).Women's health is influenced by physical, mental, sociocultural, and spiritual dimensions that are determined by the biological, social, political, and economic background of the community. It is important to consider the life cycle chart of women to promote their health in all dimensions (1).

Sexual and reproductive health are two approved goals of the world plan for sustainable development (5). The WHO emphasizes reproductive health as the main and basic part of well-being. People should have a responsible, satisfactory, and safe sexual life and freedom in reproductive ability and decision-making. Additionally, they should have access to safe, cost-effective, and acceptable ways for family planning (6).

Studies have shown that social determinants of health have a severe impact on the treatment of gynecological diseases, such as premature labor, unwanted pregnancy, infertility, cancers, and maternal mortality (7). Reproductive health impairment is responsible for 15% of the total burden of diseases and leads to women's disabilities around the world, accounting for 21.9% of DALY per year for women (8). The WHO has developed a framework to recognize opportunities and threats to encourage sexual and reproductive health services with high quality and accessibility (9).

2. Objectives

Through the current study, we aimed to identify and stratify the social determinants that are effective on women's reproductive health in order to design better interventions and plans to improve these issues more effectively and equitably.

3. Methods

The present study is a systematic review of all valid and available evidence on the social determinants affecting women's reproductive health, published between 2010 and 2019. All studies meeting the inclusion criteria were collected within this timeframe.

Inclusion criteria consisted of articles published in Persian and English languages, databases that could be fully accessed, and articles with accessible full texts. The screening was conducted in multiple stages, and cases that aligned with the research question and purpose in terms of title, abstract content, or the entire article and scored the necessary points in the critical evaluation stage were included in the study.

A structured question was designed using the PICO framework:

P: Women

I: Social components

C: -

O: Reproductive health

Data collection involved an initial search of sources to determine keywords related to the research topic. Keywords included (social), (determinant/indicator/index/indices/marker), (reproductive health/fertility/child bearing), and (women/female/woman). Authentic medical sites and databases, such as PubMed, Scopus, and ISI, and internal databases, such as IranDoc and SID, were searched using these keywords, and a specific search strategy was used for each database (Table 1).

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Social” [tiab] AND (“determinant” [tiab] OR “indicator” [tiab] OR “index “[tiab] OR” indices “[tiab] OR “marker” [tiab]) AND (“reproductive health” [tiab] OR “fertility” [tiab] OR “child bearing” [tiab]…) AND (“women” [tiab] OR “woman” [tiab] OR “female” [tiab]). *No filters were applied to increase search sensitivity except for the year of publication (2010 - 2019) |

| Scopus | ((ALL (social)) AND (ALL (determinant OR indicator OR index OR indices OR marker)) AND (ALL (reproductive health OR child bearing OR fertility)) AND (ALL (women OR female OR woman)) AND pubyear 2010 - 2019) |

| Web of knowledge | (Ts = (determinant OR indicator OR index OR indices OR marker) AND (TS = (reproductive health OR child bearing OR fertility) AND (TS = (women OR female OR woman)) AND (TS = (social). Refined by: Publication Years: (2019 OR 2018 OR 2017 OR … OR 2010) |

Articles and studies on the social determinants of women's reproductive health were collected using EndNote 8 software, and numerous sources were reviewed based on the title of the research or article. The articles were separated by relevant titles and according to the keywords. At this stage, the extracted articles were reviewed by two independent researchers in terms of the content of the abstract to ensure alignment with the research objectives and keywords. Articles with relevant abstracts were included for full review. The search was then conducted to find the full text of the included articles in the previous step, and articles with available full text were selected for the next step. The full text of the articles was reviewed separately by two independent researchers, and articles that aligned with the research objectives advanced to the next stage. Cases that were not agreed upon by both researchers in the previous steps were re-examined and resolved by a third party. The articles were then reviewed and scored in terms of quality and accuracy using the CASP and STROBE tools for each type of study. Articles with a score above 75% entered the final stage of the study.

