1. Background

Hookah is an ancient means of tobacco smoking across the world that dates back to the 16th century in India. It was later introduced in Iran, Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean region. After becoming common in Iran, hookah was gradually transformed into its present shape (1, 2). Hookah smoking spread gradually across Europe and the US in the last two centuries and has become increasingly common throughout the world, especially in Europe and North America (3). The main causes of the increase in the prevalence of hookah smoking include the spread of flavored tobacco, the false belief that hookah has less health risks than cigarette, attractions for youth, the increased presence of hookah in public places such as teahouses and the lack of efficient control policies (4). One session of hookah smoking often lasts longer than it takes to smoke a single cigarette; as a result, more smoke is inhaled when smoking hookah. One full session of hookah smoking is associated with inhalation of 100 times more toxic substances than is inhaled by each cigarette smoked (5). Moreover, the smoke inhaled through the hookah also contains carcinogens and other toxic substances and metals found in the smoke of cigarette (6).

Regarding the evidence on nicotine addiction with hookah smoking, hookah can be considered to cause similar diseases as cigarette (6-8). In the Eastern Mediterranean region, hookah is often smoked recreationally and has its own rules and customs. Hookah smoking was incorporated into the culture and tradition of societies over time and most hookah smokers are comprised of old individuals and retired men (9). Advertisements on hookah smoking began in 1990 and involved the introduction of flavored varieties of tobacco and their modern trading and distribution networks in different societies; these advertisements were partly responsible for the spread of hookah among different groups, including youth (10-13).

The increased prevalence of hookah smoking is not the only matter of concern; the characteristics of hookah smokers have also changed over the years and should be further examined. Studies in the Mediterranean region show an increase in the prevalence of hookah smoking among adolescents and younger adults (1). One study reported the prevalence of hookah smoking as 17% in the 18 to 29 year-old age group (8). Al-Lawati (14) reported the prevalence of hookah smoking as 9.6% among adolescents aged 13 to 16 in Oman.

In Iran, Sabahy et al. (15) reported that 42.5% of the university students were examined to have experience of smoking hookah and 18.7% of them to have smoked hookah in the past 30 days.

Hookah smoking is associated with specific behaviors and distinct sights in teahouses and traditional restaurants (16). Fruit-flavored tobacco or sweet varieties have attracted the youth to this tobacco product instead of cigarettes (17).

Its various methods of serving, the different places that serve it, the company that one can choose to share a hookah with, the serving of beverages alongside hookah and the easy access to hookah and charcoal have given hookah smoking a specific culture that contributes to its popularity.

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted to examine the characteristics of Iranian hookah smokers. The findings of the present study can help promote public health, especially considering the increased prevalence of hookah smoking across the world, including in the Eastern Mediterranean region and Iran.

3. Methods

The present cross-sectional study examined hookah smokers aged 15 and above residing in Tehran. The participants were selected from five random districts of the municipality of Tehran through multistage cluster sampling based on the population distribution within districts.

Tehran consists of five different geographical regions (i.e. northern, southern, eastern, western and central Tehran) and 22 municipal districts, each boasting several more zones. One municipal district was randomly selected from each geographical region of the city, including District 1 from northern Tehran, district 20 from southern Tehran, district 21 from western Tehran, district 14 from eastern Tehran and district 12 from central Tehran. Two zones were then randomly selected within each district, each of which had one health center with several health workers. Each of the health care centers covered a number of families within that zone. One family was randomly chosen by their address and all the neighboring families were then examined in a clockwise direction. Data collection was carried out by the health workers at the selected healthcare centers and under the supervision of a member of the tobacco prevention and control research center. The study had five different data collection teams, with each team consisting of one supervisor and two interviewers. The interviewers were selected from health workers working at the select centers and based on their research and volunteer experiences. After informing the data collection team about the objectives of the research project, they received training on data collection. The interviewers visited the selected households, presented their identification cards, and upon explaining the objectives of the research and obtaining their verbal consent, interviewed everyone aged 15 and above, in each household. All the eligible candidates were asked to fill out a questionnaire under the supervision of the interviewer.

