1. Context

The importance of health has attracted the attention of many countries, driving them to strengthen the well-being of their citizens or transform such initiative into an industrial opportunity; correspondingly, competition in the health industry is currently promoted as a global phenomenon (1). In this regard, the features that advance the globalization of health include the presence of multinational hospitals, prices that are competitive across the world, international quality of global standards, and specialized technologies (2). One of the most important effects of the globalization of health is the emergence of a new form of tourism known as health tourism (3). Among health tourism sub-groups, medical tourism can be regarded as a product of the rapid growth of the health industry (1, 4, 5). Medical tourism is defined as the process in which patients travel to different countries to receive high-quality and suitably priced health care services (4, 6-8). It differs from health tourism in three ways: First, health tourism (health and wellness) services are provided in non-hospital settings, whereas medical tourism services are provided in hospital contexts. Second, in medical tourism, treatment is performed with medicines and surgical procedures, but in health tourism, intervention is implemented through complementary therapies for restoring health. Third, in medical tourism, patients are treated using the existing medical facilities in a hospital (9).

The efforts that some Asian countries, such as Thailand, Singapore, India, South Korea, and Malaysia, exert in promoting medical tourism has enabled them to successfully attract 1.3 million medical tourists from all over the world - a figure that continues to increase (10-12). In 2012, the health tourism sectors in India and Singapore earned $2 billion and $1 million in revenues, respectively (13). Given that the health market is currently a huge and well-developed industry, medical tourism earnings account for a significant proportion of world tourism revenues (14, 15). The health and medical tourism industries alone have been responsible for building a world trade market that is worth $60 billion and grows annually by 20% (16-18). For developing countries, both industries present excellent potential as a means of achieving considerable international earnings and employment with appropriate planning and implementation (19, 20). These industries therefore serve as sources of opportunity for all nations, regardless of developmental level (21).

The rising health care costs in most developed countries have increased the growth of medical tourism (22-24). Aside from increased costs, numerous other factors effectively render medical tourism a desirable option for patients who want to satisfy their health needs. Some of these factors are long waiting lists, high service costs, and lack of access to necessary services and high technology in home countries (6, 25-28). Given the tradability of health care, medical tourism is vulnerable to criticism, thereby encouraging destination countries to endeavor to provide health facilities and services with the highest possible standards to international patients (29, 30).

Features such as service providers (31, 32), medical facilities (33), the behavior of staff with patients (34), waiting time (35), and the quality of service and facilities (33, 36, 37) can affect the satisfaction of domestic and international medical tourists. Satisfaction can be regarded as an important aspect of quality and a key indicator of success in medical tourism. Patient satisfaction is important also because it increases competition among health service providers (38). The key role of satisfaction in the medical tourism industry is likewise reflected in people’s highly responsive practices for achieving their health goals and their demand for appropriate and high-quality services given advances in technology, increased awareness, and increased expectations from health service providers (39, 40).

Patient satisfaction can be analyzed particularly in combination with an examination of different hospital dimensions (41). The feedback that is gained with respect to patient satisfaction can also effectively guide efforts to improve a hospital’s status and strategic plans (42). Additionally, a survey of tourist satisfaction can clarify strengths and weaknesses as well as corrective measures for enhancing the satisfaction of medical tourists (23).

With consideration for the above-mentioned issues, this study was aimed at identifying the factors that affect the satisfaction of medical tourists. The research question pursued in this work was “What are the contributors to the satisfaction of medical tourists?”

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Objective

To identify the factors that affect the satisfaction of medical tourists, a systematic review was conducted between July 2016 and March 2017.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for the reviewed studies were original articles, case studies, reports, and theses that examined the factors affecting the satisfaction of medical tourists and that were published in Persian and English from 1990 onwards. We excluded abstracts presented at conferences, seminars, newsletters, and letters to editors.

2.3. Search Strategy and Data Source

For appropriate structuring of the systematic review, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (43). The search strategy was determined on the basis of guidelines from research experts. Studies published in both English and Persian were first searched in October and November 2016 over PubMed to ensure access to all relevant articles, after which English articles were searched from the databases of Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, ProQuest, Embase, and Ovid in accordance with a tailored strategy. Persian articles were searched over the Scientific Information Database and Magiran. Keywords that were extracted from the Medical Subject Headings were used for the searches. The specific keywords used were “medical tourist,” “health tourist,” “health tourism,” “medical tourism,” “satisfaction,” and “consent.” Equivalent words in Persian were also employed. The search was limited using the Boolean operators AND and OR. Some relevant journals, such as the Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, Tourism Management, and the International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing, and websites were searched manually. The reference lists of the selected articles were also checked. Finally, the gray literature was searched. The retrieved studies were imported into EndNote X7.4 and screened for inclusion in the final sample.

