1. Background

Pricing of health services is influenced by technical and political considerations along with certain contextual factors. The market failure in the health sector and nformation asymmetry between caregivers and patients force the government to look for appropriate policies (1). In some countries, the government is the absolute player in setting the care charges. In other countries the diagnostic related groups (DRG) is the main payment mechanism for private and public sectors (2-4).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) in United States of America (5) has used the RVUs as a reimbursing tool for physicians since 1992. They RVUs were defined based on 5 factors including (6, 7):

- Time spending

- Complication of service

- Provider’s technical and mental involvement

- The overhead facilities to provide service, and

- The level of risk related to service for patients

These factors are placed in 3 components of i, physician’s work; ii, expenses of medical services provision; and iii, mal-practice probability. These components are adjusted by the geographic practice cost indices (GPCI). If the RVUs are multiplied by monetary value called conversion factor (CF), the fee for each service is defined (8, 9).

The previous system of valuing the health services in Iran is adopted from the Californian RVUs. Hence, determination of health care tariffs has been a heated debate among main stakeholders, which often reached a consensus through political processes rather than technical (10).

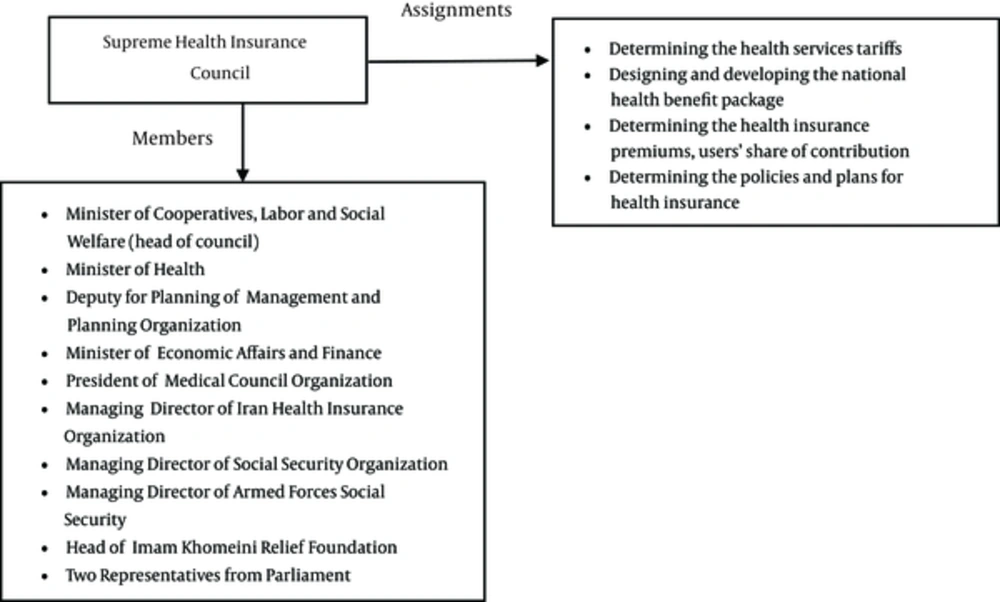

An authority called “supreme health insurance council” (SHIC), whose members are from different regulatory and payer organization, is responsible for approving the health tariffs. Nonetheless, the providers believed their services were not valued on the basis of the economic facts and therefore, demonstrated their dissatisfaction on and on. They tried to compensate the gap between approved tariffs with the so-called “real tariffs” through the informal payments or induced demand (11, 12).

For more than 3 decades, the out of pocket payment was the main source of health care financing in the country (10). However, after implementing the health transformation plan -2014- the government tried to revise the relative value units in Iran after 30 years.

But due to the fact that the physicians’ and providers organizations’ pressure the MoH, it was decided to revise the Californian RVUs (13).

The goals were to set real monetary values for health services, reduce the inequality between medical practitioners’ earnings, reduce the informal payments, value the new procedures, services, interventions as well as cares, and revitalize the medical fields such as infectious diseases specialists, internal medicines, and pediatrics that did not have much financial attraction for the medical students.