4. Results

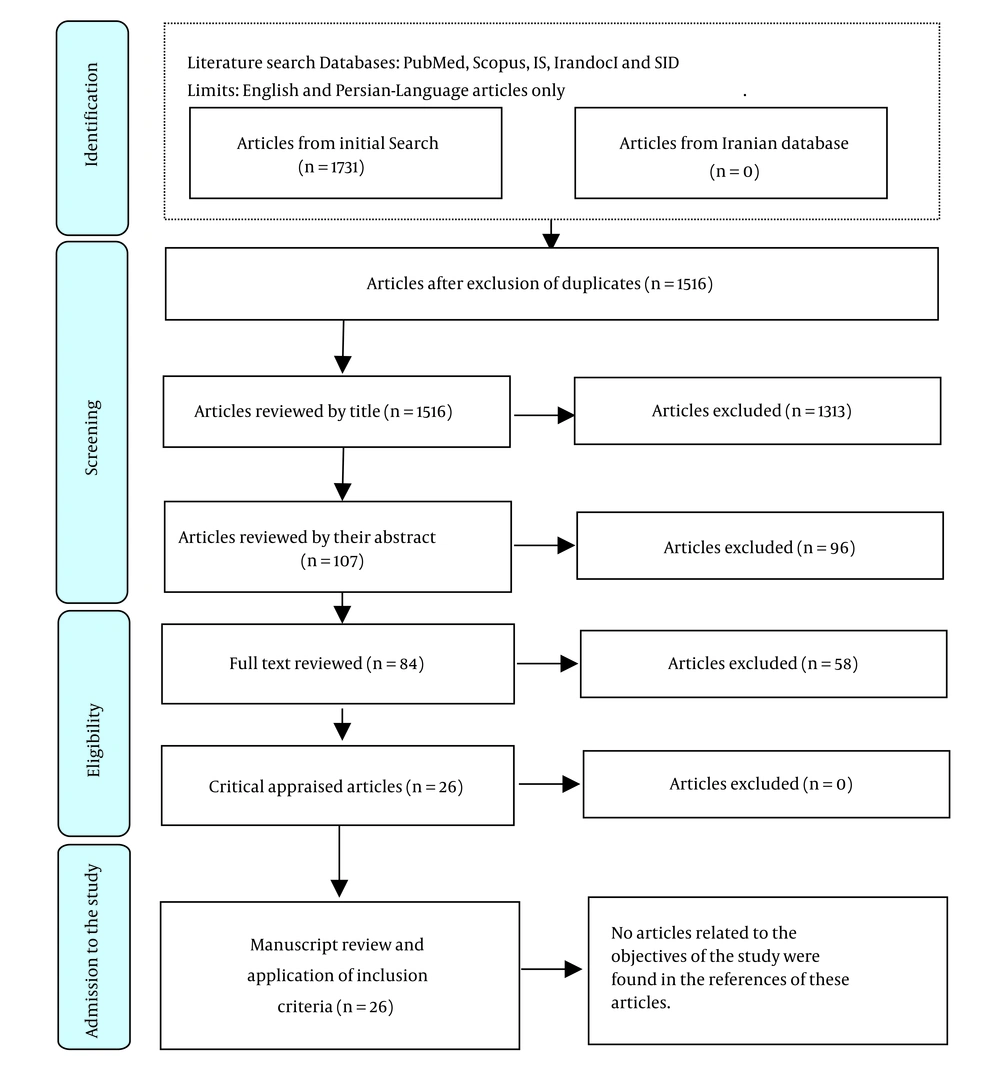

In the initial phase of database searching, 1731 articles were obtained, but no relevant articles were found in Iranian databases. After removing the duplicates (215), 1516 articles remained. These articles were screened for title alignment with the research questions and objectives, resulting in the exclusion of 1313 articles. The remaining 203 articles were screened for abstract alignment, resulting in the exclusion of 3 articles due to lack of abstracts, 1 article due to non-Persian and English language abstracts, and 92 articles due to lack of content relevance. One hundred seven articles were selected for full-text review, but 13 articles were excluded due to unavailability of the full text.