2.4. Data Extraction

In the first phase of the review process, we designed a data extraction table (Microsoft Word) that comprised the following items: first author’s name, year of publication, country, study design (method), sample size, and main results (determinants/factors). The validity of the data extraction table was confirmed by experts, and a pilot study (with two articles) was conducted for further improvement of the table.

Two of the researchers, who had enough experience and knowledge of data extraction, were responsible for independently extracting the data. Specifically, duplicate articles were eliminated, and titles and abstracts were independently screened. These investigators (M.H. and N.D.) also independently assessed relevant full-texts articles for eligibility on the basis of the predefined criteria. Any disagreements between the investigators were resolved through discussion with the third and fourth investigators (R.K.H. and M.Y.). The data on the influencing factors reported in each study were extracted and entered into the data extraction table.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The quality of the papers was examined independently by two of the researchers using the Kmet checklist (quantitative-qualitative) (44). The quantitative and qualitative features evaluated were research question, study design (whether evident and appropriate for answering the research question), methods (including data collection procedures), subject characteristics, randomization, blinding reported, risk of selection bias, sample size and sampling strategy, analysis, variance reported, control for confounding effects, results (whether reported in sufficient detail), results’ support of conclusions, study context, description of theoretical frameworks, use of verification procedures, and reflexivity of account.

For the quantitative studies, 14 items were scored depending on the degree to which the specific criteria were met (“yes” = 2, “partial” = 1, “no” = 0). Items not applicable to a particular study design were marked “n/a” and were excluded from the calculation of the summary score. A summary score was calculated for each paper by summing the total score obtained across relevant items and dividing by the total possible score. Scores for the qualitative studies were calculated in a similar fashion, based on the scoring of ten items. Assigning “n/a” was not permitted for any of the items, and the summary score for each paper was calculated by summing the total score obtained across the ten items and dividing by 20.