The RVUs revisions included considerable changes in the related values. A sample of revised codes is compared with their old versions in Table 1.

| Californian RVUs | New RVUs | Growth Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitions | RVU code | Definitions | RVU code | |

| Canthoplasty (reconstruction of canthus ) | 12 | Canthoplasty (reconstruction of canthus ) | 26 | 116 |

| Pars plana vitrectomy with/without refractive lens exchange | 35 | Pars plana vitrectomy | 60 | 71.4 |

| Saphenopopliteal vein anastomosis | 20 | Saphenopopliteal vein anastomosis | 55.2 | 176 |

| Cutaneous vesicostomy | 18 | cutaneous vesicostomy | 35.4 | 92.2 |

| Closure cystostomy | 8 | Cystostomy, cystostomy with drainage, closure cystostomy | 15.2 | 90 |

| Cystostosomy with driange | 12 | |||

| urethrotomy through bladder | 22 | Urethrotomy through bladder | 28.2 | 28.2 |

| Ulnar osteotomy | 10.3 | Radius or ulnar osteotomy | 42 | 307.7 |

| Radius osteotomy | 10.3 | 307.7 | ||

| Tibial osteotomy | 12.5 | Tibial osteotomy or fibular tibial and fibular | 24.8 | 98.4 |

| Fibular osteotomy | 6.5 | 282 | ||

| Complete or partial salpingectomy unilateral or bilateral | 10.4 | Salpingectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy, complete or partial, unilateral or bilateral | 30 | 188.5 |

| Complete or partial salpingo-oophorectomy unilateral or bilateral | 11.4 | 163 | ||

| Radical prostatectomy | 26 | Radical perineal prostatectomy | 65.4 | 151.5 |

| Epiglottidectomy | 16 | Epiglottidectomy | 42 | 162.5 |

| Total splenectomy | 16 | Partial or total splenectomy or repair procedures on the spleen | 46 | 187.5 |

| Partial splenectomy | 20 | 130 | ||

| Repair procedures on the spleen | 15.5 | 196.7 | ||

Regarding to the changes in RVUs, we aimed to identify the pitfalls of the new version of fees schedule based on the localized RVUs (second edition) in Iran from the perspective of providers in 2016.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

In the time of conducting the study, there were 163 approved medical associations and societies by the MoH, which 34 associations and societies were invited and involved in revising process of the national RVUs. Therefore, a purposeful two-stage sampling was used to collect the data. Firstly, 34 scientific medical associations and societies were selected, then, a sample of 54 members was included until we reached information saturation about the difficulties and pitfalls of the revision. The inclusion criteria for participants were either of: i, being introduced and approved by the correspondent associate/society; ii, having good information about the RVUs, based on their own statements; or iii, having research in the field of RVUs. A list of interviewees has been presented in supplementary file Appendix 1. A total of 54 face-to-face interviews (that 20 of them were done through telephone) interviews were accomplished. The time of interviews ranged from 36 minutes to 65 minutes with an average of 49 minutes. All the interviews were accomplished on July 2016 to September 2016 by H.GH.

The interviews included 4 sections: a brief description of research, questions about the demographic characteristics, questions about participants’ level of satisfaction with the current version of Iranian RVUs (second edition), and finally the more deep questions about the new RVUs’ shortcomings. The ethics committee of research of study funder approved a consent form. The form has been read and signed by interviewees.

2.2. Data Analysis

An inductive content analysis based on the Elo and colleagues’ approach (14), included the 3 consecutive phases below:

- Preparation: all of the recorded interviews have been transcribed point by point.

- Organizing: the raw data has been coded to find common statements about the pitfalls

- Reporting: the relevant codes, themes, and categories based on the CMS framework and statements of the interviewees have been extracted.

3. Results

The demographic characteristics of interviews and then the main results have been presented in this section.