Eighty-four articles remained for full-text review and compliance assessment with the research, resulting in the exclusion of 58 articles and the inclusion of 26 articles for critical appraisal. These 26 articles included 1 qualitative study, 19 cross-sectional studies, 1 review, 2 systematic reviews, 2 cohort studies, and 1 case-control study. Cross-sectional articles were reviewed using the STROBE tool, while other articles were assessed using the CASP critical appraisal lists, with all scoring above 75% and entering the final stage of data extraction.

The extracted determinants were categorized into four subgroups related to reproductive health:

(1) Fertility, which was directly mentioned in articles code 2, 4, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15.

(2) Family planning, which affects reproductive health and fertility, was discussed in articles code 1, 6, 7, 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20.

(3) Teen motherhood and pregnancy, which can indirectly affect reproductive health, were discussed in articles codes 3, 5, 21, and 22.

(4) Healthcare equity, which has effects on various aspects of reproductive health over short, medium, or long durations, was discussed in articles code 8, 10, 23, 24, 25, and 26.

Social determinants should affect reproductive health through direct or proximate components, including sexual activity (start time and frequency), contraceptive use (family planning), and history of complete pregnancy and full-term birth (10). The social indicators and components and their effects on reproductive health are presented in Tables 2-5, according to the groups defined above. Please see Appendix 1 for details of the extracted articles and data. The PRISMA diagram illustrating the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

| Reproductive Health Components | Main Social Determinant with Significant Effect | Subgroup Determinants | How to Affect | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premature marriage or sexual activity (reduction of reproductive health level) | Family environment | Family support | Risk reduction (protective effect) | (2) |

| Better monitoring by parents | Risk reduction (protective) | |||

| To use the mother tongue at home | Risk reduction (protective) | |||

| Better adherence to school | Risk reduction (protective) | |||

| Living with both biological parents | Risk reduction (protective) | |||

| Higher level of education | Risk reduction (protective) | |||

| Separation from family due to immigration laws | Increased risk | |||

| High-risk behaviors in other family members | Increased risk | |||

| Family cohesion | Risk reduction (protective) | |||

| Living | Living in a camp | Risk reduction (protective) | ||

| The high density of poverty in the neighborhood | Increased risk | |||

| Immigrants’ generation | Later generations | Risk reduction (protective) | ||

| Mother desired number of children (childbearing rate) | Women empowerment index | Higher index | Increased childbearing | (4) |

| Household empowerment index | Higher index | Increased childbearing | ||

| level of husband education | Higher level of education | Increased childbearing | ||

| Family size in the Residence area | Larger size of family | Increased childbearing | ||

| Religion | Islam-Christianity (in Burkina Faso) | Increased childbearing | ||

| Reproductive health in African-Americans | Racism | Sexual abuse and violence against black women for various non-economic purposes | Decreased fertility over time | (11) |

| Sexual abuse of black women to increase fertility and increase the number of slaves | Decreased fertility over time | |||

| Persistence of poverty in generations | Decreased fertility over time | |||

| Lack of access to equitable healthcare facilities | Decreased fertility over time | |||

| Changes in fertility rate and pattern in women | The age of women at the time of this study | Older at the time of study | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | (12) |

| Age of onset of sexual activity | Increasing age, especially after the age of 20 | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| Age at first marriage | Older age at first marriage | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| Level of Education | Higher level of education | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| The ideal number of children from the perspective of women | More ideal numbers | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| The rate of receiving family planning messages from social media | Higher receiving messages and family planning training | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| Residence | Living in urban areas | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| Household welfare index | Higher welfare index | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| The rate of use of contraceptive methods | Increasing the use of contraceptive methods during the time faster than other components | Reduction of fertility and childbearing | ||

| Proximate determinants of Reproductive health: TFR and DFS | Household welfare index | Higher welfare index | TFR, DFS reduction | (13) |

| Couples' level of education | Higher level of education | TFR, DFS reduction | ||