2.6. Data Analysis

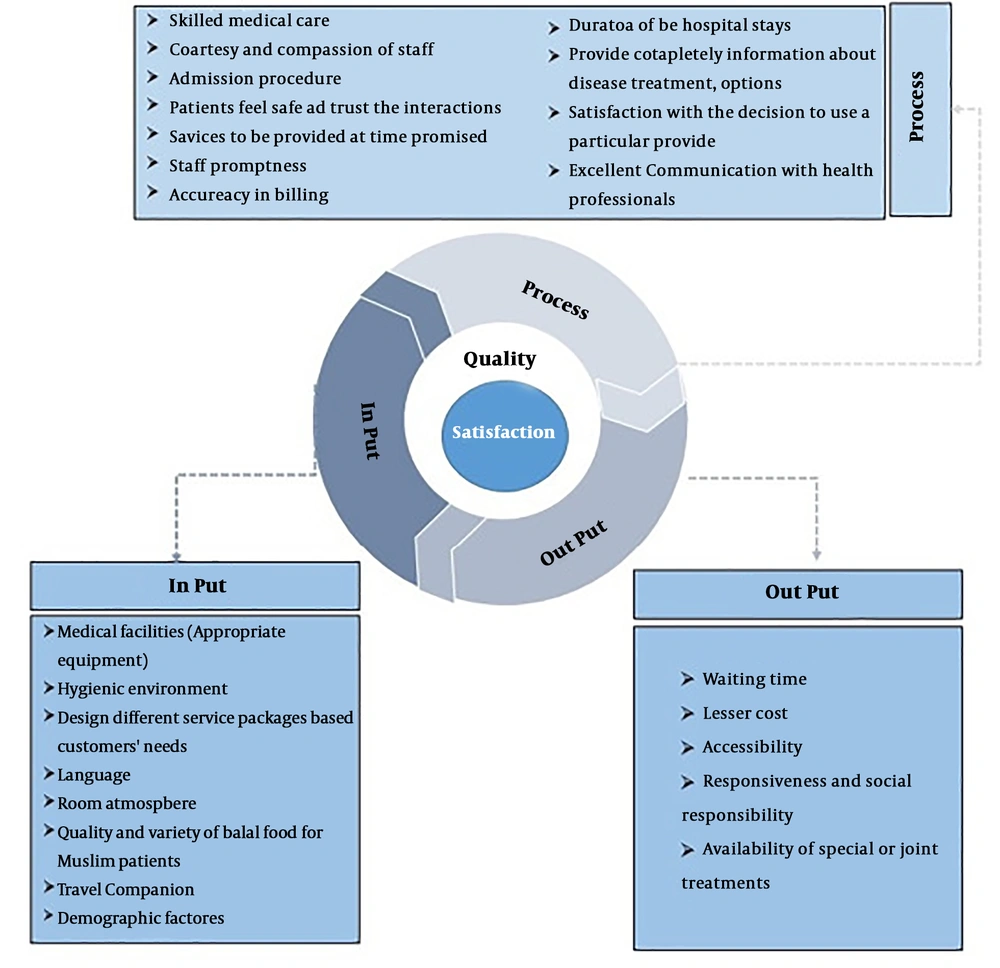

The main aspects for categorizing the factors that affect the satisfaction of medical tourists were determined using the components of the Donabedian model, which is an input-process-output (IPO) model. The model, which was introduced in 1966 with three components (input, process, and output), is used to assess health care systems and health sectors (45, 46). Classification in the Donabedian or IPO model was guided by definitions of input, process, and output specific to this review. That is, input was defined as a factor that provides the resources necessary to meet the needs of medical tourists; process was defined as a factor that contributes to the satisfaction of patients during the course of care and service provision; and output was defined as representing general results that incentivize patients to travel to another country to receive treatment .The specific factorial categories were services, manpower, information, costs, physical conditions, and health equipment. The results of the content analysis were represented in a chart created in Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Search

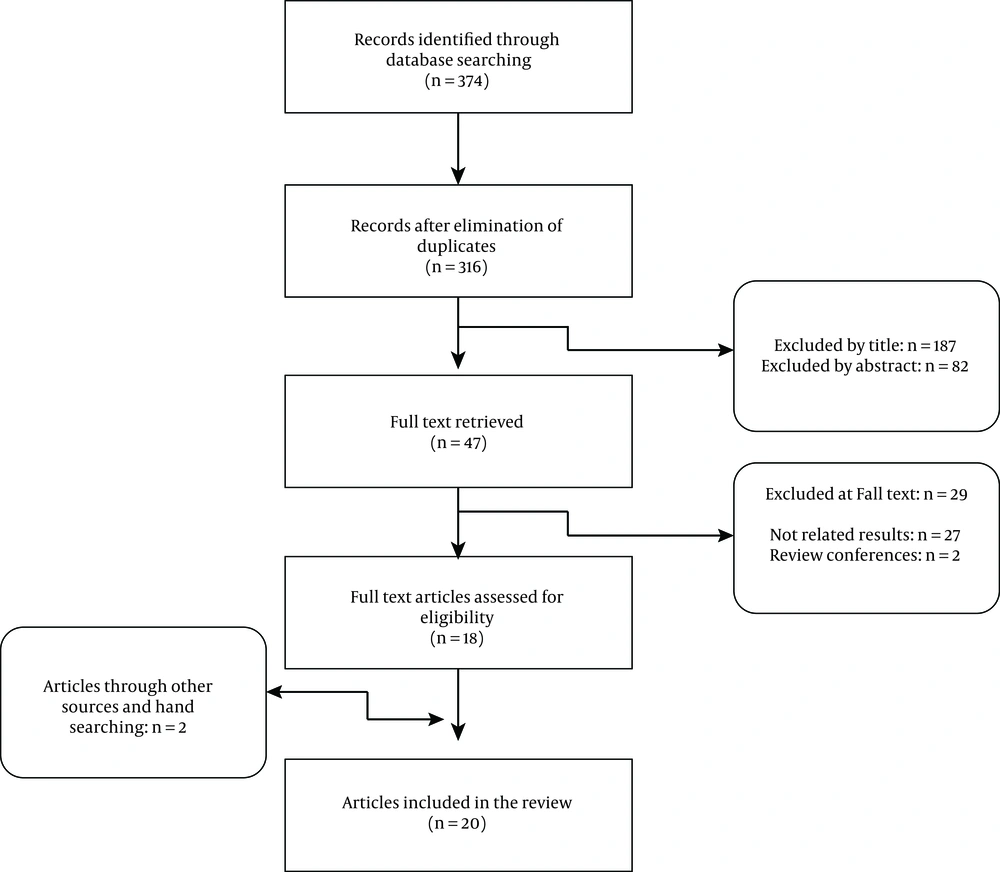

A total of 376 articles were extracted via the database search, and a final sample of 20 studies were selected for the review. Among the final sample, 18 studies were chosen for association with the aim of the systematic review, and two were chosen from the review of the reference lists (Figure 1).