The data collection tool used was the hookah section of the world health organization (WHO) (18) global adult tobacco survey (GATS). The GATS is part of the tobacco monitoring system for the over 15-year-old population in different countries. The first part of the survey covers participants’ demographic information. Once the demographic information was taken from all the participants with experience of smoking hookah, that is, all the participants who responded ‘yes’ to the question of “Have you ever smoked hookah?”, they were asked about their current smoking patterns. Only the participants, who smoked hookah every day or those who did not smoke everyday but had smoked hookah in the past 30 days were considered current hookah smokers (18). After identifying hookah smokers, the participants were requested to answer more specific questions of the survey regarding hookah smoking.

3.1. Measured Variables

Previous hookah smoking status: The previous status of smoking was examined by asking about the age at which the participant had smoked hookah for the first time, the company with whom and the place at which they had experienced their first smoke and their pattern of smoking in the past (daily or less than daily).

Current hookah smoking status: The current status of smoking was examined through questioning about the current pattern or frequency of smoking (daily or less than daily), the current place and the company with whom they smoked the number of hose tips used at each session and the type of tobacco used.

Attitude towards quitting hookah smoking: Participants’ attitude towards quitting was examined by asking whether they had taken any action to stop smoking in the past year, or whether they had decided to stop smoking within the past month or year or if they intended to stop hookah smoking at all.

Cigarette smoking status: Participants’ status of smoking cigarettes was examined by asking whether they had smoked cigarettes, their current smoking pattern and frequency, the number of cigarettes smoked per day and age at first cigarette use. After completing the data collection, the frequency of hookah smoking was statistically analyzed in the entire population and by gender.

The obtained data was analyzed using the SPSS-21 software. All the quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation while the qualitative variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). The student t-test was used to compare normal quantitative variables between the two groups and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used for the non-normal quantitative variables or for the ordinal qualitative variables. The Chi-square test was used to compare the nominal variables between the two groups and Fisher’s exact test was used only if necessary. The multivariate logistic regression was performed to estimate the odds ratio. All the statistical tests were two-tailed and were performed at a significance level of 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

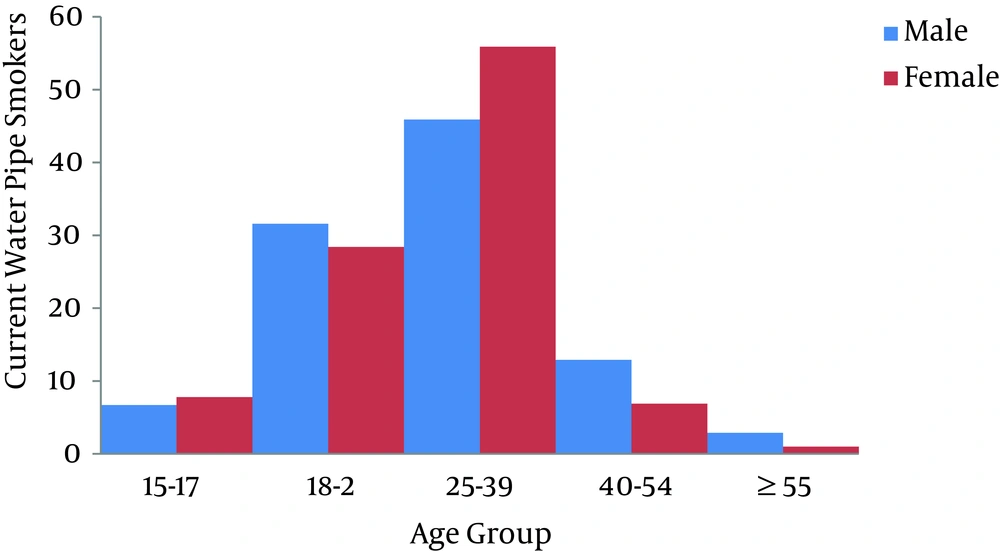

The present study examined 316 current hookah smokers, including 212 male and 104 female smokers. A total of 49.2% of the participants were aged 25-39; both genders had the same age distribution and the majority of the male and female hookah smokers pertained to this age group. There were no significant differences between the two genders in terms of age. Figure 1 shows the age distribution of hookah smokers. The majority of the smokers in both genders had a high school diploma, while, most of the participants with university degrees were female (42.7% female vs. 25.1% male participants with university degrees). The majority of the male and female participants were married, but the number of single male smokers was higher than the number of single female smokers.