| Residence | Living in urban areas | TFR, DFS reduction | ||

| Race and ethnicity | Black race | TFR, DFS reduction over time | ||

| Fertility impairment | Level of education in women | Higher level of education | Higher rate of impairment (fertility reduction) | (14) |

| Fertility and childbearing rate | Macro and microeconomic determinants | Higher overall household expenditure | Reduction of childbearing | (15) |

| The higher per capita cost of education | Reduction of childbearing | |||

| Higher average level of house rent in the region | Reduction of childbearing | |||

| Decimal of household income | No significant effect | |||

| Other determinants | Higher level of wife’s education | Reduction of childbearing | ||

| Higher average size of family in the residential area(province) | Increasing of childbearing | |||

| Having one or more living son in the family | Reduction of childbearing | |||

| Higher Sunni population in the region | Increasing of childbearing | |||

| Higher rate of polygamy in the region | Increasing of childbearing |

Abbreviations: TFR, total fertility rate; DFS, desired family size.

| Reproductive Health Components | Main Social Determinant with Significant Effect | Subgroup Determinants | How to Affect | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced abortion or pregnancy termination rate | Religion | Buddhist | Abortion, childbearing | (1) |

| Higher level of education | Higher than high school, etc. | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Find out more about legal abortion cases. | Abortion, childbearing | |||

| Knowledge of safe and hygienic abortion sites | Higher knowledge | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Age | Women aged 25 - 34 | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Household wealth | Highest quintile | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Lowest quintile | Abortion, childbearing | |||

| Induced abortion or pregnancy termination rate | National income level | Higher national income level | Abortion, childbearing | (16) |

| The existence of detailed monitoring and inspections in public health system | Abortion, childbearing | |||

| The rate of employment of women in society | Higher rate of women's employment | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Residence | Living in an urban area | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Indigenous or immigrant population | Immigrants | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| The extent of access to Health services | Higher access to Health services | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| Age at pregnancy | Age lower than 20 | Abortion, childbearing | ||

| The existence of approved and guaranteed laws about abortion | Abortion, childbearing | |||

| Induced abortion or pregnancy termination rate | Women's education level | primary and higher level of education | Abortion | (17) |

| Age during pregnancy | Older age | Abortion | ||

| Employment status of women | Working women | Abortion | ||

| Religion | Christianity | Abortion | ||

| Utility of mass media | Increase the use of mass media | Abortion | ||

| Marital status | Married women | Abortion | ||

| Having control over the birth rate in women (Improving reproductive health despite reduced fertility) | Women's authority in decision making | Higher authority | Improved reproductive health | (6) |

| Age | Higher age | Improved reproductive health | ||

| Number of children in the family | Less than 2-3 children | Improved reproductive health | ||

| Access to maternal care services | Better access to services | Improved reproductive health | ||

| Rate of using family planning services | Couple agreement on the decisions | Disagreement | Usage, childbearing | (7) |

| Religious beliefs | Usage, childbearing | |||

| Fear of adverse effects of family planning processes | Usage, childbearing | |||

| Distance from family planning service centers | Longer distance | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Rate of using modern contraception | The average age of marriage in the community | Higher average age | Usage, childbearing | (9) |

| The average age at birth of the first child in the community | Higher average age | Usage, childbearing | ||

| The average age of onset of sexual activity in the community | Higher average age | Usage, childbearing | ||

| The average ideal number of children in a family in the community | Higher average | Usage, childbearing | ||

| The average duration of mass media use in the community | Higher average | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Average score of family authority in decision-making in the community | Higher average | Usage, childbearing | ||

| The average level of women's education in the community | Higher average | Usage, childbearing | ||

| The average scale of household welfare in the community | Higher average | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Distrust about sexual partner violence in the community | Higher level of distrust | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Rate of using modern contraception | Residence | Living in an urban area | Usage, childbearing | (18) |

| Women's education level | Higher level of education | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Family income level | Higher level of income | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Rate of using modern contraception | Woman's age | Age 25-35 | The highest rate of usage | (19) |