Most participants believed that the new version of RVUs had not worked well for resolving the existing problems. Their rationales for such views are categorized in 11 sub-themes and 7 themes, Table 2.

| Variable | Number (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 49 (91) | |

| Female | 5 (9) | |

| Educational level | ||

| MSc. and PhD. | 6 (11) | |

| Specialist | 32 (59) | |

| Fellowship | 8 (15) | |

| Subspecialist | 8 (15) | |

| Place of practice | ||

| Public | 19 (35) | |

| Private | 13 (24) | |

| Both | 22 (41) | |

| Age | 51 (12) |

| Variable | Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Pitfalls of new version of RVUs in Iran; raised by medical practitioners | Lack of clarity and transparency of the revision process | lack of convincing reasons about the logic of revisions |

| lack of an integrated and well documented report in this issue | ||

| inadequate communication with different medical associations/societies | ||

| Overcoming of political lobbying on technical considerations | Adopting a scientific and evidence-based process | |

| Negligence of the Evaluation and Management (E and M) section in the RVUs | The visits and consultations were not considered in the new version | |

| the valuing of visits and medical examinations is different from the RVUs in a partial way | ||

| MoH and health insurers’ weakness in regulating and controlling the providers | SHIC decided to merge different medical codes together | |

| MoH and health insurers’ insufficient knowledge for revision of the codes | The MoH and health insurers should enjoy the capacity of the associations/societies | |

| Lack of considering a transitional phase for implementation of the new RVUs | Lack of the in-filed studies and review of related experiences across other nations were not conducted | |

| Low level of flexibility about certain medical specialties and fields | Regulating everything may not be the best option. | |

| Physicians; level of expertise, experiences and skills of practitioners are not considered |

3.1. Lack of Clarity of the Revision Process

Lack of convincing reasons about the logic of revision

“The SHIC invited associations and discussed the content and values of each code, but I was not informed about the final result. I think all of our comments were almost excluded! (P.3).”

3.1.1. Overcoming of Political Lobbying on Technical Considerations

Determination of values in RVU schedule requires a scientific and evidence-based process. The participants believed that the political power of the associations/societies was the main determinant of RVUs.

“The SHIC’s officials said they wished to localize the American version of the RVUs. I think this was an excuse to revise the RVUs based on political power and will of certain medical groups or associations/societies! (P. 10).”

3.1.2. Negligence of the Evaluation and Management (E&M) Section

The visits and consultations were not considered in the new version of RVUs. Of course these sections were neglected in the old version as well, however, most experts expected them to be included in the new version.

“When I compare the chapters of our localized RVUs with the original version- the USA’s RVUs-, this makes me upset! As an internal specialist, I expect my services be considered in the RVUs (P. 5).”

The ignorance of the (E&M) section in the Iranian RVUs has led to another problem for physicians, due to the fact that now the valuing of visits and medical examinations is different from the RVUs.

“I am an experienced specialist with more than 20 years of practice in private sector. My patients are not similar regarding their status of illness and the frequency of referring to my office, but I should receive same amount from all of them! (P. 14).”

3.1.3. Weakness in Regulating and Controlling the Providers

The MoH and payers are not able to deal with informal payments and over-charged bills. Hence in new localized RVUs, the SHIC decided to merge different medical codes together and then calculate their related values through averaging.

“If the MoH and SHIC are not going to develop a strict regulating mechanism, why did they revise the RVUs? Without a controlling system the new RVUs are useless (P. 31).”

3.1.4. MoH and Health Insurers’ Insufficient Knowledge

The MoH and health insurers should have enjoyed medical groups’ knowledge and experiences in revising the codes. The MoH and SHIC developed a simplified version of RVUs rather than a localized one.

“The MoH and SHIC involved themselves in a pure technical action in RVUs, which they did not have detailed knowledge in. The explanations of codes and valuing them are specific work expected to be accomplished by medical groups or associations/societies (P. 24)”.

3.1.5. Lack of Considering a Transitional Phase for Implementation

The MoH should have undertaken adequate studies to prepare the field through a transitional phase. The in-filed studies and review of related experiences across other nations were not conducted. The MoH is now facing unpredicted consequences.

“The SHIC started the revisions, without a detailed and comprehensive investigation of the contemporary situation. The Board of Ministers approved the first draft of the revised RVUs within a few months after starting the revision and there were many sources of pressure on the MoH to establish the announced changes (P. 50).”

3.1.6. Low Level of Flexibility about Certain Medical Specialties and Fields

The new version of RVUs includes different criteria for calculating the value of all services. However, level of expertise, experiences, and skills of practitioners are not considered.