3.2. Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

The studies that were selected on the basis of the inclusion criteria were of quantitative (18 studies), qualitative (one study), and mixed method (one study) designs. Most of them were published between 2008 and 2016 and conducted in Malaysia and India. The quality assessment scores of the articles ranged from 70% to 95%, with 17 of them gaining a score greater than 80%.

3.3. Data Analysis Based on the Systematic Review

A total of 137 influencing factors were identified and organized into six categories. The identified factors were classified on the basis of their relevance in the Donabedian model. That is, the affecting factors on quality can be categorized under these three dimensions and then the quality will lead to satisfaction. We chose this model in this study, because it is widely used and allows researchers and policymakers to identify underlying mechanisms that may lead to poor quality of patient care and subsequently diminishing the satisfaction (Figure 2).

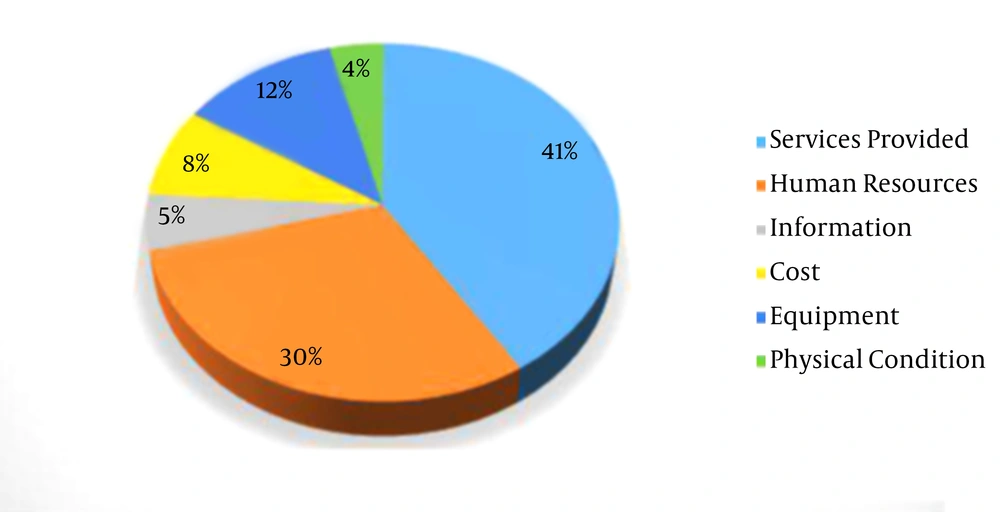

Among the factors identified in the review, 41% are related to the provision of services, 30% are related to the human resources involved in health tourism, 12% are related to the physical conditions of health systems, 8% are associated with costs, 5% are associated with information, and 4% are associated with health equipment (Figure 3).

The factors that were associated with each other and were of the same kind were systematically merged by the research team.

4. Discussion

In the data extraction process, the variation of studies was high, so in the first stage they were not only excluded by examination of the title, they also needed a review of the abstract. In the final stage, a full text review, a significant number of studies were excluded that could not be identified at the earlier stages for deletion. Therefore, the high accuracy required by the authors. The results of the reviewed studies indicated that many factors can affect the satisfaction of medical tourists. These factors include services provided, manpower, health equipment, physical conditions, costs, and information. The review showed that medical tourists regard the factors associated with the provision of services as more influential in their satisfaction than the other identified factors (47, 48). The review indicated that about 90% of the studies used questionnaires and that many of them were performed in Malaysia, India, and Taiwan. According to the results of the studies, service quality and waiting time are among the factors that are directly related to patient satisfaction and indirectly related to customer loyalty (47-50). The influential factors identified by the studies carried out in Malaysia, India, and America were appropriate interaction with staff (10, 51-53) and feelings of safety in interaction with staff (54). The studies conducted in Taiwan and Romania identified feelings of trust from medical tourists as an influencing factor for the satisfaction of patients (54, 55).