| Socio-economic status of the household | Lower SES of household | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Socio-economic status of the province of residence | Lower SES of the province of residence | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Having at least one son in the family | Usage, childbearing | |||

| Number of children in the family | Higher Number of children (more than 2 - 3) | Usage, childbearing | ||

| Rate of using LARCs | Woman's age | Age group under 35 | Usage | (20) |

| Deciding to have a child in the future | Usage | |||

| Number of children in the family | Less than or equal to 2 children | Usage | ||

| Husband's education level | Higher level of education | Usage | ||

| Occupational status of the husband | Low-level jobs and husband's unemployment | Usage | ||

| Welfare status of the family | The lowest welfare quintile | 40% reduction in use rate compared with the highest quintile |

Abbreviation: LARCs, long-acting reversible contraceptives.

| Reproductive Health Components | Main Social Determinant with Significant Effect | Subgroup Determinants | How to Affect | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teen pregnancy and childbearing | Monthly family income | Higher monthly family income | Pregnancy and childbearing | (5) |

| Marital status | A teenage girl who is married | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Age | Age group 18 to 19 years | The highest rate of pregnancy | ||

| Communicating with the family about reproductive health issues | Existence of desirable and effective communication | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| History of teen pregnancy in mother | The existence of a positive history in the mother | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Teen pregnancy and childbearing | Couple age gap | Lower gap | Pregnancy and childbearing | (3) |

| Level of women’s education | Uneducated | 5 times increasing in Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Level of husband’s education | Higher level of education | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Household welfare index | Lowest welfare index | The highest rate of teen Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Residence | Different rates in different areas | |||

| The extent of access to mass media | Higher access to mass media | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Time of data collection in the study | Reduction of pregnancy and childbearing over time | |||

| Teen pregnancy and childbearing | Socio-economic status | Lower socio-economic class | Pregnancy and childbearing | (21) |

| Employment status | Unemployment | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Family income | Lower level of family income | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Level of Education | Lower level of education | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Deprivations in the place of residence | Pregnancy and childbearing | |||

| Physical disorders in the neighborhood | Pregnancy and childbearing | |||

| The rate of income inequality in the place of residence | Increasing inequalities | Pregnancy and childbearing | ||

| Teen pregnancy and childbearing | Deprivation measured by the employment index | Increasing deprivation in any of the dimensions:Pregnancy and childbearing | (22) | |

| The Carstairs index measures deprivation. | Excessive family density in confined spaces | |||

| Not having a personal car | ||||

| Unemployment of men of the family | ||||

| Lower social class | ||||

| Deprivation measured by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation | Family income | |||

| Employment status | ||||

| Level of education | ||||

| General health status | ||||

| Access to services | ||||

| Housing situation | ||||

| Crime |

| Reproductive Health Components | Main Social Determinant with Significant Effect | Subgroup Determinants | How to Affect | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women's knowledge and utility of sexual and reproductive health services (in immigrants) | Age | 46 years and older | The least utility | (8) |

| Marital status | Not married | Lower utility | ||

| Migration time | Immigration in recent years | Higher utility | ||

| Cash reserves | Lack of cash reserves | Lower utility | ||

| Status of social capital | Lack of trust in others | Lower utility | ||

| Dominance of bounding relationships | Lower utility | |||

| Knowledge about sexual health and fertility | Lack of knowledge | Lower utility | ||

| Women’s utility of antenatal care | Urbanicity | Living in an urban area | Higher utility | (10) |

| Household welfare index | Medium and high welfare index | Higher utility | ||

| Women's education level | High school and higher education | Higher utility | ||

| History of contraception before pregnancy | Positive history of contraception before pregnancy | Higher utility | ||

| Deciding to have more children in the future | The decision not to have more children | Higher utility | ||

| Women's decisions about Their reproductive health: Deciding about sex, deciding on the use of condoms, decision-making index for reproductive health | Residence | Living in a rural area | Reduction in all dimensions of decision-making score | (23) |