4.2. History of Hookah Smoking

Home was the place where most of the participants had started smoking hookah for the first time (21.2% had started smoking for the first time at home and 22.5% at a party) and traditional restaurants and parks were the other main places where the participants had started smoking for the first time. The majority of the female smokers had started smoking hookah for the first time in traditional restaurants or at their home; however, the majority of the male smokers had started smoking hookah for the first time in parks (24.5%), (Table 1). The majority of the participants had smoked hookah less frequently than daily in the past. A history of daily hookah smoking was more prevalent among male (51.9%) than female (35.9%) participants. The mean age at first hookah smoking was 21.3±6.3 in the population as a whole; however, it was higher in the female (21.97 ± 5.8) than in the male (20.96 ± 6.6) participants (P = 0.02).

| Characteristics | Male | Female | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of education | 0.001 | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (2.4) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (2.5) | |

| Below high school diploma | 73 (34.6) | 17 (16.5) | 90 (28.7) | |

| High school diploma | 80 (37.9) | 39 (37.9) | 119 (37.9) | |

| University degree | 53 (25.1) | 44 (42.7) | 97 (30.9) | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | |||

| Married | 105 (50) | 57 (55.9) | 162 (51.9) | |

| Single | 104 (49.5) | 37 (36.3) | 161 (45.2) | |

| Widowed | 1 (0.5) | 8 (7.8) | 9 (2.9) | |

| Previous hookah smoking status | 0.009 | |||

| > 3 - 4 times within months | 151 (71.6) | 56 (54.9) | 207 (66.1) | |

| 1 - 2 times within one months | 35 (16.6) | 35 (34.3) | 70 (22.4) | |

| 1 - 2 times within 2-3 months | 105 (50) | 57 (55.9) | 162 (51.9) | |

| Once within 6 - 12 months | 105 (50) | 57 (55.9) | 162 (51.9) | |

| With whom did you start smoking hookah? | < 0.001 | |||

| Parents | 16 (7.5) | 9 (8.6) | 25 (7.9) | |

| Friends | 161 (75.9) | 54 (51.9) | 215 (68) | |

| Siblings | 10 (4.7) | 9 (8.7) | 19 (6) | |

| Alone | 12 (5.7) | 5 (4.8) | 17 (5.4) | |

| Others | 13 (6.2) | 27 (26) | 40 (12.7) | |

| Where did you smoke your first hookah? | < 0.001 | |||

| At a coffee shop | 41 (19.4) | 8 (7.7) | 49 (15.5) | |

| In the Park | 52 (24.5) | 9 (8.6) | 61 (19.3) | |

| At a traditional restaurant | 35 (16.5) | 27 (25.9) | 62 (19.6) | |

| At home | 38 (17.9) | 29 (28) | 67 (21.2) | |

| At a party | 41 (19.3) | 30 (28.8) | 71 (22.5) | |

| Other | 5 (2.4) | 1 (1) | 6 (1.9) | |

| Where do you usually smoke hookah? | < 0.001 | |||

| At coffee shops | 50 (23.7) | 3 (2.9) | 53 (16.8) | |

| At home | 94 (44.5) | 74 (71.2) | 168 (53.3) | |

| In parks | 50 (23.7) | 11 (10.6) | 61 (19.4) | |

| At traditional restaurants | 17 (8.1) | 16 (15.3) | 33 (10.5) | |

| How many bowls do you use in every hookah session? | 0.17 | |||

| 1 | 129(63.5) | 72 (72) | 201 (66.3) | |

| 2 - 3 | 62(30.5) | 22 (22) | 84 (27.8) | |

| More than 3 | 12(6) | 6 (6) | 18 (5.9) | |

| How many hookah bowls did you finish last time you smoked? | 0.025 | |||

| 1 | 111 (52.4) | 65 (62.5) | 176 (55.7) | |

| 2 | 60 (28.3) | 32 (30.8) | 92 (29.1) | |

| 3 | 26 (12.3) | 3 (2.9) | 29 (9.2) | |

| 4 | 15 (7) | 4 (3.8) | 19 (6) | |

| Where did you have your last hookah smoke? | < 0.001 | |||

| At home | 85 (40.1) | 61 (59.6) | 146 (46.6) | |

| At a coffee shop | 57 (27.2) | 8 (7.7) | 65 (20.7) | |

| In a restaurant | 22 (10.4) | 20 (19.2) | 42 (13.6) | |

| In the park | 34 (16.1) | 11 (10.6) | 45 (14.6) | |

| Other | 11 (5.2) | 3 (2.9) | 14 (4.5) | |

| How often do you smoke cigarettes right now | < 0.001 | |||

| Daily | 66 (44.6) | 9 (15) | 75 (36) | |

| Less than daily | 29 (19.6) | 16 (26.6) | 45 (21.7) | |

| Never | 53 (35.8) | 35 (58.4) | 88 (42.3) |

A significant percentage of the participants (68%) began smoking hookah in the company of their friends (51.9% of the female vs. 75.9% of the male participants); (Table 1).

4.3. Current Status of Hookah Smoking