“As a nation-wide well-known surgeon, I am a brand and I am a distinguished one but in terms of the RVUs, I am regarded as the same with an inexperienced and new graduated surgeon! (P. 44).”

4. Discussion

Over the past 3 decades, the Californian RVUs were the common tool for determining the fee schedules in Iran (2). Most of participants believed that the new version (second edition of new version) of RVUs had serious challenges for the Iranian health system.

The participants concerned the low clarity and transparency of revising process and unconvincing rationales. All of the revisions, their roots, and the outcomes should be documented and available for the main stakeholders. This can make an atmosphere of trust among most stakeholders. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) makes such an atmosphere through the updating committee that receives comments from different parties and make them post it after drafting a new version (14). The SHIC should have obligated the technical aspects of valuing health services to multidisciplinary teams with more active contribution of medical associations/societies. The CMS agreed about 87% of changes offered by the committee and they emphasized on the importance of capacity building by CMS for strengthening of its abilities in analyzing the technical aspects of valuing the health services (14). Defining a logical process for adjusting the physicians’ fees has been highlighted by Ginsburg et al. (9).

Setting medical tariffs through the resource-based valuing mechanisms should be based on technical processes. However, the process involves certain political considerations caused by pressures of different stakeholders, especially medical groups.

A study in Iran shows that, one of the main dimensions for valuing the health services associates with the governance power. This highlights the role of political pressures of influential medical groups in determining the values of health services (15).

The role of political lobbying and need to manage its side effect on the revising or updating the physicians’ fee schedule as a challenging debate has been discussed by 2 previous studies in USA and Canada (16, 17).

Revising the physicians’ fee schedule is a long-time process, which needs a sufficient in-field study and should be accomplished through both transitional and implementation phases. This was concluded in a study in the USA (18). However, in Iran, due to the instability of managerial conditions, any government tries to accomplish the national plans in the shortest time and therefore, the feasibility studies are not usually performed. This was the case about the revision of the RVUs. The Iranian practitioners had adapted themselves with the Californian RVUs and then gradually, the equilibrium through the informal payments and induced-demand had been materialized. The CMS considers 2 mentioned phases including the transitional and implementation, the first usually comes some years earlier than the latter. The RAND Corporation conducted a study about the unification of CFs for all defined groups of practitioners in 2012 and the CMS decided to implement this through 2017 (19).

The Evaluation and Management are very important in diagnosing the diseases and laying out the effective treatment The Iranian health policy makers have implemented a simplified method to value the E and M services in out-patient settings through calculating the unit cost of provision of in-office visits and consultations, which is totally different from RVUs. A study concluded the shortcomings of RVUs in valuing of E and M and requirements of updating new topologies for these services (20).

In one study, the researchers have compared the numbers of the office visits and their completeness in the USA and Canada. They concluded that in Canada, this is more summarized, and depending on the state there are some limitations in reimbursing the physicians (17).

The considerable gap between the incomes of different groups of physicians is a historic problem in Iran. A study showed that the low level of values for non-invasive services lead to an inequitable distribution of income among medical groups (21).

Such a problem is not specific to Iran. In Japan, the current payment system led to an inequitable earnings. The researchers concluded that scopes of surgery and other medical activities should be separated and also, the difficulty and the efforts of manpower in providing the services should be modeled (22).

In Iran, the FFS payment mechanism can result in induced demand. Therefore, the state should develop appropriate controlling mechanisms (13, 23). Using the prospective reimbursement system is among current advice for reducing the financial burden of RVUs (24-26).

4.1. Conclusion

The logic behind any adjustment in the RVUs should be explained for medical groups so that there is no lack of clarity for such stakeholders about the changes. The issue of equity in RVUs, should be considered by involving different medical groups in the revision process. The demand side of the health market should be controlled by the in-charge bodies and by ruling out the traditional FFS payment and implementing prospective mechanisms. Finally, the MoH should consider designing the modifiers properly.

4.2. Limitations

Many of the participants did not eagerly show a tendency to speak about the advantages of the new version of RVUs.