| Household welfare index | Higher welfare index | Higher scores in all dimensions of decision-making | ||

| Age | Ages 15 to 19 | The least decision-making score | ||

| 20 years and older | Increasing in all dimensions of decision-making score | |||

| wife’s education level | Higher level of education | Higher scores in all dimensions of decision-making | ||

| Husband's education level | Higher level of education | Higher scores in all dimensions of decision-making | ||

| Religion | Islam | The least decision-making score | ||

| Inequality in the use of Antenatal care: Less than 4 prenatal visits, low-skilled midwife | Residence | Living in a rural area | Higher inequity, lower utility | (24) |

| Income level | Lower-income | Higher inequity, lower utility | ||

| Parity | Third and more | Higher inequity, lower utility | ||

| Level of education | Illiteracy | Higher inequity, lower utility | ||

| Inequality in the use of reproductive health services and antenatal care | Residence | Living in a rural area (lower economic class) | Increasing inequality - reducing service use (lower level of reproductive health) | (25) |

| Socio-economic status | Registered caste or tribe | Decreasing inequality - more service use (higher level of reproductive health) | ||

| Gender | Female | Increasing inequality - reducing service use (lower level of reproductive health) | ||

| Level of education | Lower level of education | Decreasing inequality - more service use (higher level of reproductive health) | ||

| Age | Adolescence age group (10 - 19 years) | The highest inequality (the least service use and lower level of reproductive health) | ||

| Religion | Islam | The highest inequality (the least service use and lower level of reproductive health) | ||

| Inequality in the use of reproductive health services and antenatal care | Wealth index | Lower index | Increasing inequality - reducing service use (lower level of reproductive health) | (26) |

| Residence | Living in a rural area | Increasing inequality - reducing service use (lower level of reproductive health) | ||

| Level of education | Lower level of education | Increasing inequality - reducing service use (lower level of reproductive health) |

5. Discussion

Indicators that affect the early onset of sexual activity and early marriage can also impact other factors, such as early pregnancy, induced abortion rates, and contraceptive use, ultimately affecting reproductive health and fertility rates. Indicators such as adolescent pregnancy and early motherhood, while potentially increasing fertility rates, can paradoxically decrease maternal and child care and reduce overall reproductive health. Therefore, all physiological and socio-economic components of reproductive health and childbearing are interconnected.

In this section, we can integrate the previous classifications to understand the results of the studies better and mention the determinants in general.

5.1. Social Determinants That Affect Reproductive Health Status (Regardless of the Rate of Childbearing)

5.1.1. Immigration

A higher level of education in the family, high levels of support and family cohesion, favorable access and compliance with the school environment, and living with other immigrants can have a protective effect against sexual activity or early marriage, improving reproductive health (10). However, immigrants generally have lower levels of reproductive health (16).

5.1.2. Education Level in Women

Reproductive disorders have been observed in women with higher levels of education. However, due to less access to reproductive health services in uneducated and low-educated women, their reproductive health status is not favorable (11, 20).

5.1.3. Ethnic-Racial-National Discrimination

Minorities generally have lower levels of reproductive health. Blacks in the United States have lower levels of reproductive health due to poorer financial conditions and perpetual poverty in their generations, as well as a lack of access to reproductive health services. In Brazil, the fertility rate of blacks has also declined over time (21).

5.2. Social Determinants That Affect the Rate of Childbearing

5.2.1. Women's Empowerment Index in Society

A higher index of economic and socio-cultural empowerment increases childbearing (27).

5.2.2. Household Empowerment Index

A higher household empowerment index increases childbearing (18).

5.2.3. Women’s Education Level

A higher level of women's education reduces fertility (12, 13).

5.2.4. Husband's Level of Education

A higher level of education reduces childbearing (23, 27, 28).