A large number of participants smoked hookah more than three to four times per month (54.9% of the female vs. 71.6% of the male smokers). The majority of the participants currently smoked hookah less frequently than daily (67.4%); however, a greater percentage of the male participants smoked hookah daily when compared to female participants (37.7% vs. 22.1%) (P = 0.005). Both genders smoked hookah mostly at home (71.2% of the female vs. 44.5% of the male smokers). Traditional restaurants were the next most common place for the male participants to smoke hookah (15.4%), followed by teahouses (23.7%) and parks. The majority of both male and female participants finished only one hookah bowl of Shisha each session (72% of the female vs. 63.5% of the male participants). The mean daily frequency of hookah smoking was 1.37 ± 0.71 times in the female and 1.48 ± 0.87 times in the male participants (P = 0.47).

The mean weekly frequency of hookah smoking was 4.96 ± 4.99 times in the male and 3.57 ± 2.59 times in the female participants (P < 0.001). The mean number of people sharing one hookah was 2.92 ± 1.62 for the male and 2.73 ± 1.48 for the female participants (P = 0.49). The majority of both the male and female participants smoked flavored tobacco (91.3% of the female and 83.8% of the male participants).

4.4. Attitude Towards Quitting Hookah Smoking

About 30.8% of the female and 35.7% of the male participants had actively tried to quit smoking hookah in the past year. The maximum duration of their abstinence from smoking was not longer than a few weeks.

About 22.2% of the female and 20.6% of the male participants stated that they meant to quit smoking hookah within the next month. About 22.2% of the female and 18.2% of the male participants considered quitting smoking hookah within the next year; however, a significant percentage of the participants, that is, 55.6% of the female and 61.2% of the male participants, did not intend to quit smoking hookah at all.

4.5. Cigarette Smoking

A significant number of the participants smoked cigarettes; however, the experience of smoking cigarettes was more common in the male than in the female participants (60.5% vs. 43.6%); (P = 0.005). Overall, 38.6% of the participants did not smoke cigarettes at the time of the interview, while 32.9% smoked cigarettes every day. A total of 41.5% of the male and 13% of the female participants smoked cigarettes every day. Nevertheless, 50.7% of the female and 33.3% of the male participants did not smoke cigarettes at all (P < 0.001).

The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day was 5.7 ± 6.5 in the male and 2.6 ± 4.08 in the female participants. The mean age at first cigarette smoking was 23.7 ± 60.06 in the female and 22.8 ± 6.5 in the male participants. A total of 50% of the female and 38.8% of the male participants smoked their first cigarette of the day one hour after getting up.

4.6. Multivariate Correlates of Daily Hookah Smoking

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were used to evaluate the association between selected variables and daily Hookah smoking. The variables were age, initiating age of Hookah smoking and current usual palace of Hookah smoking, which was categorized to two groups at home and outdoor use (coffee shop, restaurant, traditional restaurant and park). The results are shown in Table 2. In multivariate analysis being male and Hookah smoking at home compared to outdoor Hookah smoking were significantly associated with daily Hookah smoking (OR 2.29 (95%CI 1.3 - 4) and OR 2.18 (95%CI 1.3 - 3.6), respectively).

| Variable | Crude OR | Adj OR | 95%CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 1.88 | 2.29 | 1.3-4 | 0.004 |

| Usual place of Hookah smoking (at home/outdoor) | 1.75 | 2.18 | 1.3-3.6 | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.1 | 1.13 | 0.8-1.6 | 0.4 |

| Initiation age of hookah smoking | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.9-1 | 0.2 |

5. Discussion

The present study examined the characteristics of hookah smokers aged 15 and above and compared them by gender. Given the spread of hookah smoking among the Iranian population and especially the changes in smoking patterns and smokers’ characteristics, the present study was conducted to identify the characteristics of hookah smokers in Iran and to present information on the subject.