Some of the studies identified factors such as courtesy, accountability, and the willingness of employees to help as influential in the satisfaction of medical tourists (36, 56, 57). Courtesy refers to the display of good faith by employees or politeness in the delivery of services, which increases the confidence of medical tourists with regard to a hospital’s ability to enhance their satisfaction. The studies determined whether hospital employees are consistently courteous and respectful and thus regarded such behavior as one of the factors for assessing the quality of health care and one of the determinants of the satisfaction of medical tourists (10, 51). With respect to tourist communication, language factor was indicated as effectively influencing the satisfaction of medical tourists (57, 58). Another factor that affects the satisfaction of medical tourists, relative to their experience in their home countries, is the waiting time for receiving appropriate services. This factor was revealed as an important aspect of ensuring tourist satisfaction in China, India, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Romania, Germany, and Taiwan (10, 52, 59-62). Waiting time is similarly regarded in Canada and the United Kingdom as an essential motivating factor for travel to other countries for treatment (19, 63). The review also showed the cost of health as one of the most important factors for medical tourists’ satisfaction. In America and the UAE, the developed countries, cost disincentives the acquisition of health services and operations, driving citizens to travel to other nations for their health care needs (1). The same consideration of cost as a significant factor was expressed by medical tourists who traveled to India, China, Germany, the UAE, and Jordan (52, 59, 62, 64). Cost was likewise mentioned as a factor that drives tourists from Canada and the United States comes from developed countries, but not of Africa, Gulf countries. the high quality of health care available in developed nations, but what they seek most is quality service at a low cost (65). A combination of low cost and high service quality therefore attracts tourists.

Yet another factor identified in the review was human resources, with the specific aspects being good relationships with medical staff, their clinical skills, the reliability of physicians as evaluated by patients, the education given to medical tourists, the right to select a preferred provider, and the speed of staff (52, 60, 62, 66-69).

Erdogmus and Babic-Banaszak found low satisfaction with factors such as recommendations during discharge, the clarity of instructions, and the duration of counseling with a health care provider (36, 57). This finding contrasts with that of Tam, who reported that medical tourists are satisfied with the provision of clear guidelines by nurses (33).

Given that medical tourists travel to a distant country for health care, discharge is an important aspect of service provision. In particular, medical tourists seek good counseling at the time of discharge. This factor is interrelated with other determinants of satisfaction because the quality of interactions with medical staff increases the trust and confidence of patients in service providers (23, 50).

As indicated in most of the studies that focused on quality, service quality is key to the satisfaction of medical tourists, In both developing countries and developed countries, because other determinants also affect the assessment of service quality by medical tourists. For example, the provision of appropriate recommendations fosters excellent interactions between tourists and providers, thereby inspiring the former to. Other factors that affect tourists’ quality assessments are communication problems caused by language barriers and the preference of medical tourists for quiet environments in hospitals. Therefore, factors such as high waiting times and high costs in high-income countries that have spawned medical tourists to other countries. But the high quality of health care in both high income countries and low incomes has attracted medical tourists. The quality of services directly affects the value perceived by medical tourists, and such perception, in turn, directly influences their satisfaction, which affects their attitudes and behaviors. Satisfaction is positively related to the loyalty of medical tourists and their return to a destination country (23, 50, 55).

5. Conclusions

This review identified services provided, human resources, information, costs, health equipment, and physical conditions as influencing factors for the satisfaction of medical tourists. The most important factor from the perspective of tourists are those related to process of service provision, method of service provision, and behavior of hospital staff. With regard to service provision, the quality of services is of considerable importance for medical tourists. So the quality of services from the viewpoint of medical tourists that the additional explanations have been given about how the other factors understood to affect the quality of services. So the quality of services has a direct impact on the perceived value by medical tourists, what medical tourists perceive has a direct impact on the satisfaction of the clients, and the Satisfaction affects patients’ attitudes and behavior. it has a positive relationship in the loyalty of medical tourists and their return. Note, however, that although these factors were identified as positive factors for destination countries, they can also exert negative effects on the satisfaction of medical tourists in their countries of origin. The results of the review can help policymakers and health professionals in destination countries provide the facilities and conditions necessary for the development of medical tourism.

5.1. Limitations

The review is limited by its focus on studies published in English and Persian. Since the results of this study inferred only from English and Persian language studies then the results should be used cautiously in terms of generalizability.

Other limitations are the impossibility of conducting a meta-analysis and a meta-synthesized analysis of the data. The heterogeneity of studies prevented conducting a meta-analysis for this study. Instead we used an IPO model to summarize the results. This may lessen the power of inferences in comparison with meta-analysis.

.jpg)