5.2.5. Religion

Religion affects the level of access (23) and the use of family planning services, religious beliefs (17), and authority in decision-making, affecting childbearing (29). Various studies have associated Buddhism and Christianity with the highest rate of induced abortion (24, 30). However, in Burkina Faso, Islam and Christianity were associated with increased fertility (21). In Iran, childbearing is more common among the Sunni population (21).

5.2.6. Index and Degree of Women's Authority in Making Decisions About Reproductive Health and Childbearing

Increasing women's authority and autonomy in various aspects of decision-making, such as fertility and childbearing, disagreement with couples in decision making, and less age gap between couples with reduced pregnancy in adolescence, reduce childbearing (14, 15, 31).

5.2.7. Index and Degree of Family Authority in Decision-Making About Childbearing

Increasing the authority index in family decision-making leads to a decrease in childbearing (25).

5.2.8. Minimum age at First Marriage, Sexual Activity, or the Birth of the First Child in the Community

A lower age at which a woman gets married, starts having sex or gives birth to the first child leads to higher childbearing rates in that population.

5.2.9. The Rate of use of Mass Media and the Rate of Receiving Reproductive Health Education and Family Planning Messages from Mass Media

Increasing the overall rate of mass media use or receiving family planning messages reduces childbearing (24, 27).

5.2.10. Micro and Macroeconomic Determinants

A low level of national income (26), low socioeconomic class, poor socioeconomic situation of the province of residence, an increase of household expenditure, an increase of per capita cost of education, an increase of average cost or rent of housing in residential areas, reduce fertility. In some societies, a lower wealth quintile has led to a decrease in fertility by increasing unsafe abortions and compromising reproductive health (30). On the other hand, the lowest quintile welfare in some communities, due to a 40% reduction in the possibility of using long-term contraceptive methods and access to family planning services, had more children (13). However, in other societies, the poor had fewer children due to more use of contraceptive methods (19). Paradoxical effects require specific studies for each region and community.

5.2.11. Average Ideal Number of Children in the Community and the Place of Residence

The higher the ideal number of children and desired size of the family in the norm of society, the higher the childbearing rate in that society (19, 25, 27).

5.2.12. Status and Employment Rate of Women

In working women and societies that have a higher average of women's employment, childbearing decreases (24, 26).

5.2.13. Status, Class, and Employment Rate of Men

Unemployment or a lower occupational class or employment rate in men reduces childbearing. However, another study showed that unemployment in the family increases the rate of adolescent pregnancy (22).

Different employment conditions can have varying effects on reproductive health and the level of expenditures, which should be carefully and separately examined in different communities.

5.2.14. Child Sex Preference and the Number of Children in the Family

Child sex preference and the number of children in the family, as well as the decision of the family to have children in the future, have been shown to affect childbearing rates. Studies indicate that when the number of children in the family reaches 2 or 3, childbearing decreases (19, 31). Additionally, having a son in the family reduces the likelihood of further childbearing (19). However, couples who have a decision to have children in the future and do not plan to have them at the moment may intermittently use contraceptive methods, resulting in a decrease in childbearing (13).

5.2.15. Women's Age

Women's age is a crucial factor that affects reproductive health outcomes. The highest rate of contraceptive method use is observed in the age group of 25 to 35 years (19). However, the rate of long-term contraceptive method use among this age group is lower (13), and the rate of induced abortion or termination of pregnancy is higher among older women, particularly those over the age of 35 (24). The highest rates of pregnancy and premature birth occur between the ages of 18 and 19 (15). Women's decision-making authority about pregnancy is lowest in the age group of 15 to 19 (29). Women in the age group of 10 to 19 have the least access to reproductive health services and prenatal care (32). Therefore, this age group is one of the most vulnerable in terms of reproductive health and requires targeted interventions.

5.2.16. Indigenousness or Immigration

Indigenousness or immigration can affect reproductive health outcomes. Migration can lead to numerous discriminations and deprivations for the immigrant population, with reproductive health, such as early marriage, early sexual activity, and unintended pregnancy, being more prevalent among immigrants (26, 33). However, as immigrant generations advance, such as the children and grandchildren of early immigrants, these inequalities decrease, and the reproductive health status improves (33).