A total of 212 male and 104 female participants were examined in terms of their smoking characteristics. The majority of hookah smokers from both genders were aged 25 to 39 years old; that is, they were young adults. Most participants had high school diploma and university degrees. Compared to the male smokers, a higher percentage of the female smokers had university degrees. In the study conducted by Baheiraei et al. (19) on female smokers, the majority of hookah smokers were aged 15 to 24 years and hookah smoking was more prevalent in women with bachelor’s degrees or higher than in women with only a high school diploma.

The results obtained on participants’ age distribution were consistent with the results obtained in different foreign studies, especially with those in the Eastern Mediterranean region. In line with the present study’s findings, indicating that most hookah smokers are young adults, studies conducted in Syria, Lebanon and other Middle Eastern countries also revealed an alarming increase in hookah smoking among adolescents and young adults (8).

In the study by Primack et al. (20), most hookah smokers were aged 18 to 24 years old. The age distribution of hookah smokers in Lebanon showed that about 30% of this group comprised of young adults (21). An epidemiologic study conducted in Syria (8) showed that 15.7% of hookah smokers were aged 18 to 29 and that 12.1% were aged 30 to 45.

Hookah smoking is more prevalent among the educated individuals, who maybe said to have begun smoking hookah under the misperception that smoking hookah is harmless or of little harm (10, 22). In the study of Ward et al. (23), most hookah smokers had academic education. It seems that educated individuals tend to care more about their health; a stronger misperception appears to exist among them about the safety of smoking hookah compared to smoking cigarettes. A significant percentage of the study population smoked hookah daily (38% of the male and 22% of the female participants, and 32.6% of the entire population). The present study obtained a higher frequency of daily hookah smoking compared to similar studies conducted on the subject. This frequency of daily smoking was higher than that of similar studies. Ward et al. (23) found that 13% of the population in one city of the US and 3% of the population in another city smoked hookah daily. About 11% of the male and 2% of the female population in Vietnam, 5.5% of the male and 3% of the female population in Egypt and 3% of the male and 0.0% of the female population in Turkey smoke hookah daily (24). Mohammadpoorasl et al. (25) conducted a study in Tabriz, Iran, and revealed that 85% of the participants smoked hookah daily. It should be noted, however, that their study was conducted on individuals frequently attending teahouses, while the present study was conducted on the general public. In a study conducted in Syria, 1.4% of the male and 0.6% of the female population smoked hookah daily (8).

A significant percentage of the study population stated that their first hookah experience was in the company of their friends, which is consistent with the results obtained by many other studies regarding the social aspect of hookah smoking. In the study by Maziak et al. (17), both the male and the female participants had started smoking hookah in the company of friends. A qualitative study conducted by Hammal et al. (26) also found that participants’ first hookah experience was initiated by friends and in public places.

The majority of the participants in the present study had started smoking hookah at their own or their friends’ home. Nevertheless, compared to female smokers, a higher percentage of male smokers had begun smoking hookah in parks. Traditional restaurants were one of the more common places where female smokers had begun smoking hookah. These findings can be attributed to gender differences inherent in the Iranian culture, where smoking in public is a taboo for women, and women therefore do not tend to smoke hookah in parks. Nevertheless, the increased number of traditional restaurants serving hookah has fulfilled women’s need for smoking hookah outside their home and has thus highlighted the recreational dimension of hookah smoking for this group of smokers.A significant percentage of male and female participants in this study smoked hookah at home, but male’s desire to smoke hookah at parks was higher than that of females, who preferred to smoke hookah at traditional restaurants.