5.2.17. Residence

Residence, i.e., urban or rural, can also affect reproductive health outcomes. Urban life, despite better access to reproductive health services (34) and greater women's authority in making reproductive health decisions (29), may lead to lower fertility rates due to the increased use of contraceptive methods (35) and intentional termination of pregnancy (26). Total fertility rates are higher in rural areas (12).

5.2.18. The Marital Status of Women

The marital status of women is also associated with increased fertility in more favorable and healthier conditions (24).

As mentioned, social determinants can increase inequality in the use and access to reproductive health services, family planning, and prenatal care, leading to disparities in reproductive health outcomes and optimal childbearing of women. Although some inequalities in access to services, such as those between rural and urban areas or different levels of family income, have decreased over time due to local health system interventions, rural-urban inequalities in fertility rates and among different income groups persist (35). Racial-ethnic-national discrimination has also been identified as an important factor of inequality in reproductive health. The issue of racial discrimination, especially as it pertains to minorities, is rooted in slavery. Black slave women were sexually abused to provide more economic benefits to their masters by giving birth to more slaves. Still, the fertility rate of blacks has steadily declined over time (11). Racism in its various aspects, such as structural racism, interpersonal racism, and racism in midwifery, perpetuates health disparities. More employment of women in providing services without controlling racist beliefs and cultures, disproportionate distribution of forces in urban and rural areas, and racial incompatibility of the workforce providing health services with residents of areas, especially rural areas, are among the reasons for not reducing health inequalities (36). The issue of minorities can also be considered from other perspectives in some countries, as membership in certain groups or tribes or belief in a particular religion can lead to the unjustified superiority of one group over others and exacerbate health inequalities (29). Cultural and belief differences must be taken into account.

Another important component that affects childbearing rates is the economic determinant, which can have an impact at the micro and macro levels. Factors such as maternity costs and related services should also be considered; as the average cost of these services increases, families desire to have more children, and childbearing decreases (37). Inadequate access to healthcare facilities due to long distances from the place of residence to health service providers is another important reason for reduced access and, consequently, reduced reproductive health (17). Some areas experience lower access to health services, leading to increased inequality and reduced reproductive health (17). Road problems, lack of transportation facilities, and lack of security, despite the lack of significant distance from service centers, are also important barriers to accessing health services and lead to increased inequality and reduced reproductive health in some areas (17, 36).

In addition to all of the above, non-health sector factors play a crucial role in reducing inequality in reproductive health. Policies developed to govern the country must be reviewed and adjusted for their effects on population health conditions. “Health in All Policies” is a critical issue that is a main pillar of community health promotion interventions. Local policymakers must address inequalities in health in their region by developing innovative and localized policies (38).

5.3. Limitations in the Study

(1) The scope of this study was restricted to articles published between 2010 and 2019 due to the extensive volume of data available.

(2) Articles that were written in languages other than English or Persian were excluded from the review.

(3) A few extracted articles could not be accessed in their entirety or abstract form and, therefore, were excluded from the study.

5.4. Study Strengths

This study has a distinctive approach in which all facets of women's reproductive health and childbearing, along with the social determinants that influence them, were comprehensively examined.

5.5. Conclusions

To promote women's reproductive health and childbearing, it is necessary to consider the social determinants that indirectly and significantly impact their health, as with other health aspects. Various studies worldwide have identified the most important social determinants that affect reproductive health and childbearing, including racial-ethnic-national discrimination (in the case of immigrants, racial and religious minorities), micro- and macro-economic factors (household welfare index, average family income, national income level, costs of living and education, costs of reproductive and obstetric health services), socio-cultural determinants (level of education, employment, socio-economic-cultural class of the family, socio-cultural norms such as the ideal number of children in the family, child sex preference, common age for marriage and sex, and marital status), and socio-geographical factors (country, province and region of residence, and urban status).

In the formulation of health-oriented policies across the country, special attention should be given to these determinants.