One of the changes in the characteristics of hookah smokers is the desire to smoke individually at home. Although the collective and social aspect of hookah smoking used to be more striking, studies show that addiction to hookah has changed the smoking pattern from collective to individual smoking, as currently more people tend to smoke at home (27). According to the results of this study, smoking hookah at home significantly correlated with daily smoking. People smoking hookah at home seem to have a personal hookah. It could be hypothesized that ownership of Hookah leads to easy access and increases frequency of use. Some studies show the correlation of possession of a personal hookah with daily smoking and increased frequency of smoking. Furthermore, a reason for increased hookah smoking is the spread of teahouse culture. The number of teahouses in different parts of cities in Iran has increased in the recent years based on economical and social conditions. There are teahouses in Tehran fulfilling the needs of customers from different classes of the society. In other words, modern teahouses with higher costs have been developed along with old traditional teahouses. Most people, especially young adults, spend their free time in such places. Those teahouses serve all kinds of beverages and even foods. Therefore, many people begin smoking hookah there, and the risk of regular daily smoking increases.

The mean age at first hookah smoking was 21.3 ± 6.4 in the present study. In the study by Ward et al. (23), most participants began smoking hookah in their early 20s; however, 47% of the smokers in one of the investigated cities began smoking hookah after the age of 21. Morton et al. (24) demonstrated that, in Egypt, Ukraine and Vietnam, a large number of men began smoking hookah before the age of 25, while in Turkey, more people began smoking hookah after the age of 25.

A significant number of participants in the present study smoked flavored tobacco. The availability of fruit-flavored tobacco in the market may itself be one of the reasons for the increased prevalence of hookah smoking. Various studies confirm these findings (10-13).

A few participants (37%) stated that they had taken steps to quit smoking hookah and a few had quit smoking for a few months. However, a large number of participants did not intend to quit smoking at all. This confession may show their addiction to hookah, on the one hand, and their misperception of how addictive hookah can actually be, on the other. They may think that it is easy to quit smoking hookah and that they can do so whenever they desire. Moreover, they are not motivated enough to quit smoking hookah because many hookah smokers, whether in Western countries or in the Middle East, believe that hookah is much less addictive than cigarette and do not consider themselves addicted to hookah (4, 7, 17).

A large number of the participants had smoked cigarettes and 33% of them smoked cigarettes on a daily basis at the time of the interview. A larger percentage of males smoked cigarettes on a daily basis. One of the significant features of hookah smoking is that it encourages the smoker to smoke cigarettes as well. Given adolescents’ high tendency towards hookah smoking, they appear to be the target of cigarette addiction as well. According to a number of studies, the first type of tobacco used was hookah tobacco. Some people find hookah a good alternative to cigarettes after quitting smoking the latter. In the study by Ward et al. (23), 79% of the participants had smoked at least one cigarette in the past month, and 59% of the participants in one of the examined cities confessed that they would definitely smoke cigarettes within the next year, although they did not smoke cigarettes at the moment. A certain number of young adults smoking hookah have never smoked cigarettes, which indicates that millions of youth are exposed to tobacco smoke through the hookah and then become addicted to nicotine (6).

Many studies reveal a significant correlation between hookah and cigarette smoking; however, there is not enough evidence about the predictive power of cigarette smoking in determining the tendency to hookah among youth (27, 28).

The present study was the first to examine the characteristics of current hookah smokers in Iran. Since the study participants were selected from all the districts and regions of Tehran through cluster sampling, the results obtained can provide comprehensive data on the characteristics of hookah smokers in Iran.

5.1. Limitations

Despite the geographical distribution of the samples, the sample size was not adequately large; conducting further studies with larger sample sizes is therefore crucial. The present study was conducted on hookah smokers aged 15 and above and the results cannot be generalized to younger smokers.

5.2. Conclusion

Hookah smokers in Tehran are mostly comprised of young adults. The majority is educated and has at least a high school diploma. They often begin smoking hookah in the company of their friends, while their first hookah experience tends to take place at home. Home and teahouses are currently the most commonplaces where this group of the population smokes hookah. Smoking at home increases the rate of daily smoking. Female hookah smokers tend to smoke hookah in traditional restaurants while male smokers tend to smoke hookah in parks and teahouses. Most hookah smokers prefer flavored (especially fruit-flavored) tobacco. Most of the smokers do not currently plan to quit smoking hookah. The majority has smoked cigarettes in the past and one-third smokes cigarettes. A larger percentage of male hookah smokers smoke cigarettes on a daily basis compared to female hookah smokers.